Medscape.org provides accredited, ad-free, and evidence-based independent education

Building a Continuum of Care: Case Studies in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

All credits available.

AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™

ANCC Contact Hour(s)

Pharmacists

Knowledge-based ACPE

IPCE 1.00 Interprofessional Continuing Education (IPCE) credit

Target Audience and Goal Statement

This activity is intended for oncologists, obstetricians & gynecologists, pathologists, surgeons, oncology nurses and nurse practitioners (NPs), oncology pharmacists, and other members of the oncology care team.

The goal of this activity is for learners to be better able to select the most optimal anti-HER2 treatments for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer at every stage of care.

Upon completion of this activity, participants will:

- Clinical data associated with emerging anti-HER2 regimens for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer

- Selecting the most optimal anti-HER2 treatment regimens for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer

- Managing adverse events (AEs) that may present with the use of anti-HER2 therapies for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer

- Use the interprofessional team to manage the AEs associated with anti-HER2 therapies for treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer

Disclosures

Medscape, LLC requires every individual in a position to control educational content to disclose all financial relationships with ineligible companies that have occurred within the past 24 months. Ineligible companies are organizations whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients.

All relevant financial relationships for anyone with the ability to control the content of this educational activity are listed below and have been mitigated. Others involved in the planning of this activity have no relevant financial relationships.

Sara A. Hurvitz, MD, FACP

Professor of Medicine Head, Division of Hematology and Oncology Senior Vice President, Clinical Research Division Department of Medicine, UW Medicine Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Seattle, Washington, United States

Joyce A. O’Shaughnessy, MD

Celebrating Women Chair in Breast Cancer Research Baylor University Medical Center Chair, Breast Cancer Committee Breast Cancer Research Program Texas Oncology Sarah Cannon Research Institute Dallas, Texas

Sara M. Tolaney, MD, MPH

Associate Professor of Medicine Harvard Medical School Chief, Division of Breast Oncology Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Boston, Massachusetts

Amy Furedy, RN, OCN

Medical Education Director, Medscape, LLC

Compliance Reviewer/Nurse Planner

Maria morales, msn, rn, clnc.

Associate Director, Accreditation and Compliance, Medscape, LLC

Peer Reviewer

This activity has been peer reviewed and the reviewer has no relevant financial relationships.

Accreditation Statements

In support of improving patient care, Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited with commendation by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

This activity was planned by and for the healthcare team, and learners will receive 1.00 Interprofessional Continuing Education (IPCE) credit for learning and change.

For Physicians

Medscape, LLC designates this live activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™ . Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Contact This Provider

Awarded 1.0 contact hour(s) of nursing continuing professional development for RNs and APNs; 1.00 contact hours are in the area of pharmacology.

For Pharmacists

Medscape designates this continuing education activity for 1.0 contact hour(s) (0.100 CEUs) (Universal Activity Number: JA0007105-0000-23-416-L01-P).

For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider for this CME/CE activity noted above. For technical assistance, contact [email protected] .

Instructions for Participation & Credit

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational activity. For information on applicability and acceptance of continuing education credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

This activity is designed to be completed within the time designated on the title page; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity online during the valid credit period that is noted on the title page. To receive AMA PRA Category 1 Credit ™, you must receive a minimum score of 75% on the post-test.

Follow these steps to earn CME/CE credit*:

- Read about the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

- Study the educational content online or print it out.

- Online, choose the best answer to each test question. To receive a certificate, you must receive a passing score as designated at the top of the test. We encourage you to complete the Activity Evaluation to provide feedback for future programming.

You may now view or print the certificate from your CME/CE Tracker. You may print the certificate, but you cannot alter it. Credits will be tallied in your CME/CE Tracker and archived for 6 years; at any point within this time period, you can print out the tally as well as the certificates from the CME/CE Tracker.

*The credit that you receive is based on your user profile.

Supported by an independent educational grant from Seagen, Inc.

THIS ACTIVITY HAS EXPIRED FOR CREDIT

Medscape Education makes these downloadable slides available solely for non-commercial use by you as a reference tool. You may not use these slides for any commercial purpose or provide these slides to any third party for such party’s use for any commercial purpose. Please refer to the Medscape Terms of Use for additional details.

Activity Transcript

Abbreviations, webmd network.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 November 2020

Clinical Study

A case-control study to evaluate the impact of the breast screening programme on mortality in England

- Roberta Maroni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6420-2881 1 na1 ,

- Nathalie J. Massat ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1095-994X 1 na1 ,

- Dharmishta Parmar 1 ,

- Amanda Dibden ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-9840 1 ,

- Jack Cuzick 1 ,

- Peter D. Sasieni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1509-8744 2 na2 &

- Stephen W. Duffy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4901-7922 1 na2

British Journal of Cancer volume 124 , pages 736–743 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8849 Accesses

18 Citations

79 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Breast cancer

- Cancer screening

Over the past 30 years since the implementation of the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme, improvements in diagnostic techniques and treatments have led to the need for an up-to-date evaluation of its benefit on risk of death from breast cancer. An initial pilot case-control study in London indicated that attending mammography screening led to a mortality reduction of 39%.

Based on the same study protocol, an England-wide study was set up. Women aged 47–89 years who died of primary breast cancer in 2010 or 2011 were selected as cases (8288 cases). When possible, two controls were selected per case (15,202 controls) and were matched by date of birth and screening area.

Conditional logistic regressions showed a 38% reduction in breast cancer mortality after correcting for self-selection bias (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.56–0.69) for women being screened at least once. Secondary analyses by age group, and time between last screen and breast cancer diagnosis were also performed.

Conclusions

According to this England-wide case-control study, mammography screening still plays an important role in lowering the risk of dying from breast cancer. Women aged 65 or over see a stronger and longer lasting benefit of screening compared to younger women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effectiveness of the Korean National Cancer Screening Program in reducing breast cancer mortality

Health benefits and harms of mammography screening in older women (75+ years)—a systematic review

Assessing trends of breast cancer and carcinoma in situ to monitor screening policies in developing settings

Following an evaluation of several randomised controlled trials (RCT) 1 that showed an overall reduction in mortality from breast cancer in women undergoing mammography screening, the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHS BSP) was launched in the United Kingdom (UK) in 1988. At the time, it aimed to offer free routine screening to every woman aged 50–64 once every three years. It now invites women aged 50–70, with an age extension to younger and older women (47–73 years) being trialled. 2

Over the last thirty years, major advances have been made in the fields of cancer screening, treatment, and management (including effective adjuvant systemic therapies 3 and two-view mammography 3 , 4 ), with resulting lengthening of survival times after a breast cancer diagnosis. 5 Despite recent reductions in breast cancer mortality, breast cancer is still the cancer with the highest incidence 6 and the second most common cause of cancer death 7 in females in the UK.

Case-control studies are a useful tool to evaluate screening programmes in settings where lack of equipoise would mean that RCTs would be unethical, or as in this case, where the RCTs have already been done, but there remains a need to ensure that the service is delivering the expected clinical benefit. Case-control studies also overcome some limitations associated with other observational designs by taking into account changes in cancer incidence and use of treatments over time and adjusting for any imbalances in other factors that could affect breast cancer mortality.

Taking as an example a case-control study 8 that resulted in policy change within the NHS cervical screening programme by altering age at first screen and the screening interval, we designed a similar study focussing on the NHS BSP with the aim of:

Evaluating the effect of mammography screening in the NHSBSP on breast cancer mortality

Evaluating the effect of mammography screening on breast cancer incidence, and incidence of late stage disease

Estimating overdiagnosis

Analysing the interplay of early detection, pathology, and treatment on fatality of breast cancer.

The study protocol and results from two pilot studies have been published previously. 9 , 10 , 11 This paper reports on the first objective above (breast cancer mortality), making use of England-wide data. Effects on incidence etc. will be reported in future papers.

Definition of cases and controls

As the main objective was to evaluate the effect of mammography screening on breast cancer mortality, cases were defined as women whose primary cause of death was breast cancer, who were diagnosed at age 47 years or older and died at age 89 years or younger in 2010–2011. We chose the lower limit of 47 as there is a major trial of screening in ages 47–49 ongoing, 2 so substantial numbers of women have been screened in this age group. We chose the upper limit of 89 because above this age we would not expect a major effect of screening taking place mainly at ages 50–70, because we were less confident of the cause of death in the very old, and because screening is essentially aimed at preventing premature mortality, which one might reasonably interpret as death below age 90 years. Only diagnoses occurring after 1990 were included in the analysis. Their matched controls were women sampled from the general population of those invited for screening (99.9% of women eligible for screening in England 12 ) and alive at the time of their corresponding case’s death. Controls may have been diagnosed with breast cancer, but not before their case’s date of diagnosis. Where possible, two controls were selected per case and matched on date of birth (within one month of the case’s) and screening area at date of diagnosis.

For the purposes of the statistical analysis, controls were assigned a date of pseudodiagnosis, equal to the diagnosis date of their corresponding matched case. To be eligible as a case or a control, a woman had to have had at least one invitation to screening prior to the date of diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis.

The primary endpoint was to estimate, among those invited to breast screening, the effect of ever attending breast screening on mortality from breast cancer. Changes in this effect over time were also investigated. Secondary endpoints included the effect of measures of screening intensity, such as time between last screen and diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis, and their estimations in different age subgroups.

Data selection and linkage

Cases were identified from the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) database accessed through the Office for Data Release of Public Health England (PHE). This database contains Office for National Statistics date and cause of death data. NHS Digital used the National Health Application and Infrastructure Services (NHAIS) system to identify matched controls and provided breast and cervical screening histories within.

We excluded any breast screens occurring outside the usual call/recall system of the national screening programme. All the screening histories of the study subjects were considered up to and including their date of diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis.

The data were processed according to the NHS Information Governance guidelines. 13

Sample size

Sample size calculations for the pilot study showed that, assuming an OR for breast cancer mortality of 0.7 and a number of discordant pairs of 33%, two controls per case with 800 breast cancer deaths and 1600 controls would confer more than 90% power to detect such an effect size at the 5% significance level using a two-sided test. 10 As the data for this main phase encompassed the whole of England, we had ample power, not only for the primary outcome (8288 cases and 15,202 controls after exclusions), but also for subgroup analyses.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata version 13 14 by matched (conditional) logistic regression with death from primary breast cancer as the outcome. Date of birth and screening area were accounted for by the matching process.

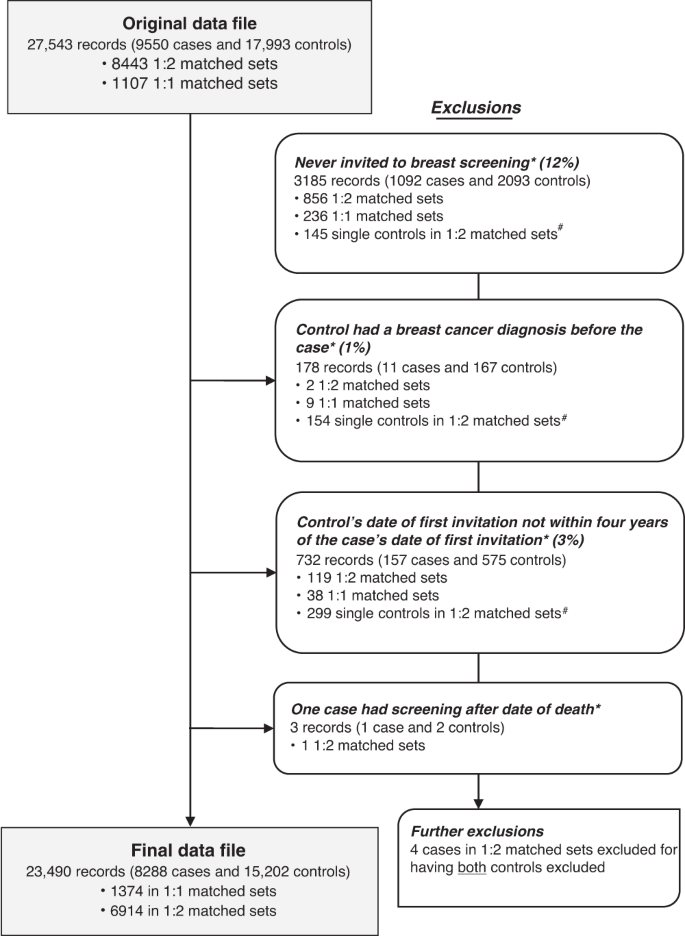

Ineligible subjects were excluded (see Fig. 1 ). For some of these, this resulted in a matched set containing only a case, or only controls, which could then no longer be used in the matched logistic regression. Sensitivity analyses using unmatched logistic regression and controlling for age at diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis and screening area were performed on the same dataset with fewer exclusions; in this case, the inclusion criteria considered were the same, but the fact that a case or a control was excluded did not imply discarding that matched set.

Asterisk indicates that these records were excluded for being in a 1:1 matched set where the case or the control was excluded or for being in a 1:2 matched set where the case or both controls were excluded. Hash indicates that these become 1:1 matched sets in the final dataset. Note: some records may be excluded for more than one reason.

Case-control studies used to evaluate population screening programmes are subject to a type of bias known as non-compliance or self-selection bias, which is based on the assumption that people who are already ill may be less likely to attend screening and those who do attend may be more health conscious, and therefore healthier, than those who do not take up the invitation. This may confer an artificially greater protective effect for screening, which was corrected in our analyses using a variant of the method by Duffy et al. 15

The effect of self-selection bias was estimated using data available on cervical screening attendance for the women in the study, on the basis that any observed protective effect of cervical screening on breast cancer death cannot be due to cervical screening (which does not include breast examination) and is therefore likely to be caused by self-selection bias. In particular, the odds ratio (OR) uncorrected for self-selection is an estimate of the relative risk:

An unbiased estimate of the effect of screening on risk of dying from breast cancer would be (refer to Duffy et al. 15 ):

The OR for death from breast cancer associated with attendance at cervical screening, i.e. the self-selection correction factor, can be considered an approximate estimate of the relative risk:

Therefore, we obtain an estimate of θ by dividing γ by φ . The fundamental assumption here is that the populations choosing to attend or not to attend cervical cancer screening have the same risk of dying of breast cancer a priori as those choosing or not choosing to attend breast cancer screening. We do not assume that the effects of self-selection are the same in the two programmes. This is referred to as our first method of correction in the Results section.

As there is considerable uncertainty in the extent of self-selection, and of course decisions to attend at two separate screening programmes are likely to be confounded with each other, we also corrected for this using the method of Duffy et al. 15 . This method estimates the effect of participation in screening in those who would participate if invited as:

where p is the proportion of the invited population who participate in screening and D r is the a priori relative risk of dying of breast cancer for someone who chooses not to attend compared to an uninvited general population member. We estimated D r as 1.19 (95% CI 1.11–1.27), from the cohort study of Johns et al. 16 Thus, this correction was based on a prospective estimate of the extent of self-selection bias in a cohort of 988,090 women in the NHS Breast Screening Programme. We estimated p as 73.4% from the annual report of the National Programme. 12 This method, referred to as our second method of correction in the Results section, also yields an estimate of the effect of invitation to screening as follows: 15

More details on the methods are available in the published study protocol 9 and pilot study analysis. 10

The study dataset had a total of 9550 cases and 17,993 controls. There were 1107 sets with matching ratio 1:1 (1 case to 1 control) and 8443 sets with matching ratio 1:2 (1 case to 2 controls). Records of 1262 cases and 2791 controls (15% of the total) were excluded for various reasons before the statistical analysis (see study flow diagram in Fig. 1 ). This left a final dataset of 8288 cases and 15,202 controls, divided into 1,374 matched sets of size 1:1 and 6914 of size 1:2.

Sensitivity analyses using unconditional logistic regression were performed including subjects without a matched case or control, leaving us with 8479 cases and 16,794 controls.

Table 1 shows patient demographics and screening histories. Median age at first diagnosis was 64 years for both cases and controls and median age at death for cases was 71 years. Whilst the distributions of the number of screening invitations in the two study groups were comparable, differences can be noted in screening attendance, with 72% of the cases versus 82% of the controls attending their first screening invitation; 64% of the cases versus 76% of the controls attending their last screening invitation before diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis; and 21% of the cases versus 12% of the controls never being screened. Median time between last screen and date of diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis for compliers was also slightly longer for cases. From the data available on cervical screening history up to the date of diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis, it can be noted that 22% of the cases compared with 19% of the controls never had a cervical screen.

Table 2 summarises the main results without and with correction for self-selection bias. Using data from cervical screening attendance, the self-selection correction factor was estimated to be 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.84). The primary endpoint, the association between attending one or more screens and death from breast cancer, had a resulting OR = 0.49 (95% CI 0.45–0.53) and, when corrected for self-selection, had OR = 0.62 (95% CI 0.56–0.69) by our first method and OR = 0.63 (95% CI 0.55–0.71) by our second. Using the second method, the estimate of the effect of invitation to screening was a 26% reduction in breast cancer mortality (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.68-0.81). The unmatched logistic regression on the larger dataset for sensitivity analyses showed a similar effect of screening on breast cancer mortality both before and after controlling for age at diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis and screening area (in both cases, uncorrected OR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.51–0.59).

In order to analyse changes of the effect of screening over time, we excluded women diagnosed before year 2000 (13% of the total records), which led to a corrected OR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.51–0.63) for the effect of ever attending mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality. Women diagnosed from year 2003 onwards had an even larger benefit from being screened (OR corrected by first method = 0.53, 95% CI 0.47–0.59). The estimated effect continued to increase as we restricted the year of diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis further in time (Supplementary Fig. 1 ).

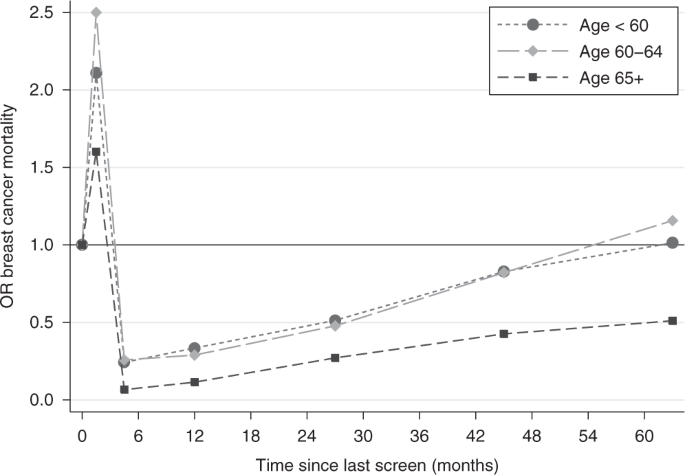

Table 3 shows how the effect of screening varies depending on how much time has passed between a woman’s last screen and her diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis. Screen-detected cancers (assumed to be cancers diagnosed within three months of screening) showed a positive association with breast cancer fatality, after self-selection bias correction by our first method (OR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.68–2.22), while women screened in any other time interval were at reduced risk of dying from breast cancer. This was lowest for women screened in the last year (OR corrected by our first method = 0.19, 95% CI 0.17–0.23) and gradually increased, while still conferring a beneficial effect to screening, for women screened further back in time with respect to their date of diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis. Results using our alternative correction for self-selection were very similar (Table 3 ). Note that the time is from screening to diagnosis, not to death. The Table shows risk of subsequently dying of breast cancer increasing by the time between the screen and diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis.

A similar analysis is shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2 for different time intervals after stratifying for three different age categories at diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis (younger than 60 years, between 60 and 64 years, and 65 years or older). The results show that the protective effect of a screen is greater and lasts longer in the oldest group. The benefit of attending screening in the three years prior to diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis, the recommended interval for screening in the NHS BSP, is shown in the final row of Table 4 , and shows close to a halving of risk with screening within the recommended interval, following self-selection correction by our first method (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.46–0.57). Results using our second method of correction were very similar to those using the first (Supplementary Table 1 ). The estimated effect of invitation to screening within the last 36 months using our second method was a 33% reduction in breast cancer mortality (OR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.61–0.73).

Note: the coordinates on the x -axis are the midpoints of the time intervals: 0–3, 3–6, 6–18, 18–36, 36–54 and 54–72 months.

Despite the many improvements in treatments, diagnostic procedures and technologies over the last thirty years, and changes in baseline rate of breast cancer mortality, our data showed an overall reduction in the risk of dying from breast cancer of ~38% for women attending at least one mammography screen, after adjusting for self-selection bias. This is in line with the results obtained from the pilot phase of the study, 10 in which a mortality reduction of 39% was seen for women attending screening in London (deaths occurring in 2008–2009). Using the same calculation method as in the review by the Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening UK Independent Review, 17 this would correspond to approximately nine breast cancer deaths prevented for every 1,000 women attending screening at ages 50–69 years, larger than but in the same general scale as the six deaths estimated from the UK Independent review.

It should be noted that there is a wide range of estimates of the absolute mortality benefit of mammography screening 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 some finding considerably smaller benefits than above. The size of the estimated effect depends on sources used and assumptions made. However, it has been shown to depend more crucially on whether the effect pertains to screening per se or to invitation to screening only, and on the timescale envisaged. 22 Screening prevents deaths not this year or next, but 5, 10, 15 or 20 years from now. Considering the effect of screening on 10-year mortality will considerably underestimate the absolute benefit. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that while the body of evidence, randomised and observational, points to a substantial reduction in breast cancer mortality with screening, there is sufficient variation that different views are still possible.

Our first method of correction for self-selection caused a decrease of about 25% in the estimated protective effect of screening for women having at least one mammogram. The second method yielded similar results. This is a greater correction than the one estimated in the pilot phase, 10 where self-selection only played a minor role, despite the fact that the final risk reduction is very similar. London has a lower coverage than the rest of England for both breast and cervical screening, which is largely explained by factors like deprivation and ethnicity. 23 Such variations in coverage might be one of the causes for the different impact of self-selection between the two phases of the study. For example, a larger population of non-participants, such as in London, may be less different in health status than a smaller population. In the Swedish two-County trial, 24 where only 15% of the population were non-participants, the rate of death from breast cancer in this population was very high. It is also worth noting that, during the early 21st century, breast screening attendance was rapidly increasing in London, and the socioeconomic gradient in attendance was reducing with time nationally. 25 , 26

Case-control studies tend to give higher estimates of benefit than other evaluations, largely because they assess the effect of actually being screened rather than simply being invited to screening. 19 , 27 It should be noted that with our second correction for self-selection bias, we were able to estimate the effect of invitation, giving a 26% breast cancer mortality reduction, similar to the effect observed in the randomised trials in this age group and to the prospectively estimated effect of a 25% reduction in the Copenhagen screening programme. 28 As a comparison, in the review by the Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening, 17 a meta-analysis of 11 RCTs found that the relative risk reduction of breast cancer mortality for women invited to screening was 20%. Furthermore, in the same report, the panel stated that the case-control studies that they had analysed seemed to inflate the benefit of screening compared to the trials and postulated that this may have been caused by some residual bias unaccounted for by the authors. We believe that our adjustments for self-selection bias has largely accounted for this and that the greater effect of screening in this study is due to technical improvements in mammography since the RCTs were carried out, accompanied by improved treatment and strong quality assurance measures in the NHS BSP. 11

The greater benefit of screening observed for women diagnosed after year 2000 was similar to the pilot study, 10 but here we were able to restrict the analysis to later years of diagnosis and see the benefit getting larger (data not shown). We could conjecture that this improvement was due to the introduction of better procedures in the NHS BSP, such as two-view mammography at every attendance in year 2000 4 ; however, there may be a bias in comparing different times since diagnosis as we only have data on deaths in years 2010–2011. In the first place, cases diagnosed before 2000 have a long survival by definition, and there might therefore be an over-representation of screen-detected cancers. In other words, it is more likely that a case diagnosed before year 2000, for example, who had a breast cancer for more than 10–11 years before dying from it, had a screen-detected cancer rather than a symptomatic one. This confers a bias against screening in the analysis of cancers diagnosed prior to the year 2000. In the second place, there will be a bias in favour of screening if the analysis is restricted to cancers diagnosed within a short time before death, i.e. if we only consider women (pseudo)diagnosed a few years before 2010–2011. We are therefore unable to make any definitive conclusions on the impact of any improvements in the NHS BSP over time.

As shown in RCTs of breast screening, 24 measures of the benefit of screening are largely influenced by the consequent reduction in mortality from symptomatic cancers. This is due to the fact that screen-detected cancers (defined as the ones diagnosed within three months of a screen), despite being less fatal overall, represent a larger proportion of the cancer-related deaths in the immediate period after a screen as it can be seen from the spike in excess mortality in Fig. 2 .

The duration of the benefit of attending screening appears to be greater in older women (Table 4 and Fig. 2 ). Women aged 65 or more see the greatest and longer lasting benefit, which might suggest that they could be screened less often than younger women. This result is in agreement with the impact of ageing on breast cancer biology 29 and is also potentially important in light of the recent incident in the NHS BSP, where a number of women aged 69 and 70 years did not receive the scheduled invitation to their last screening appointment. 30 The exact number affected has been debated but an Independent Review concluded that 5000 women were not invited as scheduled, and that a further 62,000 could be interpreted as having missed their final invitation as defined in the service specification. 30 Our findings suggest that the effect of a delayed screen in older women has a lesser consequence for increased risk of breast cancer mortality than it would have had in younger women. While three years is a longer interval than other programmes in Europe and North America, and further slippage of the interval should be avoided if at all possible, these results could also be used as guidelines for screening units at times of capacity constraints, with the provision that all women receive an opportunity for a final screen around or shortly after age 70. There is interest in stratified screening and these results may inform further thinking on this subject.

A limitation of the study is the retrospective design and the potential for self-selection bias. We have corrected for this in two different ways and for one of these, an effect of invitation to screening was derived which was consistent with trials results and prospective studies for this age group. However, it must be acknowledged that there remains some uncertainty about the extent of self-selection bias. Furthermore, case-control studies for cancer screening programmes are subject to an inherent type of anti-screening bias known as screening opportunity bias. 27 As most of the controls do not have a breast cancer diagnosis, the only way they can be exposed to screening is if they attended a mammography appointment in the past. Cases, on the other hand, may have had a screen in the past, but some of them will also have an additional screen for when their cancer was diagnosed. This induces an artificially higher retrospective probability of screening exposure among cases. Screening opportunity bias was corrected for in the pilot study, 10 where a 10–15% increase in mortality reduction was seen following this, but here we preferred to keep a conservative approach and not adjust for it. To minimise biases with respect to age and opportunity to be screened, we matched very closely for age. This meant that in 1107 cases out of 9550, we could only find one control.

Although the effect of the NHS BSP in preventing breast cancer mortality has been assessed several times, 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 we are aware of only one other case-control study conducted using national data. 34 The latter relies on data up to year 2005 (diagnoses and deaths took place between 1991 and 2005), while ours uses more recent data up to year 2012, arguably more in the epoch of effective adjuvant systemic therapies. It is of interest that our more recent case base shows similar results in terms of the reduction in risk of breast cancer death with screening. In any case, we suggest that it would be of interest to repeat this type of analysis for years thereafter, to ensure that the programme continues to deliver its aims even with the introduction of new diagnostic technologies (e.g. digital mammography). Before the establishment of the NHS BSP in 1987, it was suggested that a routine case-control assessment could and should be part of an ongoing evaluation of a mass screening programme. 35 For this reason, we believe that this exercise should be held on a two-yearly basis.

The results of further national case-control studies (1) evaluating the effect of the NHS BSP on breast cancer incidence and incidence of late stage disease, (2) estimating overdiagnosis, and (3) analysing the interplay of early detection, pathology and treatment on fatality of breast cancer will be published shortly.

To conclude, this study showed that the breast screening programme in England continues to play an important role in the control of breast cancer. The effect of screening within the NHS BSP in England is stronger and longer lasting in women aged 65 or over, but it remains highly relevant for younger women.

Forrest, A. P. M. Breast cancer screening: report to the Health Ministers of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland by a working group . (HM Stationery Office, London, 1987)

Moser, K., Sellars, S., Wheaton, M., Cooke, J., Duncan, A., Maxwell, A. et al. Extending the age range for breast screening in England: pilot study to assess the feasibility and acceptability of randomization. J. Med. Screen 18 , 96–102 (2011).

Article Google Scholar

Plevritis, S. K., Munoz, D., Kurian, A. W., Stout, N. K., Alagoz, O., Near, A. M. et al. Association of screening and treatment with breast cancer mortality by molecular subtype in US Women, 2000-2012. Jama 319 , 154–164 (2018).

Patnick, J. NHS breast screening: the progression from one to two views. J. Med Screen 11 , 55–56 (2004).

Cancer Research UK. Breast cancer survival trends over time. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/survival#heading-Two (2014).

Cancer Research UK. Cancer incidence for common cancers. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence/common-cancers-compared#heading-Two (2020).

Cancer Research UK. Cancer mortality for common cancers. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/mortality/common-cancers-compared#heading-Two (2019).

Sasieni, P., Adams, J. & Cuzick, J. Benefit of cervical screening at different ages: evidence from the UK audit of screening histories. Br. J. Cancer 89 , 88–93 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Massat, N. J., Sasieni, P. D., Parmar, D. & Duffy, S. W. An ongoing case-control study to evaluate the NHS breast screening programme. BMC Cancer 13 , 596 (2013).

Massat, N. J., Dibden, A., Parmar, D., Cuzick, J., Sasieni, P. D. & Duffy, S. W. Impact of screening on breast cancer mortality: The UK Program 20 Years On. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 25 , 455–462 (2016).

Massat, N. J., Sasieni, P. D., Tataru, D., Parmar, D., Cuzick, J. & Duffy, S. W. Explaining the better prognosis of screening-exposed breast cancers: influence of tumor characteristics and treatment. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 25 , 479–487 (2016).

The NHS Information Centre. Breast Screening Programme, England 2010-11. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub05xxx/pub05244/bres-scre-prog-eng-2010-11-rep.pdf (2012).

Department of Health. Information Governance Toolkit. https://www.igt.hscic.gov.uk (2020).

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. (College Station, 2013).

Duffy, S. W., Cuzick, J., Tabar, L., Vitak, B., Chen, T. H.-H., Yen, M.-F. et al. Correcting for non-compliance bias in case–control studies to evaluate cancer screening programmes. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. 51 , 235–243 (2002).

Johns, L. E., Coleman, D. A., Swerdlow, A. J. & Moss, S. M. Effect of population breast screening on breast cancer mortality to 2005 in England and Wales: an individidual-level cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 116 , 246–252 (2017).

Independent, U. K. Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet 380 , 1778–1786 (2012).

Gøtzsche, P. C., Jørgensen, K. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. 6 , CD001877 (2013).

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Breast Cancer Screening , Vol. 15. (IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, 2016).

Dimitrova, N., Parkinson, Z. S., Bramesfeld, A., Ulutürk, A., Bocchi, G., López-Alcalde, J. et al. European Guidelines for Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis–the European Breast Guidelines . Joint Research Centre Technical Reports (Luxembourg Publications Office of the European Union, 2016).

Siu, A. L. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann. Intern Med. 164 , 279–296 (2016).

Duffy, S. W., Chen, T. H.-H., Smith, R. A., Yen, A. M.-F. & Tabar, L. Real and artificial controversies in breast cancer screening. Breast Cancer Manag. 2 , 519–528 (2013).

Massat, N. J., Douglas, E., Waller, J., Wardle, J. & Duffy, S. W. Variation in cervical and breast cancer screening coverage in England: a cross-sectional analysis to characterise districts with atypical behaviour. BMJ Open 5 , e007735 (2015).

Tabar, L., Fagerberg, G., Duffy, S. W., Day, N. E., Gad, A. & Grontoft, O. Update of the Swedish two-county program of mammographic screening for breast cancer. Radio. Clin. North Am. 30 , 187–210 (1992).

CAS Google Scholar

Eilbert, K. W., Carroll, K., Peach, J., Khatoon, S., Basnett, I. & McCulloch, N. Approaches to improving breast screening uptake: evidence and experience from Tower Hamlets. Br. J. Cancer 101 , S64–S67 (2009).

Douglas, E., Waller, J., Duffy, S. W. & Wardle, J. Socioeconomic inequalities in breast and cervical screening coverage in England: are we closing the gap? J. Med. Screen 23 , 98–103 (2016).

Walter, S. D. Mammographic screening: case-control studies. Ann. Oncol. 14 , 1190–1192 (2003).

Olsen, A. H., Njor, S. H., Vejborg, I., Schwartz, W., Dalgaard, P., Jensen, M.-B. et al. Breast cancer mortality in Copenhagen after introduction of mammography screening: cohort study. BMJ 330 , 220 (2005).

Benz, C. C. Impact of aging on the biology of breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 66 , 65–74 (2008).

The Independent Breast Screening Review 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/764413/independent-breast-screening-review-report.pdf (2018).

Moss, S. M., Summerley, M. E., Thomas, B. T., Ellman, R. & Chamberlain, J. O. A case-control evaluation of the effect of breast cancer screening in the United Kingdom trial of early detection of breast cancer. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 46 , 362–364 (1992).

Allgood, P. C., Warwick, J., Warren, R. M., Day, N. E. & Duffy, S. W. A case-control study of the impact of the East Anglian breast screening programme on breast cancer mortality. Br. J. Cancer 98 , 206–209 (2008).

van der Waal, D., Broeders, M. J., Verbeek, A. L., Duffy, S. W. & Moss, S. M. Case-control studies on the effectiveness of breast cancer screening: insights from the UK Age Trial. Epidemiology 26 , 590–596 (2015).

Johns, L. E., Swerdlow, A. J. & Moss, S. M. Effect of population breast screening on breast cancer mortality to 2005 in England and Wales: a nested case-control study within a cohort of one million women. J. Med. Screen 25 , 76–81 (2018).

Sasco, A. J., Day, N. E. & Walter, S. D. Case-control studies for the evaluation of screening. J. Chronic Dis. 39 , 399–405 (1986).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Data for this study is based on information collected and quality assured by the PHE National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. Access to the data was facilitated by the PHE Office for Data Release. We would like to thank Rachael Brannan from the PHE Office for Data Release and David Graham from NHS Digital for their help with the data selection and matching of cases and controls. This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Roberta Maroni, Nathalie J Massat

These authors jointly supervised this work: Peter D Sasieni, Stephen W Duffy

Authors and Affiliations

Centre for Cancer Prevention, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London, EC1M 6BQ, UK

Roberta Maroni, Nathalie J. Massat, Dharmishta Parmar, Amanda Dibden, Jack Cuzick & Stephen W. Duffy

Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, Cancer Prevention Group, School of Cancer and Pharmaceutical Sciences, King’s College London, Guy’s Campus, Great Maze Pond, London, SE1 9RT, UK

- Peter D. Sasieni

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

R.M. oversaw the first draft of the manuscript draft and submission. N.J.M., J.C., P.D.S. and S.W.D. designed the study. D.P. contributed to data collection and cleaning. A.D. assisted with data interpretation. R.M. and S.W.D. analysed the data and produced the figures. All the authors critically reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stephen W. Duffy .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Department of Health. Ethical approval was obtained from the London Research Ethics Committee of the National Research Ethics Service (reference: 12/LO/1041), and by the National Information Governance Board Ethics and Confidentiality Committee (reference: ECC 6–05 (e)/2012). The ethics committee agreed that informed consent to participate for the study subjects was not necessary. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

Data were saved on the servers of the Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, in a folder with restricted access to D.P. A clean, anonymised version of the data was produced and made available to R.M., A.D. and S.W.D. with restricted access to the staff of the Policy Research Unit in Cancer Awareness, Screening and Early Diagnosis at Queen Mary University of London. The data were obtained via the Office for Data Release at Public Health England. We do not have authority to share the data with others, but requests for access to data will be forwarded to the Office for Data Release.

Competing interests

P.D.S. reports personal fees from GRAIL Bio outside the submitted work. J.C. and S.W.D. are members of the editorial board of the British Journal of Cancer. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

his research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme, conducted through the Policy Research Unit (PRU) in Cancer Awareness, Screening and Early Diagnosis, PR-PRU-1217-21601. The PRU is a collaboration between researchers from seven institutions (Queen Mary University of London, University College London, King’s College London, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Hull York Medical School, Durham University, and Peninsula Medical School). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funding body was not involved in design, data collection, analysis or interpretation. The funding body had sight of the paper prior to publication but has not had input to its content.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary materials, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maroni, R., Massat, N.J., Parmar, D. et al. A case-control study to evaluate the impact of the breast screening programme on mortality in England. Br J Cancer 124 , 736–743 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01163-2

Download citation

Received : 18 March 2020

Revised : 21 October 2020

Accepted : 28 October 2020

Published : 23 November 2020

Issue Date : 16 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01163-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Screening for atrial fibrillation: risks, benefits, and implications on future clinical practice.

- Muhammad Haris Ilyas

- Amaan Mohammad Sharih

- Syeda Anum Zahra

Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine (2024)

Artificial intelligence in the treatment of cancer: Changing patterns, constraints, and prospects

- Mohammad Ali

- Shahid Ud Din Wani

- Seema Mehdi

Health and Technology (2024)

Educational Initiatives to Improve the Cancer-Related Disparities Facing Transgender and Gender Diverse (TGD) Individuals

- Elizabeth Cathcart-Rake

- Aminah Jatoi

Journal of Cancer Education (2024)

Years of life lost due to cancer in the United Kingdom from 1988 to 2017

- Amar S. Ahmad

- Judith Offman

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Case report of long-term survival with metastatic triple-negative breast carcinoma

Treatment possibilities for metastatic disease.

Editor(s): NA.,

Lifespring Cancer Treatment Center, Seattle, WA.

∗Correspondence: Bryce Douglas La Course, Lifespring Cancer Treatment Center, 510A Rainier Avenue South, Seattle, WA (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Abbreviations: ALL = acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CA = cancer antigen, CT = computed tomography, DC = dendritic cell, ER = estrogen receptor, GM-CSF = granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor, HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, MTD = maximum tolerated dose, PET = positron emission tomography, PR = progesterone receptor, TNBC = triple-negative breast cancer, Tregs = regulatory T cells.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in the study for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Rationale:

Breast cancer is the most common as well as one of the most devastating cancers among women in the United States. Prognosis is poor for patients with metastatic breast cancer, especially for patients with so-called “triple-negative” disease. The lack of effective therapies for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer outlines the need for novel and innovative treatment strategies.

Patient concerns:

A 58-year-old underwent a mastectomy which revealed a recurrent triple-negative breast carcinoma. Afterward, she presented with a growing mass in her left axilla and chest wall. A computed tomography scan showed axillary and supraclavicular adenopathy, nodules in the left upper and lower lobe of the lungs, and 2 areas of disease in the liver. A bone scan showed lesions in the ribs.

Diagnosis:

The patient was diagnosed with a recurrent metastatic triple-negative breast carcinoma that spread to the lung, liver, and bones.

Interventions:

The patient was treated with metronomic chemotherapy, sequential chemotherapy regimens, and immunotherapy.

Outcomes:

The patient is now over 15 years out from her diagnosis of metastatic disease without any evidence of recurrent disease, likely due to the patient's treatment strategy which included sequential metronomic chemotherapy regimens and immunotherapy.

Lessons:

Sequential metronomic chemotherapy regimens in combination with immunotherapy might be an effective treatment option for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. We hope that this case can provide some guidance for the treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and motivate research that can potentially lead to more cases of long-term survival for patients who develop this dismal disease.

1 Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most common cancer diagnosed among women in the United States and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with approximately 41,000 patients projected to die from this disease in 2018 alone. [1] The prognosis for patients with metastatic breast cancer varies based on many factors including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status. Tumors that do not express the ER, PR, or HER2 receptors are known as “triple-negative” breast cancers (TNBCs) and represent approximately 11% of all breast cancers. [2] This subtype of breast cancer is known for being aggressive, having a high probability of distant recurrence after adjuvant therapy, and progressing quickly on palliative chemotherapy treatment in the metastatic setting. [2,3] Patients with metastatic TNBC have a poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of 13.3 months with treatment. [3] Continuing chemotherapy treatment until disease progression is currently the standard of care for patients with metastatic TNBC, with no preferred chemotherapy regimens established at this time. The lack of effective therapies for this aggressive disease highlights the need for the development of novel treatment strategies. Here we report the case of a patient with metastatic TNBC that metastasized to the lungs, liver, and bones who achieved long-term remission without evidence of disease recurrence after 15 years. Her case is followed by a discussion of the treatment strategy which likely has led to her remarkable survival.

2 Case report

A Caucasian female initially presented with a nodule in her left breast in March 2001 at the age of 56. Before this, the patient was a homemaker with a relatively unremarkable past medical history aside from some mild arthritis. Her father and brother had prostate cancer, and her mother apparently had uterine cancer. Her social history was negative for tobacco, alcohol as well as illicit drug use. A core biopsy performed in mid-April 2001 showed a high-grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma, with a Bloom–Richardson score of 9/9. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor was positive for ER expression and negative for PR expression and HER2 overexpression. The patient underwent a left lumpectomy with an axillary lymph node dissection shortly after the biopsy. Pathology revealed a 2.0 × 1.8 × 1.3 cm high-grade invasive ductal carcinoma. 0 of the 15 left axillary lymph nodes examined were positive for carcinoma, and no lymphatic invasion was identified. The patient declined adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

In the spring of 2003, the patient noticed another mass under the nipple of her left breast. An ultrasound-guided left breast biopsy was performed in early May 2003 which revealed a high-grade ductal carcinoma. The patient then underwent bilateral simple mastectomies to remove the left breast tumor in late May 2003. Pathology of the left breast mass showed a poorly-differentiated carcinoma that measured 3.0 × 3.5 × 2.0 cm with a Bloom–Richardson score of 9/9. The tumor was negative for ER, PR, HER2 by immunohistochemistry, and for amplification of the HER2 gene by fluorescence in situ hybridization, indicating she had triple-negative recurrent disease ( Fig. 1 ). The patient again declined any treatment.

In early September 2003, the patient noticed a growing mass in her left axilla and chest wall. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed a 3.8 cm necrotic left axillary lymph node with axillary and supraclavicular adenopathy. Nodules were also seen in the left upper and lower lobe of the lungs along with 2 subtle areas of low attenuation in the liver. A bone scan performed in December 2003 revealed bone lesions along the left 3rd and 6th ribs posterolaterally. The patient was concluded to have metastatic disease to the lungs, liver, and bones. Unfortunately, these images have been destroyed by the imaging facility and cannot be used in this publication. The details of the scans were obtained from the official written scan reports.

After consulting with the patient, she decided to proceed with chemotherapy treatment. She was given 4 sequential chemotherapy regimens ( Table 1 ) to try and control her cancer along with monthly zoledronic acid to try to prevent bone complications due to her osseous metastases. Granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was used throughout the treatment to prevent or treat chemotherapy-induced neutropenia as well as stimulate the immune system. After 14 doses of weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin, there was remarkable tumor shrinkage in the left chest wall and axillary area on her physical examinations. Her cancer antigen (CA) 27.29 (normal range: <38 U/mL) also decreased from a pretreatment level of 52.1 to 19.8 in mid-April 2004 which was consistent with the patient's physical exam findings. The patient's CA 27.29 then remained within normal range from this point onward. The patient was then switched to weekly doxorubicin liposome in June 2004. Twelve doses were planned, but she only received 8 doses due to developing palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia. Her symptoms resolved after the drug was withdrawn in late July 2004. The patient then continued chemotherapy treatment and received 6 doses of weekly gemcitabine and cisplatin from August 2004 to October 2004. The patient developed thrombocytopenia and her second to the last dose of this regimen was given with a reduced dose of cisplatin. Gemcitabine was dose reduced during her last infusion of this regimen. She was then switched to weekly vinorelbine in early December 2004 and completed 12 doses of chemotherapy treatment in late February 2005.

Aside from developing neutropenia and thrombocytopenia secondary to chemotherapy treatment and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia secondary to doxorubicin liposome, the patient tolerated her treatment relatively well. A CT scan performed in March 2005 showed no evidence of disease in the lung and liver. The patient was taken off of chemotherapy treatment but continued on monthly zoledronic acid and pursued a watchful waiting approach from February 2005 to June 2005.

In June 2005 the patient developed several small skin nodules in her left axillary chest wall. A positron emission tomography (PET) and CT scan performed shortly after showed minimal thickening of the left chest wall, suspicious for recurrent disease, although no biopsy was performed. There was no other evidence of metastatic disease. She was started on imiquimod cream, which was applied on the skin nodules, for immune stimulation. The patient reported pruritus and erythema in the applied area, but she did not complain of having any pain. These nodules resolved after a few weeks. In October 2005, the patient noticed several pea-sized nodules in her left axilla which were also suspicious for disease recurrence. The patient continued applying imiquimod cream to the area. She developed erythema, ulceration, and skin breakdown in that area, but this resolved after stopping imiquimod. The skin nodules resolved by January 2006. The patient's condition continued to improve, and the frequency of her zoledronic acid infusions was reduced to every other month in May 2006, and then quarterly in September 2007. In December 2008 she continued with biannual infusions of zoledronic acid. A germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 analysis performed in December 2009 did not detect any mutations. Routine PET/CT and CT scans continue to show no evidence of recurrent or persistent metastatic disease. The patient is now 73 years old and is enjoying a good quality of life. She is currently over 15 years out from her diagnosis of recurrent metastatic TNBC.

3 Discussion

The prognosis of this patient before starting treatment was particularly poor, not only because her tumor did not express the ER, PR, or HER2 receptors, but also because she had stage IV disease with multiple visceral metastases. With the typical prognosis of metastatic TNBC being slightly over 1 year, the 15-year survival of this patient is quite remarkable, especially given that she is currently free of disease and has not received any chemotherapy treatment since late February 2005. To our knowledge, this patient is the longest reported survivor of metastatic TNBC. Her long-term survival without recurrence suggests that this patient may be cured of a cancer that is not thought to be curable. We believe that our treatment methodology, which included using metronomic chemotherapy, switching chemotherapy regimens before anticipated disease progression, and utilizing immune therapies, all contributed to her outstanding survival. Below, we will describe each of these treatment strategies in detail.

3.1 Metronomic chemotherapy

The dosing of a standard chemotherapy regimen is based on a maximum tolerated dose (MTD). This dose is typically the highest possible dose that is not lethal to the patient. The idea of an MTD was originally developed with the logic that “more is better” to try and maximize the amount of cancer cell death. A high dose of chemotherapy can kill cancer cells, but due to the relatively nonspecific mechanism of action of most chemotherapy agents, this high dose of chemotherapy can also result in clinical toxicities which is why standard chemotherapy regimens are often administered every 3 weeks. The breaks in between standard chemotherapy doses are crucial for the recovery of normal tissues, but logically this can also give time for cancer cells to grow and progress as well. Thus, the dosing of chemotherapy agents and the frequency of chemotherapy administration may play an important role in the efficacy of treatment as well as the patient's quality of life.

This patient received lower doses of chemotherapy on a more frequent basis, also known as “metronomic chemotherapy.” Although lower doses of chemotherapy agents were given to this patient during each administration, the overall dose intensity (the total dose of chemotherapy administered per unit time) of her chemotherapy agents was a similar, if not higher, dose intensity, compared to the standard dosing of each respective chemotherapy agent. Studies have shown that reducing dose intensity, most commonly due to myelosuppression, correlates with poorer disease-free survival and overall survival, while maintaining a relatively high planned dose intensity is associated with better clinical outcomes. [4] Due to the lower doses used during each administration, metronomic chemotherapy regimens can minimize severe adverse events and prolonged drug-free breaks. In addition, a more steady dosing schedule may actually kill more cancer cells by maintaining a more constant drug concentration in the body. This logic may explain why dose-dense regimens (chemotherapy regimens with an increased frequency of administration) have been shown to be more effective in the treatment of several kinds of cancer, including breast cancer, when compared to standard treatment. [5] We have also treated pancreatic cancer patients using a similar dosing strategy, which has yielded exciting results. [6,7]

The main mechanism of action of metronomic chemotherapy was initially thought to be its effects on endothelial cells resulting in antiangiogenic effects. There is a fair amount of literature that suggests that paclitaxel has antiangiogenic effects when administered in lower doses more frequently. [8] Likely due to their aggressive nature, TNBCs are known to have enhanced angiogenesis. [9] The proangiogenic tumor microenvironment creates an abnormal vascular network that can result in increased interstitial pressure and decrease drug penetration, ultimately decreasing the efficacy of systemic treatment. [10] By blocking angiogenesis and normalizing the tumor vasculature, more chemotherapy can reach the tumor, potentially improving the efficacy of treatment.

In addition to having direct cytotoxic and antiangiogenic effects, it has been discovered that metronomic chemotherapy can also have antistromal and immunostimulatory effects. [11–13] There are even some thoughts that the effects that metronomic chemotherapy has on the tumor microenvironment can decrease the rate of acquired chemotherapy resistance. [11,12] Targeting both cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment may play an important role in the future of cancer treatment.

3.2 Sequential chemotherapy regimens

The standard way to administer chemotherapy treatment is to continue a single chemotherapy regimen until noticeable disease progression. Patients with metastatic TNBC tend to relapse quickly on chemotherapy treatment, likely due to acquired disease resistance. [3] Drug resistance is seen as the primary cause of failure of chemotherapy treatment for cancer and continuing a chemotherapy regimen until disease progression will inevitably breed chemotherapy-resistant disease. Switching chemotherapy regimens before disease progression, as we did for this patient, may prevent the development of disease resistance, allowing for a continual decrease in the number of cancer cells, and perhaps a better chance of achieving long-term survival.

Tumors are known to have a large amount of genetic diversity, even within a single mass, and chemotherapy treatment can induce strong selective pressure for cells that have intrinsic or acquired mutations which can resist treatment. [14] Switching chemotherapy agents may eradicate cancer cells that developed resistance to the cytotoxic agents in the previous regimen, especially if the new chemotherapy agents have a different mechanism of action. There are even some suggestions that cancer cells can become dependent on certain therapies after long-term drug exposure, and switching the drugs used may increase treatment efficacy by inducing cell death of the cancer cells that have become “addicted” to the previous therapy. [12,13] The idea of switching chemotherapy treatments before the development of disease resistance has broad implications and could transform the idea of cancer being an acute disease to more of a chronic illness. In addition to potentially increasing treatment efficacy and preventing the development of disease resistance, switching treatment regimens can also help prevent the accumulation of chemotoxicity from a single chemotherapy regimen, which can improve the quality of life of patients receiving treatment.

This idea of sequential chemotherapy regimens has been successfully introduced in the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma. Patients who responded to first-line chemotherapy and pursued a switch maintenance therapy were found to have improved overall survival compared to placebo or observation, and switch maintenance therapy was also less toxic compared to continuous maintenance therapy. [15] A similar treatment strategy has also been applied and has found major success in the treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). A diagnosis of ALL was fatal for children in the 1950s. Currently, this disease has a cure rate of more than 80% in children. The current treatment for ALL involves several combination chemotherapy regimens that are given sequentially to eliminate any remaining disease. [16] Sequential chemotherapy regimens in ALL has been considered one of the greatest achievements in the field of oncology to date.

This patient received several different chemotherapy regimens sequentially ( Table 1 ). Her first regimen consisted of paclitaxel and carboplatin. Paclitaxel that is administered on a weekly basis has been shown to be superior to paclitaxel that is administered every 3 weeks in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, with increased response rates, time to progression, as well as survival. [17] Moreover, there is some evidence that platinum-based chemotherapy regimens improve the overall survival of patients with metastatic TNBC. [18] The addition of platinum agents to treatment regimens has likely been slow to catch on due to the significant toxicity of the standard doses of these agents. However, the carboplatin dose of AUC 2.25 and cisplatin dose of 15 to 20 mg/m 2 that was given on a weekly basis were tolerated relatively well by this patient.

After she received 14 doses of paclitaxel and carboplatin, she was switched to weekly doxorubicin liposome. Anthracyclines are known to be very effective in the treatment of breast cancer, but carry a risk of cardiotoxicity and significant myelosuppression. We prefer to use doxorubicin liposome instead of doxorubicin because doxorubicin liposome has a favorable toxicity profile, less hematological toxicity, and has been found to cause less cardiotoxicity compared to doxorubicin. [19] This is an important consideration to reduce potential comorbidities in the future, especially if patients have the potential to achieve long-term survival. The patient tolerated treatment with weekly doxorubicin liposome well aside from developing palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, but perhaps this treatment might be more tolerable if it was administered every 2 weeks due to doxorubicin liposome's relatively long half-life. This treatment might also be more effective if it was combined with weekly paclitaxel.

The patient's next regimen, gemcitabine, and cisplatin, has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with metastatic TNBC compared to patients without metastatic TNBC. [20] The patient also tolerated this regimen well aside from developing thrombocytopenia, but maybe this could be lessened by starting with a dose of gemcitabine 600 mg/m 2 and cisplatin 15 mg/m 2 instead of gemcitabine 750 mg/m 2 and cisplatin 20 mg/m 2 , which is what we have done subsequently with other patients. Her final regimen consisted of vinorelbine, which is another effective drug for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer patients who have been exposed to anthracyclines and taxanes in previous treatments. [21] Since the patient's diagnosis 15 years ago, there are several new treatments available that may be more effective than vinorelbine, such as eribulin or irinotecan.

By giving this series of effective treatments sequentially, we believe that this prevented disease resistance and allowed the patient to achieve complete remission after approximately 1 year of treatment. The combination of agents was chosen to avoid overly additive side effects, such as myelosuppression, so that the patient could receive continuous treatment without interruption and also maintain a relatively high overall dose intensity. In regards to the order of these regimens, it is unknown whether or not this is the most optimum sequence of regimens and this should be further investigated.

3.3 Immunotherapy

More evidence is accumulating suggesting that some subtypes of metastatic TNBC can be particularly responsive to immunotherapy, with some studies showing promising results. [22] However, cancers can escape an antitumor immune response in several ways such through the upregulation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines into the tumor microenvironment as well as through the expression of immunosuppressive proteins, such as programmed death-ligand 1, on the cell surface. [22–24] The situation is further exacerbated by the immunosuppressive effect of standard dose chemotherapy. [25] When the immunosuppressive activity of the tumor outweighs the body's antitumor immune response, this is thought to promote tumor progression.

Metronomic chemotherapy, in addition to having a lesser impact on blood counts, is thought to have immunomodulatory properties. In preclinical studies, low-dose paclitaxel and gemcitabine have been shown to decrease the number and viability of Tregs as well as myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which could potentially allow for a more potent antitumor immune response. [26] Moreover, the antiangiogenic effects of metronomic chemotherapy may be synergistic with its immunostimulatory properties. Normalizing the tumor vasculature could allow the immune system to better reach the tumor bed, just as it is thought to allow more chemotherapy treatment to reach the tumor. Interestingly, the patient also received zoledronic acid due to her bone metastases, which may also have immunomodulatory properties. This effect seems to be more prevalent in ER-positive breast cancer cells, but more research will need to be conducted to assess the immunomodulatory properties in ER-negative breast cancer. [27]

The patient also received several immunostimulatory agents which may have played a role in her long disease-free remission. While receiving chemotherapy treatment, the patient received GM-CSF to prevent or treat chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. We prefer the use of GM-CSF compared to other colony-stimulating factors because GM-CSF stimulates both the granulocyte as well as the monocyte/macrophage and dendritic cell (DC) lines, while other colony-stimulating factors only stimulate the granulocyte cell line. DCs are crucial for antigen presentation and activation of the adaptive immune system and macrophages can remove dead tumor cells via phagocytosis. Moreover, preclinical evidence suggests that low-dose paclitaxel can stimulate DC maturation and the anthracyclines can promote the phagocytosis of tumor cells by DCs, suggesting a synergistic role of GM-CSF in combination with 2 of the patient's chemotherapy regimens. [28]

The patient also applied imiquimod topically to small superficial lesions in her left axillary region that were likely secondary to recurrent disease. Imiquimod has known antitumor activity in superficial basal cell carcinoma and it is thought to work by stimulating the innate and adaptive immune system in the applied area via toll-like receptor 7. [29] The patient's left axillary lesions resolved after she applied imiquimod cream to the area, suggesting that imiquimod may be able to be used to treat superficial metastases from TNBC. One small study also had similar findings, and it would be interesting to investigate whether metastatic TNBC was more responsive to local immunotherapy than other breast cancer types. [30] Perhaps the success of imiquimod in this patient was due to the minimal tumor burden the patient had at the time, especially considering that a smaller tumor size in basal cell carcinoma is correlated with a more favorable prognosis after treatment with imiquimod.

4 Conclusion

The patient described in this case report is now 15 years out from her diagnosis of recurrent metastatic TNBC without evidence of persistent or recurrent metastatic disease. Her treatment, which included the use of sequential metronomic chemotherapy regimens as well as several immunotherapies, was tolerated relatively well and likely contributed to her remarkable survival. Although this is only 1 case, we have treated another patient with metastatic TNBC with a similar strategy who is now over 6 years out and free of disease as well as a few other patients who achieved longer than average survivals. We are planning to publish this data in a small case series in the future. We hope that this encouraging case can offer hope to those who are suffering from this debilitating disease and spark the formation of larger clinical trials to further evaluate this treatment strategy due to the potential significant medical, psychological, and economic implications. These ideas not only have the possibility to shift the paradigm of treating metastatic TNBC, but also potentially other metastatic cancers as well.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Max Tse and Jeffrey Wang for drafting earlier versions of this paper, and Emmanuel De Dios, without whom none of this work could have been done.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ben Man-Fai Chue, Bryce Douglas La Course.

Formal analysis: Ben Man-Fai Chue, Bryce Douglas La Course.

Writing – original draft: Ben Man-Fai Chue, Bryce Douglas La Course.

Writing – review and editing: Ben Man-Fai Chue, Bryce Douglas La Course.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

immunotherapy; long-term survival; metastatic triple-negative breast cancer; metronomic chemotherapy; sequential chemotherapy regimens

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Can we cure stage iv triple-negative breast carcinoma: another case report of....

CASE REPORT article

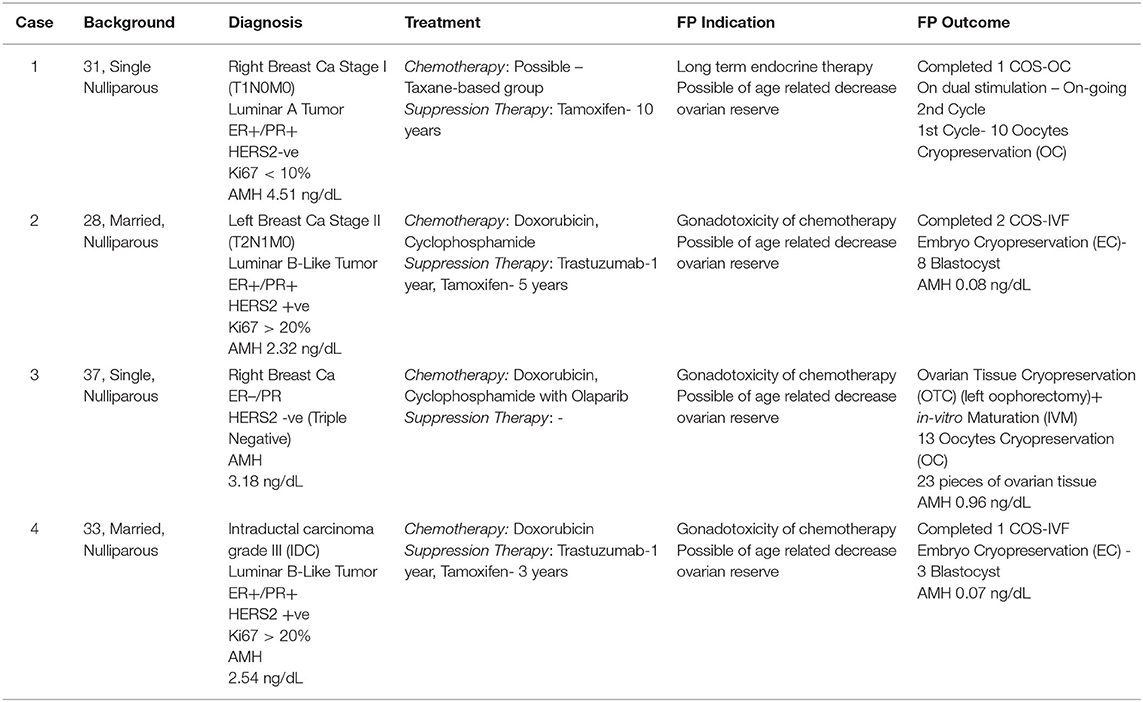

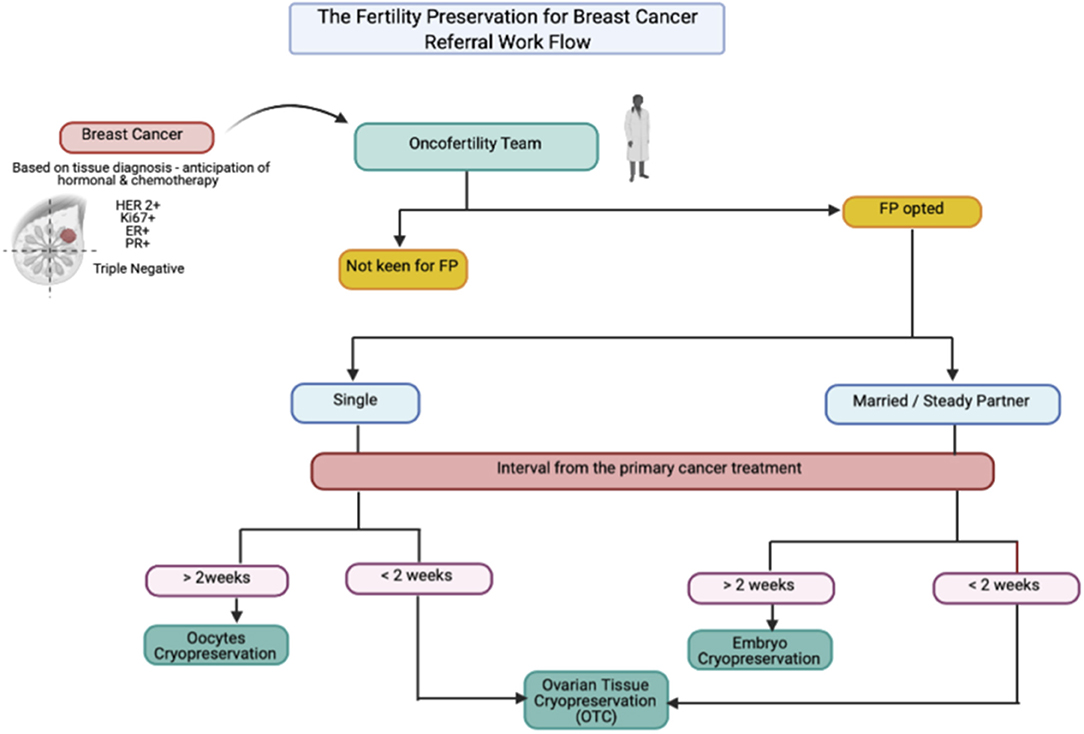

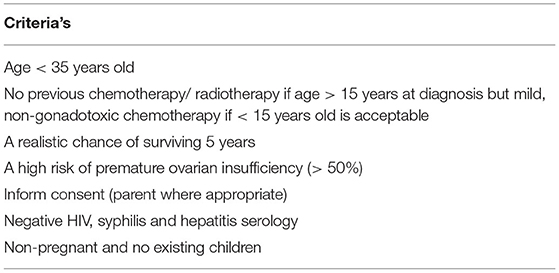

Case report: young adults with breast cancer: a case series of fertility preservation management and literature review.

- 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Japan

- 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 3 Laboratory of Cancer and Reproductive Science, Department of Frontier Medicine, St. Marianna University, School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Japan

- 4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Breast cancer comprised at least 21.8% of the overall cancer among young adult (YA) women and became the leading cancer in this group in Japan, with 50% adolescent and YAs being diagnosed and 15–44-year-old women showing excellent 5-year survival. Surgical-chemoradiation therapy often results in excellent survivorship with an increased incidence of treatment-induced subfertility. Therefore, adding fertility preservation (FP) to the primary cancer treatment is necessary. Herein, we reported a series of cases of YA women with breast cancer who opted for FP, where their option was tailored accordingly. To date, the selection of oocytes, embryos and ovarian tissue is widely available as an FP treatment. PGT could reduce the risk of BRCA mutation transmission amongst BRCA carriers before pregnancy planning. Otherwise, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog has no gonadoprotective effect and thus should not be considered as an FP option.

Introduction