Meta-analysis of the Factors Influencing the Employees’ Creative Performance

- Conference paper

- First Online: 29 June 2017

- Cite this conference paper

- Yang Xu 6 ,

- Ying Li 6 ,

- Hari Nugroho 7 ,

- John Thomas Delaney 8 &

- Ping Luo 6

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering ((LNMUINEN))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management

2667 Accesses

Innovation has become a popular topic in society. The creative performance fluctuates with the employees’ mood caused by the working environment. Many factors have been suggested to be affecting the employees’ creative performance. The paper answered the questions as “What are the factors that affect the employees’ creative performance through employee behavior? What is the proportion (weight) of each of these determinants?” Furthermore, this study resolves this problem via the meta-analysis, which refers to do systematic quantitative analysis by former studies to summarize the research results of creative performance over the last ten years, and to ascertain the factors influencing the creative performance as well as to determine the correlation between them. Suggestion having been proposed including the further investigation of the interaction between the factors impacting the employees’ creative performance as well as explore the corresponding effects. And it is necessary to note that changing one factor may eliminate the effect of several factors, which may cause negative change in the staff creative performance and there is joint efforts needed in terms of enhancing the employees’ creative performance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of employees’ creativity: modeling the mediating role of organizational motivation to innovate

Research on the cross-level influence mechanism of team emotional intelligence on employees’ creative self-efficacy and innovation performance: the moderating effect of team identification

Employee Performance, Working Time and Tiredness in Creative R&D Jobs: Employee Survey from Estonia

Chong E, Ma X (2010) The influence of individual factors, supervision and work environment on creative self-efficacy. Creativity Innov Manag 19(3):233–247

Article Google Scholar

Dong L, Zhang J, Li X (2012) Relationship between employee’s affect and creative performance under the moderation of autonomy orientation standard (in Chinese)

Google Scholar

Gong Z, Zhang J, Zheng X (2013) Study on feedback-seeking influence of creative performance and motive mechanism (in Chinese)

Huang L, Krasikova DV, Liu D (2016) I can do it, so can you: the role of leader creative self-efficacy in facilitating follower creativity. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 132:49–62

Song Y, He L et al (2015) Mediate mechanism between work passion and creative performance of employees. J Zhejiang Univ (Sci Ed) 42(6):652–659 (in Chinese)

Tang C, Liu Y, Wang T (2012) An empirical study of the relationship among charismatic leadership style, team identity and team creative performance in scientific teams. Sci Sci Manag S&T 33(10):155–162 (in Chinese)

Ulger K (2016) The creative training in the visual arts education. Thinking Skills Creativity 19(32):73–87

Zhang J (2003) Study on situational factors of employees creative performance and motive mechanism. Master’s thesis, Capital Normal University, Beijing (in Chinese)

Zhang J, Dong L, Tian Y (2010) Improve or hinderinfluence of affect on creativity at work. Adv Psychol Sci 6:955–962 (in Chinese)

Zhang J, Song Y et al (2013) Relationship between employees’ affect and creative performance the moderation role of general causality orientation. Forecasting 32(5):8–14 (in Chinese)

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Sichuan Social Science Planning Program Key Project (Grant No. SC16A006), System Science and Enterprise Development Research Center Project (Grant No. Xq16C12) and Sichuan University Central University Research Fund project (Grant No. skqy201653), Soft Science Project of Sichuan Science and Technology Department, (No. 2017ZR0033) and Sichuan Social Sciences Research 13th Five-Year annual planning project, (NO. SC16A006).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Business School, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610064, People’s Republic of China

Yang Xu, Ying Li & Ping Luo

Department of Sociology, Gedung F. Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia

Hari Nugroho

Kogod School of Business, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave, Washington, DC, 20016-8044, USA

John Thomas Delaney

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ying Li .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Business and Administration, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

Fuzzy Logic Systems Institute, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Baku, Azerbaijan

Asaf Hajiyev

Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

Fang Lee Cooke

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Xu, Y., Li, Y., Nugroho, H., Delaney, J.T., Luo, P. (2018). Meta-analysis of the Factors Influencing the Employees’ Creative Performance. In: Xu, J., Gen, M., Hajiyev, A., Cooke, F. (eds) Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management. ICMSEM 2017. Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59280-0_54

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59280-0_54

Published : 29 June 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-59279-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-59280-0

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Organizational climate and creative performance in the public sector

European Business Review

ISSN : 0955-534X

Article publication date: 6 May 2020

Issue publication date: 10 August 2020

The aim of this study is to examine the role of organizational climate in employees’ creative performance using the public sector as an empirical context. The employees’ creative performance is divided into two entities and studied as two separate effect variables: individual creativity and individual innovative behavior.

Design/methodology/approach

A conceptual model is developed and tested in a survey in which employees of a public sector organization participated.

The findings indicate that organizational climate has an important role in employees’ creative performance. The organizational climate showed a positive and significant link to the two creative performance variables included in this study. Moreover, the study revealed that individual creativity mediates the relationship between organizational climate and individual innovative behavior.

Research limitations/implications

This paper is limited to examining the role of organizational climate on two creative performance variables related to individual employees in the public sector. To trigger individual creativity and individual innovative behavior in the public sector, there is a need for managers to build, develop and maintain an organizational climate that supports both employees’ creativity and enthusiasm in implementing those novel and useful ideas.

Originality/value

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is among the first in the public sector to demonstrate the importance of organizational climate for employees’ individual creative performance. The findings of this study adds to our current knowledge and understanding of the value of organizational climate, and its influence on individual creative performance in the public sector.

Organizational climate

Individual creativity

Individual innovative behavior.

Mutonyi, B.R. , Slåtten, T. and Lien, G. (2020), "Organizational climate and creative performance in the public sector", European Business Review , Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 615-631. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-02-2019-0021

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Barbara Rebecca Mutonyi, Terje Slåtten and Gudbrand Lien.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Today, organizations face fast-paced changes that push them to face unpredictable challenges ( Anderson et al. , 2014 ). Accordingly, the need for creative performance, manifested as employees’ individual creativity (IC) and individual innovative behavior (IIB), is perceived as both a necessary and desired feature among a firm’s employees ( Imran et al. , 2010 ). This study defines IC as the individuals’ production of novel, useful ideas, that are appropriate to any given situation ( Amabile, 1988 ; Amabile et al. , 1996 ; Amabile et al. , 2005 ; Zhou and George, 2001 ). IIB is understood here as the set of activities and behaviors toward and during the process of innovation ( Janssen, 2005 ; West and Farr, 1989 ).

It is reasonable to assume that firms within the public and private sectors are concerned with the need for creative performance. Such factors as competitive advantage, survival and competitive power in a business environment can be characterized as turbulent and dynamic, both nationally and globally ( Miao et al. , 2018 ). Considering these environmental factors, Potočnik and Anderson (2012) argued for the importance of creative performance in the public sector because it is indispensable for organizational success and survival ( Choi and Chang, 2009 ; Imran et al. , 2010 ). In recent research, Miao et al. (2018) commented on the small amount of research examining the influence of creative performance in public sector organizations, especially when “innovation in public sector organizations has been linked to improved effectiveness, efficiency, and citizen involvement” (p. 71). Employees in the public sector are also heavily relied upon to bring innovation into their processes, operations and methods ( Imran et al. , 2010 ; Windrum and Koch, 2008 ). Aspects related to creative performance in the public sector have become a topic of great interest ( Bason, 2010 ; Borins, 2002 ; Cole and Parston, 2006 ) because of their core role in increasing “the responsiveness of services to local and individual needs, and to keep up with public needs and expectations” ( Mulgan and Albury, 2003 , p. 5).

Based on the discussion above, it is apparent that the organizational climate (OC) in the public sector plays an essential role in an employee’s creative performance. In this paper, OC is defined as individuals’ cognitive representations and psychological interpretations of their organizational setting ( Abbey and Dickson, 1983 ; Sarros et al. , 2008 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ).

Previous research has revealed that OC is “assumed by the employees through organization’s practices and procedures, which in turn formulate and shape their priorities” ( Imran et al. , 2010 , p. 3338). Most research on the role of OC for individual creative performance concentrates on private sectors ( Choi and Chang, 2009 ; De Jong and Den Hartog, 2007 ; Imran et al. , 2010 ; Slåtten and Mehmetoglu, 2015 ). In addition, “researchers […] have devoted increasing attention to organization and individual factors that potentially promote” IIB ( Shanker et al. , 2017 , p. 68). Moreover, Yuan and Woodman (2010) have pointed to how IIB can “assist organizations to gain competitive advantage and to enhance organizational performance” in the private sector ( Shanker et al. , 2017 , p. 68).

However, the relationship between OC and creative performance in the public sector is still largely unexplored ( Anderson et al. , 2014 ; Sarros et al. , 2008 ; Sexton and Barrett, 2005 ; Yuan and Woodman, 2010 ). Based on this seeming knowledge gap from previous research, this paper will examine how public sector organizations can manage to satisfy public expectations by acquiring and possibly increasing employees’ creative performance through OC.

It calls for more research on IIB in the public sector.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine employees’ perceptions about their OC and its role in individual creative performance, using the public sector as the empirical context.

It adds to the literature of public sector and public sector organizations, in the field of creative performance.

This article begins with a brief explanation of the suggested conceptual model for this study, followed by a literature review and hypotheses on the concept of OC, creative performance and the value of OC in creative performance. Next, the methodology is outlined, followed by a presentation of the analysis and the empirical findings. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications of the study, its limitations and suggestions for future research.

Conceptual model of the study

The aim of the study was to examine the role of OC for creative performance in the public sector. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of the study.

As can be seen in Figure 1 , the role of OC is suggested to be a cause variable in relation to the overall effect variable of creative performance. The creative performance variable is divided into two subcreative performance effect variables: each employee’s IC and IIB.

Four effects regarding the role of OC and IC are suggested in Figure 1 . First, OC has a direct effect on an employee’s IC. Second, OC has a direct effect on an employee’s IIB. Third, IC has a direct effect on IIB. Finally, the model suggests that IC mediates the relationship between OC and IIB. In the following section, the content of each construct in Figure 1 is discussed in more detail.

Literature review and hypotheses

Previous research has often highlighted OC as a crucial indicator necessary for observing an organization’s capacity to innovate ( Sarros et al. , 2008 ), while arguing that climate plays a crucial role on innovation in organizations, thus coming down to individual employees ( McLean, 2005 ; Schneider et al. , 2013 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ).

OC differs from organizational culture ( Amabile et al. , 1996 ), and while organizational culture has been extensively studied ( Anderson et al. , 2014 ), only a few studies concentrate on OC ( Imran et al. , 2010 ; Isaksen and Akkermans, 2011 ; Schneider et al. , 2013 ) . Isaksen and Akkermans (2011) and Schneider et al. (2013) emphasized that culture is a deep organizational structure rooted in values, meaning, beliefs and long-held assumptions, but climate is perceived as “the manifestation or practices and patterns of behavior rooted in the assumptions, meaning, and beliefs that make up a culture” ( McLean, 2005 , p. 229).

OC holds various definitions. Some scholars have suggested OC to channel and direct both attention and activities toward innovation within an organization ( Amabile et al. , 1996 ; Anderson and West, 1998 ; Anderson et al. , 2014 ). Others have defined OC as consisting of “individual cognitive representations of the organizational setting” ( Scott and Bruce, 1994 , p. 581), which reflect the psychological interpretations of any given situation ( Abbey and Dickson, 1983 ; Sarros et al. , 2008 ). Zhou and Shalley (2003) have argued that climate refers to an individual’s visible experiences and perceptions.

In this paper, OC is defined as individuals’ cognitive representations and psychological interpretations of their organizational setting ( Abbey and Dickson, 1983 ; Sarros et al. , 2008 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ).

It is reasonable to assume that several aspects are related to an employee’s experiences and perception of OC. Consequently, several potential factors could serve as input for the OC construct chosen for this study. Scott and Bruce (1994) identified three core categories of factors associated with any OC, namely, leadership, co-workers and individual attributes, and these are used in the present study with minor modifications. The reason for this choice is twofold. First, the three categories are linked to different levels of factors affecting employees’ perceptions of OC. Second, previous research has linked the three categories of OC to different aspects related to innovation within organizations ( Amabile et al. , 1996 ; Janssen, 2005 ; Sanders et al. , 2010 ; Shalley and Gilson, 2004 ; Yuan and Woodman, 2010 ).

Though the three factors suggested by Scott and Bruce (1994) capture the concept of OC, it is difficult to identify these factors. To illustrate, leadership can represent several leadership styles, such as transformational leadership or transactional leadership. The same is true with the other two categories, co-workers and individual attributes. As a result, this study focused on the role of OC in relation to creative performance. The OC factors were chosen based on three criteria: it had been related to aspects of creative performance; it had a logical connection with creative performance; and it remained within the set definition of OC selected for this study, that is, OC is defined as individuals’ cognitive representations and psychological interpretations of their organizational setting ( Abbey and Dickson, 1983 ; Sarros et al. , 2008 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ). Based on the three criteria mentioned above, the three attributes were slightly modified: leadership became empowering leadership; individual attributes became individual learning orientation; and co-workers was replaced by work group cohesiveness. These changes will reflect the OC in a clear and precise manner.

It is important to note that the chosen variables serve as one way to study the value of OC in employees’ creative performance. Moreover, this study focuses on employees’ overall perceptions – the cognitive and psychological interpretation of their organizational setting. Therefore, the focus is on how OC is collectively perceived within an organization, in line with previous research that often referred to climate as a person’s perception of the entire organization ( Zhou and Shalley, 2007 ).

Organizational climate and creative performance

Recently, Tan et al. (2019) found that creativity-related activities, such as IC and IIB, improved overall self-rated creativity, which in turn improved the organizations’ performance. Previous research has highlighted the benefits of creative performance as a positive influence on overall organizational performance ( Tierney and Farmer, 2011 ), but there is a paucity of research that has examined the influence of employees’ OC on creative performance. While Shalley et al. (2009) investigated the influence of creative performance on individuals who worked for pay for at least 30 h per week, the present study narrowed the focus down to the creative performance of employees in the public sector. In addition, the recent study by Martinaityte et al. (2019) called for further research on creative performance in organizations; this study answers that call by focusing on the public sector. In Figure 1 , OC is directly linked to the employee’s creative performance. Here, the employee’s creative performance is an umbrella concept that consists of the two core factors, IIB and IC. The proposed relationships in Figure 1 will be elaborated in more detail below.

IIB has long been recognized as a crucial factor in facilitating innovation within an organization ( Isaksen and Akkermans, 2011 ; Slåtten, 2011 ; Yuan and Woodman, 2010 ; Zhou and Shalley, 2003 ). Previous research has defined IIB in several ways. For example, IIB has been described as how an individual recognizes a problem, generates ideas or solutions and sets a course in implementing the perceived solution ( King, 1992 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ). Other scholars have defined IIB as a multistage process, containing various activities that enable different individual behaviors at each stage ( Scott and Bruce, 1994 ; Xerri and Brunetto, 2013 ). According to this latter definition, it is believed that IIB is first enabled when the production of new ideas occurs, and second, when the environment is suitable to implement creative ideas ( Scott and Bruce, 1994 ; Yuan and Woodman, 2010 ).

This study defines IIB, in line with Janssen (2005) and West and Farr (1989) , as the set of activities and behaviors toward and during the process of innovation (i.e. an individual’s search for new technology or processes and suggestions for new ways of achieving goals). The goal is to benefit work-role performance, the work unit or the organization ( Janssen, 2003 ; Janssen, 2005 ). Consequently, the nucleus of IIB is that an individual is able to adopt, implement or make use of a creative idea ( Yuan and Woodman, 2010 ).

IIB related to cognition or a person’s creative thoughts; and

IIB related to a person’s actual act or behavior, adoption or implementation of new and useful ideas.

In this study, the latter is considered when defining IIB, and the study focuses on the action or the behavioral aspect of innovation.

OC is positively related to IIB.

For organizations to benefit fully from their employees’ creative potential, it is essential to understand the drivers of employees’ IC. Rego et al. (2012) note that IC “is a function of individual and social/contextual factors” (p. 429), and the most relevant contextual factor of IC is OC. OC refers to “behaviors, attitudes and feelings” that an individual employee finds at their workplace ( Ekvall and Ryhammar, 1999 , p. 303). Previous studies have focused on identifying how OC influences specific areas of creativity ( Büschgens et al. , 2013 ; Li et al. , 2018 ; McLean, 2005 ). The characteristics and definition of IC follow in the next section.

Amabile et al. (1996) studied the role of work environment in creativity and argued that “social environment can influence both the level and the frequency of creative behavior” (p. 1155). Schneider et al. (2013) recently noted that OC should entail shared perceptions behind all that affects employees at work. In other words, Schneider et al. (2013) suggested that climate is behaviorally oriented. Patterson et al. (2005) supported this notion by arguing that OC “is more behaviorally oriented in…” (p. 381) creative climates. The review study performed by Hunter et al. (2007) revealed that OC had a positive influence on individual employees’ creativity. Hunter et al. (2007) also termed OC as “localized phenomena.”

OC is positively related to IC.

Mediating role of individual creativity

Creativity is a field that has been highly studied because of its increasing importance in the workplace ( Amabile et al. , 1996 ; Amabile et al. , 2005 ; Anderson et al. , 2014 ; Ekvall and Ryhammar, 1999 ; Zhou and Shalley, 2003 ). According to Figure 1 , the relationship between OC and IIB can be influenced by other factors. Therefore, the study proposes that IC partially explains the effects of OC on IIB ( Sarros et al. , 2008 ). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine the mediating role of IC on IIB.

Creativity has been understood as the production of new and valuable ideas ( Amabile, 1988 ). Drawing on Amabile et al. (1996) and Zhou and George (2001) , this study defines IC as the individual’s production of novel ideas that are useful and appropriate to any given situation. In other words, IC is the tendency to generate or recognize ideas, alternatives or possibilities that may be useful in solving problems.

Amabile et al. (2005) differentiated creativity from innovation, arguing that the production of new and valuable ideas is creativity and that the successful implementation of the creative ideas within an organization is innovation ( Isaksen and Akkermans, 2011 ; Isaksen and Treffinger, 2004 ; Shalley and Gilson, 2004 ). Moreover, Yuan and Woodman (2010) argued that the generation of creative ideas is only a component of IIB; accordingly, it is assumed that only with the implementation of new ideas can one achieve a successful innovation ( Isaksen and Tidd, 2007 ). For this reason, creativity would have to precede innovation ( Isaksen and Akkermans, 2011 ; Mathisen and Einarsen, 2004 ). Amabile et al. (1996) believe that “all innovation begins with creative ideas” (p. 1154), and it is considered that while creativity can proceed without innovation, successful innovation is more likely when it begins with creativity ( Isaksen and Tidd, 2007 ). It is complex to proceed with innovation without creativity ( Mathisen and Einarsen, 2004 ). Yuan and Woodman (2010 , p. 324) argued that “creative behavior concerns new idea generation, whereas innovative behavior includes both the generation and implementation of new ideas,” although both of them are necessary to achieve positive IIB at work ( Hunter et al. , 2007 ).

IC is positively related to IIB.

IC mediates the relationship between OC and IIB.

Methodology

In their recent review, De Vries et al. (2016) called for more survey methods in the research area of innovation in the public sector. As an answer to that call, this paper empirically and quantitatively examines the role of OC in employees’ creative performance in the public sector through survey data.

Participants and procedure

Data for this study were collected from one of the largest government-owned transportation organizations in Norway, where innovation and innovative work are centered. The organization offers transportation services to the public and has a geographical coverage throughout Norway. The organization primarily deals with transporting passengers and goods, and is today one of the largest ground transportation companies in Norway. The employees consist of a mix of individuals who often have work tasks that are monotonous, semi-autonomous and self-directed. The participants were from diverse functional backgrounds, including customer services, operations, marketing, human resources and finance, with offices and branches across Norway. Consequently, the employees in the public sector organization chosen for this study provided a suitable context for examining the role of OC in employees’ creative performance. OC was defined as an individual’s cognitive representation of an employee’s organizational setting ( Scott and Bruce, 1994 ). All of the organizational members at the public transportation company were, therefore, able to interpret their organizational setting.

The collection of data was accomplished through an online questionnaire distributed by official e-mails to 256 employees in the spring of 2016. Because the study mainly focused on the public sector, the population size was restricted to one public organization through convenience sampling. Employees with management or leadership positions were excluded because the study focused on those employees with no managerial positions. Prior to participation, the study was reported to the NSD[ 1 ] because voluntary participation was guaranteed and anonymity was assured.

In total, responses from 96 employees in five different departments were obtained, representing an overall response rate of 37.5%. Previous research on fostering IIB by Xerri and Brunetto (2013) gathered data from participants in both the public and private sectors, and had a response rate of 21%. As such, the 37.5% response rate in this study is considered adequate in this current cross-sectional study. Of the 96 employees, 56.3% were female, the average age was 41–50 years and 79% worked full-time. Further participant profile details are provided in Table 1 .

In assessing the role of OC in employees’ creative performance, the study relied on employees’ cognitive representations and psychological interpretations of their organizational setting ( Abbey and Dickson, 1983 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ). The questionnaire consisted of three main sections that enveloped the three constructs in the conceptual model in Figure 1 . The questionnaire was structured, using statements that the participants rated using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”.

OC was measured by three subcategories adopted from Scott and Bruce (1994) : empowering leadership, work group cohesiveness and individual learning orientation. Items for OC were adopted from Amabile et al. (1996), Amundsen and Martinsen (2014) , Scott and Bruce (1994) and Sujan et al. (1994) . An example item is “Around here, it is allowed for employees to try and solve the same problem in different ways.” The eight items used to measure OC were found to be consistent, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.86.

In this study, creative performance was viewed as an umbrella concept, consisting of two core factors, IC and IIB. The four items used to measure IC were inspired by and modified from Zhou and George (2001) . An example item is, “I often have new ideas to accomplish my work tasks.” The scale was found to be reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.84. IIB was measured using five items inspired by Scott and Bruce (1994) (e.g. “I promote my ideas so that others can use them in their work tasks”). The Cronbach’s alpha for the five items used for IIB was 0.85, demonstrating a reliable scale.

Control variables

According to Bos-Nehles and Veenendaal (2017) , control variables such as age, tenure and education can potentially influence IIB because “these characteristics may be reflected in different characteristics of organizations” (p. 11). Consequently, the study controlled for several semi-demographic characteristics: age, gender, education level, tenure, job classification and the type of employment (part-time or full-time). No significant differences were found for the semi-demographic variables, so the control variables were excluded from further analysis.

Data analysis and results

Partial least-square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), with Stata version 15.1 is an appropriate tool for small sample data and was applied to analyze the reliability and validity of the reflective measurement model and to assess the structural model ( Hair et al. , 2016 ).

As a first step, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the reflective measurement model of the study was performed ( Mehmetoglu and Jakobsen, 2017 ). As seen in Table 2 , the results of the CFA demonstrated satisfactory properties for all variables. The composite reliability for all factors was above the suggested value of 0.6 ( Bagozzi and Yi, 2012 ), thereby indicating good internal consistency in the constructs of this study (OC, IC and IIB). According to Hair et al. (2011) , the average variance extracted (AVE) value should not show values that are lower than 0.5. All the variables in this study showed an AVE value higher than 0.5, indicating a satisfactory degree of convergent validity. In addition, the AVE for each latent variable showed higher values than the squared interfactor correlation between OC, IC and IIB (see Table 3 ), indicating discriminant validity.

As a second step, several tests were completed, as suggested by Hair et al. (2019) , to help evaluate the structural model of the study. The results from the variance inflation factor test showed that all the variables in this study were found to be below the suggested level of 3.0, indicating no problems with multicollinearity. Because the conceptual model of the study consisted of reflective latent indicators, the extent to which each construct was “empirically distinct from” other constructs was also tested ( Hair et al. , 2016 , p. 112). Consequently, based on the bootstrap method, discriminant validity was verified. All of the indicators’ loadings on their associated constructs (OC, IC and IIB) were higher than the cross-loadings on other constructs. For example, assessment of the internal consistency of the conceptual model, in accordance with the guidelines of Hair et al. (2019) , showed that all of the indicator loadings were within the accepted range of 0.70–0.90, while the cross-loadings were found outside of the range. To evaluate the quality of the study’s hypothesized model further ( Figure 2 ), the bootstrapping method was used to obtain path coefficient (standardized) and coefficient of determination ( R 2 ) ( Hair et al. , 2019 ; Venturini and Mehmetoglu, 2017 ).

The results from the PLS-SEM analysis are presented in Figure 2 . OC was found to have a positive and significant relationship with the two creative performance variables. As hypothesized, OC was found to be positively related to IIB ( β = 0.442). Figure 2 also shows that the relationship between OC and IC was positive and significant ( β = 0.548), supporting H2 . H3 was also supported because the relationship between IC and IIB was positive and significant ( β = 0.385, p < 0.001). OC and IC together explained 52% ( R 2 ) of the variance of IIB, showing a substantial result. Moreover, OC explained 29% ( R 2 ) of the variance of IC.

To test the mediating effect of IC ( H4 ), the study applied the bootstrap method suggested by Venturini and Mehmetoglu (2017) , by first estimating the indirect effects and then testing the statistical significance ( Hair et al. , 2016 ). The results showed that the mediating effect of IC on the relationship between OC and IIB was significant ( β = 0.211), supporting the H4 .

Theoretical implications

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of OC in employees’ creative performance in a public sector organization. More precisely, this study explored the effects of OC on IC and IIB, the effect of IC on IIB and examined the mediating role of IC. This study helps address the knowledge gap mentioned by Anderson et al. (2014) , Bos-Nehles and Veenendaal (2017) and Shanker et al. (2017) , who all noted a lack of research on the role of OC in employees’ creative performance in the public sector. Furthermore, this paper contributes to the literature that emphasizes public sector organizations ( Miao et al. , 2018 ) in the field of employee creative performance. In addition, the study answers the call for a more quantitative approach in the public sector ( De Vries et al. , 2016 ), and for furthering the current understanding of the innovative behaviors of employees employed in the public sector ( Orcutt and AlKadri, 2009 ).

The results show that OC has a significant and positive relationship with employees’ creative performance. This study supports earlier research, which suggests that to sustain or increase an employee’s creative performance, one needs an OC conducive to innovation ( Bos-Nehles and Veenendaal, 2017 ; Sarros et al. , 2008 ). Most of the studies that have examined the relationship between OC and creative performance have focused on employees in the private sector ( Imran et al. , 2010 ). Although the findings of this study do not contradict previous findings, they highlight OC as an important variable for observing the influence public organizations have on employees’ creative performance ( Sarros et al. , 2008 ).

As previously mentioned, this study divided the creative performance variable into two entities, IIB and IC. This enabled further exploration of the role of OC on IIB and IC. The results showed that the employees’ representation of their organizational setting had a positive influence on IIB in the public sector. Thus, in line with Yuan and Woodman (2010) , when an environment is suitable for innovation, it is easier to sustain and engage a positive IIB among employees, making it possible for employees to adopt and implement ideas in their work in the public sector. The results of the study further showed that whether OC is found in the private or public sector, it influences how an employee in a given organization can channel and direct both their attention and activities toward innovation ( Amabile et al. , 1996 ; Anderson et al. , 2014 ; Bos-Nehles and Veenendaal, 2017 ).

H2 suggested that the perceived OC of an employee would have a positive impact on IC. The study is unique in revealing the relationship between OC and IC from the perspective of employees in the public sector, and arguing that one can nurture individual creativity through OC.

The study also hypothesized and established that employees who perceived their level of creativity to be good or above average were more likely to attain positive IIB in the public sector. In the footsteps of Amabile (1988) , this study differentiated IC from IIB. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that has studied the influence of IC on IIB in the public sector. Although previous studies have had a tendency to define IC and IIB interchangeably ( Scott and Bruce, 1994 ), IC is a component of innovation ( Yuan and Woodman, 2010 ). Therefore, successful innovation will only occur once new ideas are implemented ( Isaksen and Tidd, 2007 ). Isaksen and Akkermans (2011) considered that while organizational performance hinges on various pillars, IC is the most prominent. Here, we contribute to the knowledge by empirically studying IC and IIB as two separate constructs. For this reason, the direct effect of IC on IIB, as well as the mediating role of IC on OC and IIB, is a significant contribution.

Practical implications

Prior to increasing employees’ creative performance, organizations need to acquire and sustain a climate conducive to innovation. Previous research shows that the level of an employee’s creative performance often depends on the organization’s climate. The present study focused on uncovering the role of OC on an employee’s creative performance. Thus, this study contributes to organizations within the public sector. In particular, leaders and managers who wish to encourage, motivate and invest in their employees’ creative performance should pay more attention to their organization’s climate ( Imran et al. , 2010 ).

OC is composed of three underlying constructs: empowering leadership, work group cohesiveness and individual learning orientation. This study shows that there is a positive relationship between OC and IIB in the public sector. Previous research has observed OC to be crucial to an individual’s capacity to innovate in the private sector ( Sarros et al. , 2008 ). Managers in the public sector are encouraged to seek improvements, as well as creating or sustaining a climate supportive of innovation ( Orcutt and AlKadri, 2009 ). OC also represents an individual’s cognitive and psychological interpretations of their organizational setting ( Sarros et al. , 2008 ; Scott and Bruce, 1994 ), and is a central factor in how an individual chooses to approach innovation at work. Therefore, it is crucial that managers in the public sector recognize that the climate, in general, differs greatly from one employee to another. For instance, in a study by Orcutt and AlKadri (2009) on barriers to and enablers of innovation, they found that 63% of the respondents considered themselves champions of innovation. As such, what is valuable to one individual might not be the same for another. Leaders in the public sector should be eager to create a climate conducive to innovation, to influence or change employees’ cognitive representations and psychological interpretations of their organizational setting because it results in an increase in employees’ creative performance.

The results also demonstrate that a desirable OC has an effect on an employee’s IC. The implications of the relationship between OC and IC are that managers need to provide a learning arena so that teams can function well together, and encourage employees themselves to lead. This would motivate IC and sustain positive creative behavior among their employees. In their review of climate and creativity, Hunter et al. (2007) suggested that some predictors that are effective for creative performance are found in the OC. In addition, the recent study by Martinaityte et al. (2019) emphasizes the importance of fostering employees’ creative performance. For instance, it not only affects high-performance work systems but can also positively influence customer satisfaction. While Martinaityte et al. (2019) focused on retail banks and cosmetics in the private sector, this study has focused on the public sector. It is evident that the way an organization’s climate is constructed contributes a great deal to IC in the public sector.

This study has viewed IC as the individual’s production of novel and useful ideas ( Amabile et al. , 1996 ; Zhou and George, 2001 ). The direct effect of IC on IIB and the mediating role of IC on OC and IIB were examined. The results suggest that successful innovation in the public sector will most promptly occur when new and useful ideas are implemented ( Isaksen and Tidd, 2007 ). However, a study by Malik et al. (2015) argued for the importance of differentiating between employees at work when it came to their level of creativity because their motivation to introduce and implement new ideas at work was dependent on individual differences. While the study by Malik et al. (2015) focused on private universities, this study offers fresh insights on creative performance in the public sector. It is therefore important that organizations in this sector work hard to create and sustain a climate that welcomes IC, and where individuals are free to use their creative skills in solving a task. Ultimately, this will contribute positively to increase IIB ( Shalley and Gilson, 2004 ). Leaders in public sector organizations are encouraged to search for and retain creative individuals while also helping to create and sustain a climate favorable to innovation. Fernandez and Moldogaziev (2012) examined the role of employee empowerment on innovative behavior in the public sector and found that empowerment positively increases the encouragement to innovate. Although their study focused on US federal government employees, the current study offers new insights on employees in the public sector; managers in the public sector can motivate, support and encourage new ideas, better ways or new ways of solving problems at work.

Limitations and future research

This study contributed by exploring public sector employees’ perceptions of their OC. The study looked at one public sector organization at one given time, so the insights provided may offer limited generalizability to other public sector organizations. Although the study answered the call for more cross-sectoral studies in public sector innovation ( De Vries et al. , 2016 ), a limitation is its relatively small sample size, and as such, the results should be interpreted with caution. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies should broaden the present findings, and explore whether the same is true in other public organizations.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first empirical study to examine individuals’ perceptions about their OC in a public sector. It is notable that in this study, OC was significant to employees’ creative performance. Future studies should include other variables for studying IIB, such as the consequences of IIB on an employee’s commitment to the organization, or look into other dimensions, such as organizational culture.

In this study, it was assumed that OC comprised three underlying constructs: empowering leadership, work group cohesiveness and individual learning orientation. Although the current study found OC to be a positive influence on employees’ creative performance, future research should exploit other factors that can alter employees’ IC and IIB, such as the value of IIB in employer attractiveness, or the relationship between psychological capital and IIB.

To conclude, the aim of this study was to examine the role of OC for employees’ creative performance using the public sector as an empirical context. The study therefore proposed and tested the direct and indirect effects of OC and IC on IIB. The findings revealed that an OC conducive to innovation provides nutriments to motivate employees’ IC, which in turn influences the employees’ level of IIB. IC also has a positive influence on IIB. This study, therefore, contributes to the literature by addressing the knowledge gap on employees’ creative performance in three ways: calling for more research on IIB in the public sector; empirically examining employees’ perceptions about their OC and the role of individual creative performance; and adding to the public sector literature in the field of creative performance. We hope that the findings in this study, as well as the abovementioned directions for future research, will inspire further investments in research efforts in the role of IIB in public sector organizations. Consequently, it might extend the existing knowledge and understanding of how IIB can be fostered to increase an organization’s competitive advantage or capability in other areas within the public sector. This study highlights that although there is growing literature on OC and IIB in the public sector, much remains to be studied.

Structural model results

Respondents’ sample characteristics ( n = 96)

| Section | Frequency | (%) |

| | | |

| Male | 54 | 56.25 |

| Female | 42 | 43.75 |

| | | |

| 21–30 | 23 | 23.96 |

| 31–40 | 19 | 19.79 |

| 41–50 | 31 | 32.29 |

| 51–60 | 21 | 21.88 |

| 61+ | 2 | 2.08 |

| | | |

| Sales | 65 | 67.71 |

| IT | 12 | 12.50 |

| Market | 9 | 9.38 |

| HR | 3 | 3.13 |

| Finance | 7 | 7.29 |

| | | |

| Primary school | 1 | 1.04 |

| High school | 27 | 28.13 |

| Certificate of apprenticeship | 10 | 10.42 |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s | 58 | 60.42 |

| | | |

| Full-time | 77 | 80.21 |

| Part-time | 19 | 19.79 |

| | | |

| Under a year | 10 | 10.42 |

| 1–5 year(s) | 29 | 30.21 |

| 6–10 years | 15 | 15.63 |

| 11–15 years | 14 | 14.58 |

| 16–20 years | 11 | 11.46 |

| 20+ | 17 | 17.71 |

Measurement model results, CFA

| Constructs | Indicators | Loadings | CR(DG) | AVE | |

| Individual innovative behavior (IIB) | | 0.896 | 0.634 | 0.85 |

| | I try out new technology, processes and techniques to complete my work | 0.739 | | | |

| | I promote my ideas so that others might use them in their work | 0.800 | | | |

| | I investigate and find ways to implement new ideas | 0.885 | | | |

| | I develop plans and schedules to realize my ideas | 0.699 | | | |

| | I try out new ideas in my work | 0.842 | | | |

| Individual creativity (IC) | | 0.891 | 0.667 | 0.84 |

| | I exhibit creativity at work when given the opportunity to | 0.750 | | | |

| | I often have new ideas to accomplish my work task | 0.867 | | | |

| | I often come up with creative solutions to problems | 0.828 | | | |

| | I generally have many creative ideas | 0.816 | | | |

| Organizational climate (OC) | | 0.892 | 0.509 | 0.86 |

| | My leader assigns responsibility | 0.720 | | | |

| | My leader encourages me to take initiative | 0.792 | | | |

| | My leader listens to me | 0.794 | | | |

| | It is permitted for employees to solve the same problem in different ways | 0.594 | | | |

| | There is a high “ceiling” for making mistakes among colleagues | 0.708 | | | |

| | I learn new things in my work | 0.685 | | | |

| | It is worth spending a great deal of time learning new ways to accomplish my work | 0.702 | | | |

| | I acquire new knowledge when it is necessary | 0.694 | | | |

Notes: : Cronbach’s alpha; CFA: confirmatory factor analysis. All of the loadings are statistically significant | | IIB | IC | OC |

| IIB | 1.000 | 0.393 | 0.426 |

| IC | 0.393 | 1.000 | 0.300 |

| OC | 0.426 | 0.300 | 1.000 |

| AVE | 0.634 | 0.667 | 0.509 |

AVE: average variance extracted; IIB: individual innovative behavior; IC: individual creativity; OC: organizational climate

Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD).

Abbey , A. and Dickson , J.W. ( 1983 ), “ R&D work climate and innovation in semiconductors ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 362 - 368 .

Amabile , T.M. ( 1988 ), “ A model of creativity and innovation in organizations ”, Research in Organizational Behavior , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 123 - 167 .

Amabile , T.M. , Barsade , S.G. , Mueller , J.S. and Staw , B.M. ( 2005 ), “ Affect and creativity at work ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 50 No. 3 , pp. 367 - 403 .

Amabile , T.M. , Conti , R. , Coon , H. , Lazenby , J. and Herron , M. ( 1996 ), “ Assessing the work environment for creativity ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 39 No. 5 , pp. 1154 - 1184 .

Amundsen , S. and Martinsen , Ø.L. ( 2014 ), “ Empowering leadership: construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale ”, The Leadership Quarterly , Vol. 25 No. 3 , pp. 487 - 511 .

Anderson , N. and West , M. ( 1998 ), “ Measuring climate for work group innovation: development and validation of the team climate inventory ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 235 - 258 .

Anderson , N. , Potočnik , K. and Zhou , J. ( 2014 ), “ Innovation and creativity in organizations: a state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 40 No. 5 , pp. 1297 - 1333 .

Bagozzi , R.P. and Yi , Y. ( 2012 ), “ Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 40 No. 1 , pp. 8 - 34 .

Bason , C. ( 2010 ), Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-Creating for a Better Society , Policy Press , Bristol .

Borins , S. ( 2002 ), “ Leadership and innovation in the public sector ”, Leadership and Organization Development Journal , Vol. 23 No. 8 , pp. 467 - 476 .

Bos-Nehles , A.C. and Veenendaal , A.A. ( 2017 ), “ Perceptions of HR practices and innovative work behavior: the moderating effect of an innovative climate ”, International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 30 No. 18 , pp. 1 - 23 .

Bos-Nehles , A. , Renkema , M. and Janssen , M. ( 2017 ), “ HRM and innovative work behaviour: a systematic literature review ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 46 No. 7 , pp. 1228 - 1253 .

Büschgens , T. , Bausch , A. and Balkin , D.B. ( 2013 ), “ Organizational culture and innovation: a meta-analytic review ”, Journal of Product Innovation Management , Vol. 30 No. 4 , pp. 763 - 781 .

Choi , J.N. and Chang , J.Y. ( 2009 ), “ Innovation implementation in the public sector: an integration of institutional and collective dynamics ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 94 No. 1 , pp. 245 - 253 .

Cole , M. and Parston , G. ( 2006 ), Unlocking Public Value: A New Model for Achieving High Performance in Public Service Organizations , John Wiley and Sons , NJ, New York, NY .

De Jong , J.P. and Den Hartog , D.N. ( 2007 ), “ How leaders influence employees’ innovative behaviour ”, European Journal of Innovation Management , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 41 - 64 .

De Vries , H. , Bekkers , V. and Tummers , L. ( 2016 ), “ Innovation in the public sector: a systematic review and future research agenda ”, Public Administration , Vol. 94 No. 1 , pp. 146 - 166 .

Ekvall , G. and Ryhammar , L. ( 1999 ), “ The creative climate: its determinants and effects at a Swedish university ”, Creativity Research Journal , Vol. 12 No. 4 , pp. 303 - 310 .

Fernandez , S. and Moldogaziev , T. ( 2012 ), “ Using employee empowerment to encourage innovative behavior in the public sector ”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 155 - 187 .

Hair , J.F. , Hult , G.T.M. , Ringle , C. and Sarstedt , M. ( 2016 ), A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) , 2nd ed. , Sage Publications , Thousand Oaks, CA .

Hair , J.F. , Ringle , C.M. and Sarstedt , M. ( 2011 ), “ PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet ”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice , Vol. 19 No. 2 , pp. 139 - 152 .

Hair , J.F. , Risher , J.J. , Sarstedt , M. and Ringle , C.M. ( 2019 ), “ When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM ”, European Business Review , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 2 - 24 .

Hunter , S.T. , Bedell , K.E. and Mumford , M.D. ( 2007 ), “ Climate for creativity: a quantitative review ”, Creativity Research Journal , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 69 - 90 .

Hurley , R.F. and Hult , G.T.M. ( 1998 ), “ Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: an integration and empirical examination ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 62 No. 3 , pp. 42 - 54 .

Imran , R. , Saeed , T. , Anis-Ul-Haq , M. and Fatima , A. ( 2010 ), “ Organizational climate as a predictor of innovative work behavior ”, African Journal of Business Management , Vol. 4 No. 15 , p. 3337 .

Isaksen , S.G. and Akkermans , H.J. ( 2011 ), “ Creative climate: a leadership lever for innovation ”, The Journal of Creative Behavior , Vol. 45 No. 3 , pp. 161 - 187 .

Isaksen , S.G. and Tidd , J. ( 2007 ), Meeting the Innovation Challenge: Leadership for Transformation and Growth , Wiley , West Sussex .

Isaksen , S.G. and Treffinger , D.J. ( 2004 ), “ Celebrating 50 years of reflective practice: versions of creative problem solving ”, The Journal of Creative Behavior , Vol. 38 No. 2 , pp. 75 - 101 .

Janssen , O. ( 2003 ), “ Innovative behaviour and job involvement at the price of conflict and less satisfactory relations with co-workers ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 76 No. 3 , pp. 347 - 364 .

Janssen , O. ( 2005 ), “ The joint impact of perceived influence and supervisor supportiveness on employee innovative behaviour ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 78 No. 4 , pp. 573 - 579 .

King , N. ( 1992 ), “ Modelling the innovation process: an empirical comparison of approaches ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 65 No. 2 , pp. 89 - 100 .

Lee , H. and Choi , B. ( 2003 ), “ Knowledge management enablers, processes, and organizational performance: an integrative view and empirical examination ”, Journal of Management Information Systems , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 179 - 228 .

Li , W. , Bhutto , T.A. , Nasiri , A.R. , Shaikh , H.A. and Samo , F.A. ( 2018 ), “ Organizational innovation: the role of leadership and organizational culture ”, International Journal of Public Leadership , Vol. 14 No. 1 , pp. 33 - 47 .

McLean , L.D. ( 2005 ), “ Organizational culture’s influence on creativity and innovation: a review of the literature and implications for human resource development ”, Advances in Developing Human Resources , Vol. 7 No. 2 , pp. 226 - 246 .

Malik , M.A.R. , Butt , A.N. and Choi , J.N. ( 2015 ), “ Rewards and employee creative performance: moderating effects of creative self-efficacy, reward importance, and locus of control ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 59 - 74 .

Martinaityte , I. , Sacramento , C. and Aryee , S. ( 2019 ), “ Delighting the customer: creativity-oriented high-performance work systems, frontline employee creative performance, and customer satisfaction ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 45 No. 2 , pp. 728 - 751 .

Mathisen , G.E. and Einarsen , S. ( 2004 ), “ A review of instruments assessing creative and innovative environments within organizations ”, Creativity Research Journal , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 119 - 140 .

Mehmetoglu , M. and Jakobsen , T.G. ( 2017 ), Applied Statistics Using Stata: A Guide for the Social Sciences , Sage , London .

Miao , Q. , Newman , A. , Schwarz , G. and Cooper , B. ( 2018 ), “ How leadership and public service motivation enhance innovative behavior ”, Public Administration Review , Vol. 78 No. 1 , pp. 71 - 81 .

Mulgan , G. and Albury , D. ( 2003 ), Innovation in the Public Sector , Strategy Unit, Cabinet Office , London .

Orcutt , L.H. and AlKadri , M.Y. ( 2009 ), Barriers and Enablers of Innovation: A Pilot Survey of Transportation Professionals , CA PATH Program .

Patterson , M.G. , West , M.A. , Shackleton , V.J. , Dawson , J.F. , Lawthom , R. , Maitlis , S. , Robinson , D.L. and Wallace , A.M. ( 2005 ), “ Validating the organizational climate measure: links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 379 - 408 .

Potočnik , K. and Anderson , N. ( 2012 ), “ Assessing innovation: a 360-degree appraisal study ”, International Journal of Selection and Assessment , Vol. 20 No. 4 , pp. 497 - 509 .

Rego , A. , Sousa , F. , Marques , C. and Cunha , M.P. ( 2012 ), “ Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological Capital and creativity ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 65 No. 3 , pp. 429 - 437 .

Sanders , K. , Moorkamp , M. , Torka , N. , Groeneveld , S. and Groeneveld , C. ( 2010 ), “ How to support innovative behaviour? The role of LMX and satisfaction with HR practices ”, Technology and Investment , Vol. 1 No. 1 , pp. 59 - 68 .

Sarros , J.C. , Cooper , B.K. and Santora , J.C. ( 2008 ), “ Building a climate for innovation through transformational leadership and organizational culture ”, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies , Vol. 15 No. 2 , pp. 145 - 158 .

Schneider , B. , Ehrhart , M.G. and Macey , W.H. ( 2013 ), “ Organizational climate and culture ”, Annual Review of Psychology , Vol. 64 No. 1 , pp. 361 - 388 .

Scott , S.G. and Bruce , R.A. ( 1994 ), “ Determinants of innovative behavior: a path model of individual innovation in the workplace ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 37 No. 3 , pp. 580 - 607 .

Sexton , M. and Barrett , P. ( 2005 ), “ Performance-based building and innovation: balancing client and industry needs ”, Building Research and Information , Vol. 33 No. 2 , pp. 142 - 148 .

Shalley , C.E. , Gilson , L.L. and Blum , T.C. ( 2009 ), “ Interactive effects of growth need strength, work context, and job complexity on self-reported creative performance ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 52 No. 3 , pp. 489 - 505 .

Shalley , C.E. and Gilson , L.L. ( 2004 ), “ What leaders need to know: a review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity ”, The Leadership Quarterly , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 33 - 53 .

Shanker , R. , Bhanugopan , R. , van der Heijden , B.I.J.M. and Farrell , M. ( 2017 ), “ Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: the mediating effect of innovative work behavior ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 100 , pp. 67 - 77 .

Slåtten , T. ( 2011 ), “ Antecedents and effects of employees’ feelings of joy on employees’ innovative behaviour ”, International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 93 - 109 .

Slåtten , T. and Mehmetoglu , M. ( 2015 ), “ The effects of transformational leadership and perceived creativity on innovation behavior in the hospitality industry ”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 14 No. 2 , pp. 195 - 219 .

Sujan , H. , Weitz , B.A. and Kumar , N. ( 1994 ), “ Learning orientation, working smart, and effective selling ”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 39 - 52 .

Tan , C.S. , Lau , X.S. , Kung , Y.T. and Kailsan , R.A.L. ( 2019 ), “ Openness to experience enhances creativity: the mediating role of intrinsic motivation and the creative process engagement ”, The Journal of Creative Behavior , Vol. 53 No. 1 , pp. 109 - 119 .

Tierney , P. and Farmer , S.M. ( 2011 ), “ Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 96 No. 2 , pp. 277 - 293 .

Venturini , S. and Mehmetoglu , M. ( 2017 ), “ Plssem: a stata package for structural equation modeling with partial least squares ”, Journal of Statistical Software , Vol. 88 No. 8 , pp. 1 - 34 .

West , M.A. and Farr , J.L. ( 1989 ), “ Innovation at work: psychological perspectives ”, Social Behaviour , Vol. 4 , pp. 15 - 30 .

Windrum , P. and Koch , P.M. ( 2008 ), Innovation in Public Sector Services: Entrepreneurship, Creativity and Management , Edward Elgar Publishing , Cheltenham .

Xerri , M.J. and Brunetto , Y. ( 2013 ), “ Fostering innovative behaviour: the importance of employee commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 24 No. 16 , pp. 3163 - 3177 .

Yuan , F. and Woodman , R.W. ( 2010 ), “ Innovative behavior in the workplace: the role of performance and image outcome expectations ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 53 No. 2 , pp. 323 - 342 .

Zhou , J. and George , J.M. ( 2001 ), “ When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: encouraging the expression of voice ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 44 No. 4 , pp. 682 - 696 .

Zhou , J. and Shalley , C.E. ( 2003 ), “ Research on employee creativity: a critical review and directions for future research ”, in Martocchio , J. and Ferris , G.R. (Eds), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management , Elsevier , Oxford , pp. 165 - 217 .

Zhou , J. and Shalley , C.E. ( 2007 ), Handbook of Organizational Creativity , Psychology Press , New York, NY .

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, and to the participants for their willingness to take part in this research.

Corresponding author

Related articles, all feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

The influence of an integrative approach of empowerment on the creative performance for employees

In recent years, a notable amount of studies have focused on the significant effect of the creative performance of employees has on the overall effectiveness of organizations. Therefore, researchers and scholars have suggested different management practices that influence the creative performance of employees. In the same vein, this study reviewed literature relevant to various management practices that influence creative performance, specifically, employee empowerment approaches. The study discussed the nature of the three major approaches of empowerment that have been examined in the literature: empowering leadership, empowerment climate and psychological empowerment, and the influence of these approaches on the creative performance of employees. Accordingly, the researcher combined the three empowerment approaches, building a theoretical framework based on linking empowering leadership to creative performance through empowerment climate and psychological empowerment, in order to build an integrative approach to empowerment.

The researcher has distributed two different questionnaires to Jordanian banks in order to test the model of the study. One of the questionnaires has been designed to measure empowering leadership behaviors and practices, as well as measuring the empowerment climate and the psychological empowerment of employees in the Jordanian banking sector. The second questionnaire was designed to measure how managers perceive the creative performance of their employees. Accordingly, 500 matched questionnaires have been distributed to employees and their managers; 412 of these were matched and applicable for the analysis in the research.

Several exploratory factor analyses tests have been conducted to ensure the validity of the scales. The results have shown that all adopted scales were loaded according to the original scales and maintained their dimensions; however, some items have been eliminated from the scales due to cross loading. Overall, the results were consistent with those found in the empowerment and creativity literature.

Subsequently, correlation matrix tests were conducted between each new structural factor, in order to examine any possible relationship between an integrative approach of empowerment and creative performance. The results have supported all the hypotheses of the study. Afterwards, multiple regression tests were conducted to investigate the ability of an integrative approach of empowerment to predict the outcome of creative performance. The results have demonstrated that empowering leadership has a positive influence on both the empowerment climate and psychological empowerment. Similarly, the empowerment climate has a positive influence on psychological empowerment. Lastly, psychological empowerment has demonstrated a positive influence on creative performance.

Furthermore, mediation analysis was used to test the model; the results demonstrated that psychological empowerment and the empowerment climate completely mediate the relationship between empowering leadership and creative performance. To illustrate, empowering leadership has a direct and an indirect influence on creative performance; however, empowering leadership has a demonstrably greater effect on creative performance through an empowerment climate and psychological empowerment (Indirect Influence). According to these results and findings, the researcher has provided theoretical and practical implications and recommendations for future researchers to take into consideration as to the importance of an integrative approach of empowerment and its effects on the creative performance of employees.

Qualification level

Qualification name, publication year, usage metrics.

- Industrial and employee relations

Tell me what to do not how to do it: Influence of creativity goals and process goals on intrinsic motivation and creative performance

Previous research has identified creativity goals and process goals as two contextual interventions for enhancing creativity in the workplace. Whereas creativity goals direct attention and effort toward outcomes that are both novel and useful, process goals direct attention and effort toward the creative process – behaviors and cognitions intended to enhance creative outcomes. The current research draws from past research and theory on goals and intrinsic motivation to explain how creativity goals and process goals influence creative performance, and perhaps more importantly, why . Specifically, I suggest that creativity goals have a direct, positive relationship with creative performance; however, process goals have an indirect, positive relationship with creative performance through creative process engagement. Additionally, specificity has the ability to focus attention on relevant processes and outcomes within the creativity criterion space. While specific creativity goals are predicted to direct attention toward desirable solutions without thwarting needs for autonomy, specific (i.e., structured) process goals may thwart autonomy perceptions, resulting in lower levels of intrinsic motivation, and ultimately creative performance. The hypotheses proposed were examined in a sample of 560 undergraduate students utilizing a 3 (creativity goals: specific, general, and no goal) x 3 (process goals: structured, semi-structured, and no goals) between-subjects experimental design. Results revealed creativity goals, particularly specific creativity goals, have a direct positive influence on creative performance. Process goals have an indirect positive relationship on creative performance through creative process engagement. Moreover, process goals have a negative impact on perceptions of autonomy, which in turn negatively impacts creative performance by reducing intrinsic motivation. The specific creativity goal had the strongest effects and appears to be an effective way to enhance both creative process engagement and creative performance. Taken together, these findings suggest that goals are a tenable means of enhancing creative performance; however, care should be taken to reduce adverse consequences for autonomy perceptions.

Degree Type

- Doctor of Philosophy

- Psychological Sciences

Campus location

Advisor/Supervisor/Committee Chair

Additional committee member 2, additional committee member 3, additional committee member 4, usage metrics.

- Industrial and organisational psychology (incl. human factors)

- Behavioural neuroscience

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Beliefs about creativity influence creative performance: the mediation effects of flexibility and positive affect.

- School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

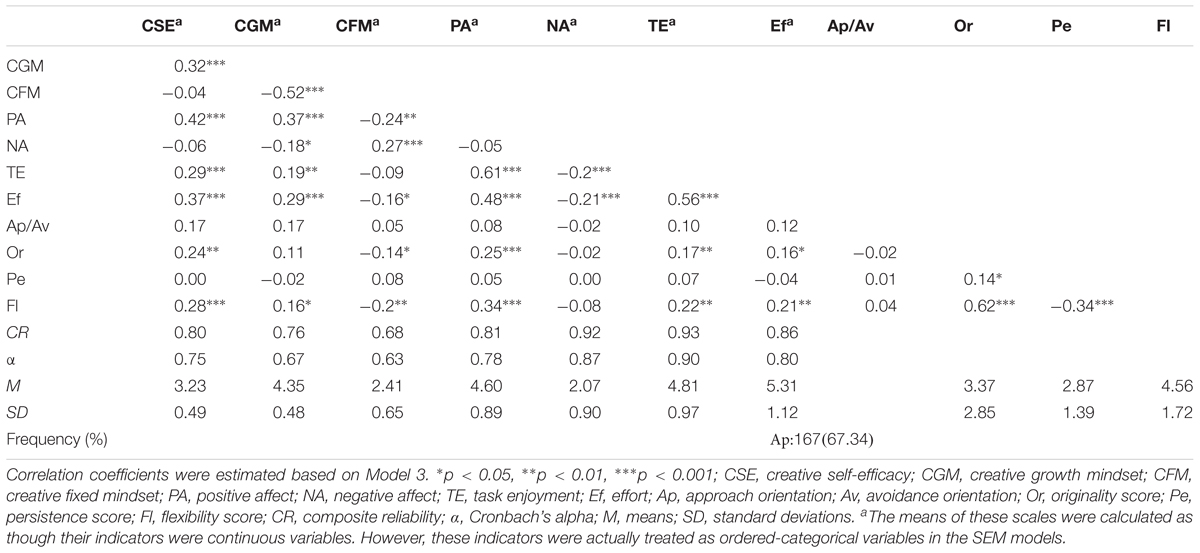

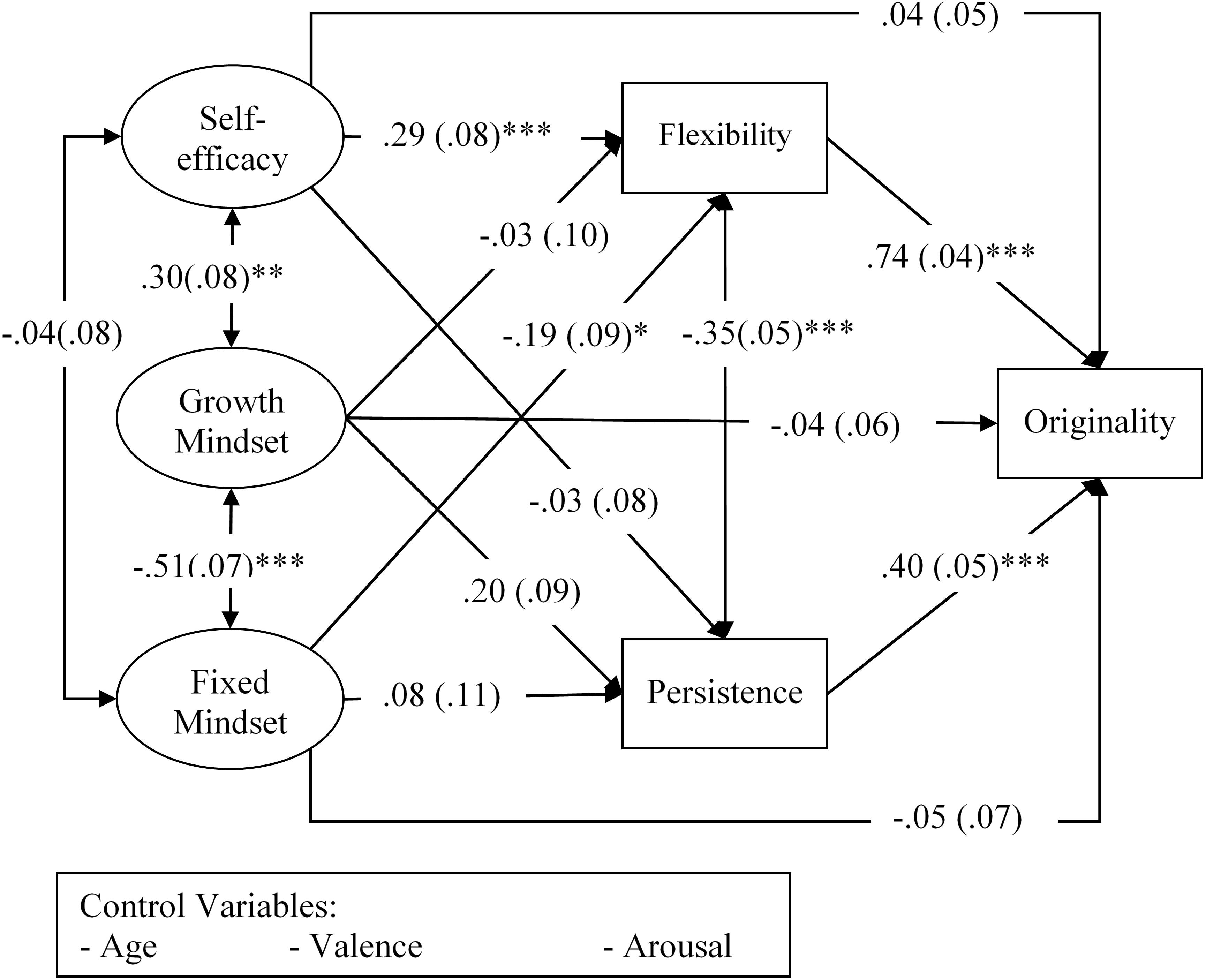

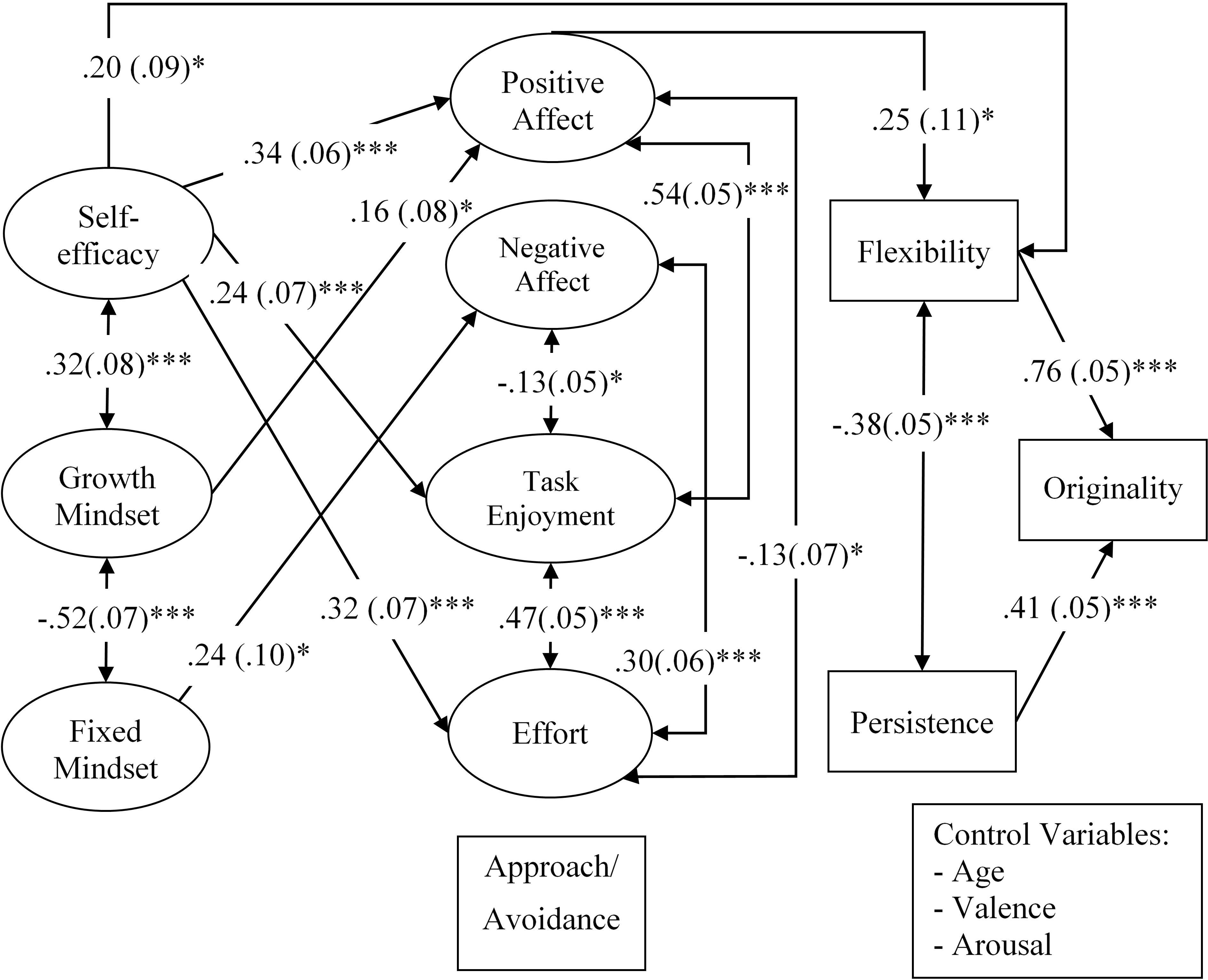

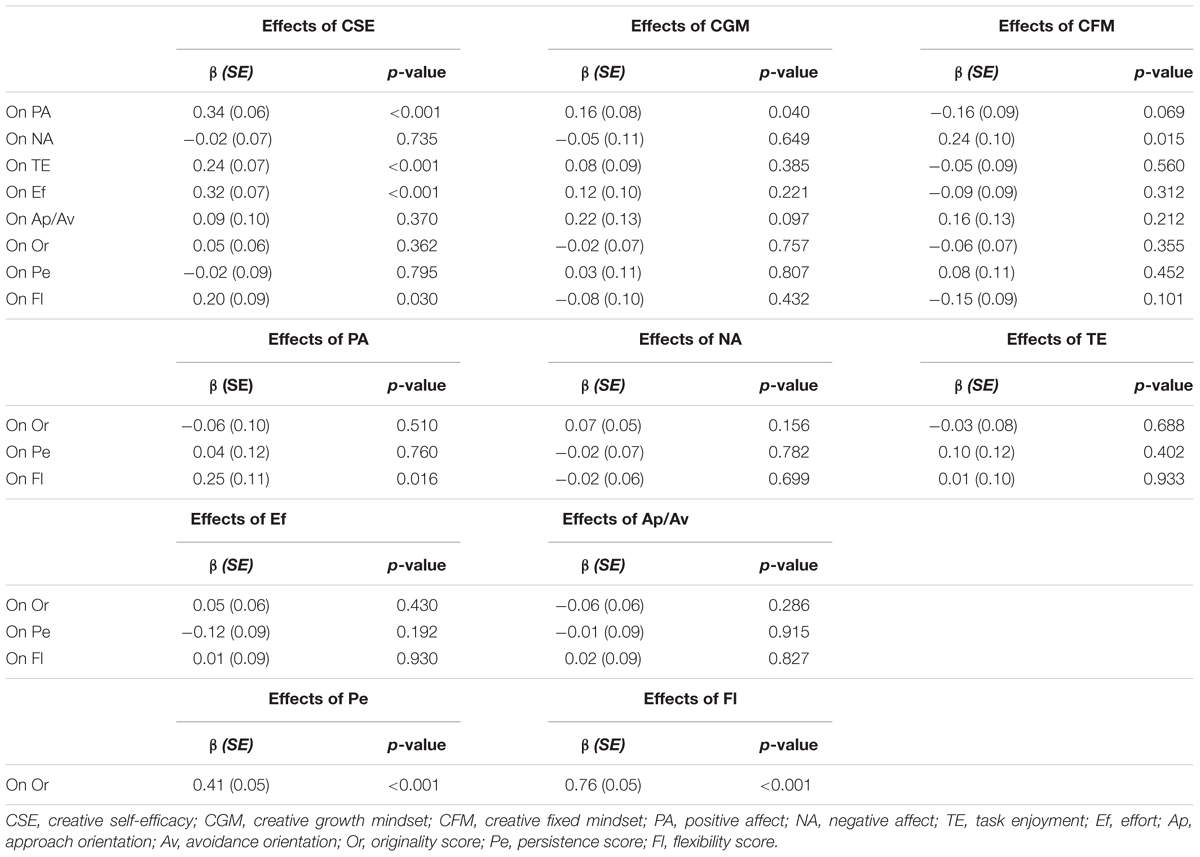

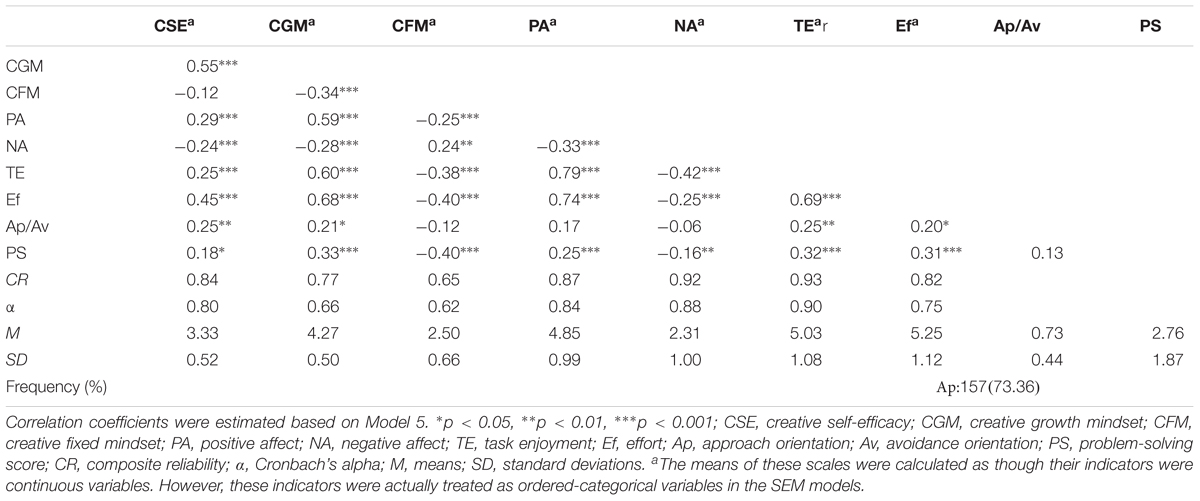

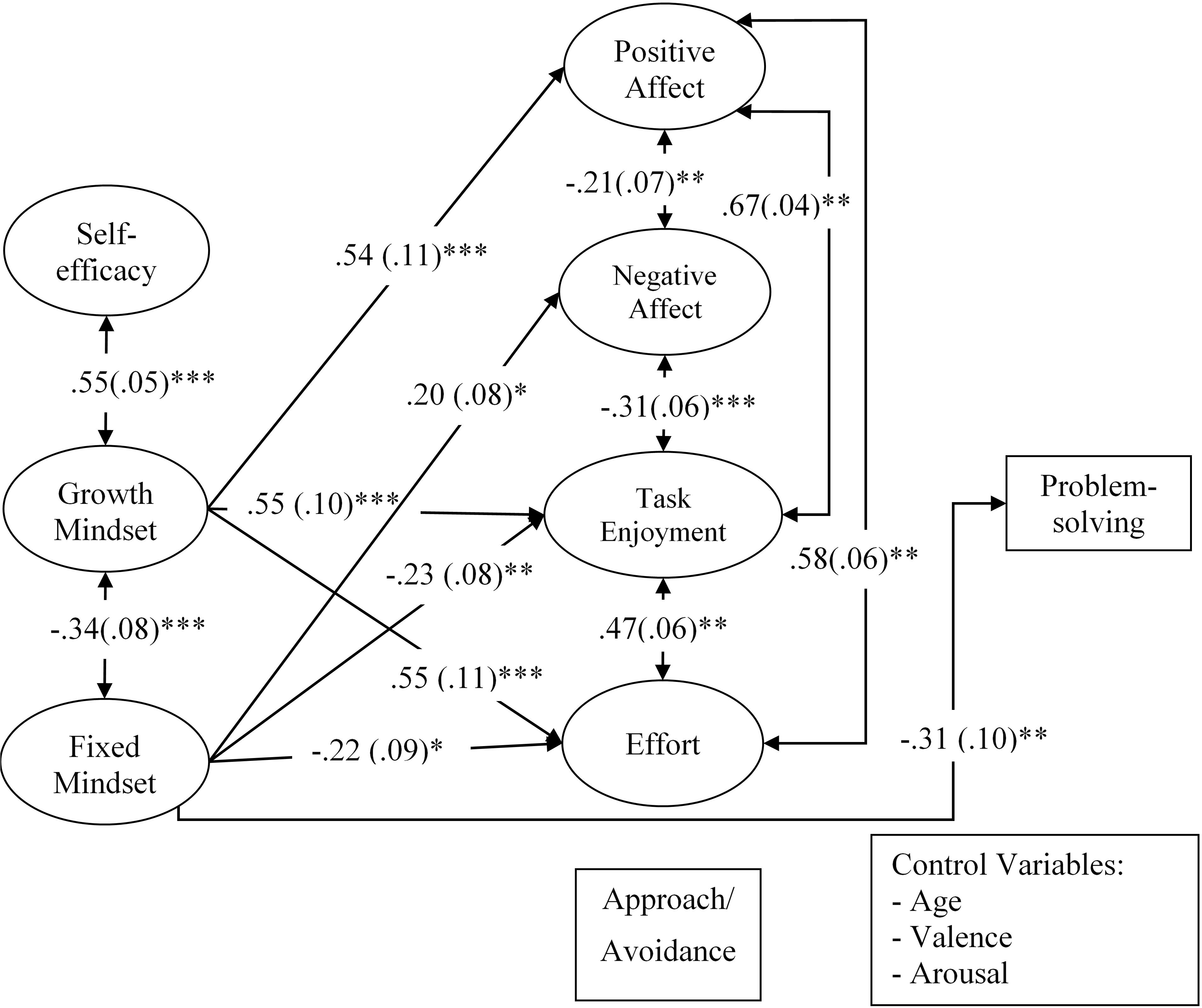

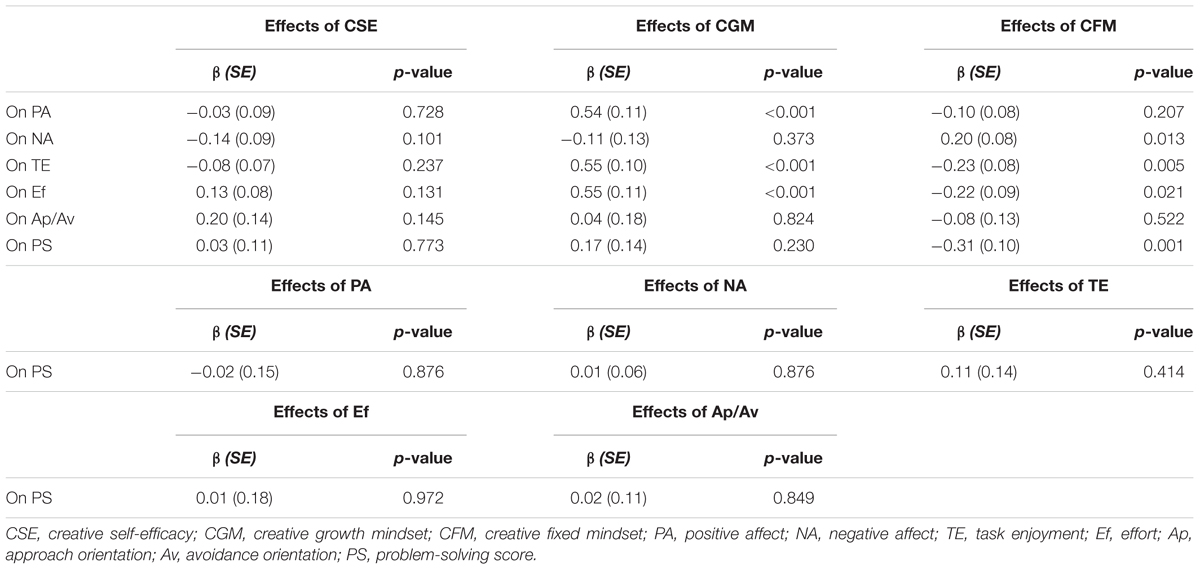

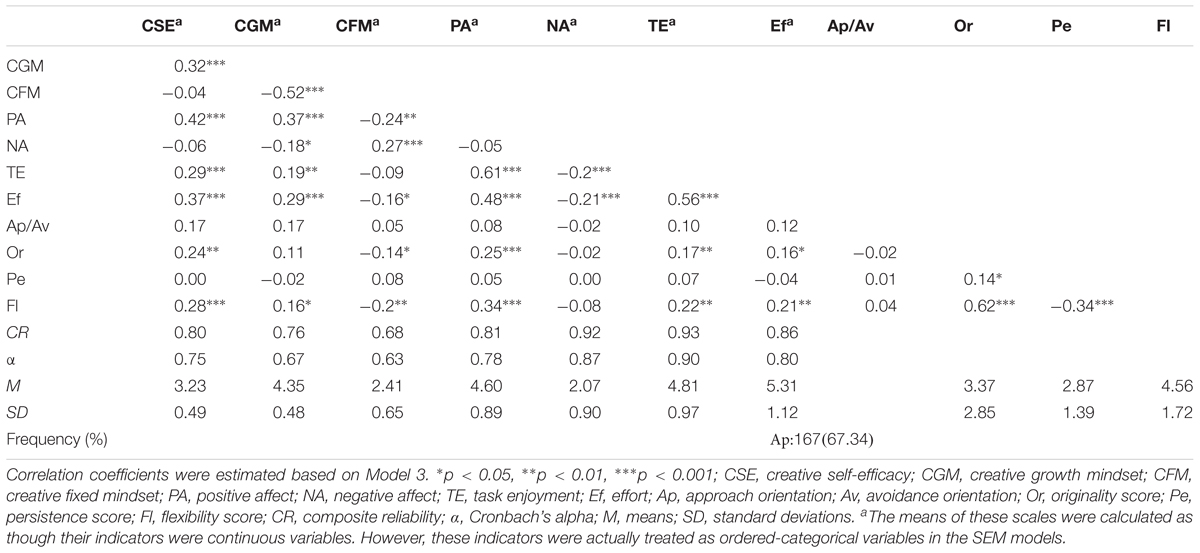

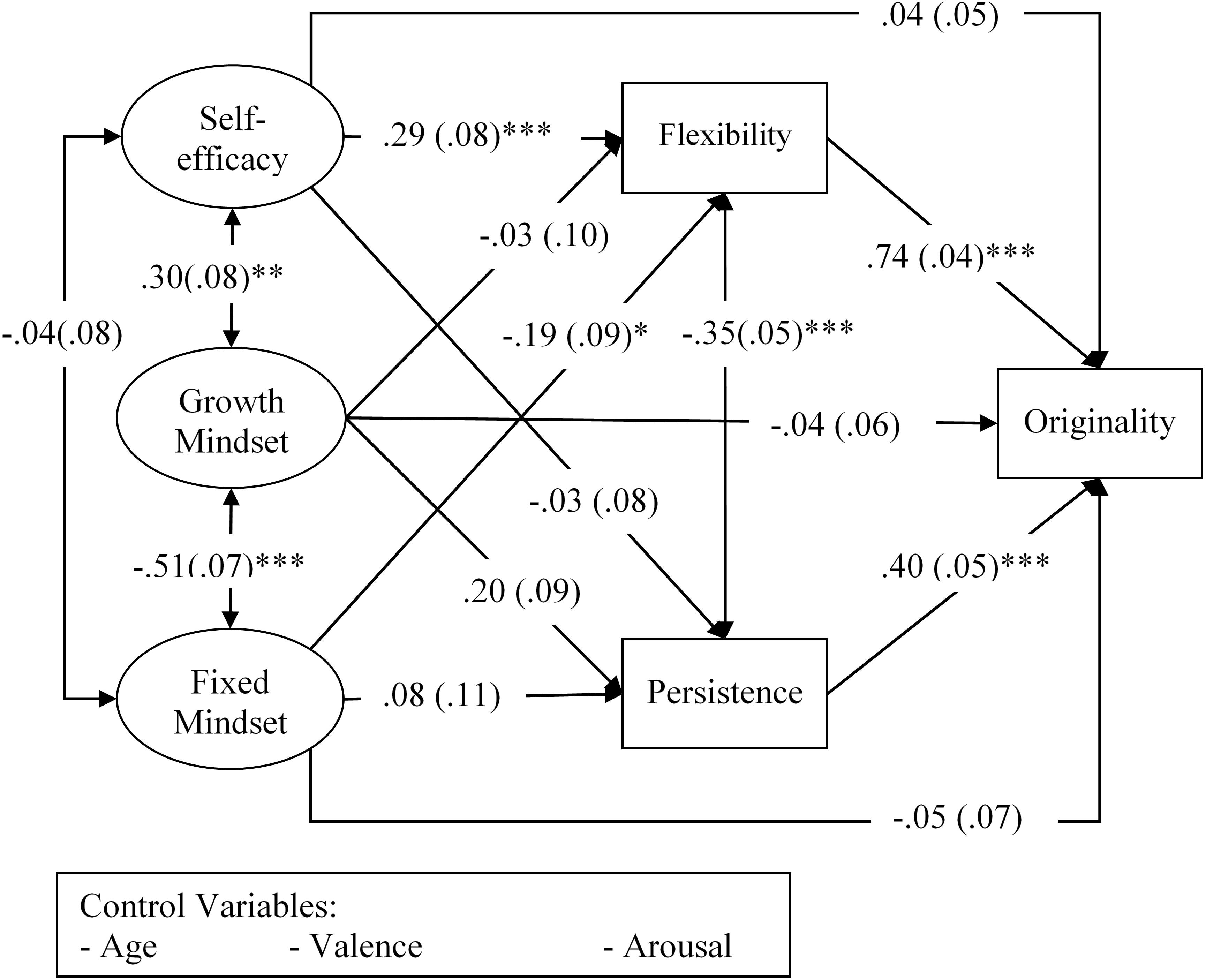

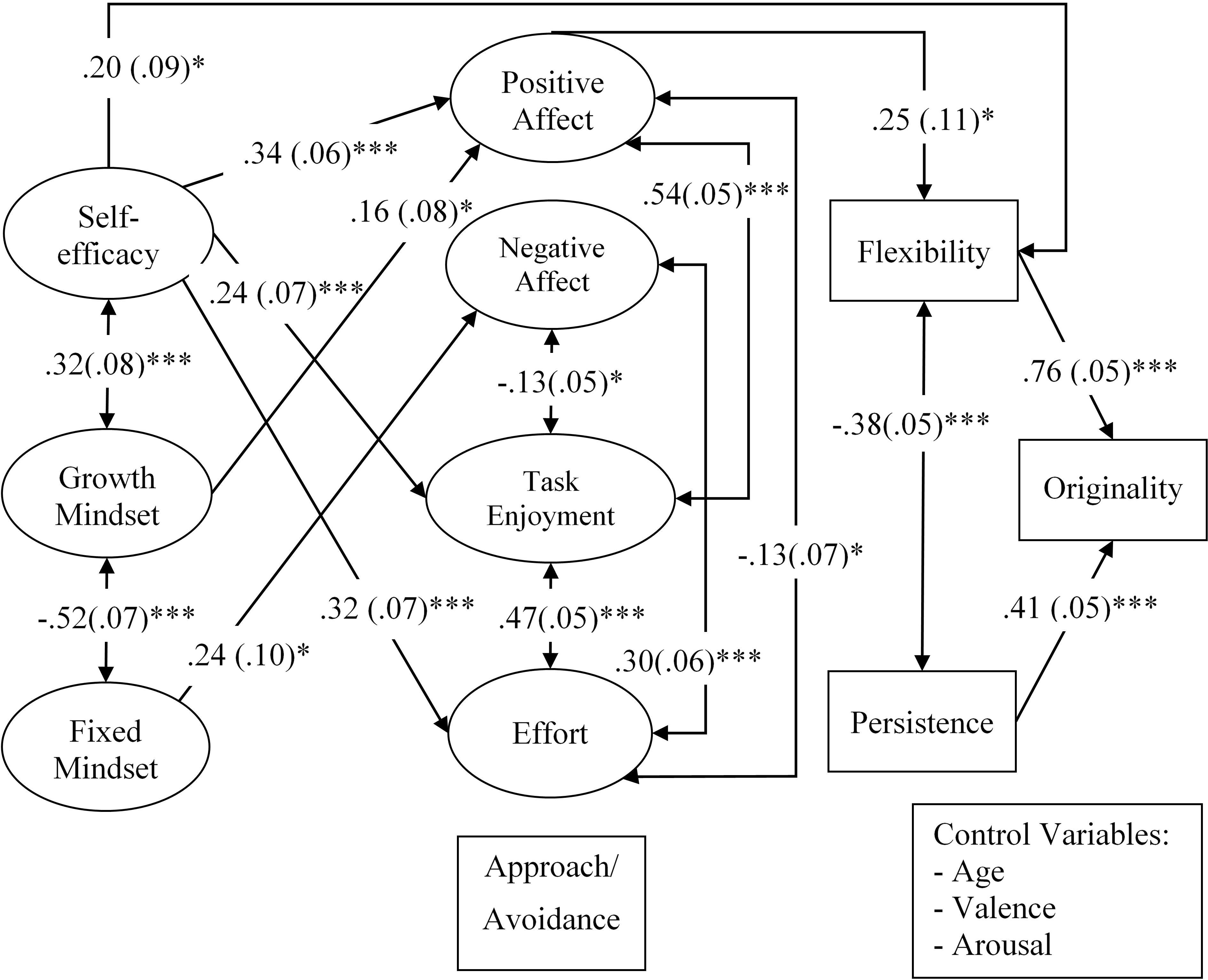

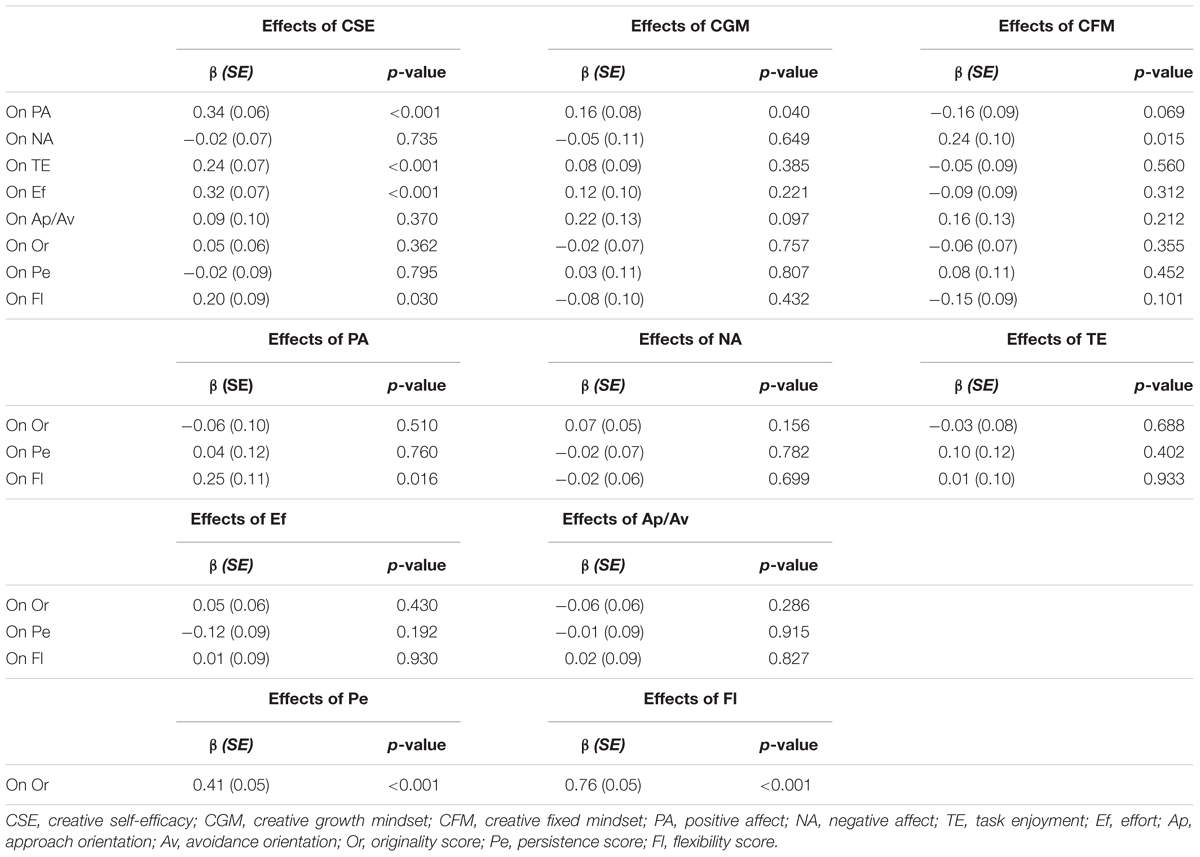

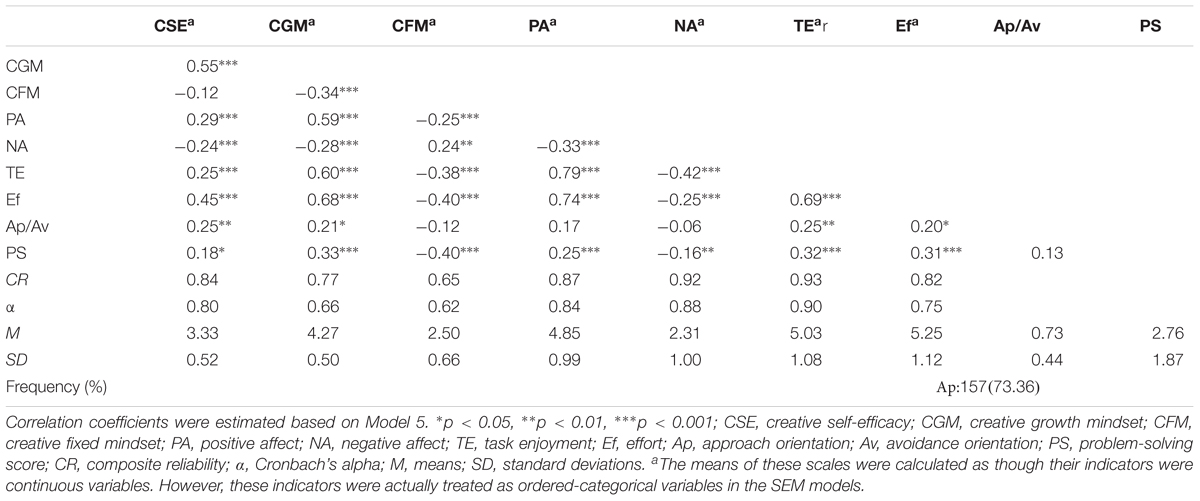

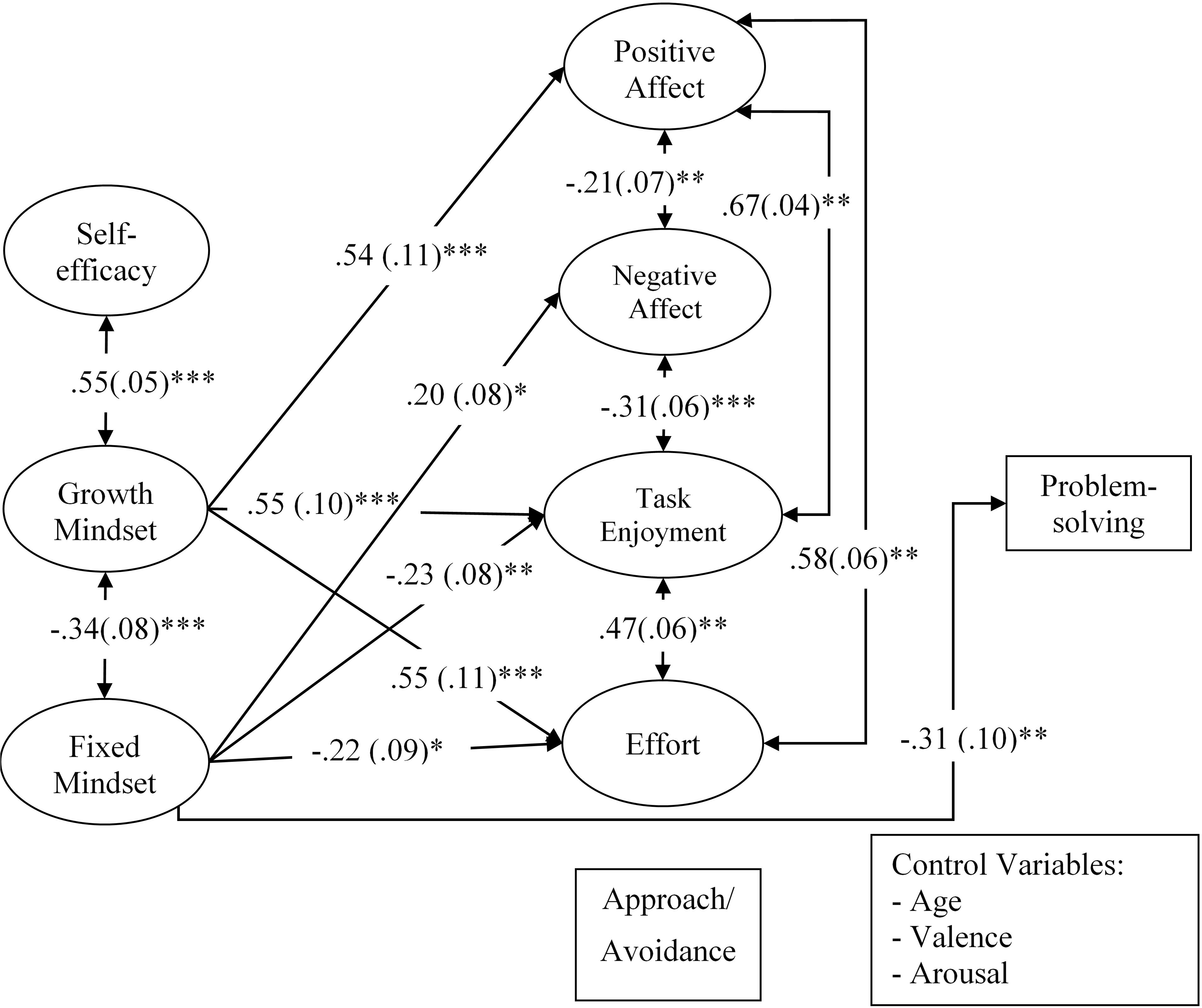

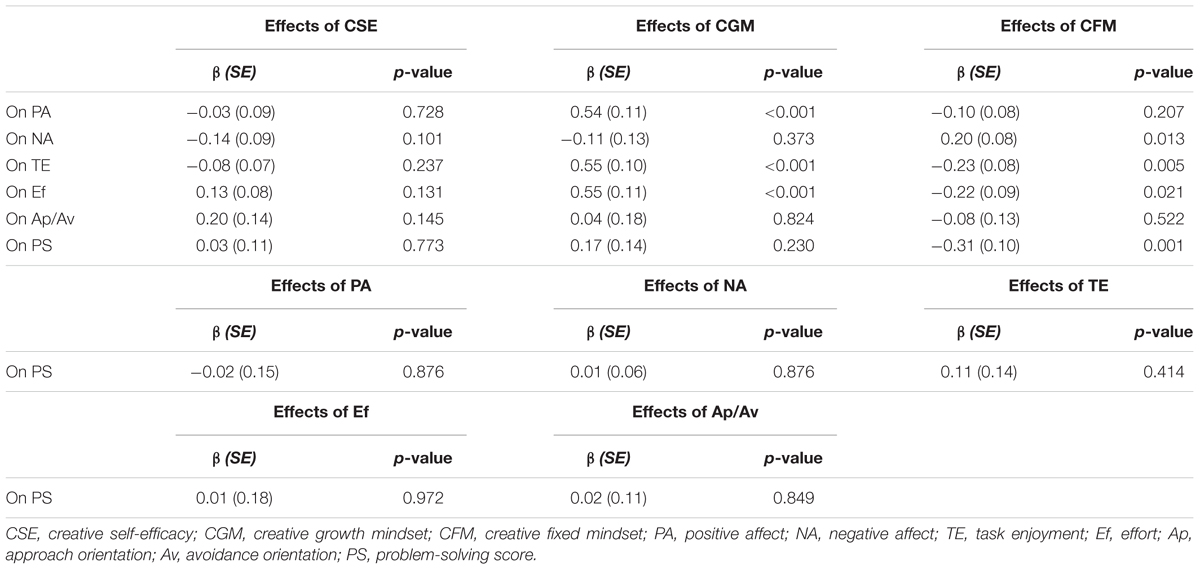

This research explores potential factors that may influence the relationship between beliefs about creativity and creative performance. In Study 1, participants ( N = 248) recruited from upper secondary schools in Thailand were asked to solve the Alternative Uses Task (a typical divergent thinking task) and complete a series of questionnaires concerning individual beliefs about creativity and potential factors of interest. The results of structural equation modeling reveal a mediation effect of flexibility on the relationship between self-efficacy and originality. The path from self-efficacy to flexibility was also partially mediated by positive affect. Self-efficacy was also positively correlated with task enjoyment and effort. Additionally, the growth mindset was positively associated with positive affect, while the fixed mindset was positively related to negative affect. In Study 2, participants ( N = 214) were asked to solve the Insight Problems Task (a typical convergent thinking task). The results indicate that the growth mindset was positively related to task enjoyment, effort, and positive affect. The fixed mindset was negatively related to task enjoyment, effort, and creative performance. A positive relationship between the fixed mindset and negative affect was also observed. Taken together, these findings unveil some potential factors that mediate the relationships between beliefs about creativity and creative performance, which may be specific to divergent thinking tasks.

Introduction

Creativity and beliefs about creativity.

Psychologists agree upon the definition of creativity as the ability to produce work that is novel (original and unique) and useful ( Stein, 1953 ; Sternberg and Lubart, 1993 ; Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ). From a cognitive perspective, creativity is concerned with two types of thinking, namely divergent thinking and convergent thinking, both of which lead to creative production ( Cropley, 2006 ). Divergent thinking involves searching through various directions, and multiple solutions to a problem are generated; in convergent thinking, thought is directed to one correct or best solution ( Guilford, 1956 , 1959 ).

Despite the growing number of studies done on creativity, there is still much to be learned ( Runco and Albert, 2010 ). Throughout the years, researchers have studied creativity from various perspectives, including how individuals’ beliefs influence creativity. The topic of beliefs about creativity has been approached from different angles such as how people view themselves (i.e., creative self-beliefs) and how people perceive the nature of creativity. In this paper, we focuses on creative self-efficacy which is one of the key self-beliefs, and beliefs about the malleable nature of creativity (i.e., creative mindsets) which have attracted more researchers recently.

Creative self-efficacy is the belief that one can produce creative outcomes ( Tierney and Farmer, 2002 ). As in most fields, research on creative self-efficacy has been grounded in Bandura’s (1977) work on self-efficacy beliefs. Within this framework, self-efficacy beliefs determine how efficient people function through cognitive, motivational, affective, and decisional processes ( Bandura, 1993 , 2011 ). Self-beliefs of efficacy influence how much effort people put into a task, how persistent they are, and what task choices they prefer ( Bandura, 1977 ; Zimmerman, 2000b ; Schunk and DiBenedetto, 2016 ). When facing a challenge, people gauge their capacity to keep themselves motivated, focus on the task at hand, and manage negative thoughts and feelings ( Bandura and Locke, 2003 ). Self-efficacy and performance mutually influence each other ( Bandura, 1989 ; Williams and Williams, 2010 ). Past experiences shape people’s current beliefs and their current beliefs drive their future actions.

Previous research has revealed evidence of the association between creative self-efficacy and creativity as assessed by various measures. For instance, in organizational settings, Michael et al. (2011) found that employees’ creative self-efficacy was positively related to their self-reported innovative behaviors. Studies by Tierney and Farmer (2002 , 2011 ) also demonstrated that employees with high levels of creative self-efficacy tended to be rated with high levels of creativity by their supervisors as well. In school contexts, Beghetto et al. (2011) investigated elementary school students’ self-efficacy in creativity and found more self-efficacious students were given higher ratings of creative expression by their teachers. Karwowski (2011) studied high school and gymnasia students’ creative self-efficacy. Using an unfinished, framed drawing task as a measure of divergent thinking, Karwowski also found a positive link between students’ self-efficacy and their performance of the task. Based on prior research, the connection between creative self-efficacy and creativity is quite promising.

Unlike creative self-efficacy, creative mindsets are not self-beliefs but rather implicit theories concerning the source and nature of creativity ( Karwowski and Brzeski, 2017 ). The work of Dweck and her colleagues on malleability beliefs has guided research on creative mindsets (e.g., Dweck and Leggett, 1988 ; Mueller and Dweck, 1998 ; Hong et al., 1999 ). According to their research, it makes a difference whether people believe that a certain attribute is fixed or unchangeable (fixed beliefs) or that a certain attribute is developable through hard work (incremental beliefs). When engaging in a task, people with fixed beliefs attribute their success or failure to the presence or lack of ability; conversely, people with incremental beliefs ascribe the task outcome to effort ( Hong et al., 1999 ; Haimovitz and Dweck, 2017 ). As such, holding incremental beliefs is linked to desirable behaviors such as persistence, adoption of adaptive goals, and resilience in the face of setbacks ( Mueller and Dweck, 1998 ; Yeager and Dweck, 2012 ). Holding fixed beliefs, on the other hand, is related to maladaptive behaviors such as learned helplessness ( Hong et al., 1999 ). Compared to fixed beliefs, therefore, incremental beliefs lead to achievement in the long term ( Blackwell et al., 2007 ). Dweck (2006) has introduced the terms “growth mindsets” and “fixed mindsets.” People with incremental beliefs endorse a growth mindset, while people with fixed beliefs endorse a fixed mindset. In this paper, the term “creative mindsets” is used to refer to beliefs concerning the malleable nature of creativity.

The concept of creative mindsets is relatively new. As a result, the connections between creative mindsets and creativity have been explored less than creative self-efficacy has. O’Connor et al. (2013) conducted a series of studies to examine creative mindsets and creativity. Using their self-developed scale, they found that the creative growth mindset positively predicted interest in creative thinking, creative performance as assessed by the Unusual Uses Task (also known as the Alternative Uses Task), self-reported creativity (Study 1), and prior creative achievements across various domains (Study 2). Manipulation of creative mindsets (Study 3) also demonstrated that participants in the growth-mindset-induced group performed better in the Unusual Uses Task. This study provided evidence that creative mindsets affect creative performance. Karwowski (2014) developed a scale to measure creative mindsets and examined their relations to creative problem-solving as measured by insight problems. He found that the fixed mindset was related to inefficient problem-solving performance.