TWO WRITING TEACHERS

A meeting place for a world of reflective writers.

“I Feel Like a Real Writer:” Supporting Gifted Students in Writing

“Lucky you! You’ve got gifted kids.They GET IT.”

You’d think working with gifted students would be a smooth, easy road, like those highways in Nevada whose view is unbroken by anything but horizon.

Let’s get real. Our road has speed bumps – plenty of them. If I had my way, gifted education would be a part of the special education spectrum. That, however, is a different soapbox for a different day.

We can, however, dispel a key myth. Not all gifted readers are strong writers. Even kids who are great with words are plagued by any number of factors. Some wrestle the many-headed hydra of perfectionism. Others have an abundance of ideas but no clear strategies for wrangling those thoughts into writing. Still others are victims of impostor syndrome, wrongly comparing themselves to others and continually falling short. Writing instruction for gifted students is as affective as it is skill-based.

We had another obstacle, a familiar one: COVID. No longer was I able to work right alongside my “loveies.” Despite our district being in-person since August, I was required to hold classes via Zoom to keep classroom “bubbles” intact.

If we wanted a writing community, we’d have to move beyond flair pens, clipboards, fancy paper, and flexible seating. We’d need a safe place to share writing, where students could gather articulate feedback, and learn the joy of cultivating a responsive, positive readership. Where kids see themselves as writers and enjoy the craft of it.

In short, I wanted what I had through the Slice of Life community: Joy. Love of craft. Validation.

Opening the Gates: Establishing Safety and Community

As a class, our first order of business was to create the time and space to craft in the modes and genres we loved most. At the end of each day, students posted screenshots or photos of a passage they felt proud to have written that day, and complemented at least three other writers.

Like cats coaxed from under the bed, most grew more comfortable composing. Once I had them writing, I wanted kids to feel the pride of having others read and appreciate their work.

I started with home-grown mentor text: the comment section on my own blog. We identified types of feedback to share: compliments, encouragement, connections, quotes from text, and literary analysis. They did not disappoint.

We had one hard and fast rule: no critique (yet).

Of course kids wanted to make suggestions. (Did I mention that many gifted students feel strongly about “right” ways to do things?) I steered them in a different direction, once again using Slice of Life as the example.

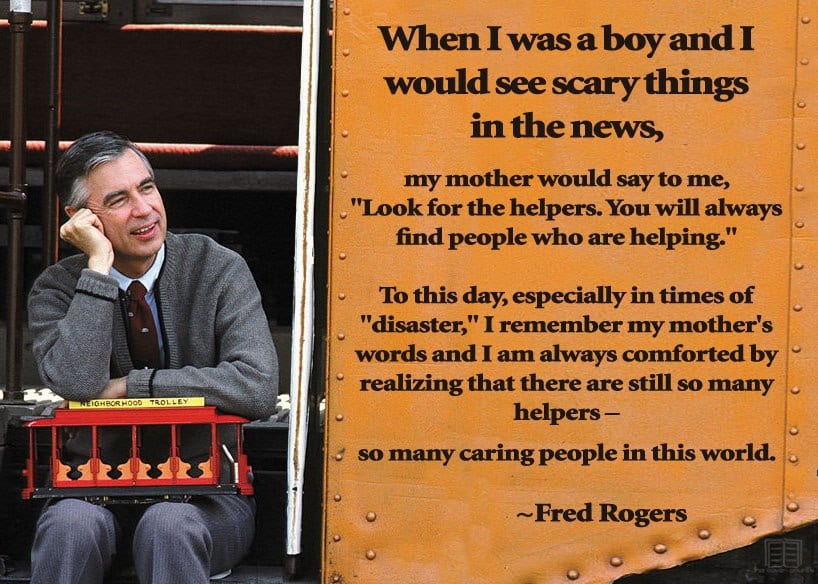

Consider: In our blogging community, how often do readers leave unsolicited advice or suggestions? Just about…never. We trust one another as writers, which allows us to trust OURSELVES as writers.

Slowly but surely my kids realized they were writing for a genuine audience of peers. I couldn’t ask for more.

Well…perhaps I could.

Revision: The Elephant in the Room

“If no one offers corrections, how can students improve their work?”

I can’t get around it: students need to develop writing skills. Even some of the most talented writers still have hair-graying spelling and conventions.

I started with a self-paced “Fiction Dojo” on the Schoology app. Kids “leveled up” by revising or editing a single area such as capitalization, dialogue, or balance of narration. Students needing support worked with me in breakout rooms.

I learned quickly the “Dojo” system didn’t translate exactly as hoped. Not every student needed to review every single level, and some needed to complete “belts” out of order in the interest of sense-making.

It was the universe’s sneaky way of reminding me to TRUST my WRITERS. After each revision, students often asked what they “should do next.” Sometimes I gave that guidance, but mostly I said, “I trust your judgment. What do you think your readers need from you?”

What happened, in turn, was the crafting of stories that were more strongly edited and revised than I ever could have accomplished through individual conferencing and assignments.

As for building critique back in, I’ll confess I’ve never had much luck with peer conferences. My kids have a tough time directing that conversation regardless of structure. No chart or questionnaire has ever fit.

And then it hit me. CROWDSOURCING.

What wisdom from the “hive mind” did they need? A title? Character names? Help making a scene better or more readable? Putting these questions in the hands of WRITERS, seeking feedback from READERS, made the most sense.

Friends, it was magic. Writers trusted themselves to know what they needed help with, and they trusted their peers enough to support without judgment.

Looking Ahead

I think I’m onto something here. Even my most reluctant writers have more confidence and joy in writing than I’ve ever seen. Throughout the coming weeks and into next year, I’m looking for ways to strengthen self-efficacy and community through shared reading and feedback.

Our next area of exploration follows a “what-if.” What if we use STUDENT writing as mentor text? What if we use students’ writing as a basis for book clubs, for literary analysis? Would that encourage students to further develop their craft? Would it engage them more deeply in reading and conversations about text? My intuition says yes, and I’m anxious to learn more. In a perfect world, I would farm this strategy out to my mainstream classroom colleagues.

Now, there are still places where my lovies fall short on their writing rubrics. I’ve learned I can’t control all of their conversation or revisions. I’ve discovered there are still places I’d love kids to “get to,” but that’s not my journey.

Sometimes their cars are on that Nevada highway, driving somewhere I never would have imagined, and that destination is quite fabulous.

I’m just glad to be along for the ride.

Share this:

Published by Lainie Levin

Mom of two, full-time teacher, wife, daughter, sister, friend, and holder of a very full plate View all posts by Lainie Levin

7 thoughts on “ “I Feel Like a Real Writer:” Supporting Gifted Students in Writing ”

I cannot wait for next year to start to try all this out! I can only imagine, though, how much planning and ‘inner thinking’ must’ve gone into this! STUPENDOUS! 👏🏼

Thank you! It’s the result of a lot of evolution as a teacher of writing. What’s exciting to me is knowing how much FURTHER we can go!

I remember your posts on “crowdsourcing” and its effects, all stemming from putting writers in the driver’s seat and fostering trust. Invaluable! This collective magic – transformational. That community-building, that sense of belonging – priceless. I also recognize so many truths here regarding the “myths” and what I love best is seeing a teacher stopping to consider what her students really need and thinking out of the box about how to make this happen. No “oh wells” or “I don’t know hows” or “things are MOSTLY ok, so…” but how can I get them where they need to be (any student, all students, for all have gifts) and to love the learning journey. It is an evolutional journey for the teacher as well – try and try again, asking “more” of students AND self. So well-done. I sense your own joy as well as theirs, Lainie. It’s something we all need more of in education – for if teaching is a chore, so will the learning be. Just – bravo!

Like Liked by 1 person

Thank you, Fran! It’s weird, because even though I can acknowledge how far we come, it only makes me realize how much further we CAN go together. As for the stopping to consider my kids, I’m glad we worked so hard to develop community. In years like these, where there is so much NOISE coming at educators, from every direction, the children are always the one to make things worthwhile. They saved me this year, as they’ve done so often in the past. You also make an important point about how teaching and learning should be a joy rather than a chore. A colleague and I were just having that conversation yesterday – that we should ALL be in touch with the things we’re passionate about learning. If we don’t have those things, well…maybe we’re not in the right place. Thanks for your thoughtful feedback, Fran.

Lainie, thank you for a thought-provoking post. As I was reading this, I found myself nodding along and saying, “yes” more than once. I really appreciate how you used the SOL community as a model for what you wanted in your classroom. As I move into a classroom next year after four years out, I’ve been thinking about how I wanted to do the same thing. Your ideas on bringing others into the conversation regarding editing and revising are a definite help as I put together my own plans. Thank you!

Tim, that’s exactly what I hope to do in posts like these – to get readers to nod along and say “Yes!” “Exactly!” It’s my goal to get folks riled up so they’ll want to take an action (little or big) in whatever direction they feel so moved. And Tim, I can’t help but think how lucky your kids are going to be to have you FULL TIME. You get to take those children under your wing, and THAT will be a wonderful thing for this world.

Well, consider me riled! When I think back to the early years of my teaching career, it was books (good books!) that I looked to for inspiration and direction when it came to developing writers. It’s great — beyond great — to have this community and the experience it shares. Thanks for being a part of it!

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Our Mission

Identifying and Nourishing Gifted Students

Let’s broaden our definition of gifted students to include creativity, writing skills, musical and artistic talent, superior leadership and speaking skills, and moral character.

Having just seen He Named Me Malala , a film about the life and work of teenage Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai, I wonder whether this young woman, gifted in thinking, values, courage, and public speaking, would ever have been selected for a gifted program in a U.S. school. In the film, she notes that her performance in some of her academic subjects is not that good. A few days earlier, I'd received the book Failing Our Brightest Kids by Chester Finn, Jr. and Brandon Wright, a critique of how we're failing our best students. Carefully skimming the book and the index, I saw only one mention of the arts and some musings about whether considering giftedness and talent adds to or "muddies" the authors' topic. Perhaps more muddying is needed!

Discussions of the best and brightest seem to invariably focus on kids who score high in math and language testing, and some who also demonstrate high scientific aptitude. I agree that we need to do a better job of identifying these kids and nourishing the development of their abilities.

But we should also discuss how we all too often fail others of our most gifted and talented students and how this begins with our very limited definition of gifted and bright . Because of this narrow definition, we fail many of our most gifted kids at a significant cost to the students themselves -- and to us as a nation.

Defining, Identifying, and Nourishing Gifted Students

How do we define gifted? How do we identify gifted students? How do we nourish these talents in our schools and classrooms?

Our current definitions, usually limited to verbal and math test scores and/or IQ, exclude students who missed the cutoff point on tests. A student might be a highly gifted writer or extraordinary social analyst and have great moral character, but he or she might be a mediocre test taker.

In my ideal school, giftedness would include any of the following:

Ask Edutopia AI BETA

This is step one for both school districts and teachers, who should be committed to identifying important talents ignored in our normative focus on high test scores. And I strongly believe that the qualities of moral courage and public speaking skills demonstrated by someone like Malala should be on that list.

Part of the problem relates to the second question: How do we identify gifted students? We are stuck in a paradigm in which we allow what is most easily measured to define our focus. The tail wags the dog. Testing easily identifies verbal and mathematical skills and memorization. When we move into other areas, we find it more challenging to come up with methods of identifying talent. Yet it isn't difficult for music and art experts to identify talent in their fields. Leadership ability is evident in classes and schools. While identifying moral talent is more value laden, there are individuals, even short of Malala's gifts, who demonstrate their moral courage in our classrooms and schools, or their volunteer work outside of school. We need to work on better identification methods, rather than excluding talent that isn't easy to measure.

A recent NPR piece speaks well to the subject of how we can identify and nourish gifted students in every school and classroom .

The Role of Teachers, Parents, and Schools

Sharing information about student talents should be a critical part of the process. Teachers from different disciplines and the arts must combine their impressions of students for a fuller picture of their talents. Parent input should be actively sought. Many parents know of their children's exceptional talents that could go unnoticed in a school setting.

Teacher observational skills can be improved in identifying exceptional leadership ability and moral courage. In social studies and English classes, students should be given the opportunity to write about social issues and do presentations of learning that demonstrate their public speaking ability. There are many kids who may not write perfect essays, but who demonstrate extraordinary articulateness when addressing a group.

Who is that student who frequently speaks up with a strong, positive, moral position on some issue related to racial prejudice, sex-related discrimination, immigration policies, or climate control? Is this not a gift that our society needs?

Schools should provide multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their talents and receive mentoring to further develop them.

One example is presentations of learning that utilize artistic and musical talent as a means of communication. I observed such a presentation at Eagle Rock School in which a musically gifted student played his guitar and sang a song he'd written about his learning experiences during that trimester. That's way outside our usual educational frame, and that's my point. We have to move beyond that frame if we expect to nourish and help strengthen our most gifted students.

Science appears to be an easier area, because many schools provide opportunities for students to develop science projects that can be entered in local and even national competitions.

Identifying and Nourishing Morally Gifted Leaders

When it comes to leadership, there have been very gifted leaders who were also destructive. Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez were gifted, but so were Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler. So students gifted as leaders need special attention to determine whether their moral values could be challenged or better developed, or if they already have a commitment to positive social change.

If you share my commitment to also identifying gifted children with great moral sensitivity, and nourishing those talents, I highly recommend reading Identity Development in Gifted Children: Moral Sensitivity and The Moral Sensitivity of Gifted Children and the Evolution of Society , both from the educational non-profit Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted. You should also take a look at Ben Johnson's Edutopia post, How to Support Gifted Students in Your Classroom .

Including All Students

Another NPR piece brought up the issue of how our Latino and black children are most frequently lost in the process . It should be no surprise that when the criteria for gifted focus on test scores, Latino, black, and immigrant kids would be the most shortchanged.

Finally, I just saw this story about an incredible 17-year-old woman who started The National Youth Orchestra of Iraq . She did this in the midst of the war and was recently named Visionary of the Year by the Euphrates Institute.

Would Zulan Sultan have been selected for a gifted program? Would she have scored well on our tests that are used to determine the best and brightest? Very possibly not. That needs to change.

How to identify, understand and teach gifted children

Professor, Faculty of Education and Arts, Australian Catholic University

Disclosure statement

John Munro has been a chief researcher on ARC funded projects and has completed contracted projects for Australian educational authorities.

Australian Catholic University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This is a longer read at just under 2,000 words. Enjoy!

The beginning of the 2019 school year will be a time of planning and crystal-gazing. Teachers will plan their instructional agenda in a general way. Students will think about another year at school. Parents will reflect on how their children might progress this year.

One group of students who will probably attract less attention are the gifted learners . These students have a capacity for talent, creativity and innovative ideas. They could be our future Einsteins.

They will do this only if we support them to learn in an appropriate way. And yet, there is less likely to be explicit planning and provision throughout 2019 to support these students. They’re more likely to be overlooked or even ignored.

Giftedness in the media

You may have noticed the recent interest in gifted learning and education in the media. Child Genius on SBS provided a glimpse of what the brains of some young students can do.

We can only marvel at their ability to store large amounts of information in memory, spell words correctly they’d probably not heard before and unscramble complex anagrams.

The Insight program on SBS, provided another perspective.

Students identified as gifted explained how they learned and their experiences with formal education. Most accounts pointed to a clear mismatch between how they preferred to learn and how they were taught.

Twice exceptional

The students on the Insight program showed the flipsides of the gifted education story. While some gifted students show high academic success – the academically gifted students, others show lower academic success – the “ twice exceptional ” students.

Many of the most creative people this world has known are twice exceptional . This includes scientists such as Einstein, artists such as Van Gogh, authors such as Agatha Christie and politicians such as Winston Churchill.

Read more: Intellectually gifted students often have learning disabilities

Their achievements are one reason we’re interested in gifted learning. They have the potential to contribute significantly to our world and change how we live. They’re innovators. They give us the big ideas, possibilities and options. We describe their achievements, discoveries and creations as “talent”.

These talented outcomes are not random, lucky or accidental. Instead, they come from particular ways of knowing their world and thinking about it. A talented footballer sees moves and possibilities their opponents don’t see. They think, plan, and act differently. What they do is more than what the coach has trained them to do.

Understanding gifted learning

One way of understanding gifted learning is to unpack how people respond to new information. Let me first share two anecdotes.

A year three class was learning about beetles. We turned over a rock and saw slater beetles scurrying away. I asked:

Has anyone thought of something I haven’t mentioned?

Marcus, a student in the class, asked:

How many toes does a slater have?

Why do you ask that?

Marcus replied:

They are only this long and they’re going very fast. My mini aths coach said that if I wanted to go faster I had to press back with my big toes. They must have pretty big toes to go so quick.

He continued with possibilities about how they might breathe and use energy. Marcus’ teacher reported that he often asked “quirky”, unexpected questions and had a much broader general knowledge than his peers. She had not considered the possibility he might be gifted.

Mike was solving year 12 calculus problems when he was six. He has never attended regular school but was home-schooled by his parents, who were not interested in maths. He learned about quadratic and cubic polynomials from the Khan Academy . I asked him if it was possible to draw polynomials of x to the power of 7 or 8. He did this without hesitation, noting he had never been taught to do this.

Gifted students learn in a more advanced way

People learn by converting information to knowledge. They may then elaborate, restructure or reorganise it in various ways. Giftedness is the capacity to learn in more advanced ways.

First, these students learn faster . In a given period they learn more than their regular learning peers. They form a more elaborate and differentiated knowledge of a topic. This helps them interpret more information at a time.

Second, these students are more likely to draw conclusions from evidence and reasoning rather than from explicit statements. They stimulate parts of their knowledge that were not mentioned in the information presented to them and add these inferences to their understanding.

Read more: Should gifted students go to a separate school?

This is called “ fluid analogising ” or “far transfer”. It involves combining knowledge from the two sources into an interpretation that has the characteristics of an intuitive theory about the information. This is supported by a range of affective and social factors , including high self-efficacy and intrinsic goal setting, motivation and will-power.

Their theories extend the teaching. They’re intuitive in that they’re personal and include possibilities or options the student has not yet tested. Parts of the theory may be incorrect. When given the opportunity to reflect on or field-test them, the student can validate their new knowledge, modify it or reject it.

Marcus and Mike from the earlier anecdotes engaged in these processes. So did Einstein, Churchill, Van Gogh and Christie.

Verbally gifted

A gifted learning profile manifests in multiple ways. Much of the information we’re exposed to is made up of concepts that are linked and sequenced around a topic or theme. It’s formed using agreed conventions. It may be a written narrative, a painting, a conversation or football match. Some students exposed to part of a text infer its topic and subsequent ideas – their intuitive theory about it.

These are the verbally gifted students. In the classroom they infer the direction of the teaching and give the impression of being ahead of it. This is what Mike did when he extended his knowledge beyond what the information taught him. Most of the tasks used in the Child Genius program assessed this. The children used what they knew about spelling patterns to spell unfamiliar words and to unscramble complex anagrams.

Visual-spatially gifted

Other students think about the teaching information in time and space. They use imagery and infer intuitive theories that are more lateral or creative. In the classroom their interpretations are often unexpected and may question the teaching. These are the non-verbally gifted or visual-spatially gifted students.

They frequently do not learn academic or social conventions well and are often twice exceptional. They’re more likely to challenge conventional thinking. Marcus did this when he visualised the slaters with large “beetle toes”.

What we can learn from gifted students

Educators and policy makers can learn from the student voice in the recent media programs. Some of the students on Insight told us their classrooms don’t provide the most appropriate opportunities for them to show what they know or to learn.

The twice exceptional students in the Insight program noted teachers had a limited capacity to recognise and identify the multiple ways students can be gifted. They reminded us some gifted profiles, but not the twice-exceptional profile, are prioritised in regular education.

These students thrive and excel when they have the opportunity to show their advanced interpretations initially in formats they can manage, for example, in visual and physical ways. They can then learn to use more conventional ways such as writing.

Multi-modal forms of communication are important for them. Examples include drawing pictures of their interpretations, acting out their understanding and building models to represent their understanding. The use of diagrams by the the famous physicist Richard Feynman is an example of this.

For students like Mike, adequate formal educational provision simply does not exist. With the development of information communication technology, it would be hoped that in the future adaptive and creative curricula and teaching practices could be developed for those students whose learning trajectories are far from the regular.

As a consequence, we have high levels of disengagement from regular education by some gifted students in the middle to senior secondary years. High ability Australian students under-achieve in both NAPLAN and international testing.

The problem with IQ

Identification using IQ is problematic for some gifted profiles. Some IQ tests assess a narrow band of culturally valued knowledge. They frequently do not assess general learning capacity.

As well, teachers are usually not qualified to interpret IQ assessments. The parents in the Insight program mentioned both the difficulty in having their children identified as gifted and the high costs IQ tests incurred. In Australia, these assessments can cost up to A$475 .

An obvious alternative is to equip teachers and schools to identify and assess students’ learning in the classroom for indications of gifted learning and thinking in its multiple forms. To do this, assessment tasks need to assess the quality, maturity and sophistication of the students’ thinking and learning strategies, their capacity to enhance knowledge, and also what students actually know or believe is possible about a topic or an issue.

Read more: Show us your smarts: a very brief history of intelligence testing

Classroom assessments usually don’t assess this. They are designed to test how well students have learned the teaching, not what additional knowledge the students have added to it.

Gifted students benefit from open-ended tasks that permit them to show what they know about a topic or issue. Such tasks include complex problem solving activities or challenges and open-ended assignments. We are now developing tools to assess the quality and sophistication of gifted students’ knowledge and understanding.

Tips for teachers and parents

Over the course of 2019, teachers can look for evidence of gifted learning by encouraging their students to share their intuitive theories about a topic and by completing open-ended tasks in which they extend or apply what they have learned. This can include more complex problem solving.

During reading comprehension, for example, teachers can plan tasks that require higher-level thinking, including analysis, evaluation and synthesis. Teachers need to assess and evaluate students’ learning in terms of the extent to which they elaborate on the teaching information.

Parents are often the first to notice their child learns more rapidly, remembers more, does things in more advanced ways or learns differently from their peers. Most educators have heard a parent say: “I think my child is gifted.” And sometimes the parent is correct.

Parents can use modern technology to record specific instances of high performance by their children, and share these with their child’s teachers. The mobile phone and iPad provide a good opportunity for video-recording a child’s questions during story time, their interpretations of unfamiliar contexts such as a visit to a museum, drawings or inventions the child produces and how they do this, and ways in which they solve problems in their everyday lives. These records can provide useful evidence later for educators and other professionals.

Read more: Explainer: what is differentiation and why is it poorly understood?

Parents also have a key role to play in helping their child understand what it means to learn differently from one’s peers, to value their interpretations and achievements and how they can interact socially with peers who may operate differently.

It is students’ intuitive theories about information that lead to creative, talented outcomes and innovative products. If an education system is to foster creativity and innovation, teachers need to recognise and value these theories and help these students convert them into a talent. Teachers can respond to gifted knowing and learning in its multiple forms if they know what it looks like in the classroom and have appropriate tools to identify it.

- Gifted children

- Gifted students

- gifted learning

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Head of Research Computing & Data Solutions

Community member RANZCO Education Committee (Volunteer)

Director of STEM

Chief Executive Officer

4 Ways Schools Help or Hinder Gifted Students

- Share article

The justification for gifted education is simple: Academically advanced children should be given work at their speed and level, both to nurture their talents and prevent them from becoming bored and disruptive in class.

Everything else—from how to define and identify gifted students, particularly those from traditionally underrrepresented groups, to how to serve them and nurture their long-term success—gets complicated.

“Where special ed. has a federal mandate—you must meet these students’ needs—we don’t have that,” said Jill Adelson, a research scientist at Duke University’s Talent Identification Program and the editor of the journal Gifted Child Quarterly. “We don’t even have a common definition across states of what gifted education is.”

Across several symposia at the American Educational Research Association’s annual meeting here, researchers added new wrinkles to the debate over how to academically support gifted students.

Slow Growth

For example: Prior studies have found most students experience a “summer slump,” growing faster during school years and flattening out over summers. But a study previewed at the meeting found top-performing students show less flattening from school to summer in the elementary grades—and much slower growth during the school year than average-performing students.

Karen Rambo-Hernandez of West Virginia University and Matthew Makel of Duke looked at math and reading performance in 10 states that use the NWEA MAP computer-adaptive test in reading and mathematics. The researchers compared students who tested at the mean in 3rd grade to those who tested about three grade levels ahead of that, and then followed both groups’ growth through 5th grade.

“The farther you started from your school’s mean, the slower your growth,” Rambo-Hernandez said. “In reading, the students who started at two standard deviations above the mean had much slower growth during the school year, and then they just kept trucking along with that same flow over the summer. So there was a real question as to whether or not those students were benefiting at all from their time in school.”

Top-performing students in math were more likely to show higher growth during the school year than in the summer, but in both subjects top students grew significantly slower during the school year and faster during the summer than the average student. Those who started out ahead didn’t outpace the average students’ growth during the school year until 4th grade in math and 5th grade in reading. “In theory, if you slow the kids down long enough, eventually the curriculum will catch up with them. It’s kind of sad,” Rambo-Hernandez said.

The growth study looked at top performers, whether or not they had been in gifted programs. And as other studies at the meeting suggest, both identification and services can be spotty for academically gifted students.

Better Identification?

Academically gifted students aren’t just further ahead than their classmates; research suggests they learn new concepts faster and differently. Yet districts rely on academic performance to identify gifted students, which can lead them to overlook students with disabilities and those from disadvantaged groups with less opportunity to learn.

Scott Peters, an associate education professor at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, and colleagues including Rambo-Hernandez, looked at the slowly growing trend to use district- or school-building-level comparison groups rather than national norms to identify academically advanced students while taking into account their local access to resources and challenging coursework. The reasoning goes that comparing students nationwide favors students from wealthier families and school districts that likely had more educational supports before and in the early years of school.

Using local comparison groups “is a way to maintain diversity without having to rely on something that’s really race or ethnicity-specific for legal reasons, and it works fairly well,” Peters said.

They analyzed test data for more than 3.3 million 3rd graders in 10,000 schools across 10 states: California, Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, South Carolina, Washington, and Wisconsin from 2007 to 2016. They compared the percentage of students from different racial and socioeconomic groups who would have been identified as gifted in each school had their district identified students at the top 5 percent or 15 percent of national-, district-, or school-level test performance.

Using more local-level test data did help compensate for school-level differences in students’ opportunity to learn, they found. Using the top 5 percent of students in reading at each school boosted the number of Latino students identified in reading and math by more than 150 percent. Black students were identified at more than triple the rate in reading and four times the rate in math, Peters said. Meanwhile, gifted identification rates for white and Asian students declined, though still stayed disproportionately high compared to their share of the student body.

But there’s a catch: Using school-based comparison groups only works in districts with “extreme racial segregation” in schools, Peters said. “The schools that are perfectly integrated try to use within-building norms and have no effect whatsoever,” he said.

Within-school gaps in preschool preparation and course tracking often mean that gifted programs within the same school often end up concentrating higher-income, white, and Asian-American students also.

Advanced Curriculum Lacking

Even after students are identified for gifted education, their enrichment often doesn’t align to their needs.

University of Connecticut researchers looked at three states, all of which are considered ahead of the curve for requiring that academically gifted students be both identified and served, and for tracking the district programs and student achievement of gifted students over time. They collected state and district administrative data, surveyed 2,250 schools, and visited 40 individual programs.

More than 90 percent of the districts that they studied separately identified students for being advanced in reading and language arts, and more than 85 percent identified advanced students in math, according to Rashea Hamilton, a postdoctoral researcher at UConn’s National Center for Research on Gifted Education. Yet little more than one in 10 districts used a reading curriculum designed for gifted students, and significantly fewer did so in math.

“That’s something that tends to get lost,” said D. Betsy McCoach, an education measurement and evaluation professor at the University of Connecticut and study co-author. “A kid who learns more quickly can get through the curriculum at a much faster pace.”

Researchers found in math, 62 percent to 69 percent of districts reported their curriculum focused on content above students’ grade level, and 54 percent to 69 percent of districts did so in reading. But only about half of districts said their gifted curricula moved at a faster pace in math, and significantly fewer did so in reading.

“It’s definitely easier to accelerate in math,” McCoach said. “You can be an awesome reader in 1st grade, but you’re not going to give a 1st grader [George Orwell’s novel] Animal Farm even if they could read it. There’s an asynchrony between what you have the maturity to handle, literature-wise, and what you can read and comprehend.”

Regardless of whether students were identified as gifted in reading or math, their enrichment tended to focus on “process skills” such as critical thinking, problem-solving, or creativity. In most districts, the choice of what to teach fell mostly or completely to individual teachers and varied widely from school to school.

Those findings may help explain a 2012 national study by Adelson and McCoach that found attending gifted education in kindergarten through grade 5 had no benefit for students in overall math or reading achievement.

Taking the Long View

One study did provide reason for optimism, though. Vanderbilt University’s Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth has been tracking 700 highly gifted students—the top 1 percent or higher in math achievement—for 45 years and counting.

In its latest report, researchers found that patterns of these students’ academic abilities and their social, aesthetic, and other interests at age 13 were better predictors than ability alone of what fields they entered and whether they achieved “eminence,” such as becoming CEO of a Fortune 500 company, a tenured law or research professor, or a military leader, by age 50.

“Individual ability is important [for eminence in a field], but the ability pattern matters,” said David Lubinski, a co-director of the study. “On the values inventory, if you scored high on theoretical interests and high on math ability, and relatively low on social and religious values, you’re more likely to become a physicist or engineer. If you scored high on aesthetic and verbal ability, you’re more likely to become a humanist. People who are CEOs of big organizations, scored high on reasoning and economic values, and less on theoreticals.”

The takeaway for educators, he said, is the importance of tailoring education to students’ interests as well as their abilities, and not forcing them to focus on, say, entering a science field because they are skilled in science or math.

“These precocious kids are brought to the attention of teachers because they are so conspicuously talented, like a 7-foot-8-inch high school freshman will stick out to the basketball coach,” Lubinski said. “But there are a lot of tall kids who don’t care to play basketball, thank you very much, and there are math-precocious kids who aren’t interested in being a physicist, but in fighting terrorism or managing other organizations.

“People sometimes think that’s a waste,” he said, “but when we look where they are going, these kids are not not developing their talents; they are developing their talents in other areas. It’s important to let kids keep their options open.”

A version of this article appeared in the April 17, 2019 edition of Education Week as Studies Show How Schools Hinder or Help Gifted Students

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Who Are The 'Gifted And Talented' And What Do They Need?

Anya Kamenetz

Ron Turiello's daughter, Grace, seemed unusually alert even as a newborn.

At 7 months or so, she showed an interest in categorizing objects: She'd take a drawing of an elephant in a picture book, say, and match it to a stuffed elephant and a realistic plastic elephant.

At 5 or 6 years old, when snorkeling with her family in Hawaii, she identified a passing fish correctly as a Heller's barracuda, then added, "Where are the rest? They usually travel in schools."

With a child so bright, some parents might assume that she'd do great in any school setting, and pretty much leave it at that. But Turiello was convinced she needed a special environment, in part because of his own experience. He scored very high on IQ tests as a child, but almost dropped out of high school. He says he was bored, unmotivated, socially isolated.

How The U.S. Is Neglecting Its Smartest Kids

"I took a swing at the teacher in second grade because she was making fun of my vocabulary," he recalls. "I would get bad grades because I never did my homework. I could have ended up a really well-read homeless person."

Turiello, now an attorney, and his wife, Margaret Caruso, have two children who attend a private school in Sunnyvale, Calif., exclusively for the gifted. It's called Helios, and it uses project-based learning, groups children by ability not age, and creates an individualized learning plan for each student. For Turiello, the biggest benefits to Grace, now 11, and son Marcello, 7, are social and emotional. "They don't have to pretend to be something they're not," says Turiello. "If they can be among peers and be themselves, that can really change their lives."

Estimates vary, but many say there are around 3 million students in K-12 classrooms nationwide who could be considered academically gifted and talented. The education they get is the subject of a national debate about what our public schools owe to each child in the post-No Child Left Behind era.

When it comes to gifted children, there are three big questions: How to define them, how to identify them and how best to serve them.

Skip A Grade? Start Kindergarten Early? It's Not So Easy

1. How do you define giftedness?

One of the most popular definitions, dating to the early 1990s, is "asynchronous development." That means, roughly, a student whose mental capacities develop ahead of chronological age. This concept matches the most popular tests of giftedness: IQ tests. Scores are indexed to age, with 100 as the average; a 6 year old who gives answers characteristic of a 12 year old would have an IQ of 200.

But there are problems with this framework. No 6-year-old is truly mentally identical to a 12-year-old. He or she may be brilliant at mathematics but lack background knowledge or impulse control.

In addition, IQ tests become less useful as children get older because there is less "headroom" on the test, especially for those who are already high scorers. "It's like measuring a 6-foot person with a 5-foot ruler," says Linda Silverman, an educational psychologist and founder of the Institute for the Study of Advanced Development.

Recent intelligence research de-emphasizes IQ alone and focuses on social and emotional factors.

"There's research that these other things like motivation and grit can take you to the same exact academic outcomes as someone with a higher IQ but without those things," says Scott Barry Kaufman, a psychologist who studies intelligence and creativity at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of the book Ungifted . "That's a really important finding that is just totally ignored. Our country has a narrow view of what counts as merit."

Of course, as the definitions get broader, the measurements get more subjective and thus, perhaps, less useful. Some centers for gifted children put out checklists of "giftedness" so broad that any proud parent would be hard-pressed not to recognize her child. Things like: "Has a vivid imagination." "Good sense of humor." "Highly sensitive."

1(a). How many students should be designated gifted?

It can be useful for education policy purposes to think about giftedness as it relates to the rest of the special education spectrum. Silverman argues that just as children with IQ scores two full standard deviations below the norm need special classrooms and extra resources, those who score two standard deviations above the norm need the same. By her lights, the population we should be focusing on is the top 2.5 percent to 3 percent of achievers, not the top 5 to 10 percent.

Scott Peters disagrees. He's a professor of education at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater who prepares teachers for gifted certifications. He says the question that every teacher and every school should be asking is, "How will we serve the students who already know what I'm covering today?"

In a school where most children are in remediation, he argues, a child who is simply performing on grade level may need special attention.

2. How do you identify gifted students?

The most common answer nationwide is: First, by teacher and/or parent nomination. After that come tests.

Minority and free-reduced lunch students are extremely underrepresented in gifted programs nationwide. The problem starts with that first step. Less-educated or non-English-speaking parents may not be aware of gifted program opportunities. Pre-service teachers, says Peters, typically get one day of training on gifted students, which may not prepare them to recognize giftedness in its many forms.

Research shows that screening every child , rather than relying on nominations, produces far more equitable outcomes.

Tests have their problems, too, says Kaufman. IQ and other standardized tests produce results that can be skewed by background cultural knowledge, language learner status and racial and social privilege. Even nonverbal tasks like puzzles are influenced by class and cultural background.

Using a single test-score cutoff as the criteria is common but not considered best practice.

In addition, the majority of districts in the U.S. test children for these programs before the third grade. Experts worry that identifying children only at the outset of school can be a problem, because abilities change over time, and the practice favors students who have an enriched environment at home.

Experts prefer the use of multiple criteria and multiple opportunities. Portfolios or auditions, interviews or narrative profiles may be part of the process.

3. How do you best serve gifted students?

This is the biggest controversy in gifted education. Peters says many districts focus their resources on identifying gifted or advanced learners, while offering little or nothing to serve them.

"There are cases where parents spend years advocating for students, kids get multiple rounds of testing, and at the end of the day they're provided with a little bit of differentiation or an hour of resource-room time in the course of a week," he says. "That's not sufficient for a fourth-grader, say, who needs to take geometry."

While this emphasis on diagnosis over treatment might seem paradoxical, it's compliant with the law:

In most states the law governs the identification of gifted students. But only 27 percent of districts surveyed in 2013 report a state law about how to group these students, whether in a self-contained program, or pulled out into a resource room for a single subject or offered differentiation within a classroom. And almost no states have laws mandating anything about the curriculum for gifted students.

In addition to a need to move faster and delve deeper, students whose intellectual abilities or interests don't match those of their peers often have special social and emotional needs.

"I believe that every single day in school a gifted child has the right to learn something new — not to help the teacher," Silverman says. "And to be protected from bullying, teasing and abuse."

Helping gifted students may or may not take many more resources. But it does require a shift in mindset to the idea that "every child deserves to be challenged," as Ron Turiello says.

That's why, paradoxically, many of the gifted education experts I interviewed didn't like the label "gifted." "In a perfect world, every student would have an IEP," says Kaufman.

As it happens, federal education policy is currently being reconfigured around some version of that idea.

"The whole NCLB era, and really back to the first Elementary and Secondary Education Act in the 1960s, was about getting kids to grade level, to minimal proficiency," says Peters. "There seems to be a change in belief now — that you need to show growth in every student."

That means, instead of just focusing on the 50 percent of kids who are below average, teachers should be responsible for the half who are above average, too. "That's huge. It's hard to articulate how big of a sea change that is."

Correction Oct. 2, 2015

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Ron Turiello helped found Helios School. Turiello is a former board member at the school.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Neag School of Education

Renzulli Center for Creativity, Gifted Education, and Talent Development

Reflections on the education of gifted and talented students in the twentieth century: milestones in the development of talent and gifts in young people, sally m. reis university of connecticut professor, educational psychology, university of connecticut president of the national association for gifted children.

In the recently released federal report on the status of education for our nation’s most talented students entitled National Excellence, A Case for Developing America’s Talent (O’Connell-Ross, l993), a quiet crisis is described in the education of talented students in the United States. The report clearly indicates the absence of attention paid to this population: “Despite sporadic attention over the years to the needs of bright students, most of them continue to spend time in school working well below their capabilities. The belief espoused in school reform that children from all economic and cultural backgrounds must reach their full potential has not been extended to America’s most talented students. They are underchallenged and therefore underachieve” (p. 5). The report further indicates that our nation’s talented students are offered a less rigorous curriculum, read fewer demanding books, and are less prepared for work or postsecondary education than top students in many other industrialized countries. Given this depressing appraisal, it seems a timely endeavor to reflect upon the most important accomplishments in the field of gifted education in the twentieth century. The following accomplishments emerge as major accomplishments on my list.

For many years, psychometricians and psychologists, following in the footsteps of Lewis Terman in 1916, equated giftedness with high IQ. This “legacy” survives to the present day, in that giftedness and high IQ continue to be equated in some conceptions of giftedness. Since that early time, however, other researchers (e.g., Cattell, Guilford, and Thurstone) have argued that intellect cannot be expressed in such a unitary manner, and have suggested more multifaceted approaches to intelligence (Wallace & Pierce, 1992). Research conducted in the 1980s and 1990s has provided data which support notions of multiple components to intelligence. This is particularly evident in the reexamination of “giftedness” by Sternberg and Davidson (1986) in their edited Conceptions of Giftedness . The 16 different conceptions of giftedness presented (those of Albert and Runco; Bamberger; Borkowski and Peck; Csikszentmihalyi and Robinson; Davidson; Feldhusen; Feldman and Benjamin; Gallagher and Courtwright; Gruber; Haensly, Reynolds, and Nash; Jackson and Butterfield; Renzulli; Stanley and Benbow; Sternberg; Tannenbaum; and Walters and Gardner), although distinct, are interrelated in several ways. Most of the investigators define giftedness in terms of multiple qualities, not all of which are intellectual. IQ scores are often viewed as inadequate measures of giftedness. Motivation, high self-concept, and creativity are key qualities in many of these broadened conceptions of giftedness (Siegler & Kotovsky, 1986).

Howard Gardner’s (1983) theory of multiple intelligences (MI) and Joseph Renzulli’s (1978) “three ring” definition of gifted behavior serve as precise examples of multifaceted and expanded conceptualizations of intelligence and giftedness. Gardner’s definition of an intelligence is “the ability to solve problems, or create products, that are valued within one or more cultural settings” (Gardner, 1993, p. x). Within his MI theory, he articulates at least seven specific intelligences: linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. Gardner believes that people are much more comfortable using the term “talents” and that “intelligence” is generally reserved to describe linguistic or logical “smartness”; however, he does not believe that certain human abilities should arbitrarily qualify as “intelligence” over others (e.g., language as an intelligence vs. dance as a talent) (Gardner, 1993).

Renzulli’s (1978) definition, which defines gifted behaviors rather than gifted individuals, is composed of three components as follows:

Characteristics which may be manifested in Renzulli’s three clusters are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Taxonomy of Behavioral Manifestations of Giftedness According to Renzulli’s “Three-ring” Definition of Gifted Behaviors

- high levels of abstract thought

- adaptation to novel situations

- rapid and accurate retrieval of information

Above Average Ability (specific)

- applications of general abilities to specific area of knowledge

- capacity to sort out relevant from irrelevant information

- capacity to acquire and use advanced knowledge and strategies while pursuing a problem

Task Commitment

- capacity for high levels of interest, enthusiasm

- hard work and determination in a particular area

- self-confidence and drive to achieve

- ability to identify significant problems within an area of study

- setting high standards for one’s work

- fluency, flexibility and originality of thought

- open to new experiences and ideas

- willing to take risks

- sensitive to aesthetic characteristics

(adapted from Renzulli & Reis, 1997, p. 9)

The United States federal government also subscribed to a multifaceted approach to giftedness as early as 1972 when the Marland Report definition was passed (Public Law 91-230, section 806). The Marland , or “U.S. Department of Education,” definition has dominated most states’ definitions of giftedness and talent (Passow & Rudnitski, 1993). The most recent federal definition was cited in the Jacob K. Javitz Gifted and Talented Students Education Act of 1988, and is discussed in the most recent national report on the state of gifted and talented education:

Though many school districts adopt this or other broad definitions as their philosophy, others still only pay attention to “intellectual” ability when both identifying and serving students. And, even though we have more diverse definitions of giftedness and intelligence today, many students with gifts and talents go unrecognized and underserved (Hishinuma & Tadaki, 1996; Kloosterman, 1997) perhaps due to the differing characteristics found in intellectually gifted, creatively gifted, and diverse gifted learners.Common themes identified by the implicit theorists include the need to identify the domain that serves as the basis of one’s definition, whether individual or societal; the essential role that cognitive abilities and motivation play in giftedness; the importance of the developmental course of one’s talents for whether or how they are expressed; and the inevitability of how one’s abilities come together or coalesce as affected by societal forces (Sternberg & Davidson, 1986, pp. 6–7).

Sternberg’s explicit theoretic approach emphasizes three aspects of intellectual giftedness: the superiority of mental processes, including metacomponents relating intelligence to the internal world of the individual; superiority in dealing with relative novelty and in automating information processing, an experiential aspect relating cognition to one’s level of experience in applying cognitive processes in particular tasks or situations; and superiority in applying the processes of intellectual functioning, as mediated by experience, to functioning in real-world contexts, a contextual aspect. Sternberg believes that “the outward manifestation of giftedness is in superior adaptation to, shaping of and selection of environments” (1986, p. 9) and would agree with Renzulli and Tannenbaum that it can be attained in a number of ways, differing from one person to another. Recurrent themes among the explicit theorists include questioning the cognitive bases of giftedness-asking “what is it that a person can do well to be identified by this term” (Sternberg & Davidson, 1986, p. 10)-and emphasizing the importance of theory-driven empirical research as the primary means for advancing our understanding of giftedness (pp. 10–11).

Feldman (1986), like Csikszentmihalyi and Robinson, views development as a movement through a sequence of stages. Feldman, however, believes that the development of giftedness is domain specific, observing that the movement through the levels of a domain not mastered by all individuals includes three forms: the rate at which one moves to the level of mastery, the number of levels one achieves, and the domain one selects. According to Feldman, giftedness “is the outcome of a sustained coordination among sets of intersecting forces, including historical and cultural as well as social and individual qualities and characteristics” (p. 303). Walters and Gardner (1986) add the concept of crystallizing experiences that is derived from Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. According to Gardner (1983), all normal individuals are capable of seven forms of intellectual accomplishment: linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. These multiple intelligences manifest themselves early in life as abilities to process information in certain ways. During crystallized experiences, latent skills of underutilized intelligence may be activated, and an individual’s major life activities may change as a result of such an experience.

Bloom and his associates at the University of Chicago also engaged in a study of the development of talent in children, examining the processes by which young people who reached the highest levels of accomplishment developed their capabilities. Groups studied included concert pianists, sculptors, research mathematicians, research neurologists, Olympic swimmers, and tennis champions who attained these high levels of accomplishment before the age of 35. According to Bloom and his associates, the following factors play a role in the development of talent: the home environment, which develops the work ethic and the importance of doing one’s best at all times; the encouragement of parents in a highly approved talent field; the involvement of families and teachers; and the presence of achievement and progress, which are necessary to maintain a commitment to talent over a decade of increasingly difficult learning (Bloom, 1985, pp. 508–509).

The importance of development throughout the lifespan of the individual is reinforced by each of these developmental theorists, as is the domain-specific nature of giftedness. Gifted individuals are seen as those who can excel usually in one domain, providing that the environmental factors allow this excellence to manifest itself. These developmental psychologists also emphasize the insights gained from intensive case study research and qualitative or naturalistic methodology.

The accomplishments of the last 40 years in the education of gifted students since the launching of Sputnik in the United States should not be underestimated; the field of education of the gifted, although still historically in its infancy, has emerged as strong, visible, and viable. The most recent comprehensive United States Gifted and Talented Education Report (Council of State Directors, 1994) shows that 47 states, plus Puerto Rico and Guam, have recognized education of the gifted and talented through specific legislation, and the same number of states have assigned state department of education staff to leadership positions in this area. Twenty-nine states have either a policy or position statement from the state board of education supporting the education of the gifted and talented. The report also shows that since 1963, when Pennsylvania first required services for the gifted and talented, 24 other states and Guam have implemented a mandate for services. Twenty-two other states that do not have a mandate support permissive (discretionary) programs for the gifted and talented. This growth has not been constant, however, researchers and scholars in the field have pointed to various high and low points of national interest and commitment to educating the gifted and talented (Gallagher, 1979; Renzulli, 1980; Tannenbaum, 1983). Gallagher described the struggle between support and apathy for special programs for this population as having roots in historical tradition-the battle against an aristocratic elite and our concomitant belief in egalitarianism. Tannenbaum portrays two peak periods of interest in the gifted as the five years following Sputnik in 1957 and the last half of the decade of the 1970s. Tannenbaum described a valley of neglect between the peaks in which the public focused its attention on the disadvantaged and the handicapped. “The cyclical nature of interest in the gifted is probably unique in American education. No other special group of children has been alternately embraced and repelled with so much vigor by educators and laypersons alike” (Tannenbaum, 1983, p.16). Renzulli (1980) raised similar concerns when comparing the gifted child movement with the progressive education movement of the 1930s and 1940s, stating that the field has been alternately embraced and rejected by general educators, parents, and laypeople, and he offers suggestions for dealing with some of the criticisms leveled at proponents of a differentiated education for gifted and talented students. “Simply stated, the field of education for the gifted and talented must develop as strong and defensible a rationale for the practices it advocates as has been developed for those things that it is against” (p. 3).

Excellent educational research continues to be conducted by scholars in the field and at research-based university programs. In the mid-seventies, only one programming model had been developed for gifted programs; by 1986, a textbook on systems and models for gifted programs included 15 models for elementary and secondary programs (Renzulli, 1986b). The Jacob Javits Legislation passed in 1990 by the federal government resulted in the creation of a National Research Center for the Gifted and Talented which involves three universities (The University of Connecticut and Yale University, state departments of education in every state and a consortium of over 300 school districts from across the country.

Too often, the majority of young people participating in gifted and talented programs across the country continue to represent the majority culture in our society. Few doubts exist regarding the reasons that economically disadvantaged and other minority group students are underrepresented in gifted programs. For example, Frasier and Passow (1994) indicate that identification and selection procedures may be ineffective and inappropriate for the identification of these young people. They also indicate that limited referrals and nominations of students who are minorities or from other disadvantaged groups affect their eventual placement in programs. Test bias and inappropriateness have been mentioned as a reason as the continued reliance on traditional identification approaches. Groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in gifted programs could be better served, according to Frasier and Passow (1994), if the following elements are considered: new constructs of giftedness, attention to cultural and contextual variability, the use of more varied and authentic assessment, performance identification, identification through learning opportunities, and attention to both absolute attributes of giftedness, the traits, aptitudes, and behaviors universally associated with talent as well as the specific behaviors that represent different manifestations of gifted potential and performance as a consequence of the social and cultural contexts in which they occur (p. xvii).

In addition to students from economically disadvantaged populations, various minority and cultural groups, as well as gifted students with various disabilities such as learning disabilities, visual and hearing impairments, and physical handicaps. Another group of students who are traditionally underrepresented in gifted programs are females who have potential in mathematics and science, as well as gifted females who achieve in school but later underachieve in life (Reis, 1987). Special programs, strategies, and identification procedures have been suggested for many of these groups, however, much progress still remains to be made to achieve equity for these underrepresented groups.

In the last decade many promising practices have been implemented in the education of gifted and talented students. More primary and secondary programs have been developed since the first programming model, The Enrichment Triad Model (Renzulli, 1977) was developed for gifted students. Other programming models such as The Purdue Three-Stage Enrichment Model (Feldhusen & Kolloff, l986); Talents Unlimited (Schlichter, 1986); The Autonomous Learner Model (Betts, l986) are also widely used throughout the country. National programs such as Future Problem Solving, which was conceived by Dr. E. Paul Torrance, have taught hundreds of thousands of students to apply problem-solving techniques to the real problems of our society. Although not developed solely for gifted students, Future Problem Solving is widely used in gifted programs because of the curricular freedom associated with these programs.

The Future Problem Solving Program is a year-long program in which teams of four students use a six-step problem solving process to solve complex scientific and social problems of the future such as the overcrowding of prisons or the greenhouse effect. At regular intervals throughout the year, the teams mail their work to evaluators, who review it and return it with their suggestions for improvement. As the year progresses, the teams become increasingly more proficient at problem solving. The Future Problem Solving Program takes students beyond memorization. The program challenges students to apply information they have learned to some of the most complex issues facing society. They are asked to think, to make decisions, and, in some instances, to carry out their solutions.

A national program called Talent Search actively recruits and provides testing and program opportunities for mathematically precocious youth. Talent Search is an annual effort to identify 12-14 year old students who score in the top five percent of the country in mathematics on the SAT math test. These students generally have scored highly in other standardized tests and are recommended by teachers or counselors to take the SAT-Math. If they do well on this test, they are eligible for multiple options including summer programs, grade skipping, completing two or more years of a math subject in one year, taking college courses, or other options. Eleven states have created separate schools for talented students in math and science such as The North Carolina School for Math and Science. Some large school districts have established magnet schools to serve the needs of talented students. In New York City, for example, the Bronx High School of Science has helped to nurture and develop mathematical and scientific talent for decades, producing internally known scientists and Nobel laureates. In other states, Governor’s Schools provide advanced, intensive summer programs in a variety of content areas. It is clear, however, that these opportunities touch a small percentage of students who could benefit from them.

Within the schools that have gifted programs, limited options often exist. Resource room programs in which a student leaves his/her regular classroom and spends a limited amount of time doing independent study or becoming involved in advanced research in a resource room for gifted students with a teacher are commonly found. Independent study projects provide talented students with opportunities to engage in pursuing individual interests and advanced content. Many local districts have created innovative mentorship programs which pair a bright student with a high school student or adult who has an interest in the same area as the student. Some schools use cluster grouping which allows students who are gifted in a certain content area to be grouped in one classroom with other students who are talented in the same area. Therefore, one fifth grade teacher may have six students who are advanced in mathematics in a classroom instead of having these six students distributed among four different fifth grade classrooms. Some schools acknowledge that they can do little different for gifted students within the school day and provide after school enrichment programs or send talented students to Saturday programs offered by museums, science centers, or local universities. Unfortunately, many of these promising strategies seem insignificant when compared with the plight of thousands of bright students who still sit in classrooms across the country bored, unmotivated, and unchallenged.

Acceleration, once a standard practice in our country, is too often dismissed by teachers and administrators as an inappropriate practice for a variety of reasons, including scheduling problems, concerns about the social effects of grade skipping, and others. Many forms of acceleration hold promise for gifted students including enabling precocious students to enter kindergarten or first grade early, grade skipping, and early entrance to college are not commonly used or encouraged by most school districts. And in many schools, the pervasive influence of anti-intellectualism that affects our society has a two pronged effect. First, policy makers do little to encourage excellence in our schools and less and less attention is paid to intellectual growth. Second, peer pressure is exerted on gifted students. The labels such as “smarty-pants” commonly used to describe bright students in the fifties and sixties has been replaced by more negative labels such as “nerd”, “dweeb” or “dork”. Our brightest students often learn not to answer in class, to stop raising their hands and to minimize their abilities to avoid peer pressures.

A number of challenging curriculum options in science and language arts have been developed under the auspices of the federal Javits Education Act mentioned earlier. Several national programs have been developed or implemented for high ability students in many districts, regional service centers, and states. Many high ability students have the opportunity to participate in History Day in which students work individually or in small groups on an historical event, person from the past, or invention related to a theme that is determined each year. Using primary source data including diaries or other sources gathered in libraries, museums, and interviews, students prepare research papers, projects, media presentations or performances as entries. These entries are judged by local historians, educators, and other professionals and state finalists compete with winners from other states each June. Information about History Day can be obtained from state historical societies. Many model projects such as mentorships, Saturday programs, summer internships, and computer camps that are of extremely high quality continue to be implemented.

Much that has been learned and developed in gifted programs can offer exciting, creative alternatives in instruction and curriculum for all students. A rather impressive menu of exciting curricular adaptations, independent study and thinking skill strategies, grouping options, and enrichment strategies have been developed in gifted programs which could be used to improve schools. The Schoolwide Enrichment Model (Renzulli & Reis, 1985: 1007) has been field tested and implemented by hundreds of school districts across the country for the last nine years. Our experiences with schoolwide enrichment led us to realize that when an effective approach to enrichment is implemented, all students in the school benefit and the entire school begins to improve. This led to the development of Schools for Talent Development (Renzulli, 1994). This approach seeks to apply strategies used in gifted programs to the entire school population, emphasizing talent development in all students through a variety of acceleration and enrichment strategies that have been discussed earlier. Not all students can, of course, participate in all advanced opportunities but many can work far beyond what they are currently asked to do. It is clear that our most advanced students need different types of educational experiences than they are currently receiving and that without these services, talents may not be nurtured in many American students, especially those who attend schools in which survival is a major daily goal.

Specialists in the area of gifted education have also gained expertise in adjusting the regular curriculum to meet the needs of advanced students in a variety of ways including: accelerating content, incorporating a thematic approach, and substituting more challenging textbooks or assignments. The present range of instructional techniques used in most classrooms observed by Goodlad (1984) and his colleagues is vastly different than what is recommended in many gifted programs today. The flexibility in grouping that is encouraged in many gifted programs might also be helpful in other types of educational settings.

We can, therefore, make every attempt to share with other educators the technology we have gained in teaching students process skills, modifying the regular curriculum, and helping students become producers of knowledge (Renzulli, 1977). We can extend enrichment activities and provide staff development in the many principles that guide our programming models. Yet, without the changes at the local, state and national policy making levels that will alter the current emphasis on raising test scores and purchasing unchallenging, flat and downright sterile textbooks, our efforts may be insignificant.

These questions have led us to advocate a fundamental change in the ways the concept of giftedness should be viewed in the future. Except for certain functional purposes related mainly to professional focal points (i.e., research, training, legislation) and to ease-of-expression, we believe that labeling students as “the gifted” is counter-productive to the educational efforts aimed at providing supplementary educational experiences for certain students in the general school population. We believe that our field should shift its emphasis from a traditional concept of “being gifted” (or not being gifted) to a concern about the development of gifted behaviors in those youngsters who have the highest potential for benefiting from special educational services. This slight shift in terminology might appear insignificant, but we believe that it has implications for the entire way that we think about the concept of giftedness and the ways in which we should structure our identification and programming endeavors. This change in terminology may also provide the flexibility in both identification and programming endeavors that will encourage the inclusion of at-risk and underachieving students in our programs. If that occurs, not only will we be giving these high potential youngsters an opportunity to participate, we will also help to eliminate the charges of elitism and bias in grouping that are sometimes legitimately directed at some gifted programs.

We cannot forget that our schools should be places that seek to develop talents in children. We won’t produce future Thomas Edisons or Marie Curies by forcing them to spend large amounts of their science and mathematics classes tutoring students who don’t understand the material. A student who is tutoring others in a cooperative learning situation in mathematics may refine some of his or her basic skill processes, but this type of situation does not provide the level of challenge necessary for the most advanced types of involvement in the subject, nor for inspiring our young people to strive to develop their talents.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Free printable to elevate your AI game 🤖

50 Tips, Tricks and Ideas for Teaching Gifted Students

Use these ideas to engage the high-level thinkers in your classroom.

Gifted kids can be a joy to teach when you know how to identify what engages them. These 50 tips and tricks come from my own experience and from around the Web. They’re good to have in your bag of tricks whether you’re a newbie or an old hand at teaching these high-level thinkers.

1. Know Their Interests

Every year, I start by having my students complete an interest inventory . This helps me ensure that curriculum is personalized to their interests.

2. Try Book Talks