Essay on Independence And Individuality

Students are often asked to write an essay on Independence And Individuality in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Independence And Individuality

Understanding independence.

Independence means making choices for yourself without others telling you what to do. Like a bird flying alone, it’s about being free to live your life. When you pick your clothes or decide on a game to play, that’s you being independent. It’s important because it helps you grow and learn to trust yourself.

What is Individuality?

The power of being you.

When you mix independence with individuality, you become strong and confident. You’re like a superhero with your own powers. By choosing your path and being true to yourself, you can achieve great things. Remember, being independent and individual is about celebrating who you are.

250 Words Essay on Independence And Individuality

What is independence.

Independence means being able to do things on your own, without needing help from others. It’s like when you learn to tie your shoes by yourself. You feel proud and capable because you don’t have to wait for someone to do it for you. Being independent is important because it helps you grow and make your own choices.

Why Independence Is Important

Being independent helps you become stronger. You learn to solve problems, like figuring out a difficult homework question on your own. It also gives you the freedom to choose what you want to do, whether it’s picking a game to play or deciding what to eat for lunch.

Why Individuality Matters

Your individuality lets you express who you are. It could be through the clothes you wear, the music you enjoy, or the way you decorate your room. When you share your own ideas and style, you make the world more interesting.

Bringing Them Together

Independence and individuality go hand in hand. When you’re independent, you can make choices that reflect your individuality. Both are keys to being happy with who you are and living a life that’s true to yourself. Remember, being different is good, and being able to stand on your own makes you strong.

500 Words Essay on Independence And Individuality

Independence means being able to make choices for yourself and do things without needing help from others. It is like when you learn to tie your shoes by yourself or make a sandwich without anyone’s help. For grown-ups, it means they can make bigger decisions, like where to work or live, without asking for permission or waiting for someone else to tell them what to do.

Understanding Individuality

Individuality is what makes you unique from everyone else. It is the special mix of qualities, likes, and dislikes that makes you, well, you! Just like no two snowflakes are the same, no two people are exactly alike. Your individuality is like your personal fingerprint on the world—it shows who you are and what you stand for.

Independence Helps Individuality Grow

The balance between getting help and being independent.

It’s important to remember that even though independence is good, asking for help is okay too. Everyone needs a little help sometimes, and it doesn’t mean you’re not independent. It’s like when you’re learning to ride a bike. At first, you might need training wheels or someone to hold on, but eventually, you learn to ride on your own. Getting help is part of the journey to doing things by yourself.

Why Individuality is Important

Your individuality is important because it is all about what makes you special. It’s like having your own superpower that nobody else has. When you are true to yourself and show your unique qualities, you add something special to the world that wasn’t there before. It’s like adding a new color to a painting that makes it even more beautiful.

How to Respect Others’ Independence and Individuality

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- The Columbian Exchange

- De Las Casas and the Conquistadors

- Early Visual Representations of the New World

- Failed European Colonies in the New World

- Successful European Colonies in the New World

- A Model of Christian Charity

- Benjamin Franklin’s Satire of Witch Hunting

- The American Revolution as Civil War

- Patrick Henry and “Give Me Liberty!”

- Lexington & Concord: Tipping Point of the Revolution

- Abigail Adams and “Remember the Ladies”

- Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” 1776

- Citizen Leadership in the Young Republic

- After Shays’ Rebellion

- James Madison Debates a Bill of Rights

- America, the Creeks, and Other Southeastern Tribes

- America and the Six Nations: Native Americans After the Revolution

- The Revolution of 1800

- Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase

- The Expansion of Democracy During the Jacksonian Era

- The Religious Roots of Abolition

Individualism in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”

- Aylmer’s Motivation in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”

- Thoreau’s Critique of Democracy in “Civil Disobedience”

- Hester’s A: The Red Badge of Wisdom

- “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

- The Cult of Domesticity

- The Family Life of the Enslaved

- A Pro-Slavery Argument, 1857

- The Underground Railroad

- The Enslaved and the Civil War

- Women, Temperance, and Domesticity

- “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint,” 1873

- “To Build a Fire”: An Environmentalist Interpretation

- Progressivism in the Factory

- Progressivism in the Home

- The “Aeroplane” as a Symbol of Modernism

- The “Phenomenon of Lindbergh”

- The Radio as New Technology: Blessing or Curse? A 1929 Debate

- The Marshall Plan Speech: Rhetoric and Diplomacy

- NSC 68: America’s Cold War Blueprint

- The Moral Vision of Atticus Finch

Advisor: Charles Capper, Professor of History, Boston University; National Humanities Center Fellow Copyright National Humanities Center, 2014

Lesson Contents

Teacher’s note.

- Text Analysis & Close Reading Questions

Follow-Up Assignment

- Student Version PDF

In his essay “Self-Reliance,” how does Ralph Waldo Emerson define individualism, and how, in his view, can it affect society?

Understanding.

In “Self-Reliance” Emerson defines individualism as a profound and unshakeable trust in one’s own intuitions. Embracing this view of individualism, he asserts, can revolutionize society, not through a sweeping mass movement, but through the transformation of one life at a time and through the creation of leaders capable of greatness.

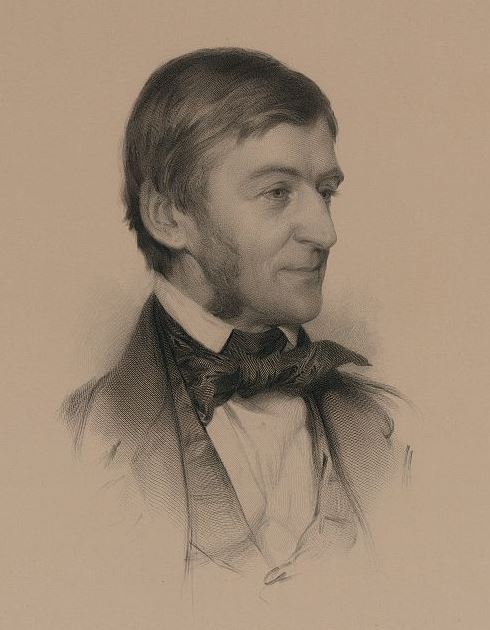

Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1878

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance” , 1841.

Essay, Literary nonfiction.

Text Complexity

Grade 11-CCR complexity band. For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org .

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-Literacy.L.11-12.4 (Determine the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases.)

- ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.1 (Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as drawing inferences.)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 4.1 – II.A. (…Romantic beliefs in human perfectibility fostered the rise of voluntary organizations to promote religious and secular reforms…)

- Key Concept 4.1 – III.A. (A new national culture emerged…that combined European forms with local and regional cultural sensibilities.)

- Skill Type III: Skill 7 (Analyze features of historical evidence such as audience, purpose, point of view…)

Advanced Placement English Language and Composition

- Reading nonfiction

- Evaluating, using, and citing primary sources

- Writing in several forms about a variety of subjects

“Self-Reliance” is central to understanding Emerson’s thought, but it can be difficult to teach because of its vocabulary and sentence structure. This lesson offers a thorough exploration of the essay. The text analysis focuses on Emerson’s definition of individualism, his analysis of society, and the way he believes his version of individualism can transform — indeed, save — American society.

The first interactive exercise, well-suited for individual or small group work, presents some of Emerson’s more famous aphorisms as tweets from Dr. Ralph, a nineteenth-century self-help guru, and asks students to interpret and paraphrase them. The second invites students to consider whether they would embrace Dr. Ralph’s vision of life. It explores paragraph 7, the most well-developed in the essay and the only one that shows Emerson interacting with other people to any substantial degree. The exercise is designed to raise questions about the implications of Emersonian self-reliance for one’s relations with others, including family, friends, and the broader society. The excerpt illustrates critic’s Louis Menand’s contention, cited in the background note, that Emerson’s essays, although generally taken as affirmations, are “deeply unconsoling.”

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, access to the interactive exercises, and a follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive worksheet that can be e-mailed, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions.

| (continues below) | (click to open) |

Teacher’s Guide

Background questions.

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

- When was it written?

- What was going on at the time of its writing that might have influenced its composition?

Ralph Waldo Emerson died in 1882, but he is still very much with us. When you hear people assert their individualism, perhaps in rejecting help from the government or anyone else, you hear the voice of Emerson. When you hear a self-help guru on TV tell people that if they change their way of thinking, they will change reality, you hear the voice of Emerson. He is America’s apostle of individualism, our champion of mind over matter, and he set forth the core of his thinking in his essay “Self-Reliance” (1841).

While they influence us today, Emerson’s ideas grew out of a specific time and place, which spawned a philosophical movement called Transcendentalism. “Self-Reliance” asserts a central belief in that philosophy: truth lies in our spontaneous, involuntary intuitions. We do not have the space here to explain Transcendentalism fully, but we can sketch some out its fundamental convictions, a bit of its historical context, and the way “Self-Reliance” relates to it.

By the 1830s many in New England, especially the young, felt that the religion they had inherited from their Puritan ancestors had become cold and impersonal. In their view it lacked emotion and failed to foster that sense of connectedness to the divine which they sought in religion. To them it seemed that the church had taken its eyes off heaven and fixed them on the material world, which under the probings, measurements, and observations of science seemed less and less to offer assurance of divine presence in the world.

Taking direction from ancient Greek philosophy and European thinking, a small group of New England intellectuals embraced the idea that men and women did not need churches to connect with divinity and that nature, far from being without spiritual meaning, was, in fact, a realm of symbols that pointed to divine truths. According to these preachers and writers, we could connect with divinity and understand those symbols — that is to say, transcend or rise above the material world — simply by accepting our own intuitions about God, nature, and experience. These insights, they argued, needed no external verification; the mere fact that they flashed across the mind proved they were true.

To hold these beliefs required enormous self-confidence, of course, and this is where Emerson and “Self-Reliance” come into the picture. He contends that there is within each of us an “aboriginal Self,” a first or ground-floor self beyond which there is no other. In “Self-Reliance” he defines it in mystical terms as the “deep force” through which we “share the life by which things exist.” It is “the fountain of action and thought,” the source of our spontaneous intuitions. This self defines not a particular, individual identity but a universal, human identity. When our insights derive from it, they are valid not only for us but for all humankind. Thus we can be assured that what is true in our private hearts is, as Emerson asserts, “true for all men.”*

But how can we tell if our intuitions come from the “aboriginal Self” and are, therefore, true? We cannot. Emerson says we must have the self-trust to believe that they do and follow them as if they do. If, indeed, they are true, eventually everyone will accept them, and they will be “rendered back to us” as “the universal sense.”

Daguerrotype of Ralph Waldo Emerson

While “Self-Reliance” deals extensively with theological matters, we cannot overlook its political significance. It appeared in 1841, just four years after President Andrew Jackson left office. In the election of 1828 Jackson forged an alliance among the woodsmen and farmers of the western frontier and the laborers of eastern cities. (See the America in Class® lesson “The Expansion of Democracy during the Jacksonian Era.” ) Emerson opposed the Jacksonians over specific policies, chiefly their defense of slavery and their support for the expulsion of Indians from their territories. But he objected to them on broader grounds as well. Many people like Emerson, who despite his noncomformist thought still held many of the political views of the old New England elite from which he sprang, feared that the rise of the Jacksonian electorate would turn American democracy into mob rule. In fact, at one point in “Self-Reliance” he proclaims “now we are a mob.” When you see the word “mob” here, do not picture a large, threatening crowd. Instead, think of what we today would call mass society, a society whose culture and politics are shaped not by the tastes and opinions of a small, narrow elite but rather by those of a broad, diverse population.

Emerson opposed mass-party politics because it was based on nothing more than numbers and majority rule, and he was hostile to mass culture because it was based on manufactured entertainments. Both, he believed, distracted people from the real questions of spiritual health and social justice. Like some critics today, he believed that mass society breeds intellectual mediocrity and conformity. He argued that it produces soft, weak men and women, more prone to whine and whimper than to embrace great challenges. Emerson took as his mission the task of lifting people out of the mass and turning them into robust, sturdy individuals who could face life with confidence. While he held out the possibility of such transcendence to all Americans, he knew that not all would respond. He assured those who did that they would achieve greatness and become “guides, redeemers, and benefactors” whose personal transformations and leadership would rescue democracy. Thus if “Self-Reliance” is a pep talk in support for nonconformists, it is also a manual on how to live for those who seek to be individuals in a mass society.

Describing “Self-Reliance” as a pep talk and a manual re-enforces the way most people have read the essay, as a work of affirmation and uplift, and there is much that is affirmative and uplifting in it. Yet a careful reading also reveals a darker side to Emerson’s self-reliance. His uncompromising embrace of nonconformity and intellectual integrity can breed a chilly arrogance, a lack of compassion, and a lonely isolation. That is why one critic has called Emerson’s work “deeply unconsoling.” 1 In this lesson we explore this side of Emerson along with his bracing optimism.

A word about our presentation. Because readers can take “Self-Reliance” as an advice manual for living and because Emerson was above all a teacher, we found it engaging to cast him not as Ralph Waldo Emerson, a nineteenth-century philosopher, but as Dr. Ralph, a twenty-first-century self-help guru. In the end we ask if you would embrace his approach to life and sign up for his tweets.

*Teacher’s Note: For a more detailed discussion of the “aboriginal Self,” see pp. 65-67 in Lawrence Buell’s Emerson .

1. Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club (New York; Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2001) p. 18. ↩

Text Analysis

Paragraph 1, close reading questions.

What is important about the verses written by the painter in sentence 1? They “were original and not conventional.”

From evidence in this paragraph, what do you think Emerson means by “original”? He defines “original” in sentence 6 when he says that we value the work of Moses, Plato, and Milton because they said not what others have thought, but what they thought.

In sentences 2 and 3 how does Emerson suggest we should read an “original” work? He suggests that we should read it with our souls. We should respond more to the sentiment of the work rather than to its explicit content.

In telling us how to read an original work, what do you think Emerson is telling us about reading his work? In sentences 2 and 3 Emerson is telling us how to read “Self-Reliance” and his work in general. We should attend more to its sentiment, its emotional impact, rather than to the thought it may contain. The reason for this advice will become apparent as we discover that Emerson’s essays are more collections of inspirational, emotionally charged sentences than logical arguments.

How does Emerson define genius? He defines it as possessing the confident belief that what is true for you is true for all people.

Considering this definition of genius, what does Emerson mean when he says that “the inmost in due time becomes the outmost”? Since the private or “inmost” truth we discover in our hearts is true for all men and women, it will eventually be “rendered back to us,” proclaimed, as an “outmost” or public truth.

Why, according to Emerson, do we value Moses, Plato, and Milton? We value them because they ignored the wisdom of the past (books and traditions) and spoke not what others thought but what they thought, the “inmost” truth they discovered in their own hearts. They are great because they transformed their “inmost” truth to “outmost” truth.

Thus far Emerson has said that we should seek truth by looking into our own hearts and that we, like such great thinkers as Moses, Plato, and Milton, should ignore what we find in books and in the learning of the past. What implications does his advice hold for education? It diminishes the importance of education and suggests that formal education may actually get in the way of our search for knowledge and truth.

Why then should we bother to study “great works of art” or even “Self-Reliance” for that matter? Because great works of art “teach us to abide by our spontaneous impressions.” And that is, of course, precisely what “Self-Reliance” is doing. Both they and this essay reassure us that our “latent convictions” are, indeed, “universal sense.” They strengthen our ability to maintain our individualism in the face of “the whole cry of voices” who oppose us “on the other side.”

Based on your reading of paragraph 1, how does Emerson define individualism? Support your answer with reference to specific sentences. Emerson defines individualism as a profound and unshakeable trust in one’s own intuitions. Just about any sentence from 4 through 11 could be cited as support.

Paragraph 34 (excerpt)

Note: Every good self-help guru offers advice on how to handle failure, and in the excerpt from paragraph 35 Dr. Ralph does that by describing his ideal of a self-reliant young man. Here we see Dr. Ralph at perhaps his most affirmative, telling his followers what self-reliance can do for them. Before he does that, however, he offers, in paragraph 34, his diagnosis of American society in 1841. The example of his “sturdy lad” in paragraph 35 suggests what self-reliance can do for society, a theme he picks up in paragraph 36.

What, according to Emerson, is wrong with the “social state” of America in 1841? Americans have become weak, shy, and fearful, an indication of its true problem: it is no longer capable of producing “great and perfect persons.”

Given the political context in which he wrote “Self-Reliance,” why might Emerson think that American society was no longer capable of producing “great and perfect persons”? In Emerson’s view, by giving power to the “mob,” Jacksonian democracy weakened American culture and gave rise to social and personal mediocrity.

Paragraph 35 (excerpt)

What does Emerson mean by “miscarry”? What context clues help us discover that meaning? Here “miscarry” means “to fail.” We can see that by noting the parallel structure of the first two sentences. Emerson parallels “miscarry” and “fails” by placing them in the same position in the first two sentences: “If our young men miscarry…” “If the young merchant fails,…”

What is the relationship between the young men who miscarry and the young merchants who fail in paragraph 35 and the “timorous, desponding whimperers” of paragraph 34? They are the same. The young failures illustrate the point Emerson makes in the previous paragraph about the weakness of America and its citizens.

According to Emerson, how does an “un-self-reliant” person respond to failure? He despairs and becomes weak. He loses “loses heart” and feels “ruined.” He falls into self-pity and complains for years.

Emerson structures this paragraph as a comparison between a “city doll” and a “sturdy lad.” With reference to paragraph 34 what does the “sturdy lad” represent? He represents the kind of person Emerson wants to create, the kind of person who will “renovate” America’s “life and social state.”

What are the connotations of “city doll”? The term suggests weakness with a hint of effeminacy.

Compare a “city doll” with a “sturdy lad.” City Doll: defeated by failure, urban, narrows his options by studying for a profession, learns from books, postpones life, lacks confidence and self-trust. Sturdy Lad: resilient, rural, at least expert in rural skills, “teams it, farms it”, realizes he has many options and takes advantage of them, learns from experience, engages life, possesses confidence, trusts himself.

What point does Emerson make with this comparison? Here Emerson is actually trying to persuade his readers to embrace his version of self-reliance. His comparison casts the “sturdy lad” in a positive light. We want to be like him, not like a “city doll.” Emerson suggests that, through the sort of men and women exemplified by the “sturdy lad,” self-reliance will rescue American life and society from weakness, despair, and defeat and restore its capacity for greatness.

What do you notice about the progression of the jobs Emerson assigns to his “sturdy lad”? They ascend in wealth, prestige, and influence from plow hand to member of Congress.

We have seen that Emerson hopes to raise above the mob people who will themselves be “great and perfect persons” and restore America’s ability to produce such people. What does the progression of jobs he assigns to the “sturdy lad” suggest about the roles these people will play in American society? As teachers, preachers, editors, congressmen, and land owners, they will be the leaders and opinion makers of American society. [1] If our young men miscarry in their first enterprises, they lose all heart. If the young merchant fails, men say he is ruined. [2] If the finest genius studies at one of our colleges, and is not installed in an office within one year afterwards in the cities or suburbs of Boston or New York, it seems to his friends and to himself that he is right in being disheartened, and in complaining the rest of his life. [3] A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township,* and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. [4] He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not ‘studying a profession,’ for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances.

*Emerson does not mean that the “sturdy lad” would buy a town. He probably means that he would buy a large piece of uninhabited land (townships in New England were six miles square). The point here is that he would become a substantial landowner.

Paragraph 36

In a well organized essay explain what society would be like if everyone embraced Emerson’s idea of self-reliance. Your analysis should focus on Emerson’s attitudes toward law, the family, and education. Be sure to use specific examples from the text to support your argument.

Vocabulary Pop-Ups

- admonition: gentle, friendly criticism

- latent: hidden

- naught: ignored

- lustre: brightness

- firmament: sky

- bards: poets

- sages: wise men and women

- alienated: made unfamiliar by being separated from us

- else: otherwise

- sinew: connective tissues

- timorous: shy

- desponding: discouraging

- renovate: change

- miscarry: fail

- modes: styles

- speculative: theoretical

- Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson engraved and published by Stephen A. Schoff, Newtonville, Massachusetts, 1878, from an original drawing by Samuel W. Rowse [ca. 1858] in the possession of Charles Eliot Norton. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-04133.

- Daguerreotype of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 4 x 5 black-and-white negative, creator unknown. Courtesy of the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

National Humanities Center | 7 T.W. Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 | Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 | Fax: (919) 990-8535 | nationalhumanitiescenter.org

Copyright 2010–2023 National Humanities Center. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Not All Forms of Independence Are Created Equal: Only Being Independent the “Right Way” Is Associated With Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction

Daniela moza.

1 Department of Psychology, West University of Timişoara, Timișoara, Romania

Smaranda Ioana Lawrie

2 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, United States

Laurențiu P. Maricuțoiu

Alin gavreliuc, heejung s. kim, associated data.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Past research has found a strong and positive association between the independent self-construal and life satisfaction, mediated through self-esteem, in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures. In Study 1, we collected data from four countries (the United States, Japan, Romania, and Hungary; N = 736) and replicated these findings in cultures which have received little attention in past research. In Study 2, we treated independence as a multifaceted construct and further examined its relationship with self-esteem and life satisfaction using samples from the United States and Romania ( N = 370). Different ways of being independent are associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction in the two cultures, suggesting that it is not independence as a global concept that predicts self-esteem and life satisfaction, but rather, feeling independent in culturally appropriate ways is a signal that one’s way of being fits in and is valued in one’s context.

Introduction

“The most incredible beauty and the most satisfying way of life come from affirming your own uniqueness.”

Jane Fonda, American actress

“What makes me happy? The fact that I carry my cross by myself.”

Ionut Caragea, Romanian author

A strong and positive association between the independent self-construal and life satisfaction, mediated by self-esteem, has been termed “a pancultural explanation for life satisfaction” ( Kwan et al., 1997 , p. 1038), because it held true in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures ( Kwan et al., 1997 ; Chang et al., 2011 ; Duan et al., 2013 ; Zhang, 2013 ; Yu et al., 2016 ). Life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-construal are individually linked to a wide array of factors, but the idea of researching this particular “pancultural explanation” originated in the findings of an extensive cross-cultural study ( Diener and Diener, 1995 ), which showed a much stronger correlation between self-esteem and life satisfaction in individualistic cultures compared to collectivistic cultures. Subsequent studies established that the independent self-construal is a crucial, individual-level, cultural ingredient that seems to foster self-esteem universally in individuals ( Singelis et al., 1999 ) with further positive implications for life satisfaction across cultures ( Kwan et al., 1997 ). The independent self-construal (or independence) represents the tendency of individuals to define themselves by their unique configuration of internal attributes and to focus on discovering and expressing their distinct potential ( Markus and Kitayama, 1991 ). Independence is more strongly encouraged in individualistic cultures, whereas in collectivistic cultures, interdependence is more strongly encouraged ( Markus and Kitayama, 1991 ); however, members of both types of cultures have both types of self-construals ( Singelis, 1994 ), but only independence is associated with a stronger sense of self-worth and greater life satisfaction in both cultural settings ( Kwan et al., 1997 ). Based on such pancultural findings, independence has been conceptualized and measured as a unidimensional construct and assumed to be experienced and expressed in the same way across all cultures ( Singelis, 1994 ; Gudykunst et al., 1996 ). Recent approaches to the study of culture find, however, that both independence and interdependence, along with the related cultural dimensions of individualism and collectivism, are more varied than previously assumed and that different cultures favor different ways of being independent or interdependent (see Kusserow, 1999 ; Vignoles et al., 2016 ; Campos and Kim, 2017 ; Kim and Lawrie, 2019 ).

These new findings raise the question of whether or not there is any cultural diversity in the association between independence, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. If different shades of independence are valued, experienced, and expressed across cultures, it is possible that being independent in ways that are prescribed and valued by one’s culture is associated with increased self-esteem and thus further promotes life satisfaction, but being independent in ways that are not valued by one’s culture is not associated with increased self-esteem. The present research is an attempt to test explicitly whether or not different ways of being independent are more or less linked to self-esteem and, indirectly, to life satisfaction in different cultures.

The Independence — Life Satisfaction Link

There are two possible theoretical perspectives that can explain the association between independence, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. The first perspective is that independence as a unidimensional construct contributes to self-esteem and life satisfaction across different cultures. This has been the dominant assumption in previous research ( Heine et al., 1999 ). Empirical evidence showed that independence entails the selection of internal (as opposed to social) information in life-satisfaction judgments ( Suh et al., 2008 ), specifically information that promotes and enhances the self ( Heine et al., 1999 ; Lee et al., 2000 ; Rosopa et al., 2016 ) and fosters the agentic pursuit ( Wojciszke and Bialobrzeska, 2014 ) of independent hedonic goals ( Oishi and Diener, 2001 ). The self-esteem of highly independent individuals will therefore reflect their perceived success at achieving their independent, agentic, self-promoting, hedonic goals, and consequently, they would be more satisfied with life.

The second theoretical perspective is in line with research findings suggesting that people ascribe higher value to options (e.g., an object or an activity) that are compatible with their goal orientation because they feel “right” due to a high regulatory fit ( Higgins et al., 2003 ; Higgins, 2005 ). Similarly, fitting in with one’s culture, or experiencing a culture-person fit, has positive implications for self-esteem and well-being (e.g., Leary and Baumeister, 2000 ; De Leersnyder et al., 2015 ; Cho et al., 2018 ). According to this view, even if the overall link between the independent self and life satisfaction is robust across cultures, there may be cultural differences in the “right” way of being independent that lead to increased self-esteem. That is, if different ways of being independent are highlighted and emphasized in different cultures, then being independent in culturally appropriate ways should have positive implications for self-esteem and, indirectly, for life satisfaction. However, being independent in ways that are less emphasized in one’s culture (culturally inappropriate ways) should have few positive implications and possibly even some negative implications for self-esteem and, indirectly, for life satisfaction ( Pedrotti and Edwards, 2009 ; Ryder et al., 2011 ; De Leersnyder et al., 2014 , but see also Ward et al., 2004 ). Although arguing for the universal importance of cultural fit for self-esteem and life satisfaction, this perspective also allows room for cultural differences in the specific content and definition of independence that can bring about a sense of cultural fit.

Independence as a Multidimensional Concept

There are different ways to experience and exercise independence, and different cultures may emphasize different ways of being independent. For example, one may feel good about oneself when one stands out and experiences oneself as unique and different; alternatively, one may feel good about oneself when one does not have to rely on anyone else and can take care of oneself.

The classification of cultures based on the individualism-collectivism cultural dimensions ( Hofstede et al., 2010 ) and the independent-interdependent self-construal ( Markus and Kitayama, 1991 ) has provided the theoretical framework for a tremendous amount of research which, in the past several decades, has revealed that psychological processes, including emotions, motivations, and cognitions, are profoundly influenced by culture. Despite the great empirical utility of dividing cultures according to these binary cultural dimensions, this approach has also reduced the complexity and diversity of cultures to an oversimplified contrast between individualistic and collectivistic, independent and interdependent, and East and West. One way that this simple dichotomy between “independence” and “interdependence” has been maintained has been through the widespread use of the Singelis’s self-construal scale (1994), which measures the two dimensions as sperate and distinct constructs. This binary approach has remained the de-facto approach despite noteworthy efforts by several researchers to develop more nuanced cultural models of self, such as Gabriel and Gardner (1999) , Kashima and Hardie (2000) and Harb and Smith (2008) . However, interestingly, most of these models nuanced only interdependence and kept independence as a unitary dimension. A few models did acknowledge different aspects of the autonomy implied by independence (e.g., Singelis et al., 1995 ; Triandis and Gelfand, 1998 ; Kagitcibasi, 2005 ), but, in general, independence has been viewed as a monolithic concept in contrast to a more diversified view of interdependence. At the same time, research conducted looking at the different forms of interdependence demonstrates the value of finer-grained approaches to cultural constructs. Campos and Kim (2017) , for example, compared the types of collectivism found in East Asian and Latin American cultures. Although both cultural regions encourage an interdependent view of the self, how interdependence is maintained in relationships is quite different. Similarly, Vignoles et al. (2016) deconstructed both independence and interdependence into their constituent facets and developed a model that distinguishes between different ways of being independent and interdependent across seven different dimensions of functioning (e.g., making decisions, looking after oneself, and communicating with others). The seven dimensions are bipolar in nature, each having an independent pole and an interdependent pole. Initial application of the survey in over 30 countries showed that the seven dimensions did not cluster together into a higher-order dimension of independence and interdependence. Therefore, the conceptualization promoted by Singelis’s measure does not accurately and sufficiently characterize cultural variation in self-construal. Instead, as research by Vignoles et al. (2016) and others suggests, different ways of being independent and interdependent are valued in different cultures. In the current set of studies, we build and expand on this work, testing not only if there are different ways of being independent in different cultures but also if there are psychological implications associated with being or not being independent in ways prescribed by one’s culture.

Whereas previous studies have linked independence, as a unidimensional single factor construct, to self-esteem and life satisfaction, in the current studies, we examine the notion of independence to determine if different aspects of independence are associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction in different cultures. Previous studies found a pancultural explanation, but using a more nuanced approach, we predicted that more cultural differences would emerge. We suggest that it is not independence as a large global concept that predicts self-esteem and, indirectly, life satisfaction, but rather, feeling independent in culturally appropriate ways is a signal that one’s way of being oneself fits in and is valued in one’s context.

Overview of the Current Research

The current research is made up of two studies. In Study 1, we sought to confirm that the previously found relationship between the single-factor measure of independent self-construal typically used in the literature (i.e., Singelis, 1994 ), self-esteem, and life satisfaction would hold true in multiple cultures, even cultures that have previously received scant attention in empirical research.

In Study 2, we used Vignoles et al. (2016) model of self-construal to explore further the relationship between independence, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. Using samples from two cultures (the United States and Romania), we examined whether treating independence as a multifaceted construct would reveal considerable variability in the meaning of independence across cultures as well as the implications of different ways of being independent on psychological outcomes such as life satisfaction.

Study 1: The Relationship Between Unidimensional Independence, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction in Four Cultures

The aim of Study 1 was to test the replicability of previous findings on the link between independence and life satisfaction, mediated by increased self-esteem ( Kwan et al., 1997 ) in cultures that have previously received little empirical attention. To this end, we collected data from three continents and four countries varying on the individualism vs. collectivism index ( Hofstede et al., 2010 ): the United States, 91; Hungary, 80; Japan, 46; and Romania, 30. In addition to the Western individualistic culture (the United States) and the East-Asian collectivistic culture, which have received considerable attention in previous culture research, we therefore included in our study two understudied Eastern European culture – one individualistic (Hungary) and one collectivistic (Romania). Both Hungary and Romania are ex-socialist countries and the socialist regimes strongly promoted collectivism. However, in Hungary, “individualism which was suppressed or kept under control surfaced itself with ‘double strength’ after the political changes when celebrating individualism became the norm ( Fülöp et al., 2019 , p. 86).” The research reviewed and conducted by Fülöp et al. (2019) suggests that Hungarians, both adults and adolescents, are characterized by high levels of independence. In Romania, instead, the struggle to shake off the legacies of the past regime lead to what Gavreliuc (2011) has termed “autarchic individualism,” a rather ambivalent culture, at the same time individualistic and collectivistic. Mixed results were obtained in various studies using measures of independence, some showing high levels of independence, others low or medium level of independence, irrespective of age ( Gavreliuc, 2012 ; see also David, 2015 ; Moza, 2018 for reviews). However, David (2015) concluded that a consistent tendency toward independence can be seen among the young and educated (i.e., students). Irrespective of actual levels of independence, independences still has a positive relationship with self-esteem and well-being as has been documented in previous literature. Therefore, we predicted that the relationship between independence and life satisfaction, mediated through self-esteem, would be culturally invariant.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure.

Participants were 736 undergraduate students, recruited via convenience sampling, from universities in the United States, Romania, Japan, and Hungary. They took part in the study for course credit. The sample consisted of 164 United States (72.6% females; M age = 20.17, SD age = 3.58), 199 Hungarian (86.4% females; M age = 23.83, SD age = 7.47), 277 Romanian (79.8% females; M age = 21.83, SD age = 4.80), and 96 Japanese (44.8% females; M age = 18.97, SD age = 1.03) students.

Independent and interdependent self-construals were measured with the popular Singelis (1994) self-construal scale. Fifteen items were used to measure the independent self-construal (e.g., I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects) and 15 items were used to measure the interdependent self-construal (e.g., “I feel good when I cooperate with others”). Participants rated each item on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of independent self-construal ( α = 0.74 for the United States sample; α = 0.72 for the Hungarian sample; α = 0.74 for the Romanian sample, and α = 0.78 for the Japanese sample) and of interdependent self-construal ( α = 0.72 the United States sample; α = 0.88 for the Hungarian sample; α = 0.86 for the Romanian sample, and α = 0.71 for the Japanese sample).

Self-esteem was measured with the Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale. The scale consists of 10 items (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”). Participants rated each item on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher self-esteem ( α = 0.91 for the United States sample; α = 0.72 for the Hungarian sample; α = 0.86 for the Romanian sample, and α = 0.85 for the Japanese sample).

Life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale ( Diener et al., 1985 ). The scale consists of five items (e.g., I am satisfied with my life). Participants rated each item on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher life satisfaction ( α = 0.90 for the United States sample; α = 0.82 for the Hungarian sample; α = 0.79 for the Romanian sample, and α = 0.85 for the Japanese sample).

Demographic information was obtained on age and gender. Subjective socioeconomic status was measured with the MacArthur pictorial scale ( Adler et al., 2000 ). Participants marked their rung in society compared to others in their environment.

Analytic Approach

Data analysis comprised of four distinct stages: (a) computing descriptive statistics, conducting correlation and ANOVA analyses; (b) performing multi-group SEM to test the mediation model shown in Figure 1 ; (c) performing bootstrap procedures to test the indirect effects in the mediation model; and (d) testing the invariance of the mediation model as well as post-hoc slope comparisons to determine the paths that were significantly different in the four samples.

The path model of the relationships between independent and interdependent self-construal, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in all four cultures. In this figure, the values shown are standardized path coefficients; the statistically significant coefficients are shown in bold. Continuous lines represent significant paths in at least one sample ( p < 0.05), whereas the interrupted line represents non-significant path ( p > 0.05). US, United States sample; HU, Hungarian sample; RO, Romanian sample; JP, Japanese sample.

Main analyses were performed using SEM in Amos 20 ( Arbuckle, 2011 ) and the maximum likelihood estimation method. Gender, age, and subjective socioeconomic status were included as covariates. All variables were identified as observed variables. We decided to include subjective socioeconomic status as a control variable due to its high correlations with both self-esteem (e.g., Twenge and Campbell, 2002 ) and life satisfaction (e.g., Anderson et al., 2012 ).

Structural models were evaluated using a constellation of goodness-of-fit indices as recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) , namely the model chi-square, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI – values above 0.95 indicate good fit), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA – values below 0.06 indicate good fit), and the Standardized Root Mean-square Residual (SRMR – values below 0.08 indicate good fit).

To test the hypothesized mediating effects of self-esteem in the link between self-construals and life satisfaction in a SEM framework, we analyzed the indirect effects of self-construals on life satisfaction using bootstrap functions with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals. We used Zhao et al. (2010) mediation typology to distinguish between: (a) complimentary mediation where both the mediated and direct effect exist and point in the same direction, (b) competitive mediation where both mediated and direct effect exist but point in opposite directions, (c) indirect-only mediation where mediation exists but there is no direct effect (d) direct-only non-mediation where only a direct effect exists, and (e) no-effect non-mediation where neither direct nor indirect effect exist.

To test the invariance of the model within the multigroup modeling framework, we constrained the paths of the model to be equal across the four groups and compared this restricted model to a model in which the paths were freely estimated. We examined the change in χ 2 index when cross-group constraints were imposed on the model. In addition, we used ΔCFI as a comparative index, because Δ χ 2 can be affected by sample size ( Cheung and Rensvold, 2002 ). A significant Δ χ 2 and/or a value of ΔCFI smaller than or equal to −0.01 indicates that the fit of the restricted model was significantly worse than the fit of the nonrestricted model, in which case the paths of the model differ significantly across the four groups ( Cheung and Rensvold, 2002 ). The test of the differences between the four groups was performed by using the “Group Differences” tool within the “Stats Tools Package” ( Gaskin, 2016 ). A significant z -score indicated significant differences between the groups.

Measurement Invariance

Measurement invariance was tested in a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Specifically, we tested and established configural, metric, and scalar invariance of each of the three scales. We used the criteria suggested by Chen (2007) to evaluate model fit: ΔCFI smaller than −0.01, ΔRMSEA smaller than 0.015, and ΔSRMR smaller than 0.030. Initial confirmatory analyses yielded small values in the case of discrepancy indices (i.e., CFI and TLI), while fit indices based on residuals (i.e., RMSEA and SRMR) indicated good fit. Based on the conclusions formulated by Kenny et al. (2015) , we computed the RMSEA of the null model (i.e., nullRMSEA index) to investigate whether discrepancy indices are adequate for our confirmatory models. Kenny et al. (2015) concluded that discrepancy indices are not valid indicators of fit when the nullRMSEA index is too small (i.e., values below 0.158). The results of the tests of measurement invariance for the three scales in Study 1 are presented in Table 1 .

Tests of measurement invariance for the scales in Study 1.

| Scale/model | CFI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR | nullRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Construal Scale | 0.134 | ||||||

| Configural invariance | ⱡ | 0.025 (0.022–0.027) | 0.06 | ⱡ | -- | -- | -- |

| Metric invariance | ⱡ | 0.027 (0.025–0.029) | 0.08 | ⱡ | 0.021 | 0.02 | -- |

| Scalar invariance | ⱡ | 0.028 (0.026–0.030) | 0.10 | ⱡ | 0.022 | 0.02 | -- |

| Self-Esteem Scale | 0.315 | ||||||

| Configural invariance | 0.968 | 0.031 (0.024–0.037) | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Metric invariance | 0.964 | 0.032 (0.025–0.038) | 0.05 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.02 | -- |

| Scalar invariance | 0.954 | 0.035 (0.029–0.041) | 0.08 | 0.012 | 0.003 | 0.03 | -- |

| SWL scale | 0.456 | ||||||

| Configural invariance | 0.994 | 0.038 (0.021–0.054) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Metric invariance | 0.986 | 0.039 (0.011–0.065) | 0.02 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.01 | -- |

| Scalar invariance | 0.975 | 0.050 (0.036–0.064) | 0.05 | 0.011 | 0.110 | 0.03 | -- |

N = 736; United States sample n = 164; Hungarian sample n = 199; Romanian sample n = 277; Japanese sample n = 96; ⱡ not valid indicators of fit when the nullRMSEA index is too small (i.e., values below 0.158, Kenny et al., 2015 ).

Descriptive statistics and the results of one-way ANOVA with post-hoc comparisons between the four cultural samples for the variables in the study are presented in Table 2 .

Results of one-way ANOVA with post-hoc comparisons between the four cultural groups for the variables in the Study 1 model.

| Variable | One-way ANOVA | comparisons | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | HU | RO | JP | US vs. HU | US vs. RO | US vs. JP | HU vs. RO | HU vs. JP | RO vs. JP | ||||||

| IND SC | 4.91 | 0.68 | 4.89 | 0.64 | 5.08 | 0.61 | 4.26 | 0.75 | 37.11 | >0.05 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| INTER SC | 4.88 | 0.63 | 4.37 | 0.79 | 4.76 | 0.74 | 4.62 | 0.64 | 18.31 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.05 | >0.05 |

| SE | 3.76 | 0.79 | 3.49 | 0.73 | 3.91 | 0.59 | 3.20 | 0.74 | 30.86 | <0.01 | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | =0.01 | <0.001 |

| LS | 4.78 | 1.32 | 4.53 | 1.18 | 4.88 | 1.01 | 3.94 | 1.31 | 16.87 | >0.05 | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.01 | =0.001 | <0.001 |

IND SC, independent self-construal; INTER SC, interdependent self-construal; SE, self-esteem; LS, life satisfaction; US, American sample; HU, Hungarian sample; RO, Romanian sample; JP, Japanese sample; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; p , p value of the post hoc comparisons using the Hochberg’s GT2 test for independent self-construal and Games-Howell test for the other three. Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance for independent self-construal was not statistically significant; we therefore used so Hochberg’s GT2 test for post-hoc comparisons, because we had unequal groups and equal variances on this variable. For the other three variables, Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance was statistically significant; we considered them as having unequal variances and therefore used the Games-Howell test for post-hoc comparisons.

Table 3 presents the bivariate correlations between the variables in each cultural group.

Bivariate correlations between all variables in the study in all four cultural samples in Study 1.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American sample ( = 164) | ||||||

| 1. Independent self-construal | 1 | |||||

| 2. Interdependent self-construal | 0.130 | 1 | ||||

| 3. Self-esteem | 0.308 | −0.089 | 1 | |||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 0.271 | 0.095 | 0.670 | 1 | ||

| 5. Age | 0.066 | 0.199 | 0.097 | 0.094 | 1 | |

| 6. Gender | 0.140 | −0.005 | 0.108 | 0.054 | −0.157 | 1 |

| 7. SSES | 0.072 | −0.087 | 0.152 | 0.265 | −0.105 | 0.069 |

| Hungarian sample ( = 199) | ||||||

| 1. Independent self-construal | 1 | |||||

| 2. Interdependent self-construal | −0.068 | 1 | ||||

| 3. Self-esteem | 0.356 | −0.184 | 1 | |||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 0.192 | 0.027 | 0.585 | 1 | ||

| 5. Age | −0.009 | −0.069 | 0.017 | −0.108 | 1 | |

| 6. Gender | 0.054 | 0.052 | −0.156 | −0.013 | −0.031 | 1 |

| 7. SSES | 0.052 | 0.056 | 0.165 | 0.250 | −0.071 | −0.003 |

| Romanian sample ( = 277) | ||||||

| 1. Independent self-construal | 1 | |||||

| 2. Interdependent self-construal | 0.072 | 1 | ||||

| 3. Self-esteem | 0.402 | −0.273 | 1 | |||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 0.151 | −0.010 | 0.387 | 1 | ||

| 5. Age | 0.101 | −0.039 | 0.064 | −0.167 | 1 | |

| 6. Gender | 0.001 | 0.208 | −0.005 | 0.122 | −0.065 | 1 |

| 7. SSES | 0.019 | −0.162 | 0.083 | 0.182 | −0.001 | −0.031 |

| Japanese sample ( = 99) | ||||||

| 1. Independent self-construal | 1 | |||||

| 2. Interdependent self-construal | −0.261 | 1 | ||||

| 3. Self-esteem | 0.402 | −0.177 | 1 | |||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 0.168 | 0.113 | 0.379 | 1 | ||

| 5. Age | −0.014 | −0.070 | 0.134 | 0.152 | 1 | |

| 6. Gender | −0.156 | 0.182 | −0.128 | 0.013 | −0.044 | 1 |

| 7. SSES | −0.014 | −0.009 | 0.033 | 0.206 | 0.003 | 0.009 |

SSES, subjective socio-economic status.

Based on the results of the preliminary analyses, we initially tested the model presented in Figure 1 without a path from interdependence to life satisfaction because the relationship was not statistically significant in any of the four cultures. The fit indices of this initial model were modest [ χ 2 (40) = 72.51, p = 0.001; CFI = 0.931; SRMR = 0.073, RMSEA = 0.033]. Next, we added an additional path from interdependence to life satisfaction in a second model based on both previous empirical findings (e.g., Kwan et al., 1997 ; Singelis et al., 1999 ) and on methodological recommendations ( Kline, 2016 ). This model (see Figure 1 ) showed improved fit over the initial model [ χ 2 (40) = 54.07, p = 0.068; CFI = 0.970; SRMR = 0.067, RMSEA = 0.022].

The model was not the same across our four cultures. The results of slope comparisons are shown in Table 4 .

Differences in the paths of the model between the four cultural samples in Study 1.

| Path in the model | Sample | Statistical comparisons between model paths in the four samples | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | HU | RO | JP | US vs. HU | US vs. RO | US vs. JP | HU vs. RO | HU vs. JP | RO vs. JP | |||||

| Epc | Epc | Epc | Epc | |||||||||||

| IND SC → SE | 0.35 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 0.41 | 0.000 | 0.38 | 0.000 | 0.44 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.30 |

| INTER SC → SE | −0.18 | 0.051 | −0.15 | 0.012 | −0.25 | 0.000 | −0.07 | 0.543 | 0.27 | −0.74 | 0.77 | −1.43 | −0.65 | −1.57 |

| SE → LS | 1.07 | 0.000 | 0.98 | 0.000 | 0.71 | 0.000 | 0.64 | 0.000 | −0.65 | −2.50 | −2.11 | −1.86 | 1.66 | 0.33 |

| INTER SC → LS | 0.33 | 0.005 | 0.18 | 0.034 | 0.14 | 0.062 | 0.41 | 0.030 | −1.07 | −1.34 | 0.37 | −1.43 | −1.13 | −1.31 |

| INDSC → LS | 0.06 | 0.616 | −0.05 | 0.636 | −0.02 | 0.866 | 0.15 | 0.395 | −0.69 | −0.49 | 0.45 | 0.24 | −0.97 | −0.83 |

IND SC, independent self-construal; INTER SC, interdependent self-construal; SE, self-esteem; LS, life satisfaction; US, United States sample; HU, Hungarian sample; RO, Romanian sample; JP, Japanese sample; Epc, estimate path coefficient.

The relationship between self-esteem and life satisfaction was significantly stronger in the United States and Hungarian samples compared to the Romanian and Japanese samples. We found evidence for an indirect-only mediation between independent self-construal, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in all four samples. In other words, independent self-construal has no direct relationship with life satisfaction but only a relationship mediated by self-esteem. In addition, we found evidence for direct-only nonmediation in our United States sample, competitive mediation in our Hungarian sample, indirect-only mediation in our Romanian sample, and no-effect nonmediation in our Japanese sample. The direct, indirect, and total effects of independent and interdependent self-construals on life satisfaction in the four cultural samples are presented in Table 5 .

Direct, indirect, and total effects of independent and interdependent self-construals on life satisfaction in all four cultural samples in Study 1.

| Variable | Direct effects | Indirect effects | Total effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (SE) C.I. | (SE) C.I. | (SE) C.I. | (SE) C.I. | (SE) C.I. | (SE) C.I. | |

| American sample | ||||||

| IND SC | 0.06 (0.12) [−0.16, 0.29] | 0.03 (0.06) [−0.08, 0.15] | 0.37 (0.10) [0.18, 0.58] | 0.19 (0.05) [0.10, 0.29] | 0.43 (0.14) [0.15, 0.72] | 0.22 (0.07) [0.08, 36] |

| INTER SC | 0.33 (0.12) [0.09, 0.57] | 0.16 (0.06) [0.05, 0.27] | −0.19 (0.10) [−0.40, 0.01] | −0.09 (0.05) [−0.20, 0.00] | 0.14 (0.16) [−0.17, 0.45] | 0.07 (0.08) [−0.08, 0.22] |

| Hungarian sample | ||||||

| IND SC | −0.05 (0.11) [−0.27, 0.16] | −0.03 (0.06) [−0.15, 0.09] | 0.39 (0.08) [0.24, 0.58] | 0.21 (0.04) [0.13, 0.31] | 0.34 (0.12) [0.09, 0.58] | 0.18 (0.07) [0.05, 0.31] |

| INTER SC | 0.18 (0.09) [0.01, 0.35] | 0.12 (0.06) [0.01, 0.23] | −0.14 (0.06) [−0.28, −0.03] | −0.10 (0.04) [−0.18, −0.02] | 0.03 (0.10) [−0.17, 0.24] | 0.02 (0.07) [−0.11, 0.16] |

| Romanian sample | ||||||

| IND SC | −0.02 (0.10) [−0.21, 0.18] | −0.01 (0.06) [−0.12, 0.11] | 0.29 (0.06) [0.19, 0.42] | 0.18 (0.03) [0.12, 0.25] | 0.27 (0.10) [0.09, 0.46] | 0.17 (0.06) [0.05, 0.27] |

| INTER SC | 0.14 (0.08) [−0.02, 0.30] | 0.11 (0.06) [−0.01, 0.22] | −0.18 (0.04) [−0.26, −0.11] | −0.13 (0.03) [−0.20, −0.08] | −0.04 (0.08) [−0.20, 0.12] | −0.03 (0.06) [−0.14, 0.09] |

| Japanese sample | ||||||

| IND SC | 0.15 (0.18) [−0.22, 0.51] | 0.09 (0.10) [−0.13, 0.28] | 0.24 (0.10) [0.09, 0.48] | 0.14 (0.05) [0.06, 0.27] | 0.39 (0.18) [0.04, 0.74] | 0.22 (0.10) [0.02, 0.41] |

| INTER SC | 0.41 (0.21) [0.03, 0.83] | 0.20 (0.10) [0.01, 0.39] | −0.04 (0.08) [−0.23, 0.09] | −0.02 (0.04) [−0.11, 0.05] | 0.37 (0.22) [−0.05, 79] | 0.18 (0.10) [−0.03, 0.37] |

IND SC, independent self-construal; INTER SC, interdependent self-construal; B(SE) and β (SE) represent unstandardized (B) and standardized ( β ) coefficients followed by standard errors; C.I. are presented in square brackets and represent 95% bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals; statistical significance (i.e., a bootstrap approximation obtained by constructing two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals) is indicated by superscripts.

Study 1 results replicated previous findings ( Kwan et al., 1997 ; Chang et al., 2011 ; Duan et al., 2013 ; Yu et al., 2016 ), showing that unidimensional independence and life satisfaction are positively and indirectly related, by self-esteem mediating the relationship. A potential explanation of this mediation mechanism is provided by Markus and Kitayama (1991) , who argued that individuals’ own evaluation of their self-worth, which is strongly connected with their life satisfaction, is dependent on the cultural standards encompassed in their self-construal. Our results confirmed the invariance of this mediated relationship in individualistic and collectivistic cultures that have received little attention in past empirical research, such as Hungary and Romania, in addition to well-studied cultures such as the United States and Japan.

Study 2: Dissecting Independence—An Analysis of Aspects of Independence Associated With Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction in the United States and Romania

In Study 2, we focused more in depth on two of the countries from Study 1 – the United States and Romania. In Study 1, we established that in both of these cultures, unidimensional independence predicts life satisfaction, and this is partially mediated through self-esteem. Our intent for Study 2 was to see if taking a more nuanced approach and using a new multidimensional measure of independence would illuminate differences between the two cultures.

Previous ethnographic research conducted with European-American parents in different socioeconomic stratums of New York City found that all of the American parents, regardless of family income, embraced an independent view of the self ( Kusserow, 1999 ), but independence meant something very different for lower- and higher-class families. For families of lower SES that had more daily struggle, independence was associated with being tough and self-reliant, but for families of higher SES, independence was associated with developing a unique sense of self. We expected these same types of results at the country level. Indeed, consistent with this theorizing, previous research has shown that in American culture, there is a strong emphasis on self-expression and personal uniqueness ( Kim and Markus, 1999 ; Kim and Sherman, 2007 ) to the extent that American individualism has been called “expressive individualism” ( Bellah et al., 1985 ). In Romanian culture, although uniqueness is also valued, other characteristics of hard independence, such as self-reliance, consistency, and self-direction are equally valued as uniqueness ( Gavreliuc and Ciobotă, 2013 ). Thus, we predicted that in Romania, a country that is poorer and has dealt with much more upheaval and uncertainty in its recent past (including the collapse of communism and a tumultuous transition to a democracy), aspects of independence that would be valued and associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction would be related to being tough and self-reliant. On the other hand, we expected that in the United States, a relatively wealthier and more stable environment, aspects of independence associated with being unique and standing out would be associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction.

Data was collected from a convenience sample of 370 participants. They were 203 Romanian and 167 undergraduate psychology students in the United States who received course credit or extra credit for participating in the study. In the Romanian sample, the mean age was 19.80 years ( SD = 1.41), 66.5% were females. In the United States sample, 11 participants were excluded from the analyses because they were not fully enculturated in the United States culture (i.e., they were born in another country and immigrated in the United States after they were 5 years old). The mean age of the remaining 156 participants included in the analyses was 18.71 years ( SD = 1.27), and 64.7% were females.

Independent and interdependent self-construals were measured with the 62-item version of the seven-factor self-construal scale recently developed by Vignoles et al. (2016) . Participants indicated the extent to which each of 62 items described them on a nine-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 9 (exactly). The scale includes seven sub-scales reflecting ways of viewing the self as independent of others or interdependent with others with respect to different domains of functioning. Specifically, (1) self-containment vs. connectedness to others with respect to experiencing the self (e.g., “Your happiness is independent from the happiness of your family”; α = 0.70 for the United States sample; α = 0.75 for the Romanian sample), (2) self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence with respect to making decisions (e.g., “You usually decide on your own actions, rather than follow others’ expectations”; α = 0.77 for the United States sample; α = 0.76 for the Romanian sample), (3) difference vs. similarity reflects the ways of viewing the self as independent vs. interdependent with respect to defining the self (e.g., “You see yourself as different from most people”; α = 0.83 for the United States sample; α = 0.76 the Romanian sample), (4) self-reliance vs. dependence on others with respect to looking after oneself (e.g., “You prefer to rely completely on yourself rather than depend on others”; α = 0.79 for the United States sample; α = 0.76 the Romanian sample), (5) consistency vs. variability with respect to moving between contexts (e.g., “You behave the same way at home and in public”; α = 0.89 for the United States sample; α = 0.81 for the Romanian sample), (6) self-expression vs. harmony with respect to communicating with others (e.g., “You prefer to say what you are thinking, even if it is inappropriate for the situation”; α = 0.78 for the United States sample; α = 0.74 for the Romanian sample), and (7) self-interest vs. commitment to others with respect to dealing with conflicting interests (e.g., “Your own success is very important to you, even if it disrupts your friendships”; α = 0.70 for the United States sample; α = 0.76 for the Romanian sample). Each sub-scale is composed of a certain number of items tapping the independent way of viewing the self and a number of items tapping the interdependent way. Items for both the independent pole and for the interdependent pole of each sub-scale were positively phrased, but conceptual reversals of each other (e.g., consistency: “You behave the same way at home and in public” vs. variability: “You see yourself differently in different social environments”). Items tapping the interdependent self-views were reverse coded. Higher scores on each dimension indicate a higher independent view of the self and lower scores a higher interdependent self-view.

As in Study 1, self-esteem was measured with Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale ( α = 0.90 for the United States sample; α = 0.88 for the Romanian sample) and life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale ( Diener et al., 1985 ; α = 0.88 for the United States sample; α = 0.89 for the Romanian sample). Also, as in Study 1, we collected data on age, gender, and subjective socio-economic status.

The analytic approach was similar to the approach used in Study 1, except for the fact that the model we tested is based on seven-dimensional self-construal and includes only two samples.

Measurement invariance was tested in the same way as for the scales in Study 1. The results of the tests of measurement invariance for the three scales in Study 2 are presented in Table 6 . Both metric and scalar measurement invariance was achieved, allowing for cross-cultural comparisons using these measures.

Tests of measurement invariance for the scales in Study 2.

| Scale/model | CFI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR | nullRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Construal Scale | 0.127 | ||||||

| Configural invariance | ⱡ | 0.043 (0.041–0.045) | 0.08 | ⱡ | -- | -- | -- |

| Metric invariance | ⱡ | 0.044 (0.042–0.045) | 0.09 | ⱡ | 0.001 | 0.01 | -- |

| Scalar invariance | ⱡ | 0.044 (0.042–0.046) | 0.10 | ⱡ | 0.000 | 0.01 | -- |

| Self-Esteem Scale | 0.312 | ||||||

| Configural invariance | 0.960 | 0.052 (0.039–0.065) | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Metric invariance | 0.956 | 0.051 (0.039–0.064) | 0.06 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.00 | -- |

| Scalar invariance | 0.957 | 0.050 (0.038–0.063) | 0.07 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01 | -- |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | 0.515 | ||||||

| Configural invariance | 0.983 | 0.044 (0.000–0.089) | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Metric invariance | 0.981 | 0.040 (0.001–0.084) | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.00 | -- |

| Scalar invariance | 0.981 | 0.040 (0.001–0.086) | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.110 | 0.01 | -- |

N = 359; United States sample n = 156; Romanian sample n = 203; ⱡ not valid indicators of fit when the nullRMSEA index is too small (i.e., values below 0.158, Kenny et al., 2015 ).

Descriptive statistics and the results of t -tests for differences between the United States and Romanian samples for the variables in the study are presented in Table 7 .

Means, SD, and t -tests for differences between the United States and Romanian samples for the variables in the Study 2.

| Variable | Mean ( ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| US | RO | ||

| 1. Self-containment vs. connectedness to others | 4.39 (1.04) | 4.55 (1.11) | −1.37 |

| 2. Self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence | 5.52 (1.15) | 6.17 (1.32) | −4.83 |

| 3. Difference vs. similarity | 5.93 (1.25) | 6.55 (1.24) | −4.69 |

| 4. Self-reliance vs. dependence on others | 5.47 (1.24) | 6.35 (1.36) | −6.32 |

| 5. Consistency vs. variability | 5.10 (1.61) | 5.78 (1.55) | −4.04 |

| 6. Self-expression vs. harmony | 4.74 (1.23) | 5.47 (1.33) | −5.32 |

| 7. Self-interest vs. commitment to others | 4.64 (1.02) | 4.75 (1.34) | −0.80 |

| 8. Self-esteem | 3.01 (0.54) | 3.04 (0.53) | −0.47 |

| 9. Life satisfaction | 4.73 (1.26) | 4.67 (1.34) | −0.41 |

US, American sample; RO, Romanian sample.

Table 8 presents the bivariate correlations between the variables in each sample.

Bivariate correlations between all variables in Study 2 by each culture.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cont_Conn | - | 0.394 | 0.007 | 0.207 | 0.032 | 0.201 | 0.378 | 0.007 | −0.165 | −0.096 | −0.213 | 0.039 |

| 2. Dir_Rec | 0.406 | - | 0.300 | 0.460 | 0.034 | 0.387 | 0.276 | 0.023 | −0.162 | 0.084 | −0.141 | −0.610 |

| 3. Diff_Sim | 0.152 | 0.390 | - | 0.243 | 0.304 | 0.344 | −0.087 | 0.354 | 0.171 | −0.034 | 0.030 | 0.088 |

| 4. Rel_Dep | 0.204 | 0.523 | 0.336 | - | −0.021 | 0.072 | 0.132 | −0.058 | −0.155 | 0.101 | −0.026 | −0.100 |

| 5 Cons_Var | 0.221 | 0.163 | 0.126 | 0.254 | - | 0.199 | −0.108 | 0.358 | 0.212 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.133 |

| 6. Exp_Har | 0.234 | 0.327 | 0.332 | 0.421 | 0.363 | - | 0.349 | 0.208 | 0.158 | −0.046 | −0.023 | 0.033 |

| 7. Int_Comm | 0.476 | 0.392 | 0.107 | 0.254 | 0.043 | 0.260 | - | −0.034 | −0.090 | −0.167 | −0.097 | 0.043 |

| 8. Self-esteem | 0.100 | 0.238 | 0.218 | 0.352 | 0.427 | 0.390 | 0.153 | - | 0.706 | −0.014 | −0.124 | 0.456 |

| 9. Life satisfaction | −0.149 | 0.051 | 0.168 | 0.125 | 0.285 | 0.190 | −0.142 | 0.615 | - | −0.003 | 0.041 | 0.479 |

| 10. Age | −0.003 | 0.159 | 0.084 | 0.063 | 0.032 | −0.019 | −0.019 | 0.069 | 0.033 | - | 0.121 | 0.031 |

| 11. Gender | −0.158 | −0.186 | −0.049 | 0.016 | 0.042 | −0.061 | −0.133 | 0.094 | 0.128 | −0.077 | - | −0.098 |

| 12. SSES | −0.021 | 0.005 | 0.045 | 0.130 | 0.153 | 0.187 | 0.101 | 0.350 | 0.413 | 0.058 | 0.052 | - |

The correlation coefficients of United States sample are presented on the top-right side of the diagonal; the correlation coefficients of Romanian sample are shown on the down-left side of the diagonal; Diff_Sim, Difference vs. Similarity; Cont_Conn, Self-containment vs. Connection to others; Dir_Rec, Self-direction vs. Receptiveness to influence; Rel_Dep, Self-reliance vs. Dependence on others; Exp_Har, Self-expression vs. Harmony; Int_Comm, Self-interest vs. Commitment to others; Cons_Var, Consistency vs. Variability; SSES, Subjective Socio-economic Status; Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the United States sample are presented on the left side and for the Romanian sample, on the right side.

We initially built a path model, which included all the paths from the self-construal dimensions to self-esteem and to life satisfaction for which the correlations were statistically significant in at least one sample. This initial model also included all the significant correlations between the different self-construal dimensions. The model showed an excellent fit [ χ 2 = 30.74, df = 22, p = 101; CFI = 0.990; SRMR = 0.041; RMSEA = 0.033 CI 10% (0.000, 0.059)]; however, the direct paths from the self-construal dimensions of self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence and self-interest vs. commitment to others and self-esteem, and between the self-construal dimension of difference vs. similarity and life satisfaction were non-significant in both cultural groups and were thus removed in the subsequent model. The modified model ( Figure 2 ) had an excellent fit, slightly improved over the initial model [ χ 2 = 39.52, df = 32, p = 0.169; CFI = 0.991; SRMR = 0.040; RMSEA = 0.026 CI 10% (0.000, 0.049)]. As predicted, the model was different across cultures.

Path model of the relationships between self-construal dimensions, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. In this figure, the values shown are standardized path coefficients. The paths that were not statistically significant in at least one sample are not showed; the statistically significant coefficients are shown in bold; US, United States sample; RO, Romanian sample.

The differences in the paths of the model between the two cultural samples are shown in Figure 2 (see also Table 9 ).

Differences in the paths of the model between the two cultural samples in Study 2.

| Path in the model | Romanian sample | U.S. sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epc | Epc | ||||

| Difference vs. similarity → self-esteem | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.276 | −1.921 |

| Self-reliance vs. dependence on others → self-esteem | −0.035 | 0.233 | 0.063 | 0.013 | 2.530 |

| Consistency vs. variability → self-esteem | 0.072 | 0.002 | 0.098 | 0.000 | 0.826 |

| Self-expression vs. harmony → self-esteem | 0.032 | 0.292 | 0.059 | 0.028 | 0.687 |

| Self-esteem → life satisfaction | 1.375 | 0.000 | 1.432 | 0.000 | 0.282 |

| Self-containment vs. connectedness to others → life satisfaction | −0.159 | 0.027 | −0.141 | 0.045 | 0.180 |

| Self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence → life satisfaction | −0.166 | 0.012 | 0.049 | 0.408 | 2.427 |

| Self-expression vs. harmony → life satisfaction | 0.127 | 0.009 | −0.008 | 0.885 | −1.614 |

| Self-interest vs. commitment to others → life satisfaction | −0.038 | 0.610 | −0.213 | 0.000 | −1.849 |

Epc, estimate path coefficient; z , the Z (Fisher) test.

Next, we tested the indirect effects of the self-construal dimensions on life satisfaction through self-esteem (indirect-only mediation, where mediation exists but there is no direct effect, Zhao et al., 2010 ). In the United States sample, two self-construal dimensions had statistically significant positive indirect effects on life satisfaction, namely difference vs. similarity [ B = 0.15(0.049), 95% CI (0.06, 0.25), p < 0.01; β = 0.15(0.049), 95% CI (0.06, 0.25), p < 0.01] and consistency vs. variability ( B = 0.10(0.039), 95% CI [0.03, 0.18], p < 0.01; β = 0.13(0.049), 95% CI [0.04, 0.33], p < 0.01). In the Romanian sample, there were three self-construal dimensions that had positive indirect effects on life satisfaction, namely self-reliance vs. dependence on others ( B = 0.09(0.039), 95% CI [0.01, 0.17], p < 0.05; β = 0.09(0.040), 95% CI [0.01, 0.17], p < 0.05), consistency vs. variability ( B = 0.14 (0.037), 95% CI [0.07, 0.22], p < 0.001; β = 0.16(0.042), 95% CI [0.09, 0.25], p < 0.001), and self-expression vs. harmony ( B = 0.09 (0.041), 95% CI [0.00, 0.17], p < 0.05; β = 0.09(0.041), 95% CI [0.00, 0.17], p < 0.05).

We then tested direct-only nonmediation, where only a direct effect exists between self-construal dimensions and life satisfaction, in each cultural sample. As shown in Figure 2 , four self-construal dimensions predicted life satisfaction directly. Only one of these dimensions predicted life satisfaction positively, and only in the United States sample, and that is self-expression vs. harmony [ B = 0.13(0.057), 95% CI (0.01, 0.24), p < 0.05; β = 0.13(0.058), 95% CI (0.01, 0.24), p < 0.05]. The other predictors were negative. This means that a higher level of the independent pole of a self-construal dimension was associated with lower life satisfaction, whereas a higher level of the interdependent pole of the same dimension was associated with higher life satisfaction. There was only one dimension that predicted life satisfaction similarly, and negatively, in both cultures, namely self-containment vs. connectedness to others [the United States sample: B = −0.16 (0.082), 95% CI (−0.32, −0.01), p < 0.05; β = −0.13(0.069), 95% CI (−0.27, −0.00), p < 0.05; Romanian sample: B = −0.14 (0.076), 95% CI (−0.30, −0.00), p < 0.05; β = −0.12(0.062), 95% CI [−0.24, −0.00], p < 0.05). The dimension self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence predicted life satisfaction negatively only in the United States sample [ B = −0.17 (0.067), 95% CI (−0.30, −0.03), p < 0.05; β = −0.16(0.063), 95% CI (−0.28, −0.03), p < 0.05]. The dimension self-interest vs. commitment to others predicted life satisfaction negatively only in the Romanian sample [ B = −0.21 (0.056), 95% CI (−0.31, −0.09), p = 0.001; β = −0.22(0.059), 95% CI (−0.32, −0.09), p = 0.001].