Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 11, Issue 1

- Systematic review of global clinical practice guidelines for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Meng Zhang 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4884-4248 Jun Tang 1 , 2 ,

- Yang He 1 , 2 ,

- Wenxing Li 1 , 2 ,

- Zhong Chen 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0408-1288 Tao Xiong 1 , 2 ,

- Yi Qu 1 , 2 ,

- Youping Li 3 ,

- Dezhi Mu 1 , 2

- 1 Department of Pediatrics , Sichuan University West China Second University Hospital , Chengdu , China

- 2 Key Laboratory of Obstetrics & Gynecologic and Pediatric Diseases and Birth Defects of the Ministry of Education , Sichuan University , Chengdu , China

- 3 Chinese Evidence-Based Medicine Center , Sichuan University West China Hospital , Chengdu , China

- Correspondence to Professor Jun Tang; tj1234753{at}sina.com

Objective Hyperbilirubinemia is one of the most common clinical symptoms in newborns. To improve patient outcomes, evidence-based and implementable guidelines are required. However, clinical guidelines may vary in quality, criteria and recommendations among regions and countries. In this study, we aimed to systematically assess the quality of guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE)-II instrument and summarise the specific recommendations for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in order to provide suggestions for future guideline development.

Design Systematic review.

Interventions We searched the PubMed, Embase, Medline and guideline databases for relevant articles on 10 April 2020. The studies were screened by two independent reviewers according to our inclusion criteria. Two reviewers independently extracted the descriptive data. Four appraisers assessed the guidelines using the AGREE-II instrument.

Results Our systematic review appraised 12 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. The 12 guidelines achieved an average score of 36%–89%. The guidelines received the highest scores for clarity of presentation and lowest scores for rigour of development. Most recommendations for diagnosis were relatively consistent, but recommendations regarding risk factors, the initiating threshold of treatment and pharmacotherapy varied.

Conclusions Our study revealed that current guidelines vary in the quality of the developing process and are inconsistent with regards to recommendations. Future guidelines should afford more attention to the quality of methodologies in guideline development, and more qualified evidence is needed to standardise the initiating threshold of treatment for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.

- neonatology

- developmental neurology & neurodisability

- protocols & guidelines

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040182

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study is the first English systematic appraisal of guidelines targeted to neonates with hyperbilirubinemia.

The strengths also included the use of the validated Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument and four independent reviewers to minimise subjective bias.

A Chinese-language guideline by the Chinese Pediatric Society was appraised.

The AGREE-II was used to evaluate guidelines with less attention on detailed recommendations.

We only assessed guidelines through the reported literature without the use of additional methods such as contacting guideline developers.

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, characterised by the elevation of total serum bilirubin (TSB), is one of the most common clinical conditions affecting newborns, particularly preterm infants. Hyperbilirubinemia affects approximately 60% of full-term and 80% of preterm neonates. 1 Approximately 10% of newborns are likely to develop clinically significant hyperbilirubinemia requiring close monitoring and treatment. 2 In the early period (0–6 days), neonatal hyperbilirubinemia accounted for 1309.3 deaths per 100 000 livebirths and was the seventh most common cause of neonatal deaths. 3 Effective and timely treatment with phototherapy or exchange transfusion can reduce the occurrence of neurological dysfunction in neonates with hyperbilirubinemia.

Clinical practice guidelines are in place to aid clinical, policy-related and system-related decisions. 4 Guidelines have also been developed to bridge the gap between research and clinical practice. 5 Therefore, guidelines have become increasingly popular in recent years. 6 Although several organisations from different regions have developed clinical practice guidelines, these guidelines may vary widely in quality. 7 8 Moreover, the criteria for diagnosis and treatment in published guidelines vary among regions and countries. 9

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) instrument is used to assess methodological rigour and transparency of a guideline. 10 In this study, we aimed to systematically review and assess the quality of guidelines on neonatal hyperbilirubinemia using the AGREE-II instrument in order to provide suggestions for future guideline development.

Selection criteria

We included clinical practice guidelines produced by local, regional, national or international groups or affiliated governmental organisations for the diagnosis and management of hyperbilirubinemia in newborn infants. The guidelines were included if they met the following criteria: (1) published in English or Chinese language, (2) based on systematic evidence synthesis and containing specific statements to guide decisions regarding hyperbilirubinemia, (3) include recommendations for the diagnosis and/or treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and (4) published between 2000 and 2020, and only the most recent editions of updated guidelines were considered.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed on 10 April 2020. We searched for relevant studies in the PubMed, Embase and Medline databases. In addition, we searched the Guidelines International Network, National Health Service Evidence website, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network website, Turning Research Into Practice Database and Wan fang Database. The titles and abstracts of the searched citations were screened by two independent reviewers (MZ and YH). Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion. The detailed search strategy for PubMed is shown in the online supplemental material .

Supplemental material

Guideline characteristics.

Two independent reviewers (MZ and YH) extracted the general characteristics of the included guidelines: country, founding organisation, year of publication or updating status, method of evidence identification and funding.

Appraisal of guideline quality

Four appraisers (MZ, YH, WL and ZC) independently assessed the selected guidelines using the AGREE-II instrument. The AGREE II is an international, validated and rigorously developed tool to evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. 11 The AGREE II consists of 23 key items organised within six domains (scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability and editorial independence) followed by two global rating items (overall assessment). Each domain points to a unique dimension of guideline quality. 12 Each of the AGREE II items is rated on a 7-point scale (1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree). Domain scores are calculated by summing the scores of the individual items in a domain and by scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain. 12 The score for each domain of each document is calculated as follows: (obtained score−minimal possible score)/(maximal possible score−minimal possible score). 10 All reviewers were trained online using the AGREE training tools. Discrepancies of >3 points were discussed in a consensus meeting.

We extracted descriptive data from the guideline recommendations to identify the consistencies and discrepancies. The recommendations were then summarised according to different items related to the diagnosis and treatment strategies of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia such as the test used for the early prediction and diagnosis, time to start phototherapy and exchange transfusion, recommendation for drug use, criterion for discharge and timing or frequency of follow-up. The intraclass correlation coefficients for the six domains were calculated to assess the reliability of the scores between investigators. The analysis of the reliability study was performed using SPSS V.24.0.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Search results

Figure 1 illustrates the search and guideline selection process. The systematic search retrieved 725 records, of which 701 were excluded after removing duplicates and articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria. Consequently, after the full-text evaluation of the remaining records, 12 additional clinical practice guidelines were excluded for the following reasons: not written in English or Chinese, not original guidelines and not clinical practice guidelines or consensuses. Ultimately, we included 12 clinical practice guidelines from 12 different national or regional organisations.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study selection diagram. GIN, Guidelines International Network; NHS, NationalHealth Service; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; TRIP, TurningResearch Into Practice Database.

General characteristics of the guidelines

Tables 1 and 2 summarise the general characteristics of the included clinical practice guidelines. Twelve clinical practice guideline documents were published by national or regional organisations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia, 13 Canadian Pediatric Society (CPS) Fetus and Newborn Committee, 14 Chinese Pediatric Society (ChPS) Chinese medical Association, 15 Israel Neonatal Society (INS), 16 Italian Society of Neonatology (ISN), 17 Malaysia Health Technology Assessment Section (MaHTAS), 18 NICE in the UK, 19 Norwegian Pediatric Association, 20 Queensland Clinical Guidelines (QCG) in Australia, 21 Spanish Association of Pediatrics (SAP), 22 Swiss Society of Neonatology (SSN) 23 and Turkish Pediatric Association (TPA). 24 Five of these guidelines are new and the others have been updated or reaffirmed. Four guidelines from the USA, 13 Canada, 14 Italy 17 and Switzerland 23 were targeted towards neonates born at >35 weeks of gestation, while the other guidelines covered all preterm and term babies. Six organisations (QCG, 21 CPS, 14 SAP, 22 NICE, 19 INS 16 and MaHTAS 18 reported performing a systematic review and appraisal of the evidence and were explicit about the level of evidence that underpinned their recommendations. Three groups were funded by governmental institutions (QCG, 21 NICE 19 and MaHTAS), 18 one declared no financial support (TPA), 24 and the remainder did not disclose a funding source.

- View inline

General characteristics

Appraisal of guidelines

Table 3 shows the scores for each guideline for the six domains of the AGREE II instrument. The overall quality of the guideline development process varied widely both among guidance documents and within guidance documents among different domains. The average score was 36.3%–89.3%. Most guidelines achieved average scores of <50% in four of the six domains, and only two received an average score of >50%. The highest scores were achieved in the domains of clarity of presentation and the lowest scores were achieved for rigour of development.

Domain scores of the nine guidelines assessed by using the AGREE-II instrument (%)

Domain 1: the mean score for scope and purpose was 88.8%±6.5% and the MaHTAS 18 guideline achieved the highest score at 98.6%. Domain 2: the mean stakeholder involvement score was 47.6%±22.4% and ChPS 15 received the lowest score at 9.7%. Domain 3: the mean score for rigour of development was 31.9%±22.6%. NICE 19 scored the highest for this domain at 85.9% with the most extensive development process, while TPA 24 received the lowest at only 9.9%. Domain 4: the mean score for clarity of presentation was 91.7%±5.7%. For this domain, most of the guidelines obtained a score of >90%. Domain 5: the mean score for applicability was 43.0%±18.9%, with five guidelines scoring <30%. Domain 6: the mean score for editorial independence was 36.8%±36.1%, and four guidelines obtained scores of 0% for this domain. In terms of overall quality, 50% of the guidelines received an average score of >50%. The NICE 19 guidelines received the highest score at 89.3%±5.7%.

Table 4 shows the intraclass correlation coefficients, 95% CIs, and p values for each domain between the four evaluators. The intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.818 to 0.995.

Inter rater reliability study results

Clinical guideline recommendations

Nine guidelines covered risk factors for severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, including maternal and neonatal risk factors. All guidance documents provided recommendations for diagnosis. Tables 5 and 6 show the main risk factors and some example diagnostic strategies for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. The guidelines differed somewhat in their report of risk factors. Nearly all guidelines reported prematurity, exclusive breastfeeding and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency as neonatal risk factors. Cephalohematoma or bruises and male sex were also defined as neonatal risk factors in some guidelines, while NICE 25 stated that the evidence was inconclusive and that the results of most studies revealed no significant association between these factors and hyperbilirubinemia.

Summary of risk factors of severe neonatal jaundice

Summary of recommendations for approaches to diagnosis of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

Visual assessment was recommended as a first step in diagnosis by most organisations, and the guideline of Malaysia 18 specifically mentioned that Kramer’s rule could be widely practiced. All guidelines advocated TSB measurement as the gold standard for detecting and determining the level of hyperbilirubinemia. Non-invasive methods such as a transcutaneous bilirubinometer are accepted by all guidelines. Other methods of detection such icterometers were not recommended by NICE 19 and MaHTAS 18 because there was no good quality evidence to indicate their reliability. In addition, nearly all guidelines recommended additional laboratory tests for babies with prolonged hyperbilirubinemia that could be of value to evaluate and identify the underlying disease. These tests included complete blood counts, blood group compatibility, a direct antiglobulin test, septic workup, urinalysis, urine culture, thyroid functions, G6PD, reticulocyte count and conjugated component of bilirubin.

Table 7 shows the recommendations for the management of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. The key areas included the initiating threshold and details of different types of therapies and care for babies during therapy. The guidelines distinguished treatment scenarios based on the level of hyperbilirubinemia, including phototherapy, exchange transfusion and pharmacotherapy.

Summary of recommendations for approaches to treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

All guidelines discussed the threshold of phototherapy and exchange transfusion, and most of the organisations divided patients into groups according to gestational age and risk factors. As an example, we reported the detailed initiation TSB levels for full-term neonates according to the presence and absence of risk factors in table 7 , finding that there were few differences among the guidelines regarding the initiation of TSB levels. The majority of the guidelines proposed a number of general care strategies during phototherapy, such as temperature measurement, eye protection and continued breastfeeding. Among other forms of phototherapy, home phototherapy was recommended by AAP 13 and MaHTAS, 18 while sunlight exposure was not supported by four organisations (AAP, 13 NICE, 19 QCG, 21 SAP). 22 Moreover, seven guidelines mentioned the complications of phototherapy.

The threshold for initiating exchange transfusion was higher than that for phototherapy in all risk groups. Potential signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy were highlighted as important in all guidelines. Most guidelines reported the details of performing exchange transfusion such as the blood product and blood volume. Double-volume exchange transfusion was advocated by the majority of guidelines. Furthermore, observations during exchange transfusion including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and skin temperature were only proposed by three organisations (MaHTAS, 18 ChPS 15 and ISN). 17 After the exchange transfusion, seven guidelines recommended maintaining intensive phototherapy and six suggested monitoring the TSB at varied time points. Pharmacotherapy was also mentioned by 10 guidelines. However, the recommendation of medication varied greatly.

Most of the guidelines discussed follow-up after discharge, and some provided different follow-up time recommendations according to the time of discharge and risk factors. In addition, some guidelines focused on the follow-up of children with severe hyperbilirubinemia. The CPS 14 guidelines recommend that the hearing screen of patients with severe hyperbilirubinemia should include brainstem auditory evoked potentials. The MaHTAS 18 guideline reported that term and late preterm babies with TSB of >20 mg/dL or exchange transfusions should have auditory brainstem response (ABR) testing performed within the first 3 months of life. If the ABR is abnormal, neurodevelopmental follow-up should be continued. The ABR test was also recommended by the Turkish guidelines for babies with hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment. Moreover, two of the guidelines (SSN 23 and ISN) 17 mentioned the national institute for monitoring the incidence of kernicterus and severe hyperbilirubinemia.

This systematic review appraised 12 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. The quality of the guidelines was highly variable. The included guidelines received acceptable AGREE II scores in the domains of clarity of presentation and scope and purpose, but the mean scores were moderate or low in the stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, applicability and editorial independence domains. This finding was similar to that of the 2010 review by Alonso-Coello et al . 26 In recent years, although the number of guidelines has increased, the quality of guidelines still needs to be improved.

As evaluated by the AGREE II instrument, most guidelines had good clarity regarding their objective, clinical questions and scope. Further, as the AGREE II revealed in the stakeholder involvement domain, many guideline development groups represented a variety of relevant professional areas. 12 It is valuable to explore the views of the target population, that is, healthcare providers or the parents of neonates with hyperbilirubinemia. However, although some guidelines targeted healthcare providers and parents, almost all development groups ignored the preferences of parents of the hyperbilirubinemia neonates.

The mean score of the rigour of development domain, which was considered the indicator of quality in all domains, 27 varied significantly among different guidelines. Guidelines typically received low scores in this domain because of poor reporting of systematic methods for searching for evidence and formulating recommendations, lack of external review and updating mechanisms. Some guidelines, such as NICE, 19 provided detailed search strategies, evidence tables and reasons for excluded studies to confirm their systematic methods, while some guidelines did not provide complete information regarding methods of searching and selecting evidence. Muka et al 28 provided a 24-step guide on how to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2020. The guide described the most important 24 steps, such as defining the search strategy, designing the data collection form, checking reporting bias and so on. We suggest that these methodologically sound tools should be used to help future guideline designers conduct or appraise systematic reviews. Guidelines need to reflect current research, but most of the guidelines did not provide a statement about the procedure for updating. Alonso-Coello et al 29 conducted an international survey of the updating practices of guidelines in 2011 and concluded that there was an urgent need to develop rigorous international standards for the updating process.

The clarity of presentation of the recommendations was specific and unambiguous in most guidelines. The scores of the applicability domain were highly reflective of the implementation of guidelines. Additional materials, including summary documents and educational tools, could be beneficial in this respect. However, >50% of the included guidelines did not discuss facilitators and barriers to their application or tools for practicing; thus, the guidelines might have a limited effect. 30 Therefore, future guideline developers should afford greater consideration to the potential resource implications and facilitators of application, particularly for guidelines published in developing regions. Regarding the editorial independence domain, the views of the funding body and interests of the developers should be reported as part of the standard practice of guideline development.

In this study, we also summarised and compared the specific recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. All guidelines covered the threshold of phototherapy and exchange transfusion, while most of the guidelines stated that the threshold graph was reproduced and adapted with permission from the AAP. 13 However, the AAP noted that the suggested levels represented a consensus of committee but were based on limited evidence, and the levels shown were approximations. 13 Therefore, more qualified studies of different populations are needed to standardise treatment methods. In terms of pharmacotherapy, variations also existed among different guidelines. The discrepancies were mainly due to varying evidence quality, limitations in generalisability and lack of approval by a national administration.

The burden of hyperbilirubinemia is highest in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. 2 Hyperbilirubinemia is the 7th leading cause of neonatal mortality in South Asia, 8th in sub-Saharan Africa, 9th in western Europe and 13th in North America. 2 In our review, we appraised five guidelines from Europe with a mean score of 55.9%, four guidelines from Asian countries with mean scores of 55.2% and two guidelines from North America with mean scores of 50.6%. In 2015, Olusanya et al 31 provided a practical framework for the management of late-preterm and term infants (≥35 weeks of gestation) with clinically significant hyperbilirubinemia in low-income and middle-income countries lacking local practice guidelines. They provided recommendations for comprehensive management, including primary prevention, early detection, diagnosis, monitoring, treatment and follow-up. 31

To our knowledge, our study is the first systematic critical appraisal of guidelines with diagnostic and treatment recommendations targeted to neonates with hyperbilirubinemia. The strengths of our review include the integration of comprehensive search strategies, use of the validated AGREE II instrument and use of four independent reviewers to minimise subjective bias. Further, in addition to guidelines written in English, a Chinese-language guideline by the Chinese Pediatric Society was appraised in our study. As a representative of developing countries, the inclusion of Chinese-language guidelines may minimise the overestimation of the quality of guidelines to some degree.

However, there were several possible limitations to our study. First, guidelines written entirely in languages other than English and Chinese might have been overlooked. Second, the AGREE-II was used to evaluate guidelines with less attention on detailed recommendations. Although it is thought that a global appraisal of a guideline’s developing process may reflect the strength of recommendations, 9 the quality of specific recommendations has a direct influence on practice. Finally, we only assessed guidelines through the reported literature without the use of additional methods such as contacting guideline developers to obtain further clarification. This may have underestimated the systematic methods of guideline development by organisations.

Our study evaluated the quality of methodologies and rigorous strategies in the guideline development process and summarised the recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. The results revealed that current guidelines varied in the quality of the development process and were inconsistent in their recommendations, despite some similarities. Therefore, future guidelines should afford greater attention to the quality of methodologies in the guideline development process, and more qualified evidence is needed to standardise the initiating threshold of treatment for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

- Bhutani VK ,

- Lazzeroni LC , et al

- Olusanya BO ,

- Kassebaum NJ

- Shaneyfelt TM ,

- Mayo-Smith MF ,

- Rothwangl J

- Jolliffe L ,

- Lannin NA ,

- Cadilhac DA , et al

- Johnston A ,

- Hsieh S-C , et al

- Nagler EV ,

- Vanmassenhove J ,

- van der Veer SN , et al

- Kwong JS-W , et al

- Huang T-W ,

- Wu M-Y , et al

- Brouwers MC ,

- Browman GP , et al

- Chapman JR ,

- Wong G , et al

- ↵ Agree II training tools . Available: http://wwwagreetrustorg/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tooles/

- American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia

- ↵ Guidelines for detection, management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in term and late preterm newborn infants (35 or more weeks' gestation) - Summary . Paediatr Child Health 2007 ; 12 : 401 – 7 . doi:10.1093/pch/12.5.401 pmid: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19030400 OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Pediatrics

- Subspecialty Group of Neonatology, The Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association

- Romagnoli C ,

- Pratesi S , et al

- Bratlid D ,

- Nakstad B ,

- Guidelines QC

- Sánchez-Redondo Sánchez-Gabriel MD ,

- Leante Castellanos JL ,

- Benavente Fernández I , et al

- ↵ et al Arlettaz AB R , Buetti, H L , Fahnenstich D . Assessment and treatment of jaundiced newborn infants 35 0/ 7 or more weeks of gestation . Available: https://wwwneonetch/recommendations/authored-ssn 2007

- Türkmen MK ,

- NICE, NIfHaCE

- Alonso-Coello P ,

- Solà I , et al

- Hu Y , et al

- Milic J , et al

- Martínez García L ,

- Carrasco JM , et al

- Sabharwal S ,

- Gauher S , et al

- Ogunlesi TA ,

- Kumar P , et al

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

Correction notice This article has been corrected since it first published. The provenance and peer review statement has been included.

Contributors MZ conceptualised and designed the study, screened the titles and abstracts of searched citations, extracted general characteristics and descriptive data from guideline recommendations, assessed the selected guidelines using the AGREE-II instrument and drafted the initial manuscript. JT conceptualised and designed the study, coordinated and supervised guideline assessment, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. YH screened the titles and abstracts of searched citations, extracted general characteristics and descriptive data from guideline recommendations, assessed the selected guidelines using the AGREE-II instrument and revised the manuscript. WL and ZC assessed the selected guidelines using the AGREE-II instrument, reviewed and revised the manuscript. TX, YQ, YL and DM coordinated and supervised guideline assessment, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Numbers 81630038, 81971433), the grant from Ministry of Education of China (IRT0935), the grant of clinical discipline program (Neonatology) from the Ministry of Health of China (1311200003303) and the grants from the Science and Technology Bureau of Sichuan Province (2020YJ0236, 2020YFS0041).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Topic collections

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 1, Issue 1

- Burden of severe neonatal jaundice: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Tina M Slusher 1 , 2 ,

- Tara G Zamora 1 ,

- Duke Appiah 3 ,

- Judith U Stanke 4 ,

- Mark A Strand 5 ,

- Burton W Lee 6 ,

- Shane B Richardson 7 ,

- Elizabeth M Keating 8 ,

- Ashajoythi M Siddappa 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3826-0583 Bolajoko O Olusanya 9

- 1 Department of Pediatrics , University of Minnesota , Minneapolis , Minnesota , USA

- 2 Hennepin County Medical Center , Minneapolis , Minnesota , USA

- 3 Texas Tech University Health Science Center , Abilene , Texas , USA

- 4 Biomedical Library , University of Minnesota , Minneapolis , Minnesota , USA

- 5 Department of Pharmacy , North Dakota State University , Fargo , North Dakota , USA

- 6 Department of Medicine , University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine , Pittsburgh , Pennsylvania , USA

- 7 Department of Family Medicine , University of Arizona , Tucson , Arizona , USA

- 8 Department of Pediatrics , Baylor College of Medicine , Houston , Texas , USA

- 9 Center for Healthy Start Initiative , Lagos , Nigeria

- Correspondence to Dr Tina M Slusher; tslusher{at}umn.edu

Context To assess the global burden of late and/or poor management of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ), a common problem worldwide, which may result in death or irreversible brain damage with disabilities in survivors. Population-based data establishing the global burden of SNJ has not been previously reported.

Objective Determine the burden of SNJ in all WHO regions, as defined by clinical jaundice associated with clinical outcomes including acute bilirubin encephalopathy/kernicterus and/or exchange transfusion (ET) and/or jaundice-related death.

Data sources PubMed, Scopus and other health databases were searched, without language restrictions, from 1990 to 2017 for studies reporting the incidence of SNJ.

Study selection/data extraction Stratification was performed for WHO regions and results were pooled using random effects model and meta-regression.

Results Of 416 articles including at least one marker of SNJ, only 21 reported estimates from population-based studies, with 76% (16/21) of them conducted in high-income countries. The African region has the highest incidence of SNJ per 10 000 live births at 667.8 (95% CI 603.4 to 738.5), followed by Southeast Asian, Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific, Americas and European regions at 251.3 (132.0 to 473.2), 165.7 (114.6 to 238.9), 9.4 (0.1 to 755.9), 4.4 (1.8 to 10.5) and 3.7 (1.7 to 8.0), respectively. The incidence of ET per 10 000 live births was significantly higher for Africa and Southeast Asian regions at 186.5 (153.2 to 226.8) and 107.1 (102.0 to 112.5) and lower in Eastern Mediterranean (17.8 (5.7 to 54.9)), Americas (0.38 (0.21 to 0.67)), European (0.35 (0.20 to 0.60)) and Western Pacific regions (0.19 (0.12 to 0.31). Only 2 studies provided estimates of clear jaundice-related deaths in infants with significant jaundice [UK (2.8%) and India (30.8%).

Conclusions Limited but compelling evidence demonstrates that SNJ is associated with a significant health burden especially in low-income and middle-income countries.

- neonatology

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000105

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

What is already known on this topic?

Acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE), exchange transfusions and death are frequent and costly outcomes of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) especially in low-income and middle-income countries.

Long-term disabilities including cerebral palsy and deafness can occur following ABE.

The actual burden of SNJ is not well documented.

What this study hopes to add?

A review of population-based literature to assess the global impact of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) highlighting the importance of this disease as defined by its clinical presentations.

Objective evidence that the burden of SNJ is not evenly distributed and that a heavier burden of disease is born by low-income and middle-income countries.

The limited amount of population-based data currently available and the need to capture this information globally.

Introduction

Newborn jaundice occurs in up to 85% of all live births. 1–3 In the absence of haemolysis, sepsis, birth trauma or prematurity, it usually resolves within 3–5 days without significant complications. 1 However, epidemiological evidence suggests that severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) results in substantial morbidity and mortality. 4 SNJ has been recognised as a significant cause of long-term neurocognitive and other sequelae, cerebral palsy, non-syndromic auditory neuropathy, deafness and learning difficulties. 5 6 The burden is unacceptably high in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) and has prompted calls for intense scrutiny and attention. 4 Under the millennium development goals, the potential impact of adverse perinatal conditions such as preterm birth complications and birth asphyxia on thriving and well-being beyond survival rarely received attention. 7 With the current focus on inclusiveness for persons with disability under the sustainable development goals (SDGs), it is essential that we tackle SNJ as one key component of optimising neurodevelopmental outcome. 7 8

A recent report by Bhutani et al 4 noted that at least 481 000 term/near-term neonates are affected by SNJ/hyperbilirubinaemia each year, with 114 000 dying and an additional 63 000 surviving with kernicterus. However, these alarming estimates were based on limited data determined by mathematical modelling as true population-based data are limited and difficult to find. Therefore, the incidence of SNJ and thus its contribution to global neonatal morbidity and mortality presently remain unclear and possibly significantly underestimated.

Jaundice is usually recognised around a total serum bilirubin (TSB) of 5 mg/dL in neonates. 3 SNJ is unlikely to happen before a TSB of at least 20–25 mg/dL in term neonates presenting early. 4 TSB is unfortunately often either not available or delayed in many LMICs. 9 Therefore, for the purposes of this article, severe SNJ is defined as jaundice associated with acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE)/kernicterus and/or exchange transfusions (ET) and/or jaundice-related death.

Phototherapy and ET are widely used therapeutic modalities for jaundice. 2 However, due to constrained resources, devices for measuring bilirubin 10 11 and effective phototherapy are often lacking in LMICs. 12 This, together with higher prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, blood group incompatibilities, late referrals and delayed recognition of excessive bilirubin levels in LMICs, has necessitated excessive use of ETs. 13

We systematically reviewed the available evidence pertaining to the global burden of SNJ to inform child health policy regarding its prevention and management especially in LMICs.

Search criteria

Although most SNJ occurs at TSB at 20 mg/dL (343 µmol/L), there is no standard worldwide definition of SNJ or clinically significant TSB necessitating medical intervention. There is a wide range of definitions of significant jaundice. In studies reviewed in this article, TSB levels considered significant, when results were available, generally ranged from 15 to 30 mg/dL. 14–27 Even though beginning in 2004, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended ABE be used for acute manifestations of SNJ in the first weeks of life and kernicterus for chronic manifestations of SNJ/ABE, 28 many still use the terms interchangeably. Because of limited availability of TSBs and our attempt to quantify the burden of clinical disease, we defined SNJ clinically using ABE, ET and jaundice-related death.

We systematically reviewed published papers following PRISMA guidelines (online supplementary appendix 1 ). 13 Databases searched included Ovid Medline, PubMed, CINAHL, Global Health, Scopus, Popline, Africa Journal Online and Bioline databases for published articles on SNJ. We used both controlled subject headings and free-text terms for neonatal jaundice (NNJ), jaundice, bilirubin/blood levels, haemolytic anaemia, G6PD deficiency in various forms and in combination with terms for ET, ABE, kernicterus, death, mortality and phototherapy. Other inclusion criteria were jaundice in first month of life; availability of data on incidence of ABE/kernicterus; provision of information on incidence of ETs for SNJ or jaundice-related death which we defined as SNJ. We also reviewed references of selected retrieved articles and review papers, and contacted authors of relevant articles for missing dates. No language restrictions were used. To be included in the meta-analysis, a study must have reported estimates of incidence from a retrospective or prospective population-based study, increasing likelihood that estimates could be generalised to the geographical location where the study was conducted. The search results were limited to publication dates of 1990 to June 2017. See online supplementary appendix 2 for complete Ovid Medline search strategy.

Supplementary Material

Data extraction.

Two authors examined studies using a predetermined checklist (online supplementary appendix 3 ) devised by three authors for selecting articles that met inclusion criteria after one author screened titles and abstracts. Two authors independently confirmed eligibility of all full-text articles. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and when needed by a third author. The following data were extracted from each article: publication year, study design, country, WHO region, sample size, SNJ definition and outcomes (ET, ABE, mortality). Articles were excluded if neonates were enrolled before 1990; study published after June 2017; sample size <10; ET unrelated to SNJ, results limited to only metabolic or primary liver diseases, studies with defined enrolment period, failure to define neonates as having ABE, ET or jaundice-related death and for the meta-analysis if they included only premature neonates.

Quality assessment

We explored several quality assessment tools reported in the literature for observational studies including the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, 29 and found none directly applicable for evaluating diagnostic studies on NNJ /hyperbilirubinaemia. We therefore chose to adopt the tool validated by Wong et al 30 with all the critical components for assessing the risk of bias across studies. Two authors examined four important components of quality/risk of bias assessment: selection of subjects (representativeness), case definition for SNJ (exposure ascertainment), diagnostic criteria for jaundice and outcome measurement. Study quality was judged based on number of criteria that were met: all 4 (high), 2–3 (medium) or 1 (low). Finally, two authors determined which studies were population-based. We defined population-based studies as studies that addressed the incidence of SNJ for a defined population with every individual in the population having the same probability of being in the study and the results of the study having the ability to be generalisable to the whole population from which study participants were sampled and not necessarily the individuals included in the study. 31 Disagreements were resolved through consensus after joint reassessment.

Statistical analysis

For the meta-analysis, when multiple reports were obtained from the same population with overlapping study years, the one providing sufficient data (ie, numerator and denominator data) to derive estimates of disease burden was selected. To facilitate meta-analytical techniques, estimates of incidence were logit transformed to enable them to correspond to probabilities under the standard normal and permit use of the normal distribution for significance testing. Pooled estimates were calculated using DerSimonian and Laird’s random effects method, weighting individual study estimates by the inverse of the variance of their transformed proportion as study weight, with their 95% (CI) determined using Clopper-Pearson exact binomial method. 32 For presentation, pooled transformed estimates were back transformed. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was investigated using Cochran’s Q test and I 2 with a conservative p value less than 0.1 chosen as the level of significance. Forest plots were then used to examine the overall effects. Exploration of potential sources of heterogeneity was undertaken using meta-regression. Whether it is an interventional or an observational study, small studies are more likely to show more extreme values given wider CIs compared with larger studies. Since more extreme findings may be more newsworthy and hence more likely to be published, potential for publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot as well as by formal means using Begg’s adjusted rank correlation and Egger’s regression asymmetry tests. 33 All analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software. 34

Search of electronic databases identified 6844 articles ( figure 1 ). Eight hundred and twenty papers were reviewed. After excluding studies not meeting inclusion criteria, 416 studies were selected for further review. Multiple languages (Chinese, English, Farsi, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Serbian and Spanish) were represented, with translation of relevant sections, but only 26/416 were non-English, none of which were population based. Of these, 416 papers included at least one marker of SNJ, but only 21 provided population-based data on 4 975 406 neonates ( table 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Flow chart of study selection for the meta‐analysis.

- View inline

Studies that met the inclusion criteria to be included in the meta-analysis

Sixteen (76%) were from high-income countries and 13 (62%) used a prospective study design. High-quality studies tended to report lower incidence compared with low-quality to moderate-quality studies ( figure 2 ). High-quality studies tended to come from high-income countries with less disease while low-quality studies tend to come from LMICs. Overall, incidence estimates of SNJ from high-income countries tended to be lower compared with LMICs ( figure 3 ). Studies which enrolled all neonates regardless of gestational age had a higher incidence of SNJ compared with studies enrolling only term/near-term ( table 2 ).

Pooled incidence (per 10 000) of severe neonatal jaundice among all neonates aged 24 months or less according to study quality.

Pooled incidence (per 10 000) of severe neonatal jaundice among all neonates aged 24 months or less according to income.

Incidence (per 10 000 live births) of severe neonatal jaundice among all neonates aged 24 months or less by gestation and study design

The incidence of SNJ per 10 000 live births was highest in the African region at 667.8, followed by Southeast Asian at 251.3, Eastern Mediterranean with 165.7 and Western Pacific region with 9.4. The Americas and European regions each had substantially lower incidence of 4.4 and 3.2, respectively ( table 3 ).

Incidence of severe neonatal jaundice per 10 000 live births, among all neonates aged 24 months or less

The incidence of ET per 10 000 live births was significantly higher for the African (186.5) and Southeast Asian (107.1) regions and lower in Eastern Mediterranean, Americas, European and Western Pacific regions reporting estimates of 17.8, 0.38, 0.35 and 0.19, respectively ( table 4 ).

Incidence of exchange transfusions, per 10 000 live births, among all neonates aged 24 months or less

Visual inspection of funnel plot in which incidences of SNJ were plotted against their standard errors showed asymmetry. This was confirmed by formal tests of publication bias (Begg-Mazumdar test: p=0.016, Egger: bias, p=0.002). The observed heterogeneity between studies may explain the asymmetric funnel plots. In random effects meta-regression analyses, the overall observed between-study heterogeneity explained by covariates which were selected a priori (study design and duration, income classification of country and gestational age) was 66.23%; p<0.001. However, only income classification of country was statistically significant determinant of the incidence of SNJ ( table 5 ). Only two studies provided information on jaundice-related deaths with estimates of 2.8, 30.8 and 50.0 for UK (European), 22 and India (Southeastern) 35 While one study fromPakistan 3 (Eastern Mediterranean), mentions death in 30% of infants with jaundice but stated they did not feel the deaths could be directly attributed to jaundice.

Meta-regression analysis potential factors* influencing the heterogeneity of incidence of severe neonatal jaundice

Although data are limited despite our extensive literature review, this systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that the incidence of SNJ is high, with regions that include predominantly LMICs bearing the greatest burden of disease. In the systematic review, mentioned earlier by Bhutani et al 4 18% of 134 million live births had SNJ with the greatest burden of disease in LMICs, and therefore supporting this hypothesis. But as previously pointed out, these estimates were generated by mathematical modelling due to lack of accurate incidence data available. Both Bhutani’s data as well as this review, highlight the glaring paucity of studies particularly in LMICs. Although all WHO regions are represented, only 4/136 (2.9%) LMICs countries were represented with most having only one study (India (Southeast) n=2, 25 35 Nigeria (African) n=1 36 and Pakistan (Eastern Mediterranean) n=1, 3 Vietnam (Western Pacific) n=1). 37 In contrast representation among high-income countries, while low was better with 8/79 (10.1%) high-income countries having population-based data (Australia (Western Pacific) n=1, 23 Canada (Americas) n=3, 26 38 Denmark (European) n=3, 15 17 39 Norway (European) n=1, 24 Netherlands (European) n=1, 20 Switzerland (European) n=1, 27 USA (Americas) n=5, 16 18 19 40 UK and Ireland (European) n=1). 22 This general lack of population-based studies worldwide emphasises the need for more accurate data to determine the actual burden of disease.

Jaundice was the primary diagnosis in 17% of neonates ≤1 week in a hospital-based study in Kenya, 41 and several other African-based studies demonstrate that SNJ commonly leads to hospital admissions. 42–44 This pattern is also observed in Asia, including the Middle East. 41 45–49

Although not readily generalisable, all regions do have numerous hospital-based studies among the 416 articles with at least one clinical indicator of SNJ, highlighting the prevalence of SNJ among admissions. For some countries, such as the USA and many European nations where hospital birth is the norm, this data would more accurately reflect true population-based data. However, in LMICs where ‘60 million women give birth outside a facility’ (2012) 50 and recorded data population data spares, hospital data cannot be assumed to reflect true population data. The higher incidence of home births correlates well with the much higher incidence of SNJ noted in the studies from the African, Southeast Asian and Eastern Mediterranean regions compared with substantially lower incidence noted in the regions of the Americas and Europe.

Although only one study each from Africa and Eastern Mediterranean met the definition of population based, these two studies underscore the burden of ETs in LMIC’s with 186.5 and 107.1 ET’s per 10 000 live births in stark contrast to the American and European regions with only 0.38 and 0.35 per 10 000 live births, respectively.

While many paediatricians and even neonatologists in high-income countries never perform an ET, physicians in LMICs continue to perform ETs on a regular basis. 13 Although population-based data were available in only a few LMICs studies, other hospital-based studies support their findings. Of note again is the high prevalence of ETs, reported in studies from many LMIC (22%–86%), particularly Nigeria, 36 51 52 India 53 54 and Bolivia. 55

Access to ET, a proxy indicator of the magnitude of SNJ, is often limited in resource poor countries. 13 56 57 Multiple studies have demonstrated early intervention including phototherapy and appropriate ET can prevent kernicterus. 56 58 59 Despite benefits of ET, there are associated complications 13 making it important to provide effective phototherapy before ET is needed. 60

SNJ is significant due to the associated mortality, but some would argue even more so because of associated long-term morbidity especially in LMICs ill-equipped to handle these disabilities. Farouk et al reported abnormal neurological findings in almost 90% of infants returning for follow-up after ABE in their nursery. 61 Olusanya and Somefun, 62 reported ET as a risk factor for sensorineural hearing loss in their community-based study in Nigeria, as did da Silva et al in Brazil. 63

Contribution of SNJ to neonatal mortality

While only two studies in this review, 22 35 64 provided information on clear jaundice-related deaths, other studies have shown striking numbers of jaundice-related deaths where it reportedly accounted for 34% of neonatal deaths in Port Harcourt Nigeria, 52 15% in Ile-Ife, Nigeria, 65 14% in Kilifi District Kenya, 66 6.7% in Cairo Egypt 67 and 5.5% in Lagos Nigeria. 68

Multiple factors contributing to kernicterus in LMICs and the need for solutions addressing these factors has been spelled out in articles by Olusanya et al 69 and Slusher et al 2 including the need for national guidelines, 9 60 effective phototherapy, rapid reliable diagnostic tools, maternal and healthcare provider education. 70

Contribution of SNJ to long-term disability

Current evidence indicates SNJ continues to contribute significantly to the burden of cerebral palsy, deafness and other auditory processing disorders. 4 In India, Mukhopadhyay et al 71 found an abnormal MRI or brainstem auditory evoked response in 61% and 76%, respectively, of children who underwent ET. In Nigeria, Ayanniyi and Abdulsalam 72 reported NNJ as the leading cause of cerebral palsy (39.9%) trumping birth asphyxia (26.8%), while Ogunlesi et al 73 also from Nigeria, reported cerebral palsy, seizure disorders and deafness as leading sequelae of ABE, occurring in 86.4%, 40.9% and 36.4%, respectively. Oztürk et al from Turkey, 74 observed a history of prolonged jaundice commonly in children affected with cerebral palsy. Summing up available estimates, a recent Lancet article by Lawn et al 75 indicts pathological hyperbilirubinaemia/jaundice in >114 000 deaths and states that there are >63 000 damaged survivors.

The increased global awareness of SNJ has led to improvement in some locations. One notable example of this is Myanmar where a package of services including a photoradiometer, education and intensive phototherapy decreased ET by 69%. 76 Another example is the development, ongoing testing and refinement of filtered sunlight phototherapy in areas without access to continuous electricity or intensive phototherapy. 77 Several studies have shown that maternal and health worker education, screening programmes 14 18 28 38 and national guidelines 78 can and do improve outcomes and decrease the observed clinical sequelae of SNJ. 14 38 78 Many programmes supported by groups such as WHO 79 and Essential Care for Every Baby 80 now strongly support screening for jaundice and highlight it as a danger sign needing urgent care. This increased focus and awareness on SNJ is beginning to lead to decreases of this problem even in LMICs where recent studies though not always population based are beginning to show decreases in severe sequela. 76

Some limitations of this comprehensive review should be noted, besides those inherent in meta-analysis. 81 Only 12/195 sovereign nations 82 are represented in the quantitative data. While highlighting one of the greatest problems in determining the actual burden of disease from SNJ, absence of data from other countries despite searching multiple databases limits generalisability of our findings. Another significant limitation is the marked variability in the actual focus of the articles. The populations studied, availability of a TSB, recommendations and methods of screening, differences in TSBs and many other variables of included articles span an extremely wide range. Finally, the initial search excluding articles by title was done by only one author and the auditory evoked brainstem response, which is rarely available in LMICs, where not included in the criteria for SNJ.

Despite these limitations, this review still fills critical holes in our knowledge about the true burden of disease from this devastating but preventable tragedy. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to report the global burden of SNJ derived from population-based studies. While providing strong evidence for the burden of disease, it highlights the notable lack of population-based data from most countries, especially LMICs where the disease is more prevalent and most devastating. The burden of SNJ and its acute and chronic ramifications establish a strong case for appropriate health education, routine screening, early diagnosis and effective treatment. The spectrum of disease crosses ethnic and socioeconomic boundaries, impacting children everywhere, and is a commonly encountered hospital diagnosis worldwide. SNJ may represent the most common unrecognised and/or under-reported neonatal cause of preventable brain damage. 83 More research with capacity building especially in LMICs and other areas where data are limited are needed to truly quantify the impact of this disease and to better understand how to integrate screening and therapy to eliminate this disease in the future.

Compelling but limited evidence from the literature demonstrates that SNJ is associated with a significant acute and chronic health burden, especially in LMICs. There is an urgent need to address this preventable disease in these regions, consistent with the inclusiveness advocated for erstwhile disadvantaged populations under the current SDGs dispensation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Vinod Bhutani, Ms. Judith Hall RNC-NIC, and Dr Mark Ralston for their edits to an earlier version of the manuscript. We also thank Dr Philip Fischer, MD, Dr Reza Khodaverdian, Dr Janielle Nordell, Ms Ann Olthoff, RN, Dr Clydette Powell, Dr Hoda Pourhassan, Dr Maryam Sharifi-Sanjani, Ms Olja Šušilović, Dr Deborah Walker, Ms Allia Vaez and Ms Agnieszka Villanti, RN, for their help in the translation of foreign language literature used in this review. We also thank Ms Ayo Bode-Thomas, Dr Katie Durrwachter Erno, Mr Jeffrey Flores, Ms Judith Hall, RNC-NIC, Mr Jonathan Koffel, Ms Toni Okuyemi, Dr Mark Ralston, Mr Del Reed, Mr Paul Reid, Dr Yvonne Vaucher, Ms Mabel Wafula, Ms Katherine Warner, Dr Olga Steffens for their help in editing the article/tables including retrieving articles, verifying numbers, and managing Endnote.

- 1. ↵ National Institutes for Health and Clinical Excellence . Neonatal jaundice. (clinical guidelines 98 ) , 2010 .

- Slusher TM ,

- Zipursky A ,

- Tikmani SS ,

- Warraich HJ ,

- Abbasi F , et al

- Bhutani VK ,

- Blencowe H , et al

- Mwaniki MK ,

- Lawn JE , et al

- Blencowe H ,

- Darmstadt GL , et al

- Njelesani J

- Olusanya BO ,

- Ogunlesi TA ,

- Donaldson KM , et al

- Mabogunje CA ,

- Olaifa SM ,

- Olusanya BO

- Knauer Y , et al

- Bjerre JV ,

- Petersen JR ,

- Christensen RD ,

- Lambert DK ,

- Henry E , et al

- Ebbesen F ,

- Andersson C ,

- Verder H , et al

- Eggert LD ,

- Wiedmeier SE ,

- Wilson J , et al

- Flaherman VJ ,

- Kuzniewicz MW ,

- Escobar GJ , et al

- Gotink MJ ,

- Benders MJ ,

- Lavrijsen SW , et al

- Escobar GJ ,

- Wi S , et al

- Manning D ,

- Maxwell M , et al

- McGillivray A ,

- Polverino J ,

- Badawi N , et al

- Johansen KB

- 25. ↵ National neonatal perinatal database . National neonatal perinatal database: report: 2002-2003 . New Delhi : Nodal Centre , 2005 .

- Campbell D ,

- Berrut S , et al

- 28. ↵ American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation . Pediatrics 2004 ; 114 : 297 – 316 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- Sanderson S ,

- Cheung CS ,

- DerSimonian R ,

- Davey Smith G ,

- Schneider M , et al

- 34. ↵ R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program] . Vienna, Austria : R Foundation for Statistical Computing , 2013 .

- Baitule S , et al

- Akande AA ,

- Emokpae A , et al

- Partridge JC ,

- Tran BH , et al

- Parmar SM ,

- Allegro D , et al

- Vandborg PK

- Wickremasinghe AC ,

- Wu YW , et al

- Iroha E , et al

- Mukhtar-Yola M ,

- 45. ↵ Subspecialty Group of Neonatology . Epidemiologic survey for hospitalized neonates in China . China J Contemp Pediatr 2009 ; 11 : 15 – 20 . OpenUrl

- Taşçilar E , et al

- Partridge J ,

- Chaudhary D ,

- Adhikary V , et al

- Abd El-Latif M ,

- Abd El-Latif D

- 50. ↵ Newborn Health: The Issue . http://www.savethechildren.org/ accessed 13 Dec 2016 , 2016

- Oruamabo RS

- Gathwala G ,

- 54. ↵ National Neonatal Perinatal Database . Morbidity and mortality among outborn neonates at 10 tertiary care institutions in India during the year 2000 . J Trop Pediatr 2004 ; 50 : 170 – 4 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Ogunlesi TA

- Ogunfowora OB

- Agrawal VK ,

- Misra PK , et al

- Johnson L ,

- Kumar P , et al

- Farouk ZL ,

- Muhammed A ,

- Gambo S , et al

- da Silva LP ,

- Queiros F ,

- Adeolu AA ,

- Arowolo OA ,

- Alatise OI , et al

- Gatakaa HW ,

- Mturi FN , et al

- Iskander I ,

- Gamaleldin R ,

- El Houchi S , et al

- Emokpae AA ,

- Imam ZO , et al

- Zamora TG , et al

- Mukhopadhyay K ,

- Chowdhary G ,

- Singh P , et al

- Ayanniyi O ,

- Abdulsalam KS

- Dedeke IO ,

- Adekanmbi AF , et al

- Demirci F ,

- Yavuz T , et al

- Oza S , et al

- Arnolda G ,

- Trevisanuto D , et al

- Vreman HJ , et al

- Kandasamy S ,

- Shah V , et al

- 79. ↵ World Health Organization . Newborn: reducing mortality , 2014 . http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs333/en/ ( accessed 15 Aug 2017 ).

- 80. ↵ Essential Care for Every Baby - AAP.org . 2017 https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy.babies./Essential-Care-Every-Baby.aspx (accessed 2 Sep 2017) .

- Greenland S

- 82. ↵ Independent States of the World . http://www.nationsonline.org/

Contributors TS and BOO conceptualised and designed the study, acquired data, analysed and interpreted data, supervised the study, drafted the manuscript and conducted a critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the manuscript as submitted. TGZ conceptualised and designed the study, and assisted with acquiring data and approved the manuscript as submitted. AMS assisted in acquiring data and approved the manuscript as submitted. EMK and JUS were responsible for acquisition of data as well as providing administrative, technical and material support and approved the manuscript as submitted. SBR was responsible for acquisition of data, analysing and interpreting data and provided administrative, technical and material support and approved the manuscript as submitted. DA, MAS and BWL analysed and interpreted the data, conducted the statistical analysis, and conducted a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript as submitted. All authors had full access to all data, take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the data and approved the manuscript as submitted.

Funding Support for the quantitative analysis was provided in part by The Programme for Global Paediatric ReSouth-East Asianrch, Centre for Global Child Health, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Published: 01 February 2021

Neonatal jaundice and autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Monica L. Kujabi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2901-3417 1 ,

- Jesper P. Petersen 2 ,

- Mette V. Pedersen 2 ,

- Erik T. Parner 3 &

- Tine B. Henriksen 2

Pediatric Research volume 90 , pages 934–949 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2489 Accesses

9 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Two meta-analyses concluded that jaundice was associated with an increased risk of autism. We hypothesize that these findings were due to methodological limitations of the studies included. Neonatal jaundice affects many infants and risks of later morbidity may prompt physicians towards more aggressive treatment.

To conduct a systematic literature review and a meta-analysis of the association between neonatal jaundice and autism with particular attention given to low risk of bias studies . Pubmed, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane, and Google Scholar were searched for publications until February 2019. Data was extracted by use of pre-piloted structured sheets. Low risk of bias studies were identified through predefined criteria.

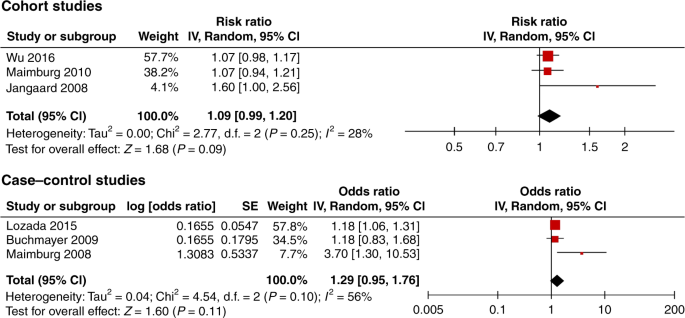

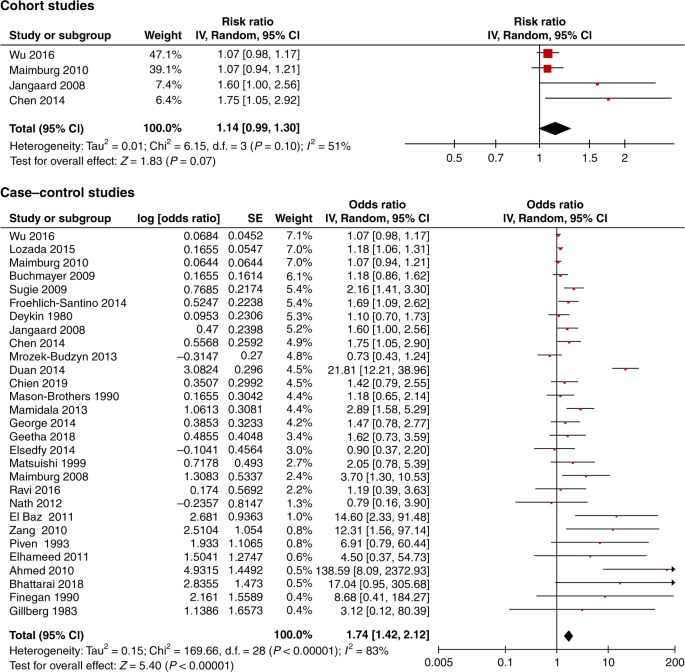

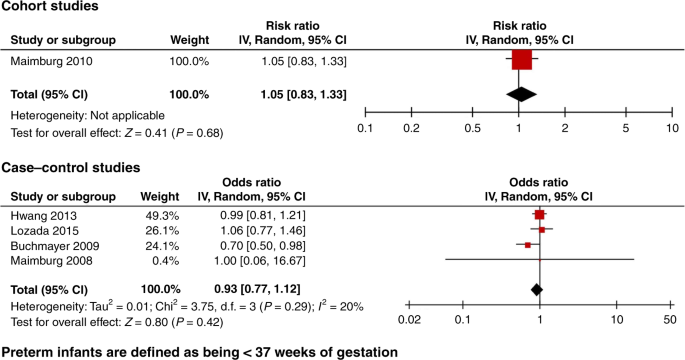

A total of 32 studies met the inclusion criteria. The meta-analysis of six low risk of bias studies showed no association between neonatal jaundice and autism; cohort studies risk ratio 1.09, 95% CI, 0.99–1.20, case-control studies odds ratio 1.29 95% CI 0.95, 1.76. Funnel plot of all studies suggested a high risk of publication bias.

Conclusions

We found a high risk of publication bias, selection bias, and potential confounding in all studies. Based on the low risk of bias studies there was no convincing evidence to support an association between neonatal jaundice and autism.

Meta-analysis of data from six low risk of bias studies indicated no association between neonatal jaundice and autism spectrum disorder.

Previous studies show inconsistent results, which may be explained by unadjusted confounding and selection bias.

Funnel plot suggested high risk of publication bias when including all studies.

There is no evidence to suggest jaundice should be treated more aggressively to prevent autism.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Consensus definition and diagnostic criteria for neonatal encephalopathy—study protocol for a real-time modified delphi study

Postnatal steroid therapy is associated with autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents of very low birth weight infants

Italian neonatologists and SARS-CoV-2: lessons learned to face coming new waves

Introduction.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a disease defined by symptoms in the following three domains; social interaction, communicative disorders, and stereotyped, repetitive or restricted behavior. 1 This review focuses on ASD, including all subtypes. The prevalence of ASD is 1−2%, and has increased since the 1940s. 2 , 3 , 4 ASD is more than four times as prevalent in boys than in girls. 2 The etiology of ASD is unknown, but studies indicate involvement of both genetic 5 , 6 , 7 and non-inheritable factors. 8 , 9 ASD is a disease with long-term consequences for both the child and the family. 10 Accordingly, there is a need to identify preventable causes of ASD. Neonatal jaundice occurs in some 80% of neonates. 11 Unconjungated bilirubin crosses the blood−brain barrier in the newborn and high levels may cause acute bilirubin-induced encephalopathy and permanent brain damage. 12 The most common neuropathological findings in children with ASD are a decreased number of purkinje cells in the cerebellum, decreased neuronal cell size, and increased cell packing density in the cerebral cortex. 13 , 14 These areas may also be damaged by bilirubin deposition in brain tissue. 12 , 15 , 16 Accordingly, an association between hyperbilirubinemia and ASD seems plausible. 17 Reviews by Amin et al. 16 and Jenabi et al. 18 concluded that neonatal jaundice was associated with an increased risk of ASD. In the review by Amin et al. no structured quality assessment was performed and the conclusion was based on a meta-analysis of all studies regardless of their quality. Jenabi et al. rated 19 out of 21 studies as high quality despite methodological limitations of some studies including no adjustment for confounders. The purpose of this systematic review was to compile and critically review the existing evidence of the association between jaundice and ASD and to base the conclusion only on studies with low risk of bias .

Search strategy

This study is conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guideline (see PRISMA checklist). A systematic literature search was carried out according to the review protocol published in PROSPERO, protocol number: CRD42016025927. Pubmed, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane, and Google Scholar were searched for publications until February 2019. The search terms included autism, autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder (PDD), ASD, Asperger, hyperbilirubinemia, jaundice, icterus, bilirubin, newborn/perinatal/neonatal risk factor (s), phototherapy. MESH terms were used whenever available. The full search strategy can be found in Supplementary Text S1 (online). References of included studies and other relevant reviews were screened to identify additional studies.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All case−control and cohort studies examining the association between jaundice, hyperbilirubinemia, or phototherapy and ASD, that provided absolute numbers were eligible.

Exposure measures had to be either neonatal hyperbilirubinemia or jaundice based on clinical assessment, parental report, laboratory confirmation by estimating serum bilirubin during the neonatal period (within 28 days after birth), or phototherapy treatment.

The outcome measure was ASD, which include childhood/infantile autism, autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified, and Asperger’s. In the literature the terms autism, ASD, and PDD are often used interchangeably; thus, all were included.

To be able to tease out the details of each study, only studies in English peer-reviewed journals were included. Conference abstracts and studies without a reference group such as case series or case reports were excluded.

Studies that adjusted for confounding factors, but did not include the adjusted results, were excluded from the meta-analysis. Studies that investigated preterm infants only were included in a sub-analysis of preterm infants.

Study selection and data extraction

Titles and abstracts of all identified records were screened for eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If immediate exclusion based on title and abstract was not possible, the full text was assessed for eligibility. Structured sheets piloted prior to the search were used for data extraction from each study (see Table 1 ).

Low risk of bias studies

Studies passed the threshold for strong methodological quality, if they met the following criteria: ASD diagnosis based on International Classification of Diseases/Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (ICD/DSM), jaundice was based on TSB measurement or jaundice diagnosis from medical records, and adjustment for at least sex 2 and either gestational age (e.g. term vs. preterm or gestational week at birth) or birth weight. 19 These quality criteria were defined after the development of the PROSPERO protocol, but prior to data extraction. Studies that met the quality criteria were defined as low risk of bias studies . Only low risk of bias studies were subjected to further quality assessment.

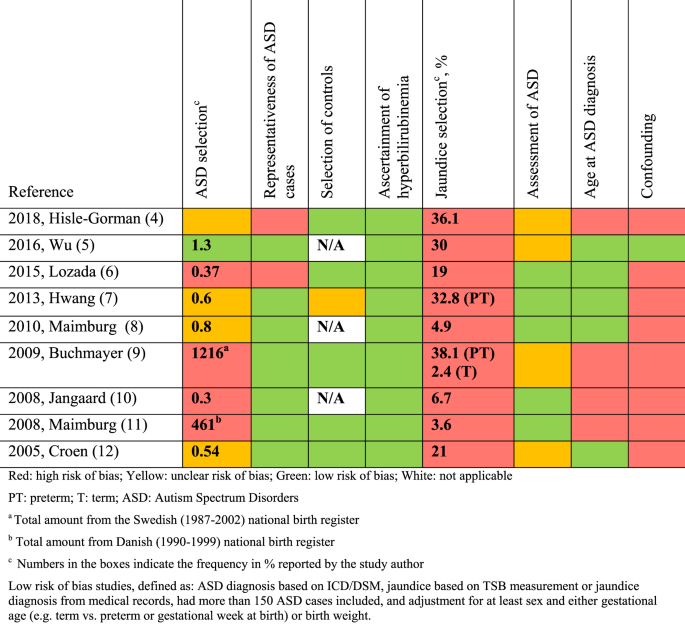

Quality assessment

The quality-assessment was guided by the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, 20 the STROBE checklist 21 (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology), and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. 22 We defined essential confounders as: sex, 2 gestational age 19 or birth weight, 19 birth year, 4 and Apgar score. 19 According to current evidence, these may likely influence the association and should be adjusted for. 23 Other potential confounding factors such as pregnancy complications, parental age, education, and socioeconomic status were also considered, but not deemed essential due to the paucity of studies between these variables and ASD. To further evaluate the quality of the low risk of bias studies , the risk of bias in predefined areas (ASD selection, representativeness of ASD cases, selection of controls, ascertainment of hyperbilirubinemia, jaundice selection, assessment of ASD, age at ASD assessment, confounding) were rated as low, high or unclear risk of bias (Fig. 1 ). This assessment aimed to show the quality of the studies without suggesting how that might influence the effect estimates. The quality-assessment was based on a risk of bias table (Supplementary Table S2 (online)) and assessment of confounders (Supplementary Table S3 (online)) made a priori by the authors.

Qualitative assessment of low risk of bias studies based on predefined criteria (Supplementary Table S2 ).

Literature search, inclusion, data extraction, selection of low risk of bias studies , and quality assessment of low risk of bias studies were conducted independently by two authors (M.L.K. and M.V.P.). In case of discrepancy between the two authors, a third author (T.B.H.) was conferred.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager Software (RevMan version 5.3). 24 Adjusted effect measures were used when available. The unadjusted risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) was calculated from absolute numbers with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) if adjusted estimates were unavailable. Effect measures were entered into RevMan using the “generic inverse variance” outcome. OR and RR were analyzed separately in the meta-analysis because case−control and cohort studies are heterogenic and may have different challenges related to methodology. A random-effects model was used to analyze the included studies as a random sample of a hypothetical population of studies. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using I 2 , which describes the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. 25 , 26 A forest plot and meta-analyses using a logarithmic scale were made for all studies, the low risk of bias studies , and for preterm infants. A funnel plot was used to assess selective reporting.

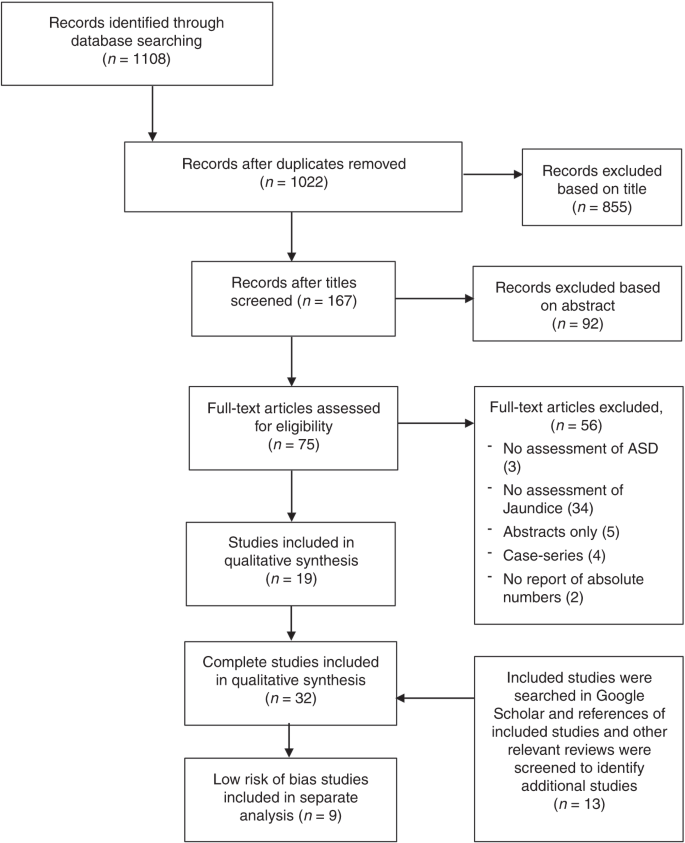

Literature search

Literature search was conducted in February 2019 (PRISMA flow chart in Fig. 2 ) identifying a total of 32 studies to be included in this review. Two studies by Maimburg et al. 27 , 28 were both included, despite overlapping by 5 years. However, they also represent 10 years without overlap.

PRISMA flow chart for the systematic review detailing the number of abstracts and full-text screened and number of studies excluded.

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the main characteristics and effect estimates from all 32 included studies. The earliest study dates back to 1979. The total number of children with ASD across all studies was 29,299. Differences in the definition of jaundice (parental assessment by self-administered questionnaires, clinical diagnosis, diagnosis by TSB levels, the need for treatment by phototherapy) and the definition of ASD (diagnosis by ICD-8, 9 or 10 or DSM-III, IV or V) compromised overall comparability.

Nine studies met the low risk of bias criteria. The low risk of bias studies included 24,440 children with ASD. The studies that were not included in the low risk of bias studies failed to adjust for any potential confounding factors or they based the information on jaundice on parental recall. Fig. 1 shows the quality assessment of each of these nine studies and Supplementary Table S3 (online) shows the potential confounders adjusted for. As seen in Fig. 1 even the studies we considered low risk of bias studies had several limitations. Of the nine studies two reported an increased risk of ASD with jaundice, 28 , 29 the seven remaining studies showed no association between jaundice and ASD. 27 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 These nine studies were thoroughly reviewed and their main characteristics are summarized in the following narrative syntheses ordered according to their weight in the meta-analyses, with cohort studies first.

Narrative description of low risk of bias studies

Wu et al. 31 based their cohort study on 457,855 children born 1995–2011 at 15 Kaiser Permanente Northern California hospitals (KPNC) covering 40% of the insured population. They found no association between jaundice and ASD (RR 1.07, 95% CI, 0.98–1.17). Neonatal jaundice was found in 30% and ASD in 1.3% of the included population. Jaundice was defined as TSB > 10 mg/dL, and 51% of all newborns in the study had TSB measured. ASD was defined according to ICD-9 and retrieved from the KPNC registry. Children were either diagnosed at autism evaluation centres, by a clinical specialist outside the ASD center, or by a general pediatrician. The study adjusted for all our predefined essential confounders. They estimated the effect of phototherapy, and found that use of phototherapy did not change the association between jaundice and ASD.