Postpartum depression: Causes, symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options

- Women and Girls

What is postpartum depression and anxiety?

It’s common for women to experience the “baby blues”—feeling stressed, sad, anxious, lonely, tired or weepy—following their baby’s birth. But some women, up to 1 in 7, experience a much more serious mood disorder—postpartum depression (PPD). (Postpartum psychosis, a condition that may involve psychotic symptoms like delusions or hallucinations, is a different disorder and is very rare.) Unlike the baby blues, PPD doesn’t go away on its own. It can appear days or even months after delivering a baby; it can last for many weeks or months if left untreated. PPD can make it hard for you to get through the day, and it can affect your ability to take care of your baby, or yourself. PPD can affect any woman—those with easy pregnancies or problem pregnancies, first-time mothers and mothers with one or more children, women who are married and women who are not, and regardless of income, age, race or ethnicity, culture, or education.

What are the symptoms of PPD?

The warning signs are different for everyone but may include:

A loss of pleasure or interest in things you used to enjoy, including sex

Eating much more, or much less, than you usually do

Anxiety—all or most of the time—or panic attacks

Racing, scary thoughts

Feeling guilty or worthless; blaming yourself

Excessive irritability, anger, or agitation; mood swings

Sadness, crying uncontrollably for very long periods of time

Fear of not being a good mother

Fear of being left alone with the baby

Inability to sleep, sleeping too much, difficulty falling or staying asleep

Disinterest in the baby, family, and friends

Difficulty concentrating, remembering details, or making decisions

Thoughts of hurting yourself or the baby (see below for numbers to call to get immediate help).

If these warning signs or symptoms last longer than 2 weeks, you may need to get help. Whether your symptoms are mild or severe, recovery is possible with proper treatment.

What are the risk factors for PPD?

A change in hormone levels after childbirth

Previous experience of depression or anxiety

Family history of depression or mental illness

Stress involved in caring for a newborn and managing new life changes

Having a challenging baby who cries more than usual, is hard to comfort, or whose sleep and hunger needs are irregular and hard to predict

Having a baby with special needs (premature birth, medical complications, illness)

First-time motherhood, very young motherhood, or older motherhood

Other emotional stressors, such as the death of a loved one or family problems

Financial or employment problems

Isolation and lack of social support

What can I do?

Don’t face PPD alone. To find a psychologist or other licensed mental health provider near you, ask your OB/GYN, pediatrician, midwife, internist, or other primary health care provider for a referral. APA can also help you find a local psychologist: Call 1-800-964-2000, or visit the APA Psychologist Locator .

Talk openly about your feelings with your partner, other mothers, friends, and relatives.

Join a support group for mothers—ask your health care provider for suggestions if you can’t find one.

Find a relative or close friend who can help you take care of the baby.

Get as much sleep or rest as you can even if you have to ask for more help with the baby—if you can’t rest even when you want to, tell your primary health care provider.

As soon as your doctor or other primary health care provider says it’s okay, take walks, or participate in another form of exercise.

Try not to worry about unimportant tasks. Be realistic about what you can do while taking care of a new baby.

Cut down on less important responsibilities.

Remember that postpartum depression is not your fault—it is a real, but treatable, psychological disorder. If you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or your baby, take action now: Put the baby in a safe place, like a crib. Call a friend or family member for help if you need to. Then, call a suicide hotline (free and staffed all day, every day):

IMAlive 1-800-SUICIDE (1-800-784-2433)

988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline Dial 988 (Formerly known as The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK)

Other versions

Download this Brochure (PDF, 476KB)

En Español (PDF, 419KB)

En Français (PDF, 240KB)

中文 (PDF, 513KB)

All translations of the English Postpartum Depression brochure were partially funded by a grant from the American Psychological Foundation.

Crisis hotlines and resources

Postpartum Health Alliance

Postpartum Support International

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

Health Resources and Services Administration

National Women’s Health Center

- Psychology topics: Women and girls

- Psychology topics: Depression

You may also like

Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Postpartum depression.

Although for many people the birth of a child is an exciting part of life, for some it may cause adverse health outcomes. One of them is postpartum depression that can be characterized by mood swings, sleep deprivation, and anxiety. This paper discusses a patient that presented in the clinic with these symptoms. It outlines the possible treatment and therapy methods, as well as the implications of the condition.

A 28-year-old patient presented in the office three weeks after giving birth to her first son with the symptoms of postpartum depression. The woman was a single mother; she did not have a strong support system as her former partner refused to help her and her family lived in a different state. She noted that she was sleep-deprived, she felt apathetic, sad, experienced anxiety, and had a decreased appetite.

The patient reported that she was diagnosed with depression seven years ago but underwent treatment and had not had the symptoms for a long time. The woman noted that her mother also had signs of a mental disorder but never sought professional help. The patient cried while talking to me; her emotional state was poor. In addition, the woman admitted that she had thought of harming her newborn son because she felt that she was tired of taking care of him.

The typical signs of postpartum depression include the presence of sleep disorder, fatigue, crying, anxiety, changes in appetite, and feelings of inadequacy (Tharpe, Farley, & Jordan, 2017). The patient has these symptoms, which allowed for establishing the diagnosis. Drug therapy included the prescription of tricyclic antidepressants, as they do not pose risks to infants during breastfeeding (Anxiety and Depression Association of America, 2018). Additional therapies included adequate nutrition with the exclusion of caffeine and herbal remedies, such as 2 cups of lemon balm tea daily (Tharpe et al., 2017).

Moreover, I advised the woman to participate in support groups’ meetings and have a scheduled time for personal care, hobbies, and favorite activities, as well as sleep. In addition, I asked the patient to try to have some time away from her child as it could improve her mental state as well. As for follow-up care measures, I suggested that the woman could document her thoughts and feelings and update me on the changes in her condition by visiting my office in two weeks. Moreover, I invited the patient to participate in an educational session on the aspects of postpartum depression.

The primary implication of the woman’s condition is that it is vital to educate individuals on its symptoms and assure them that this experience is common. Moreover, it is necessary to continue establishing support groups and psychotherapy sessions aimed to eliminate this issue. Postpartum depression may affect not only this woman but her entire family unit as the individuals close to the patient can also start experiencing emotional distress and other related symptoms. In the case of my patient, the condition may affect her relationships with her child, potentially causing a poor emotional bond and behavioral problems in the infant.

Postpartum depression is a severe condition that may affect a patient’s life significantly. It can cause individuals to feel anxious, experience mood swings and changes in appetite, and have thoughts of harming their newborn children. The management strategy for this illness can include drug therapy along with alternative remedies. It is vital to establish support groups and educational training for people having postpartum depression to decrease its incidence.

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2018). Postpartum depression . Web.

Tharpe, N. L., Farley, C., & Jordan, R. G. (2017). Clinical practice guidelines for midwifery & women’s health (5th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

- Dame Stephanie Shirley's Psychological Adjustments

- Dimensions of Psychology and Its Specialty Areas

- Postpartum Depression and Acute Depressive Symptoms

- Supporting the Health Needs of Patients With Parkinson’s, Preeclampsia, and Postpartum Depression

- Technology to Fight Postpartum Depression in African American Women

- Anxiety Disorder: Psychological Studies Comparison

- Mental Illness With Mass Shootings

- A Review of Postpartum Depression and Continued Post Birth Support

- Role of Behavioral Science in Treatment of Dyslexia and Dyscalculia

- The Psychological and Social Problems in Students

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 9). Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy. https://ivypanda.com/essays/postpartum-depression-discussion/

"Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy." IvyPanda , 9 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/postpartum-depression-discussion/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy'. 9 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy." July 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/postpartum-depression-discussion/.

1. IvyPanda . "Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy." July 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/postpartum-depression-discussion/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Postpartum Depression: Treatment and Therapy." July 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/postpartum-depression-discussion/.

Academic Support for Nursing Students

No notifications.

Disclaimer: This essay has been written by a student and not our expert nursing writers. View professional sample essays here.

View full disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NursingAnswers.net. This essay should not be treated as an authoritative source of information when forming medical opinions as information may be inaccurate or out-of-date.

Postpartum Depression: An Important Issue In Women’s Health

Info: 2066 words (8 pages) Nursing Essay Published: 29th May 2020

Reference this

Tagged: mental health depression PPD

If you need assistance with writing your nursing essay, our professional nursing essay writing service is here to help!

Our nursing and healthcare experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have, from simple essay plans, through to full nursing dissertations.

- Hantsoo, Liisa, et al. “A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial of Sertraline for Postpartum Depression.” SpringerLink , Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 31 Oct. 2014, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-013-3316-1.

- Hyland, Kristina. “Postpartum Depression Research Paper.” LinkedIn SlideShare , 15 Nov. 2015, www.slideshare.net/KristinaHyland/postpartum-depression-research-paper-55121451.

- National Institute of Mental Health, www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/postpartum-depression-facts/index.shtmlTables.

- “Postnatal Depression Has Life-Long Impact on Mother-Child Relations.” ScienceDaily , ScienceDaily, 20 Feb. 2018, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/02/180220122917.htm.

- “Postpartum Depression.” Mayo Clinic , Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1 Sept. 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/postpartum-depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20376617.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

- Nursing Essay Writing Service

- Nursing Dissertation Service

- Reflective Writing Service

Related Content

Content relating to: "PPD"

Post-partum or post-natal depression (PPD) affects around 10-15% of mothers having their first baby. Depression during this time is seen as putting the mother at risk for the onset of a serious chronic mood disorder. Symptoms can initially include irritability, tearfulness, insomnia, hypochondriasis, headache and impairment of concentration.

Related Articles

Abstract The purpose of this paper is to educate and inform the audience of a condition known as Postpartum depression (PPD). Throughout this text I will be identifying what exactly PPD is, causes and...

Reflection on Pregnancy and Childbirth

Explain Why the Critical Factors Influencing the Course of Pregnancy Including Several Dimensions such as Social, Biological and Psychological Factors The period in the uterus before conception is a...

Intervention Strategies for Post Partum Depression

More than 1 in 10 women in the United Kingdom develop a mental illness during pregnancy or in the first year after giving birth, according to research by the Centre for Mental Health and London ...

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on the NursingAnswers.net website then please:

Our academic writing and marking services can help you!

- Marking Service

- Samples of our Work

- Full Service Portfolio

Related Lectures

Study for free with our range of nursing lectures!

- Drug Classification

- Emergency Care

- Health Observation

- Palliative Care

- Professional Values

Write for Us

Do you have a 2:1 degree or higher in nursing or healthcare?

Study Resources

Free resources to assist you with your nursing studies!

- APA Citation Tool

- Example Nursing Essays

- Example Nursing Assignments

- Example Nursing Case Studies

- Reflective Nursing Essays

- Nursing Literature Reviews

- Free Resources

- Reflective Model Guides

- Nursing and Healthcare Pay 2021

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Call the OWH HELPLINE: 1-800-994-9662 9 a.m. — 6 p.m. ET, Monday — Friday OWH and the OWH helpline do not see patients and are unable to: diagnose your medical condition; provide treatment; prescribe medication; or refer you to specialists. The OWH helpline is a resource line. The OWH helpline does not provide medical advice.

Please call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room if you are experiencing a medical emergency.

Postpartum depression

Your body and mind go through many changes during and after pregnancy. If you feel sad, anxious, or overwhelmed or feel like you don’t love or care for your baby and these feelings last longer than 2 weeks during or after pregnancy, you may have postpartum depression. Treatment for depression, such as therapy or medicine, works and can help you and your baby be as healthy as possible in the future.

What is postpartum depression?

“Postpartum” means the time after having a baby. Some women get the “baby blues,” or feel sad, worried, or tired within a few days of giving birth. For many women, the baby blues go away in a few days. If these feelings don’t go away or you feel sad, hopeless, or anxious for longer than 2 weeks, you may have postpartum depression. Feeling hopeless after childbirth is not a regular or expected part of being a mother.

Postpartum depression is a serious mental health condition that involves the brain and affects your behavior and physical health. If you have depression, then sad and hopeless feelings don’t go away and can interfere with your day-to-day life. You might not feel connected to your baby, as if you are not the baby’s mother, or you might not love or care for the baby. These feelings can be mild to severe.

Mothers can also experience anxiety disorders during or after pregnancy.

How common is postpartum depression?

Depression is a common problem after pregnancy . One in 8 new mothers report experiencing symptoms of postpartum depression in the year after childbirth. 1

How do I know if I have postpartum depression?

Some normal changes after pregnancy can cause symptoms similar to those of depression. Many mothers feel overwhelmed when a new baby comes home. But if you have any of the following symptoms of depression for more than 2 weeks, call your doctor, nurse, or midwife:

- Feeling angry or moody

- Feeling sad or hopeless

- Feeling guilty, shameful, or worthless

- Eating more or less than usual

- Sleeping more or less than usual

- Unusual crying or sadness

- Loss of interest, joy, or pleasure in thing you used to enjoy

- Withdrawing from friends and family

- Possible thoughts of harming the baby or yourself

Some women don’t tell anyone about their symptoms. New mothers may feel embarrassed, ashamed, or guilty about feeling depressed when they are supposed to be happy. They may also worry they will be seen as bad mothers. Any woman can become depressed during pregnancy or after having a baby. It doesn’t mean you are a bad mom. You don’t have to suffer. There is help. Your doctor can help you figure out whether your symptoms are caused by depression or something else.

What causes postpartum depression?

The exact cause of PPD is not known and many different factors are likely to contribute to someone developing PPD. Hormonal changes may trigger symptoms of postpartum depression. When you are pregnant, levels of the female hormones estrogen and progesterone are the highest they’ll ever be. In the first 24 hours after childbirth, hormone levels quickly drop back to normal, pre-pregnancy levels. Researchers think this sudden change in hormone levels may lead to depression . 2 This is similar to hormone changes before a woman’s period but involves much more extreme swings in hormone levels.

Levels of thyroid hormones may also drop after giving birth. The thyroid is a small gland in the neck that helps regulate how your body uses and stores energy from food. Low levels of thyroid hormones can cause symptoms of depression. A simple blood test can tell whether this condition is causing your symptoms. If so, your doctor can prescribe thyroid medicine.

Are some women more at risk of postpartum depression?

Yes. You may be more at risk of postpartum depression if you:

- Had depression before or during pregnancy

- Have a family history of depression

- Experienced abuse or adversity as a child

- Had a difficult or traumatic birth

- Had problems with a previous pregnancy or birth

- Have little or no support from family, friends, or partners

- If you are now or have experienced domestic violence

- Have relationship struggles, money problems, or experience other stressful life events

- Are under the age of 20

- Have a hard time breastfeeding

- Have a baby that was born prematurely and/or has special health care needs

- Had an unplanned pregnancy

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that doctors look for and ask about symptoms of depression during and after pregnancy, regardless of a woman’s risk of depression. 4

What is the difference between “baby blues” and postpartum depression?

Many women have the baby blues in the days after childbirth. If you have the baby blues, you may:

- Have mood swings

- Feel sad, anxious, or overwhelmed

- Have crying spells

- Lose your appetite

- Have trouble sleeping

The baby blues usually go away within a few days. The symptoms of postpartum depression last longer, are more severe, and may require treatment by a health care professional. Postpartum depression usually begins within the first month after birth.

What should I do if I have symptoms of postpartum depression?

Call your doctor, nurse, midwife, or pediatrician if:

- Your baby blues symptoms don’t go away after 2 weeks or are very intense

- Symptoms of depression begin within 1 year of delivery and last more than 2 weeks

- It is difficult to work or get things done at home

- You cannot care for yourself or your baby (e.g., eating, sleeping, bathing)

- You have thoughts about hurting yourself or your baby

Ask your partner or a loved one to call for you if necessary. Your doctor, nurse, or midwife can ask you questions to test for depression. They can also refer you to a mental health professional for help and treatment.

What can I do at home to feel better while seeing a doctor for postpartum depression?

Here are some ways to begin feeling better or getting more rest, in addition to talking to a health care professional:

- Rest as much as you can. Sleep when the baby is sleeping.

- Don’t try to do too much or to do everything by yourself. Ask your partner, family, and friends for help.

- Make time to go out, visit friends, or spend time alone with your partner.

- Talk about your feelings with your partner, supportive family members, and friends.

- Talk with other mothers so that you can learn from their experiences.

- Join a support group. Ask your doctor or nurse about groups in your area.

- Don’t make any major life changes right after giving birth. More major life changes in addition to a new baby can cause unneeded stress. Sometimes big changes can’t be avoided. When that happens, try to arrange support and help in your new situation ahead of time.

It can also help to have a partner, a friend, or another caregiver who can help take care of the baby while you are depressed. If you are feeling depressed during pregnancy or after having a baby, don’t suffer alone. Tell a loved one and call your doctor right away.

How is postpartum depression treated?

Working with a health care professional is a good way to create a plan that will work for you. Here are some ways to get help—they can be used alone or together:

- Therapy: Counseling or therapy sessions with a mental health professional can help you understand and cope with your emotions and challenges.

- Support groups: Joining a support group of others experiencing PPD can provide comfort and understanding.

- Self-care: Taking care of yourself is important. Do your best to get enough rest, eat food with a lot of nutrients like fresh produce and whole grains, be physically active, and ask for help when needed.

- Social support: Reach out to family, friends, or other people you trust who can offer advice or support.

- Medication: In some cases, medicine may be prescribed to help manage symptoms. The most common type is antidepressants. Antidepressants can help relieve symptoms of depression and some can be taken while you're breastfeeding. Antidepressants may take several weeks to start working.

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also approved a medicine called brexanolone to treat postpartum depression in adult women . 6 Brexanolone is given by a doctor or nurse through an IV for 2½ days (60 hours). Because of the risk of side effects, this medicine can only be given in a clinic or office while you are under the care of a doctor or nurse. Brexanolone may not be safe to take while pregnant or breastfeeding. Zuranolone, the first oral medication approved to treat postpartum depression may be another option.

These treatments can be used alone or together. Talk with your doctor or nurse about the benefits and risks of taking medicine to treat depression when you are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Having depression can affect your baby. Getting treatment is important for you and your baby. Getting help is a sign of strength.

What can happen if postpartum depression is not treated?

Untreated postpartum depression can affect your ability to parent. You may:

- Not have enough energy

- Have trouble focusing on the baby's needs and your own needs

- Not be able to care for your baby

- Have a higher risk of attempting suicide

Feeling bad about yourself can make depression worse. It is important to reach out for help if you feel depressed .

Researchers believe postpartum depression in a mother can affect the healthy development of her child which can cause: 7

- Delays in language development and problems learning

- Problems with mother-child bonding

- Behavior problems

- More crying or agitation

- Shorter height 8 and higher risk of obesity in pre-schoolers 9

- Problems dealing with stress and adjusting to school and other social situations 10

Did we answer your question about postpartum depression?

The resources below can help you learn more about PPD and can guide you in finding additional help.

- Call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 for free access to a trained crisis counselor who can provide you with support and connect you with additional help and resources. If you’re deaf or hard of hearing, use your preferred relay service or dial 711 then 988 .

- Call or text the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline at 1-833-TLC-MAMA ( 1-833-852-6262 ) for 24/7 free access to professional counselors. If you’re deaf or hard of hearing, use your preferred relay service or dial 711 then 1-833-852-6262 .

- Call or text “Help” to the Postpartum Support International helpline at 1-800-944-4773 for PPD information, resources, and support groups for women, partners, and supporters.

- Ask a health care professional or find a local health center.

- Reach out to local organizations like social service agencies, family resource centers, libraries, community centers, or places of worship.

- Look for support groups in your area, such as new moms’ groups, breastfeeding support groups, or a baby café. See if there are mother/baby exercise programs in your community.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Reproductive Health. (2020). Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/prams/prams-data/mch-indicators/states/pdf/2020/All-Sites-PRAMS-MCH-Indicators-508.pdf . Accessed on June 5th, 2023.

- Schiller, C.E., Meltzer-Brody, S., Rubinow, D.R. (2014). The Role of Reproductive Hormones in Postpartum Depression . CNS Spectrums; 20(1): 48–59.

- Sit, D.K., Wisner, K.L. (2009). The Identification of Postpartum Depression . Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology; 52(3): 456–468.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Depression in Adults: Screening .

- Alhusen, J.L., Alvarez, C. (2016). Perinatal depression . The Nurse Practitioner; 41(5): 50–55.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019). FDA approves first treatment for post-partum depression .

- Stein, A., Perason, R.M., Goodman, S.H., Rapa, E., Rahman, A., McCallum, M., et al. (2014). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child . Lancet; 384(9956): 1800–1819.

- Surkan, P.J., Ettinger, A.K., Hock, R.S., Ahmed, S., Strobino, D.M., Minkovitz, C.S. (2014). Early maternal depressive symptoms and child growth trajectories: a longitudinal analysis of a nationally representative US birth cohort . BMC Pediatrics; 14: 185.

- Benton, P.M., Skouteris, H., Hayden, M. (2015). Does maternal psychopathology increase the risk of pre-schooler obesity? A systematic review . Appetite; 87(1): 259–282.

- Korhonen, M., Luoma, I., Salmelin, R., Tamminen, T. (2014). Maternal depressive symptoms: Associations with adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems and social competence . Nordic Journal of Psychiatry; 68(5): 323–332.

To learn more about postpartum depression and access educational resources, visit our Talking Postpartum Depression campaign page.

- HHS Non-Discrimination Notice

- Language Assistance Available

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Disclaimers

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Use Our Content

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Kreyòl Ayisyen

A federal government website managed by the Office on Women's Health in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1101 Wootton Pkwy, Rockville, MD 20852 1-800-994-9662 • Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. ET (closed on federal holidays).

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Neurology & Nervous System Diseases — Postpartum Depression

Essay Examples on Postpartum Depression

Depression: an informative exploration, postpartum depression and anxiety disorders in women, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Suffering in Silence: The Development of Postpartum Depression

Jane's postpartum depression in the yellow wallpaper by charlotte perkins gilman, the factors of postpartum depression, the effects of postpartum depression in the poem the yellow wallpaper by charlotte perkins gilman, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Postpartum Depression Among Canadian Women

Bond between mother and child: postpartum depression in immigrants, relevant topics.

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Sleep Deprivation

- Drug Addiction

- Stress Management

- Healthy Food

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Postpartum depression

The birth of a baby can start a variety of powerful emotions, from excitement and joy to fear and anxiety. But it can also result in something you might not expect — depression.

Most new moms experience postpartum "baby blues" after childbirth, which commonly include mood swings, crying spells, anxiety and difficulty sleeping. Baby blues usually begin within the first 2 to 3 days after delivery and may last for up to two weeks.

But some new moms experience a more severe, long-lasting form of depression known as postpartum depression. Sometimes it's called peripartum depression because it can start during pregnancy and continue after childbirth. Rarely, an extreme mood disorder called postpartum psychosis also may develop after childbirth.

Postpartum depression is not a character flaw or a weakness. Sometimes it's simply a complication of giving birth. If you have postpartum depression, prompt treatment can help you manage your symptoms and help you bond with your baby.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Your Baby's First Years

Symptoms of depression after childbirth vary, and they can range from mild to severe.

Baby blues symptoms

Symptoms of baby blues — which last only a few days to a week or two after your baby is born — may include:

- Mood swings

- Irritability

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Reduced concentration

- Appetite problems

- Trouble sleeping

Postpartum depression symptoms

Postpartum depression may be mistaken for baby blues at first — but the symptoms are more intense and last longer. These may eventually interfere with your ability to care for your baby and handle other daily tasks. Symptoms usually develop within the first few weeks after giving birth. But they may begin earlier — during pregnancy — or later — up to a year after birth.

Postpartum depression symptoms may include:

- Depressed mood or severe mood swings

- Crying too much

- Difficulty bonding with your baby

- Withdrawing from family and friends

- Loss of appetite or eating much more than usual

- Inability to sleep, called insomnia, or sleeping too much

- Overwhelming tiredness or loss of energy

- Less interest and pleasure in activities you used to enjoy

- Intense irritability and anger

- Fear that you're not a good mother

- Hopelessness

- Feelings of worthlessness, shame, guilt or inadequacy

- Reduced ability to think clearly, concentrate or make decisions

- Restlessness

- Severe anxiety and panic attacks

- Thoughts of harming yourself or your baby

- Recurring thoughts of death or suicide

Untreated, postpartum depression may last for many months or longer.

Postpartum psychosis

With postpartum psychosis — a rare condition that usually develops within the first week after delivery — the symptoms are severe. Symptoms may include:

- Feeling confused and lost

- Having obsessive thoughts about your baby

- Hallucinating and having delusions

- Having sleep problems

- Having too much energy and feeling upset

- Feeling paranoid

- Making attempts to harm yourself or your baby

Postpartum psychosis may lead to life-threatening thoughts or behaviors and requires immediate treatment.

Postpartum depression in the other parent

Studies show that new fathers can experience postpartum depression, too. They may feel sad, tired, overwhelmed, anxious, or have changes in their usual eating and sleeping patterns. These are the same symptoms that mothers with postpartum depression experience.

Fathers who are young, have a history of depression, experience relationship problems or are struggling financially are most at risk of postpartum depression. Postpartum depression in fathers — sometimes called paternal postpartum depression — can have the same negative effect on partner relationships and child development as postpartum depression in mothers can.

If you're a partner of a new mother and are having symptoms of depression or anxiety during your partner's pregnancy or after your child's birth, talk to your health care provider. Similar treatments and supports provided to mothers with postpartum depression can help treat postpartum depression in the other parent.

When to see a doctor

If you're feeling depressed after your baby's birth, you may be reluctant or embarrassed to admit it. But if you experience any symptoms of postpartum baby blues or postpartum depression, call your primary health care provider or your obstetrician or gynecologist and schedule an appointment. If you have symptoms that suggest you may have postpartum psychosis, get help immediately.

It's important to call your provider as soon as possible if the symptoms of depression have any of these features:

- Don't fade after two weeks.

- Are getting worse.

- Make it hard for you to care for your baby.

- Make it hard to complete everyday tasks.

- Include thoughts of harming yourself or your baby.

If you have suicidal thoughts

If at any point you have thoughts of harming yourself or your baby, immediately seek help from your partner or loved ones in taking care of your baby. Call 911 or your local emergency assistance number to get help.

Also consider these options if you're having suicidal thoughts:

- Seek help from a health care provider.

- Call a mental health provider.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential. The Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in the U.S. has a Spanish language phone line at 1-888-628-9454 (toll-free).

- Reach out to a close friend or loved one.

- Contact a minister, spiritual leader or someone else in your faith community.

Helping a friend or loved one

People with depression may not recognize or admit that they're depressed. They may not be aware of signs and symptoms of depression. If you suspect that a friend or loved one has postpartum depression or is developing postpartum psychosis, help them seek medical attention immediately. Don't wait and hope for improvement.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

There is no single cause of postpartum depression, but genetics, physical changes and emotional issues may play a role.

- Genetics. Studies show that having a family history of postpartum depression — especially if it was major — increases the risk of experiencing postpartum depression.

- Physical changes. After childbirth, a dramatic drop in the hormones estrogen and progesterone in your body may contribute to postpartum depression. Other hormones produced by your thyroid gland also may drop sharply — which can leave you feeling tired, sluggish and depressed.

- Emotional issues. When you're sleep deprived and overwhelmed, you may have trouble handling even minor problems. You may be anxious about your ability to care for a newborn. You may feel less attractive, struggle with your sense of identity or feel that you've lost control over your life. Any of these issues can contribute to postpartum depression.

Risk factors

Any new mom can experience postpartum depression and it can develop after the birth of any child, not just the first. However, your risk increases if:

- You have a history of depression, either during pregnancy or at other times.

- You have bipolar disorder.

- You had postpartum depression after a previous pregnancy.

- You have family members who've had depression or other mood disorders.

- You've experienced stressful events during the past year, such as pregnancy complications, illness or job loss.

- Your baby has health problems or other special needs.

- You have twins, triplets or other multiple births.

- You have difficulty breastfeeding.

- You're having problems in your relationship with your spouse or partner.

- You have a weak support system.

- You have financial problems.

- The pregnancy was unplanned or unwanted.

Complications

Left untreated, postpartum depression can interfere with mother-child bonding and cause family problems.

- For mothers. Untreated postpartum depression can last for months or longer, sometimes becoming an ongoing depressive disorder. Mothers may stop breastfeeding, have problems bonding with and caring for their infants, and be at increased risk of suicide. Even when treated, postpartum depression increases a woman's risk of future episodes of major depression.

- For the other parent. Postpartum depression can have a ripple effect, causing emotional strain for everyone close to a new baby. When a new mother is depressed, the risk of depression in the baby's other parent may also increase. And these other parents may already have an increased risk of depression, whether or not their partner is affected.

- For children. Children of mothers who have untreated postpartum depression are more likely to have emotional and behavioral problems, such as sleeping and eating difficulties, crying too much, and delays in language development.

If you have a history of depression — especially postpartum depression — tell your health care provider if you're planning on becoming pregnant or as soon as you find out you're pregnant.

- During pregnancy, your provider can monitor you closely for symptoms of depression. You may complete a depression-screening questionnaire during your pregnancy and after delivery. Sometimes mild depression can be managed with support groups, counseling or other therapies. In other cases, antidepressants may be recommended — even during pregnancy.

- After your baby is born, your provider may recommend an early postpartum checkup to screen for symptoms of postpartum depression. The earlier it's found, the earlier treatment can begin. If you have a history of postpartum depression, your provider may recommend antidepressant treatment or talk therapy immediately after delivery. Most antidepressants are safe to take while breastfeeding.

- Depressive disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association; 2022. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed May 9, 2022.

- Postpartum depression. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/mental-health/mental-health-conditions/postpartum-depression. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Depression among women. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/depression/index.htm. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- What is peripartum depression (formerly postpartum)? American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/postpartum-depression/what-is-postpartum-depression. Accessed Nov. 18, 2022.

- Viguera A. Postpartum unipolar depression: Epidemiology, clinical features, assessment, and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Nov. 18, 2022.

- Viguera A. Mild to moderate postpartum unipolar major depression: Treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 6, 2022.

- Viguera A. Severe postpartum unipolar major depression: Choosing treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 6, 2022.

- Faden J, et al. Intravenous brexanolone for postpartum depression: What it is, how well does it work, and will it be used? Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 2020; doi:10.1177/2045125320968658.

- FAQs. Postpartum depression. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/postpartum-depression. Accessed May 6, 2022.

- Suicide prevention. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/suicide-prevention. Accessed May 6, 2022.

- Postpartum depression. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gynecology-and-obstetrics/postpartum-care-and-associated-disorders/postpartum-depression#. Accessed May 6, 2022.

- AskMayoExpert. Depression in pregnancy and postpartum. Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Postpartum care of the mother. In: Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 8th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- Kumar SV, et al. Promoting postpartum mental health in fathers: Recommendations for nurse practitioners. American Journal of Men's Health. 2018; doi:10.1177/1557988317744712.

- Scarff JR. Postpartum depression in men. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 2019;16:11.

- Bergink V, et al. Postpartum psychosis: Madness, mania, and melancholia in motherhood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016; doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16040454.

- Yogman M, et al. Fathers' roles in the care and development of their children: The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016; doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1128.

- FDA approves first treatment for post-partum depression. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-post-partum-depression. Accessed May 6, 2022.

- Deligiannidis KM, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021; doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1559.

- Betcher KM (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 10, 2022.

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. https://988lifeline.org/. Accessed Nov. 18, 2022.

Associated Procedures

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Postpartum depression is more than baby blues Feb. 02, 2023, 03:00 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

A comprehensive analysis of post-partum depression risk factors: the role of socio-demographic, individual, relational, and delivery characteristics.

- 1 Department of Surgical, Medical and Molecular Pathology and Critical Care Medicine, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

- 2 Department of Educations, Languages, Intercultures, Literatures and Psychology, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

- 3 Division of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

Postpartum depression is a common and complex phenomenon that can cause relevant negative outcomes for children, women and families. Existing literature highlights a wide range of risk factors. The main focus of this paper is to jointly investigate different types of risk factors (socio-demographic, psychopathological, relational, and related to labor and birth experience) in post-partum depression onset in women during first-child pregnancy, identifying which of these are the most important predictors. A cohort longitudinal study was conducted on 161 Italian nulliparous low-risk women ( M age = 31.63; SD = 4.88) without elective cesarean. Data was collected at three different times: Socio-demographic, prenatal anxiety and depression, and quality of close relationship network (with mother, father and partner, and the prenatal attachment to child) were assessed at T1 (week 31–32 of gestation); clinical data on labor and childbirth (mode and typology of delivery, duration of labor, duration of eventual administration of epidural analgesia, and child's APGAR index at birth) were registered at T2 (the day of childbirth); and the degree of post-natal depression symptomatology was measured at T3 (1 month after birth). Postpartum depression is associated with several risk factors (woman's age, woman's prenatal psychopathological characteristics, the level of prenatal attachment to child, the quality of romantic relationship, and some clinical delivery difficulties). Overall, the level of prenatal attachment to child was the most important predictor of post-partum depression. These findings emphasize the very important role of prenatal attachment for the onset of postpartum depression and the need to promote adequate and targeted prevention interventions. Limitations, strengths, and theoretical and clinical implications are discussed.

Introduction

For a woman, the gestation of her first child has been identified as a central life event ( 1 ). From a psychological perspective, in fact, the pregnancy of the first baby involves the transition to motherhood, a major developmental period with important implications for mothers, for the infant-mother relationship, and the infant's development ( 2 ). During the first pregnancy, a woman's maternal identity develops through the reorganization of mental self-representation and the elaboration of other significant relationships ( 3 , 4 ). The woman's mental self-representation enriches with the maternal component, thus leading her to review the relationship with her own mother; the mental couple image gradually modifies with integration of the family image, and the marital relationship is reorganized with the parental component. With the birth of the first child, the quality of the couple relationship may undergo temporary changes that are influenced by the ability of the parents to adapt to new needs ( 5 ).

The transition to parenthood (transition to parenthood—TTP) has often been associated with marital crisis, and the premise in literature was that parenthood creates serious individual and relationship distress ( 6 , 7 ). Parenting can be an improvement factor for some couple relationships; however, it can also be disruptive and increase problems ( 8 ). While some couples may develop new skills in resolving difficulties, others find themselves running aground trying to develop these skills ( 6 ).

All the above physical, psychological, and relational changes that occur during the perinatal period may increase the risk for maternal emotional vulnerability, such as depressed emotions. The DSM-5 proposes the term “peripartum onset” as a major depressive episode during pregnancy or in the weeks or months following delivery ( 9 ). This condition is characterized by sad mood, anxiety, irritability, lack of positive emotions, loss of pleasure, interests and energy, decreased appetite, inability to cope, fear of hurting self and baby, and suicidal thoughts ( 10 , 11 ). Both anxiety and depression can occur in the perinatal period (up to 1 year after delivery) ( 9 ) and these conditions present high rates of co-morbidity ( 12 ). The first weeks immediately after childbirth are the most critical ( 13 ), and although the increased vulnerability continues for the following 6 months ( 14 – 16 ), post-partum depression (PPD) generally occurs within the first month after delivery ( 9 ).

This vulnerability is higher for primiparous mothers, who present an increased risk for depression in the postpartum period ( 12 , 17 , 18 ), especially in the first 90 days after delivery ( 19 ). Although contrasting results emerged about the prevalence of postpartum depression in relation to parity ( 20 , 21 ), studies conducted in the European context showed that the prevalence for PPD in primiparas was 11.8 vs. 8.6% in multiparas ( 21 ).

In fact, maternal inexperience leads new mothers to have greater difficulty in early interactions with their children, and research has reported that the effect of maternal depression is greater in nulliparas compared to multiparas ( 22 ).

Although from a psychiatric perspective postpartum depression is no longer classified as a distinct entity, from a psychological perspective, depression occurring during the postpartum period has particular relevance in a woman's life.

In fact, it enhances the risk of a multitude of negative consequences for children, women, and families, including poor infant physical health and more frequent sickness, and physiological, psychological, emotional, and psychomotor delays during infancy and early childhood ( 23 ).

Moreover, PPD can negatively affect the ability and the availability of women to adequately take care of their children. Henderson et al. ( 24 ) have shown the important negative outcomes that PPD can have on mother-infant interactions, the child's growth, and the tendency to quit breastfeeding earlier. Moreover, children of mothers with PPD tend to establish insecure attachment bonds and develop social difficulties with peers ( 25 , 26 ).

Because of these relevant consequences, it is important to identify the risk factors that can be involved in the development of PPD in first-time mothers.

Several factors, both internal and external, have been found to be related to PPD, and it is plausible that a complex interplay of these can be the cause of greater vulnerability ( 27 ), especially in women during their first pregnancy, compared to those who already have a child. Alongside psychological risk factors, such as a lifetime history of depression, and a presence of antenatal depression and prenatal anxiety ( 28 , 29 ), many authors have shown that relational variables constitute significant risk factors for post-partum depression development. Problems in maternal and romantic relationships, such as marital instability, and low level of maternal ( 30 , 31 ) and marital support ( 32 ) have been found to be linked with PPD. Priel and Besser ( 33 ) have also found that antenatal attachment was closely linked to PPD. A higher level of antenatal attachment to child predicted a lower level of depressive symptomatology after birth. The presence of stressful life events, or the lack of social support from peer and health professionals, can foster the subsequent development of PPD ( 34 – 36 ).

There are other clinical aspects linked to pregnancy and delivery that are associated to the PPD condition. A complicated labor and birth characterized by longer length of labor and greater pain, or medical intervention during delivery, can result in negative consequences, varying from maternal distress to PPD ( 31 , 37 ). Given that the nulliparous tend to be less self-confident in the maternal role, and that being less self-confident has been associated with postpartum depression ( 38 ), labor and delivery complications can be particularly difficult for first-time mothers.

Finally, some socio-demographic characteristics, such as a young age, or low level of education, or low income, may be considered linked to a higher probability of developing PPD ( 39 , 40 ).

Despite the relevance of these risk factors, most studies have focused on psychopathology and social network aspects linked to maternal and romance relationships, and less attention has been directed to the exploration of these factors jointly.

The aims of this study were: (1) to confirm previous results exploring the role that several sets of variables, such as socio-demographic, individual, relational, and related to delivery characteristics, separately considered, play as risk factors for the onset of postpartum depression; and (2) to verify which, among the above risk factors, have a more significant influence when they are considered together.

In accordance with literature, it was hypothesized that: (1) young age, low level of education, low employment status, and not planned pregnancy, could positively predict levels of PPD; (2) prenatal anxiety and depression positively predict PPD; (3) an affectionate prenatal attachment, and a good quality romantic and parental relationship negatively predict PPD; (4) a more complicated labor (in terms of duration and duration of epidural and oxytocin administration), the modality of delivery (cesarean section vs. vaginal birth) and a worse index of newborn well-being (in terms of lower Apgar score) positively predict PPD. No hypotheses were developed about the strongest predictor for PPD.

Materials and Methods

Procedure and participants.

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for the ethical treatment of human participants of the Italian Psychological Association. The Ethical Committee of Azienda USL 4 Prato, Italy, had previously approved the study (no 780/2013). Data were collected during 2014 in the maternity ward of a public hospital of the metropolitan area of Prato (Italy), a unit with about 1,130 deliveries per year (69% Italian women), from January to December 2014, during delivery preparation courses organized for pregnant women (>30 weeks of gestation).

A cohort longitudinal study was carried out. Data were collected at three different time points: (1) 31–32 week of gestation; (2) the day of delivery; and (3) 1 month after childbirth.

Inclusion criteria were: Italian women, age >18 years, physically and psychologically healthy nulliparous women with singleton low-risk pregnancies, gestational age >31 weeks. Exclusion criteria were: twin pregnancy, maternal pathologies during pregnancy, fetal pathologies, the presence of depressive pathologies documented in clinical records, and planned elective cesarean. Planned elective cesarean was an exclusion criterium because we were interested in examining the roles of labor and delivery as predictors of PPD. Therefore, we excluded from the study women who underwent planned elective cesarean, but not those who experienced emergency cesarean after labor.

The participants ( n = 191) were informed about the aims of the study and signed a written informed consent form. They could withdraw from participation at any time. Ninety-four percent of the women who were contacted consented to participate in the survey ( n = 179) and, of them, 90% completed the entire follow-up (Time 1, 2, and 3). At T1 we recruited 179 women, but by T3 we lost 18 women who did not return the completed questionnaire. The final sample consisted of 161 nulliparous pregnant women aged 18–42 years ( M = 31.63, SD = 4.88). Our sample is representative regarding both size and age of the general population of women giving birth in Prato that meet our inclusion criteria.

At time 1, all participants received a battery of questionnaires for the collection of socio-demographic, clinical, psychological and relational data. In particular:

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Measures

Participants provided their age, educational level, work status, marital status, information about the number of years of their couple relationship, and information about planned or not pregnancy.

Psychological Measures

Participants were asked to complete psychological questionnaires to assess psychopathological characteristics. To assess the women's anxiety level, the State Anxiety Inventory (STAI_Y2) ( 41 , 42 ) was used. This questionnaire is the most widely used measure of anxiety during pregnancy, especially in association with postnatal depression ( 43 ). The STAI_Y2 is a 20-item self-report questionnaire asking to report how often the anxiety state was experienced. Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 4 (very often) The total score is obtained by summing all items, after some items are overturned, and can range from 20 to 80. A high score indicates a high level of anxiety. For the current study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.90.

To detect the level of women's depression, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) ( 44 , 45 ) was used. The BDI is a 21-item self-report inventory used for measuring the severity of symptoms. Each item had a set of four responses ranging in intensity from 0 to 3. The total score is obtained by summing all items and can range from 0 to 63. High scores indicate high depressive symptomatology. In the present sample, Cronbach's value was 0.84.

Relational Measures

All women were asked to complete four questionnaires assessing the quality of their close relationship network, with their mother, father and partner, and the level of their prenatal attachment to child. In particular, the quality of women's relationships with mothers and fathers was assessed using the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) ( 46 , 47 ). The PBI consists of two parallel versions of 21 items, ranging from 0 (Very likely) to 3 (Very unlikely), which assessed three dimensions: Care, Encouragement toward autonomy, and Overprotection. In the present sample, Cronbach's values for the paternal version were 0.98, 0.98, and 0.96 for Care, Encouragement toward autonomy, and Overprotection, respectively. For the maternal version, Cronbach's values for Care, Encouragement toward autonomy, and Overprotection were 0.98, 0.96, and 0.87, respectively. In this study, we used a global dimension of the relationship quality, summing the above three dimensions, according to the procedure described in the results section. The total score for PBI is obtained by summing all items and can range from 0 to 63. High scores on this dimension indicate that the women perceive a good quality of their maternal and paternal relationships.

The quality of the women's romantic relationships was assessed using the Romance Qualities Scale (RQS) ( 48 ). The RQS is a 22-item self-report instrument, ranging from 1 (Absolutely false) to 5 (Absolutely true), which assesses five main qualitative dimensions of the relationship with partner (companionship, conflict, help, security and closeness) and a global score of the romantic relationship quality. The total score is obtained by summing all items and can range from 22 to 110. High scores on this dimension indicate that women perceive a good quality of their romantic relationships. In the present sample, Cronbach's value was 0.84.

The Prenatal Attachment Inventory (PAI) ( 49 , 50 ) was used to measure the mother's attachment bond to her child during pregnancy. The PAI is a self-report questionnaire with 21 items from 1 (Almost never) to 4 (Almost always). The total score is obtained by summing all items and can range from 21 to 84. High scores indicate a good quality of prenatal attachment bond. For the present sample, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.93.

At time 2, clinical information regarding labor, delivery and birth outcomes was extracted from hospital records after childbirth. In particular:

Labor measures including three indices: (a) modality of labor (induced vs. spontaneous); (b) duration of labor in hours; (c) administration of epidural analgesia in hours (no analgesia administration = 0).

Mode of delivery, recorded according to category: vaginal (natural and operative vaginal delivery) vs. emergency cesarean delivery.

Birth outcomes, assessed via APGAR scores at 1 min. APGAR score index at birth was determined by evaluating the newborn baby on: color, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone, respiration). Scores ≤3 are generally regarded as critically low, 4–6 fairly low, and 7–10 generally normal.

At time 3, women were requested to fill out a psychological questionnaire to assess the degree of postnatal depression symptomatology. Diagnosing depression in post-partum may be particularly challenging due to the overlap of diagnostic depressive symptoms with those of a normal post-partum period for women (e.g., fatigue, decreased libido, and sleep or appetite change). Nevertheless, as documented by several authors, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) ( 51 , 52 ), originally devised for the identification of postpartum depression disorders, allows us to measure affective aspects rather than physical symptoms of depression that may be affected by the perinatal period ( 52 ). The EPDS is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 10 items ranging from 0 to 3, according to increasing severity of the symptom. The total score is obtained by summing all items and can range from 0 to 30 with higher scores on this scale indicating higher levels of postnatal depression symptomatology. For the current sample, Cronbach's alpha was 0.88.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24 (2017). Frequency, means, standard deviation, and bivariate correlation were calculated for all variables. To determine the relationship between predictor variables and postpartum depression, linear regression analyses were separately undertaken for each set of risk factor variables considered.

Regarding parental relationships, we were interested in creating an aggregate score of the quality of maternal and paternal relationship. To verify the possibility to use a single score for the quality of maternal and paternal relationships to include in the regression analysis, two factorial analyses with the three dimensions of the PBI were conducted, separately for the mother and father versions.

Subsequently, to explore the stronger risk factors, a linear regression (stepwise method) was conducted with post-partum depression as the dependent variable, and the significant risk factors were entered as predictors. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

All the women had a middle or high socioeconomic level; 87% had a high school diploma or bachelor's degree (13% of women had a secondary school diploma, 54% had a high school diploma, and 33% a bachelor's degree or more) and 81.4% of the women had a job. Regarding marital status, 100% of participants lived with their partners, and 59.1% were married. The length of romantic relationships ranged from 1 to 17 years ( M = 6.25, SD = 3.81). Pregnancy was planned in 82.6%.

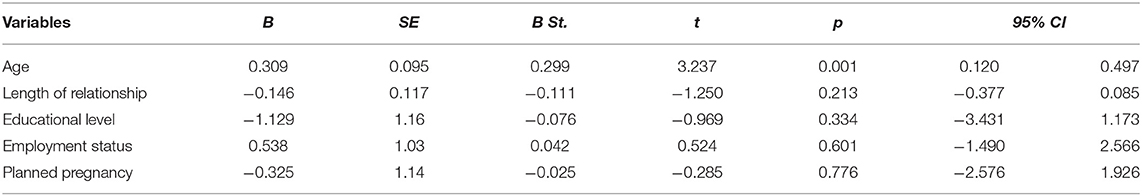

The regression analysis with socio-demographic characteristics as independent variables and the score of PPD as a dependent variable showed that the model composed by age, length of the romantic relationship, level of education (dummy variable: 1 = high school or university degree; 0 = middle school or elementary school degree), employment status (dummy variable: 1 = employed; 0 = unemployed), and planned pregnancy (dummy variable = 1 = non-planned; 0 = planned) explained only 6% of the variance ( Table 1 ). Specifically, data showed that the severity of PPD was positively affected by the age of women. On the contrary, the length of the relationship with partner, level of education, employment status, and planned pregnancy did not significantly affect the level of PPD.

Table 1 . Summary of the linear regression analysis with socio-demographical characteristics as independent variables for PPD score.

Psychopathological Characteristics and PPD Condition

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and pair-wise correlation coefficients for the two dimensions of psychopathological antenatal characteristics (anxiety and depression) and the PPD condition. A high level of PPD was associated with a high level of prenatal anxiety and depression. Moreover, prenatal anxiety and depression were significantly and positively correlated.

Table 2 . Descriptive statistics, correlations and summary of the linear regression analysis with psychopathological characteristics as independent variables for PPD score.

The linear regression performed with prenatal anxiety and depression on PPD score explained 38% of the variance (see Table 2 ). Both these variables positively affect the level of PPD.

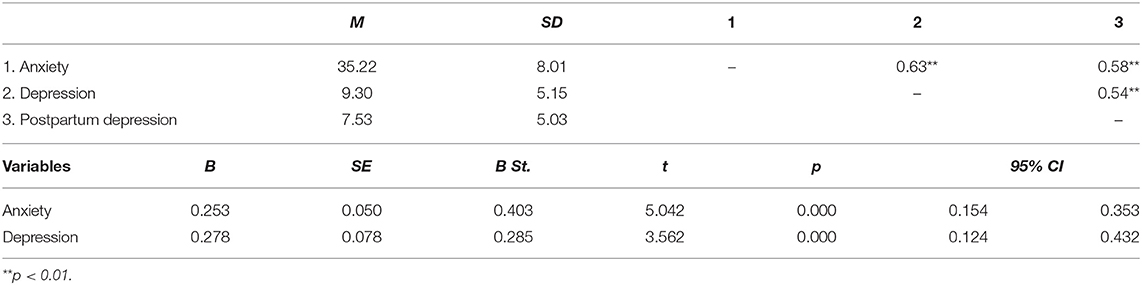

Close Relationships Network and PPD Condition

To obtain a global score of the women's relationship quality with their mothers and fathers, two factor analyses were conducted with the three dimensions of the PBI, for mother and father, separately. Because correlation analyses between the three dimensions of the PBI in relation to the maternal and paternal versions showed that the Overprotection dimension is negatively correlated with Care (maternal: r = −0.77; paternal: r = −0.58) and Encouragement toward autonomy (maternal: r = −0.89; paternal: r = −0.93) dimensions, the Overprotection score was reversed before carrying out the factorial analyses to obtain saturations of the same mark on the hypothetical common factor (the single score of the PBI measure).

The results of the factor analyses showed that the dimensions of the PBI (Care, Encouragement toward autonomy and Low Overprotection) loaded into a single factor for both the maternal and paternal versions. Specifically, regarding the maternal version, the three dimensions accounted for 86.15% of total variance. Regarding the paternal version, the three dimensions accounted for 83.99% of total variance.

In conclusion, both for the mother and father versions, high scores on this dimension express warm, positive and supportive parental behaviors, reflecting a good quality of parental relationships.

In Table 3 , the descriptive statistics of the close relationship variables and their pair-wise correlation coefficients with PPD are shown. The level of PPD was negatively and significantly correlated with the women's relationship quality with their mothers, fathers and romantic partners, and their prenatal attachment to child. Moreover, the prenatal attachment was positively correlated with the quality of the three close relationships (mother, father and partner). Finally, the quality of maternal relationship was significantly and positively correlated with the quality of paternal relationship. Given the high correlation between maternal and paternal relationships ( r = 0.87), in order to avoid multicollinearity problems, a single score of these aspects was calculated. In other words, we composed a score of parental relationship by calculating the mean of the two scores.

Table 3 . Descriptive statistics, correlations and summary of the linear regression analysis with the quality of parental, romantic and prenatal relationships as independent variables for PPD score.

The linear regression showed that the model composed by parental relationship, romantic relationship and prenatal attachment explained 52% of the variance (see Table 3 ). The quality of parental and romantic relationship and prenatal attachment to child seems to positively affect the level of PPD.

Labor, Delivery, and Birth Outcome Characteristics and PPD Condition

87.6% of the women had spontaneous labor, and in the remaining 12.4% labor was induced. 89.4% of women had vaginal deliveries, and 10.6% had emergency cesarean deliveries. Significant differences emerged with respect to PPD regarding the mode of labor [spontaneous vs. induced: t (159) = −5.311; p = 0.000] and mode [vaginal vs. cesarean: t (159) = 7.429; p = 0.000] of delivery. Specifically, women who had an induced labor showed a higher level of PPD than women who had a spontaneous one. In the same way, women who had a cesarean delivery reported a higher level of PPD than women with vaginal delivery.

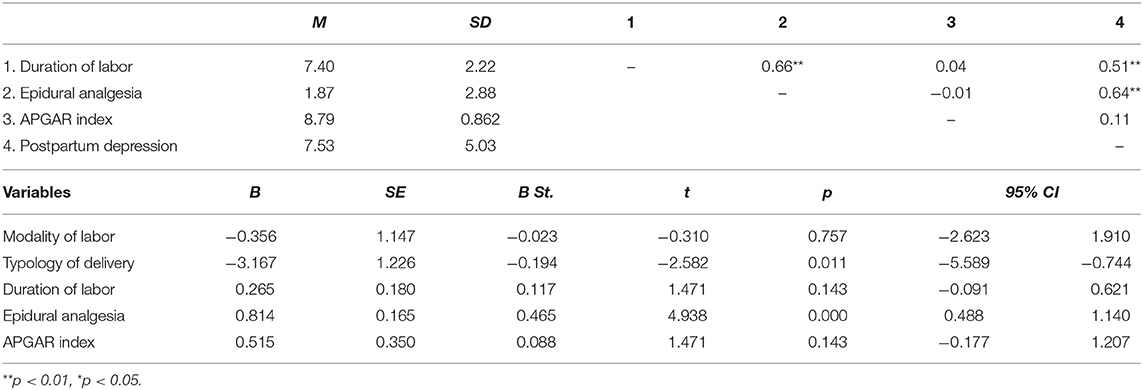

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of all continuous delivery variables.

Table 4 . Descriptive statistics, correlations and summary of the linear regression analysis with the delivery characteristics as independent variables for PPD score.

The level of PPD is positively and significantly correlated with the length of labor and the duration of the administration of epidural analgesia. On the contrary, the correlation between PPD and the child's APGAR index is not significant. Finally, the duration of labor is positively and significantly correlated with the duration of the administration of epidural analgesia.

Results of the linear regression showed that the model composed by the variables regarding labor, delivery and birth characteristics explained 44% of the variance (see Table 4 ). Specifically, cesarean delivery (dummy variable: 0 = cesarean delivery; 1 = vaginal delivery), and the duration of the administration of epidural analgesia seem to positively affect the severity of PPD. On the contrary, the results showed the no-significant influences of the modality of labor (dummy variable: 1 = induced labor; 0 = spontaneous labor) and the duration of labor, or the child's APGAR index, in affecting the severity of PPD.

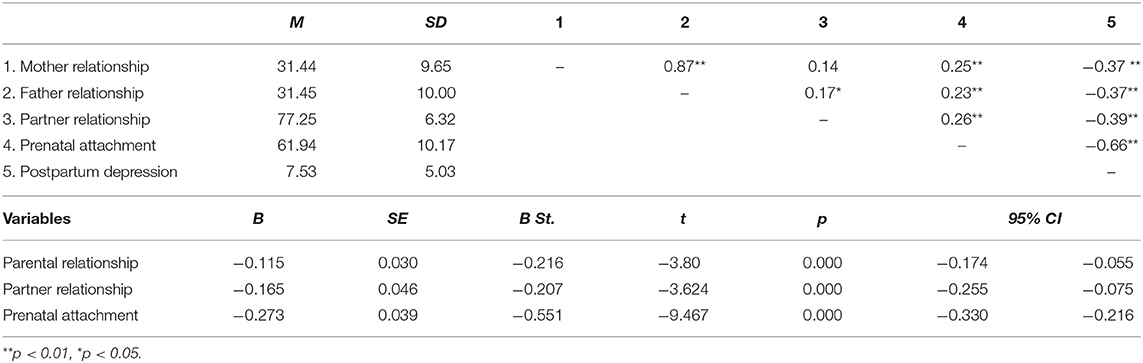

The Stronger Predictors of PPD Condition

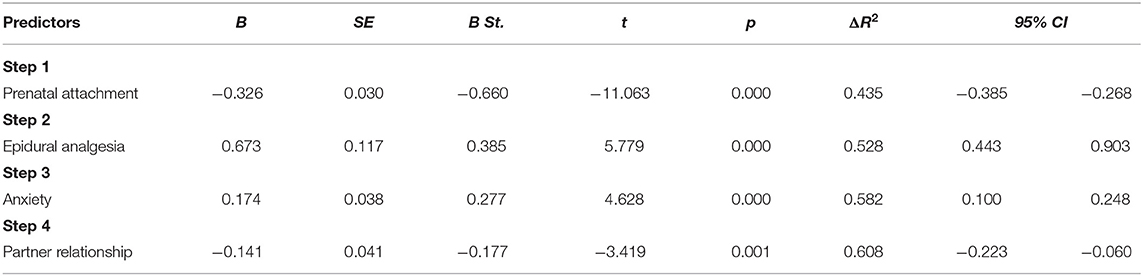

Finally, a multiple regression was conducted to explore which of the significant risk factors found in the previously reported analyses make meaningful contributions to the overall prediction of the severity of PPD, which are: age, anxiety, depression, parental relationship, romantic relationship, prenatal attachment, typology of delivery, and epidural analgesia. All these predictors were entered at the first step, using a stepwise method.

Results showed that the model is composed of only four variables, which explain 61% of the PPD total score variance. Specifically, prenatal attachment to child entered into the equation in Step 1, which accounted for the greatest portion of the variance in PPD scores. The duration of the administration of epidural analgesia entered in Step 2, which contributed an additional 10% of variance. The anxiety score entered in Step 3, which contributed an additional 6%. Finally, the quality of romantic relationships entered in Step 4, which contributed an additional 3%. In Table 5 , all statistical results are reported.

Table 5 . Summary of the linear regression analysis using stepwise method with all risk significant factors as independent variables for PPD score.

Pregnancy and the postpartum period is a delicate moment in a woman's life, characterized by biological, psychological and social change, during which women are at increased risk of emotional vulnerability and depressive symptomatology ( 1 ). This is especially true for nulliparous women, who, in addition to the normal psychic, psychological and relational changes typical of the pregnancy period, are dealing with more specific challenges, such as the transition to motherhood, or the reorganization of mental self-representation. At the first pregnancy, all these changes and reorganizations can represent challenges which are particularly relevant for women, and the presence of problems that prevent them from reaching a good transition to motherhood puts them at greater risk of developing a subsequent depressive symptomology. According to literature, primiparous mothers present an enhanced risk for depression in the postpartum period ( 17 , 18 ) and more severe effects of depression in early interactions with their infants ( 22 ), due to their inexperience compared to multiparous mothers.

In literature, several factors have been found related to PPD, and we believe that the complex interplay of these can be the cause of greater vulnerability in nulliparous women ( 27 – 29 ). For this reason, the main purpose of this study was to explore the role that several sets of variables, such as socio-demographic, individual, relational, and related to delivery characteristics, separately considered, play as risk factors for the onset of postpartum depression in nulliparas. However, to date, no studies have jointly analyzed all these different risk factors. Consequently, the main and second purpose was to verify which have a more significant influence when they are considered together, in order to identify the more important risk factors.

Overall, our results show that, in reference to socio-demographic characteristics, only the age of women was a significant predictor of PPD scores. Older women seem have a higher probability of developing a depressive symptomatology 1 month after childbirth. On the contrary, in line with Roomruangwong's results ( 29 ), we found no significant influences of the level of education, employment status, the length of the romantic relationship, or planned pregnancy.

In reference to psychopathological characteristics, our results showed a strong association between prenatal psychopathology and the possibility to develop PPD. According to previous studies ( 28 , 29 , 53 ), nulliparous with a high level of anxiety and depression during pregnancy tend to develop PPD symptomatology more than women with a low level of these characteristics before delivery. Not surprisingly, due to the high association between antenatal and post-partum depression, the last edition of the DSM ( 9 ) proposed the term “peripartum onset” to indicate the depressive episode occurring during the pregnancy and the first 4 weeks after delivery.

Regarding the relational variables, our results indicated that only the prenatal attachment to child and the quality of romantic relationship affect the level of PPD ( 30 , 32 ). In particular, prenatal attachment, defined as the emotional bond experienced by the parent toward the infant ( 54 ), seems to play a very important role in PPD, given that it involves the maternal disposition toward fetus and a protection attitude toward baby ( 55 , 56 ). New research has suggested that this type of attachment is an indicator of the caregiving system ( 56 , 57 ).