- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 25 November 2019

The authentic balut: history, culture, and economy of a Philippine food icon

- Maria Carinnes P. Alejandria ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5867-4970 1 ,

- Tisha Isabelle M. De Vergara 1 &

- Karla Patricia M. Colmenar 2

Journal of Ethnic Foods volume 6 , Article number: 16 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

138k Accesses

6 Citations

75 Altmetric

Metrics details

The practice of making and eating fertilized duck eggs is a widely known practice in Asia. In the Philippines, “balut” is a popularly known Filipino delicacy which is made by incubating duck eggs for about 18 days. However, criticisms against its authenticity and the unstable demand for balut in the market pose challenges to the development of the Philippine balut industry. Consequently, this research aims to trace the history of balut production and consumption in the Philippines by specifically looking into the following. First, it explores the factors that contribute to the discovery and patronage of balut. Second, it identifies the localities that popularized the balut industry. Third, this includes the key industries that started the large scale production of balut. Fourth, it discusses the local ways of balut-making practices in the country. Lastly, it also provides an account of the ways of balut consumption. Through content analysis of secondary data, this research argues that balut remains an authentic Filipino food despite shared patronage in several Asian countries through the localized meanings associated with its consumption, preparation, and distribution.

Introduction

Balut is a popularly known Filipino delicacy made from incubated duck eggs. It is the main product of the duck industry in the Philippines [ 1 , 2 ] followed by salted duck eggs locally known as “itlog na maalat” [ 3 ]. Its name was derived from the traditional way it was prepared—“balut” which plainly means “wrapped” or covered inside bags during its incubation process. The perfect balut is incubated for 17 to 18 days while its embryo is still wrapped with a whitish covering and has not yet fully developed [ 4 , 5 ]. This is locally known as “balut sa puti” which literally means “wrapped in white.”

Despite the popular association of the consumption of fertilized duck eggs or incubated eggs to the Filipino cuisine, it has been documented to have existed and continuously patronized in many Asian countries. It has been identified that fertilized duck egg consumption was originally developed in China to extend the shelf life of the eggs before the discovery of refrigerators [ 6 ]. It was called “maodan” or literally translated as “feathered” or “hairy egg,” as feathers are still visible when it is cooked. In Vietnam, a similar food preparation is called as hot vit lon , while it is famous as phog tea khon in Cambodia. The main point of differentiation among these duck egg products is the length of the incubation process. The Vietnamese prefer the egg to be incubated for 19 to 21 days so that the embryo will be firm when cooked [ 5 ]. Similarly, it is incubated for 18 to 20 days in Cambodia. At present, it is still popularly known and commonly consumed in most East and Southeast Asian countries, including Laos and Thailand [ 7 ].

During the sixteenth century, the practice of making incubated eggs was believed to be brought by Chinese traders to the Philippines when they settled along the shorelines of Laguna de Bay [ 8 ]. At that time, a particular town near the area has an abundance of Mallard ducks, locally known as “itik.” Itik or more notably known as Pateros itik are being raised mainly for its eggs. This type of duck is being preferred than meat-type ducks because of the local demand for egg production [ 1 ]. In general, ducks are known to adapt in almost all kinds of environmental conditions and varying feeding practices and have immunity to common bird diseases [ 9 ]. This municipality initiated and popularized the process of making incubated eggs which is now famously known as “balut.” Duck farming has been considered as a significant livelihood in many Asian countries [ 10 ]. In the Philippines, balut is the primary product of the industry. In 2015 and 2017, the total egg-based production of the Duck industry has been estimated to be 42 thousand metric tons and 45 thousand metric tons respectively which signify its constant and increasing demand from consumers in the Philippine Market.

Food has been the focus of study among researchers in describing the socio-cultural landscape of a society. In some works, food is used as a point of discussion of history [ 11 ], policy development [ 12 ], and even societal hierarchies [ 13 ] and inequalities [ 14 ]. This current work contributes to the growing literature of food studies, as it traces the socio-historical narratives of the Filipino people in relation to the polarizing ethnic food called balut. Accordingly, the main objective of this study is to trace the history of balut making and consumption in the Philippines. In particular, this would be discussed according to five sub-objectives. First, this study aims to identify the factors that contributed to the discovery and patronage of balut by looking into the economic, social, and cultural contexts. Second, this study maps out the localities that popularized the balut industry in the country. Third, this study also intends to specify the key industries that started off the large scale production of balut. Fourth, this work discusses the local processes of making balut and the various ways of its consumption. It is through the latter three objectives by which this paper positions balut as a distinct Filipino food despite its wide distribution and patronage in Asia.

With these objectives, this study employed a qualitative exploratory design. This study is primarily a scoping review of existing literature on the Philippine duck industry. It also employed content analysis of the secondary data which consisted of historical documents and current literature. Accordingly, this method makes use of existing data to be able to establish what is already known [ 14 ]. This was also used to provide a comprehensive understanding of the balut industry and its development in the Philippines. The data included a variety of sources including journal articles, books, published reports, and news articles. These bodies of literature were assessed and categorized into themes that created the conceptual markers for the documentation of a cultural narrative of balut in the country. The thematic analysis was produced through the usage of qualitative data analysis software with specific use of closed coding and axial coding processes.

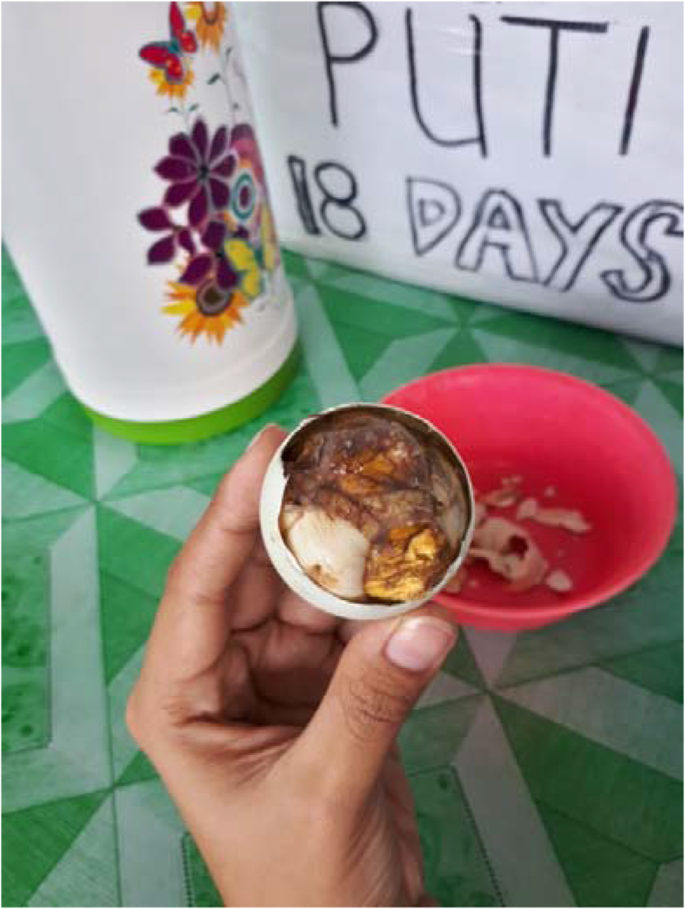

The popularity of balut in most Asian cultures led to the curiosity of Western countries. Foreigners have deemed it as “exotic” and it has been included to the “most disgusting, strange, terrifying food list” [ 15 ]. Consequently, it is characterized as an aphrodisiac or a sexual stimulant [ 16 ] together with other foods that are considered exotic [ 17 ]. Most of the balut’s reputation in other countries are based on the belief that it only serves as an item for doing extreme food challenges and as a proof of masculinity. As a result, it has been a popular snack for men which could be considered as a contributing factor in selling balut at night time. This perspective towards the balut has crossed the mainstream media as several reality television shows, such as Fear Factor and Survivor, which are reputable for showcasing the most extreme and daring challenges, had featured balut eating challenges. In those challenges, contestants had to eat balut under time constraints to be able to advance to the next level. The pained expression on their faces depicts a negative portrayal of balut on national television. This kind of shows presents an exaggerated one-dimensional representation of this delicacy [ 18 ]. Hence, television viewers will immediately assume that such delicacy tastes bad or is unpleasant by purely basing on how the television show presented its physical appearance. When the balut is cracked open, one might find it disgusting to see the embryo forming (see Fig. 1 ). In some instances, the chick may already be showing its beak and is already growing feathers.

Balut sa puti (18 days)

In most Western cultures, balut has also been considered a taboo [ 19 ], specifically because of its high fat content. The growing trend for health consciousness [ 20 ] has categorized balut and other high calorie foods as unacceptable to be eaten. The issue of balut as a taboo has also been evident in some regions in the Philippines. Some ethnic groups like Mankayan Kankana-eys and Kalingas of Tabuk prohibit their pregnant women from eating balut as it may cause some defects to the development of the baby inside the womb [ 15 ]. Such beliefs are rampant and are practiced by people despite the lack of certainty or scientific proof. Meanwhile, it also raises ethical controversies as the egg is eaten while there is an embryo developing inside it [ 21 ]. This tackles an issue of moral consideration—whether it is acceptable or unacceptable to eat an unborn animal. Hence, these concerns likely influence the demand for balut in the market as well as its local consumption.

Despite such criticisms, balut has been hailed as the “national street food” of the Philippines [ 4 ] and was even considered “as popular as hotdogs in the United States” [ 22 ]. It is traditionally being sold by street vendors during the night time until early dawn. Vendors usually carry a basket where the eggs are carefully placed inside and covered with a cloth. It is also filled with some sand to retain its warmth until consumed. Accordingly, they are commonly seen on the corner of the streets, stalls, local markets, bus terminals, restaurants, along the pavement in front of disco bars, and other late night establishments [ 4 , 8 ]. Vendors may be walking, sitting, or cycling while shouting “Balut!” throughout the neighborhood. Balut are also sold by placing them on a makeshift packaging crafted from recycled newspaper or telephone directory. This also contains a small packet of salt and vinegar that is known to enrich the taste of balut.

The attribution of balut consumption to the members of the lower economic strata of society is related to the discovery of eating uncommon foods, like balut, rooted in extreme hunger [ 23 ] and lack of proper food during World War II. Filipinos during that time likely stumbled upon eating duck eggs because of the lack of “decent” food choices present [ 24 ]. Later on, it became popular as an affordable and nutritious snack [ 25 ] that was made available and accessible to all Filipinos. It has been viewed as a good alternative source of high amounts of protein and other nutrients. Balut ranks second to “isaw” or pig/chicken intestines among the most products sold along the streets [ 26 ]. Thus, it has been characterized as a mass-based snack.

During the 1990s, a significant shift from this trend occurred through the introduction of commercial duck feeds. Along with the profitability of this business, the availability of commercial duck feeds encouraged the expansion of small-scale duck farmers into large-scale producers as well as the increase of new commercial operators. Traditionally, duck farms establish their businesses near rivers and lakes since it provides natural food sources for ducks such as snails and shells [ 8 ]. With the introduction of commercial duck feeds, duck farmers who are geographically far from fresh bodies of water were also able to start and maintain their own farm businesses. Subsequently, this expanded the balut industry to other provinces. In 2018, the number of commercial duck farms had an increase of 5.59%, while backyard farms only went up by 2.89% [ 27 ]. Consequently, the duck farming in the Philippines may be classified into two types: small-scale or backyard and commercial. Its main point of comparison depends on the number of duck heads regardless of its breed. It is considered as commercial when the farm has more than 100 heads of duck unless otherwise. The duck industry in the country has also long been dominated by small-scale producers. It was estimated that about three quarters of duck egg producers are small-scale who are mainly found in rural areas [ 1 ].

The increasing demand for balut production has resulted in an increase of duck farms in the Philippines. Thus, duck farming is considered as one of the most profitable livestock industries as well as one of the major sources of livelihood among Filipinos similar to most Asian countries. In general, the Philippines dominates the duck egg production in the global market [ 3 , 28 ]. Duck farming is characterized as inexpensive and requires non-elaborate housing facilities and less space per duck head for rearing [ 29 ]. Hence, it could easily be established in a small land area or even within the backyard. As such, this industry can play a key role in alleviating poverty. The natural abundance of ducks combined with its low-cost maintenance allows even low-income communities to start up their own businesses. It provides employment and income-earning opportunities for marginal communities and rural areas [ 10 , 19 ].

Duck farming ranks second to the broiler chicken industry in the country in terms of egg production [ 10 ]. One of the reasons that the broiler industry became more advanced is primarily due to its increasing commercialization brought about by its massive demand worldwide. In 2002, about 2.69% of the total income of the Philippine agricultural sector comes from the broiler industry while duck farming contributes only about 0.43 percent [ 29 ]. Nonetheless, duck farming continues to thrive mainly because of its profitability and the growing demand for duck egg products and meat. It has been found out that duck farming is more profitable compared to chicken as it requires minimal costs and returns high profit.

As the duck farming industry increases, there is also a direct increase in duck egg production. It was estimated that about a total of 40 thousand metric tons of eggs is being produced annually [ 24 ]. In 2017, the total production of duck eggs accumulated to about 486 million pesos, having a 6.34% increase from 2016 [ 30 ]. This makes up about 1.56% of the total income of the poultry industry of the country. Although this is still a small portion of the poultry industry, the growing demand for balut has resulted in an increase in the number of duck farms and egg producers in the Philippines. About 80% of the total duck egg production is being processed for balut making [ 1 , 25 ], while the remaining 20% was allotted for the selling of raw duck eggs, penoy, and salted eggs.

Aside from raising ducks as a poultry industry, it is also now being promoted for the improvement of the agricultural sector. The integrated rice-duck farming system (IRDFS) has recently been implemented in the Philippines to increase rice productivity. This method was originally developed in Japan and has long been used in many agricultural areas in other countries. In this system, ducks were simply placed in the rice fields where they freely roam around. Additionally, the paddling movement of the ducks will serve as the “labor” in nurturing the soil. In rice fields, weeds and snails are considered as pests for growing rice. The use of ducks will serve as the “pesticide” because these are some of the natural food source of ducks. Accordingly, this eliminates the need for synthetic fertilizers and chemicals [ 2 ]. Moreover, the use of ducks for rice-growing provides farmers with a supply of duck eggs that they could sell for more income. In some provinces where IRDFS is being practiced, rice productivity increased to 9 tons per hectare from the average of 4.2 tons, yet the cost of production went down by 30% [ 31 ]. The implementation of IRDFS becomes a good option for an environmental, low-cost, and healthier way of growing rice and raising ducks. Furthermore, its growing popularity will further contribute to the increase of duck egg production in the country.

Establishing Balut in the Philippine culture

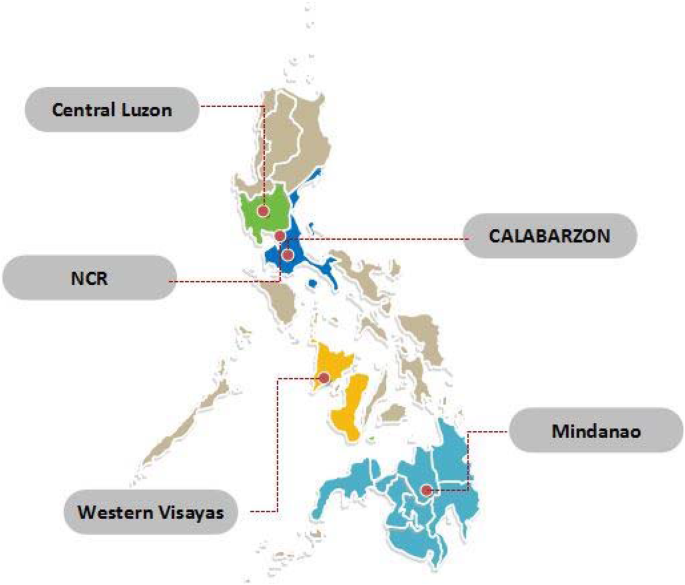

Pateros has been considered the capital of balut industry in the Philippines. It is a small and the only remaining municipality located in Metro Manila along with 16 cities (see Fig. 2 ). It is surrounded by natural bodies of water including Pateros River and Pasig River. In the 1950s, it was estimated that this town has about 400,000 ducks [ 22 ]. Accordingly, duck raising and egg production became a primary source of livelihood for its residents. Primarily, it started out as a cottage industry in this town. Later on, it developed its reputation for producing high-quality duck eggs and became a primary distributor to other provinces throughout the country. Its traditional process of balut making gained much popularity until it became a tourist attraction for Pateros [ 5 ]. The craft of balut making covers about 23% of its local industry at its peak.

Map of the Philippines

In the 1960s, balut from Pateros were characterized with the highest quality. The balut makers were known for their careful selection of eggs. They were also able to develop a localized way of incubating eggs and processing them into products like salted egg and balut. However, massive urbanization and pollution of the Pasig River during the 1970s have led to the decline of duck farming in this area [ 32 ]. The town became uninhabitable for the ducks because their primary source of food was lost as the river became contaminated with harmful substances. As a result, the balut industry in Pateros has slowly been deteriorating since then. Nonetheless, local balut makers who still want to preserve their tradition are still able to continue their businesses by gathering duck eggs from their neighboring provinces, including Bulacan, Laguna, and Nueva Ecija [ 8 ].

In an attempt to revive the balut industry in Pateros, the local government implemented an exemption for duck egg processors from paying the local business tax as well as the annual mayor’s permit fee [ 33 ]. This allowed small-scale balut makers to gain more profit. Pateros also started its own festival called Balut sa Puti Festival to celebrate its own delicacy. This involves a cooking competition featuring balut as a main ingredient for a variety of dishes. Locals of Pateros still believe that their traditional process of balut making is what distinguishes the quality of their balut from other producers which keeps the industry alive.

The slow decline of balut industry in Pateros resulted in a sudden increase in the province of Laguna, particularly in the municipalities alongside Laguna de Bay. The province is located on the south of Manila in the island of Luzon (see Fig. 2 ). Many duck raisers from Pateros have migrated to this area in the hopes of recovering their businesses. One of the main reasons that duck farming is thriving in this area is because of the abundance of snails and shells [ 1 , 8 ]. The large-scale duck egg producers in this province are located mostly in the municipalities of Los Baños, Bay, and Victoria [ 3 ]. The town of Victoria which is located near the shoreline of Laguna de Bay is considered as the largest duck farming industry in the country. It has about 55,000 mallard ducks that hatch about the same number of eggs at a time. Like Pateros, this town also celebrates its own Itik Festival during the second week of November.

Aside from large-scale balut facilities of Laguna, it also has its own rice-duck zones in some of its towns including Sta. Cruz, Siniloan, and San Pablo. One characteristic of the duck and duck egg industry in the province of Laguna is its varying duck-feeding practices. With the abundance of natural food sources, like snails and the availability of commercial feeds, duck raisers are able to utilize both. In the town of Los Baños, farmers feed their ducks with snails every morning, while commercial duck feeds mixed with desiccated coconut in the afternoon [ 3 ]. Accordingly, the feeds are considered as a key determinant in egg production. These aquatic foods are considered as better and more natural feeds compared to the commercial ones because they help improve the quality of the duck eggs.

Central Luzon

The continuous increase of large-scale commercial duck farmers encourages the duck farming in other regions in the Philippines. From Region IV-A, where Laguna is located, the concentration of duck egg production gradually transferred to Region III (see Fig. 2 ) [ 1 ]. As of 2016, the Central Luzon is considered as the topmost duck egg-producing region in the Philippines [ 24 ] and has about an estimated 2.29 million commercial duck production. As regards to the total number of commercial duck farms in the country, two of its provinces, namely Bulacan and Pampanga, represent 28.4% and 25.7% respectively [ 25 ]. It also has the biggest duck population for commercial farms in the country. In some provinces in Central Luzon, particularly in Nueva Ecija and Pampanga, duck farms were comparatively larger in size than those in Iloilo and Quezon [ 29 ].

Western Visayas

The top duck egg-producing regions in the Philippines are Central Luzon and Western Visayas followed by SOCCSKSARGEN, Cagayan Valley, and Ilocos region [ 24 ]. Western Visayas is a region located in the island of Visayas (see Fig. 2 ). In relation to this, Western Visayas has about 1.36 million backyard ducks which is the largest number of small-scale farms in the country. The increasing accessibility of commercial duck feeds has allowed the continuous expansion of duck raising and balut making in other regions.

Aside from balut making in the islands of Luzon and Visayas, evidences of a thriving duck industry in the island of Mindanao has also been observed (see Fig. 2 ). The high demand for duck eggs for balut making had resulted in a significant increase of production, particularly in Cagayan Valley and Zamboanga Peninsula [ 24 ]. In addition, the number of duck egg grower noticeably increased, particularly in the region of SOCCSKSARGEN. By 2018, Central Luzon still tops the list followed by SOCCKSARGEN and Northern Mindanao [ 34 ]. A contributing factor to this may be the implementation of IRDFS in this region since it has a massive agricultural area.

The continuous growth of the balut industry in different parts of the Philippines evidently shows that it has long been established in the history and culture of Filipinos. The craft of balut making may be known as an influence brought by Chinese traders, but nevertheless, Filipinos were able to localize it and develop their own way of balut making and consumption.

The political economy of the balut industry: localities that popularized balut

Small-scale producers are expanding into large-scale facilities to meet the market demands for balut. However, not all are able to establish their own facilities. This caused large egg-processing facilities to purchase their eggs from small duck farms. As such, several balut makers started the large-scale production of balut in the Philippines.

In the town of Pateros, a local named Rufino Capco owns the R&M Balut Industry. Accordingly, this business started during the 1960s and has been operating since then [ 35 ]. While most balut makers in his town already left the industry, Capco still maintained his own business. From Region 3 or Central Luzon, Nanding de Jesus is a famous balut maker in the town of Sta. Maria, Bulacan. He started his business in 1979 with only PhP5600 as his capital. Initially, he placed his balut incubator or balutan inside his own house since he has no sufficient amount of money to establish a larger facility. By 1990, he was able to use his own commercial incubators that houses about 1.5 million duck eggs within a period [ 36 ]. Accordingly, he is now able to sell more than 60,000 duck eggs on a daily basis. This then supplies egg products to most of its neighboring provinces. As the first one to enter the balut industry in his town, he also encouraged his neighbors to try balut making until there were about 28 balut makers. Later on, de Jesus and his neighbors were also able to establish their own balut producers’ association.

The Jashacarl Balut and General Merchandise is also as a known large-scale commercial balut producer that started in 1993 [ 37 ]. This particular balut maker is a bit different from others as it is a combination of duck raiser, balutan, trader, and retailer, all in one. Its duck farm has about 30,000 ducks at a time and produces about an average of 20,000 balut eggs per day. It was also able to expand its industry in other places like Cavite, Las Piñas, and Quezon City.

In 1999, Cecilia Salarda was able to expand her own small-scale balut business [ 38 ]. At first, she simply buys about 60 to 100 duck eggs from nearby farms and then processes them into balut by herself. Soon enough, she was able to buy her first modern incubator. Her business continued to grow until she was able to establish her own balut and salted egg factory and employed more than 20 individuals. She then became one of the largest balut and salted egg producer in the province of Negros Occidental. The increasing popularity of balut making in the province is encouraging the industry’s future development. Moreover, it also provides a good source of income for the locals.

In Zamboanga Sibugay, a couple named Calixto and Maricris Huit have a small-scale balutan. Initially, they only had three manually operated incubators. In 2012, they received an assistance grant from the Enterprise Technology Upgrading Program (SETUP) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) [439]. This allowed them to grow their balutan into a large-scale business. From producing about 1000 to 2000 balut per day, they were now able to manufacture about 5000 and deliver egg supplies to other provinces, including Basilan, Dipolog and Cagayan de Oro. Their business became known as Marc’s Balut Processing Facility.

Local processes of balut making

The perfect balut consists of four main parts: embryo, yolk, bato or rock, and the broth which is sometimes also called as the “soup” [ 7 ]. In buying balut, some may choose between those that were incubated for 16 or 18 days. Individuals trying it for the first time may opt for a 16-day-old balut since the embryo is less developed and the bones and beak are much softer to chew. Still, the 18-day old balut is considered as the best balut known as “balut na puti.” This is also colloquially called “higop” which actually refers to the act of slurping all of its contents. In some cases, balut vendors located near bus terminals are intentionally selling mostly 19-day-old balut since they know that it would be unlikely to see their customers again.

Locally known, there are two kinds of balut that are being produced and sold. The mamatong refers to the type of balut wherein the embryo is floating above the yolk and the white. The other one is called as “balut na puti” or wrapped in white literally because the embryo looks like it is covered with a whitish part when sold. This is made by allowing the eggs to incubate for about 18 days. It is considered as the favorite and perfect kind of balut for Filipinos since the embryo has not fully developed its beak and has no feathers. In distinguishing the two, there is a local belief that the two types of balut may be differentiated by putting them on water. When it floats, it is a mamatong, while it is a balut na puti when it sinks to the bottom.

Traditionally, lakes and rivers serve as the sources of aquatic foods for the ducks such as snails and shells. These aquatic foods are recognized as better feeds than commercial ones as they help improve the quality of the duck eggs [ 3 ]. Meanwhile, the increase of large-scale producers that make about a thousand balut per day does not undergo the same tedious process. Hence, balut makers claim that it does not produce eggs of the same quality.

The preference for duck eggs over chicken eggs is mainly because the former has a stronger shell and shell membrane [ 5 ]. Additionally, duck eggs have a smoother shell texture than the latter. When choosing the type of eggs to be processed, balut makers prefer thick-shelled eggs than thin-shelled ones. Using the “pitik” system, balut makers tap eggs using their fingers to determine which eggs have cracks or are thin-shelled [ 5 ]. Eggs with cracks will give off an empty sound, while thin-shelled eggs produce a brittle sound. On the other hand, thick-shelled eggs are preferred because this type of egg is known to be capable of enduring the tedious process of incubation.

For the incubation, the process must start before the duck egg reaches 5 days old. To begin with, the fertilized duck eggs are placed under the sun for about 2 to 7 h to provide warmth for the eggs [ 18 ]. This is done to remove any moisture left on the eggs before they are placed in the balutan or the incubator. Then, the eggs are transferred to the baskets, inside the balutan. The traditional balutan is an improvised shelter that is usually made from bamboo and nipa palm. Most importantly, it must always be kept dark and humid inside the balutan for proper incubation to take place.

In the incubation, the eggs are being kept in the bamboo incubators that are in the shape of barrels with a normal size of three feet and two feet in width [ 7 ]. Each incubator is made to hold ten bamboo baskets that can be filled with 100 to 120 eggs each. An estimate of about 6000 duck eggs are incubated in a single period. Inside the bamboo baskets, the eggs are placed inside a tikbo (abaca cloth bags) or wrapped in panyo (sinamay fabric) [ 19 ]. The eggs are carefully wrapped to ensure that they are properly incubated. For constant warmth during the process, several bags of palay or rice husks are positioned in between the baskets [ 7 ]. The husks are heated in copper kettles until it becomes extremely hot before being placed in the balutan. In Pateros, rice husks are commonly mixed with mud for the incubation.

During the incubation, the most important part is to turn and reposition each egg for two to three times a day to ensure its consistent growth [ 39 ]. This would also prevent too much heat in a particular side of the egg which may cause it to spoil. Accordingly, the eggs must also be placed according to their age. The more mature eggs which are almost 18 days old are placed at the topmost portion, while the less developed ones, which are usually about 5 days old, are at the bottom of the baskets [ 18 ]. The advancements in the duck and duck egg industry involve innovations in the process of incubation. Local balut makers utilize mechanical incubators to have a more efficient and convenient production of balut (see Fig. 3 ). Similar to the traditional process, the duck eggs still need to be turned from each side so that each egg is able to receive equal amount of heat. Such incubators are powered by electricity to ensure constant source of heat during the process.

Mechanical incubator in a duck farm and balut making facility in Laguna

In identifying whether a duck egg could be sold as a balut or penoy, balut makers utilize the process of candling. The eggs will be shortly removed from the incubation and will be put back when it passes the inspection of a balut maker or magbabalut [ 8 ]. At this process, each egg will be held against the hole of a lighted device called silawan during the 11th and 17th day of incubation [ 5 ]. The box-like device can be in the shape of a triangle or a square that has a light bulb inside it (see Fig. 4 ). When it is inserted in the hole, the balut maker can see the contents of the egg as it operates like an x-ray machine. In the 11th day, the balut makers are already able to identify whether the egg may be sold as a balut or not. It will show a spider-like structure and have a dark spot at the center. On the other hand, transparency means that it has not yet developed. It would simply look like a whole yolk which means that the egg is infertile. This will then be sold as penoy which is highly similar with hard-boiled chicken eggs. This occurs when the thin whitish membrane inside the egg was infiltrated with water. The detection of a penoy may be done as early as the seventh day of incubation since some magbabalut does candling at this time.

Candling process of balut

After the incubation process, the eggs should be momentarily air-dried before immersing them in boiling water with salt. This would take about 20 to 30 min before it becomes ready for consumption [ 7 ]. A cooked balut may last for about a month when refrigerated. However, the broth will dry out quickly. After this process, the balut products are then transported for selling in local markets.

Describing the various ways of balut consumption

Street foods are a significant part of the Filipino culture [ 26 ]. This may be attributed to the affordability and accessibility of such foods. Its cleanliness and safety may pose a concern, yet it remains popular in the market. Balut became popular as a ready to eat night time snack especially for those who would need some energizer or energy boost [ 18 ]. It is also believed that balut is eaten during the night to avoid seeing its hideous look. Accordingly, it is used to alleviate fatigue and sharpen one’s focus, especially for those working during graveyard shifts. It was also known as a pulutan or some sort of snack taken during street drinking sessions. Known to be nutritious, some also eat balut with the belief that it would strengthen their knees and contain some medicinal properties.

Traditionally, the consumption of balut was limited by eating it straight from its shell after it was boiled. The eggs are eaten by gently tapping the wider part of it to create a small opening where the consumer could sip the broth. A pinch of salt or vinegar may be put for a more savory taste. After that, the rest of the shell must be cracked open. The yolk and the embryo are then eaten together. It was also described to have an unusual texture. Most prefer not to eat the white part, which is the rock, since it is quite hard to eat. Some claim that eggs processed with a mechanical incubator does not taste as good as eggs incubated with rice since locals believe that the rice husks give balut a sweeter taste [ 7 ].

Although it seems that penoy are “rejects” of balut, local vendors were able to develop a variation of penoy and sell it in the market. Penoy na may sabaw contains a balut-like broth while penoy na tuyo is a lot similar with hard-boiled chicken eggs. When the penoy is starting to spoil, it will give off a strong sulfur smell when exposed to air. This type of egg is called abnoy or a colloquial term for abnormal. Although this seems that the egg has no use, some locals were able to use it as a main ingredient for a delicacy called bibingkang itlog . This is made by cooking the egg into a scrambled egg which is also called as a rotten egg omelet and sold by placing on a piece of banana leaf. Despite its rotten stinky smell, it is known to be delicious [ 40 ]. However, abnoy is rarely available in local markets. When it is past the balut stage, the chick comes to a state of rigor mortis or nearly about to hatch, called ukbo . It is when there is no yolk or white left but the almost-born chick only. After removed from its shell, this will be cooked in adobo style—seasoned with soy sauce and vinegar and then fried as well. These variations of how the duck eggs can be prepared and used show the ingenuity of Filipinos to make use of what they have and to avoid waste.

In Cubao, Quezon City, the process of making fried balut is believed to be where the industry started [ 4 ]. A vendor was unable to sell some of the balut since it has been incubated longer. To avoid economic losses, she decided to take the chick from the shell and roll them in flour before frying. Later on, the flour is replaced with an orange-colored batter. This street food became known as tokneneng . It is sold while placed on little bowls with some vinegar and salt. In another instance, male chicks are mostly discarded as they do not produce eggs. Then, a local decided to fry these day-old chicks wrapped in a similar orange-colored batter. These are usually sold by putting them inside plastic cups. It is commonly known as super chicks or day zero.

At present, balut is starting to gain recognition in the culinary world [ 19 ]. Like salted eggs, it is now being incorporated into several dishes and desserts. Sorpresa de balut or surprise is an appetizer served in restaurants that has balut seasoned with flour then fried or baked in a crust with some olive oil or butter. In addition, it has recently been used as a flavoring of a gelato. Accordingly, this presents a potential to increase the market for balut in the local and global setting.

It has been established that the process of making incubated eggs originated from China. Consequently, balut may be criticized as inauthentic and foreign to the Filipino culture because of the numerous similar preparations available in other countries. It is maodan in China, hot vit lon in Vietnam, and phog tea khon in Cambodia. The long history of influences brought by different cultures including Chinese, American, and Spanish also resulted in significant changes in the Filipino cuisine. Balut, along with other delicacies such as siomai, bistek (beef steak), and lechon has made its way to the diet of Filipinos. Instead of looking at balut as an inauthentic Filipino food, this emphasizes the shared culture of production and consumption of incubated eggs that can be found in several Asian countries.

The definition of authentic Filipino and Asian cuisine has been limited to what is indigenous [ 41 ]. With this definition, it was presumed that balut is not truly Filipino. However, the discovery of balut and its continuous patronage has allowed it to become more Filipino in various ways. Starting from the tedious process of traditional incubation, the magbabalut carefully ensures that each egg receives the proper amount of heat by placing them on makeshift baskets surrounded by bags of heated husks. Then, each egg is examined during the candling process and continuously incubated until it reaches the perfect 18-day incubated balut. The balut is made readily accessible everyday along the streets where the vendor carries them on baskets filled with sand to ensure its warmth until eaten. It is consumed by cracking one end, sipping its broth, and seasoning it with some vinegar or a pinch of salt. This unusual production and consumption of balut represents the creativity of Filipinos to make something similar with other Asian cultures yet uniquely Filipino. Balut gained its popularity as an affordable, nutritious, and ready-to eat snack that makes it a staple and favorite street food among Filipinos. It has long been embedded in the Filipino culture that it became equated with the Filipino identity. In some ways, it gives off the notion that anyone who cannot eat a balut is not considered a true Filipino [ 2 ]. The balut comes with a symbolic value in the construction of the Filipino identity and even a rite of passage for others [ 18 ]. Balut is able to transcend the notion of authentic Filipino food as indigenous and became a delicacy of its own. Its authenticity lies on its own uniqueness and the meaning that has been ascribed to it. Thus, it has been characterized as a cultural icon in the Philippines.

The balut industry of the Philippines has long been established, yet still remains underdeveloped. With inconsistent and low duck egg production and unstable demand in the market, the future of the balut industry is still uncertain. Headed by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST-PCAARRD), the Itik Pinas is an attempt to improve the local balut industry primarily by increasing the duck egg production. In an agricultural country like the Philippines, the vision of improving the status of the balut industry brings with it the hope of alleviating poverty primarily in the rural sector and the recognition of balut as an authentic Filipino food.

Availability of data and materials

Secondary data are from the literature cited in the bibliography. Primary data may be shared by request to the funding agency: Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development of Department of Science and Technology (DOST-PCAARRD).

Hui-Shung, C, Dagaas C. The Philippine duck industry: issues and research needs. University of New England. 2004.

Escobin R, Medialdia T, Caramihan CF. Quality of ‘balut’ (fertilized duck egg) produced in four rice-duck zones of Laguna. Philippine. J Vet Animal Sci. 2009:35.

Atienza, M. Food safety study of duck eggs produced along Laguna Lake Areas, Philippines. J Nutr Food Sci s3. 2015;doi: https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.S3-005 .

Fernandez DG. Balut to barbecue: Philippine street food. Budhi. 2002;2:329–40.

Google Scholar

Sanceda N, Ueda K, Ibenez J, Suzuki E, Kasai M, Hatae K. Some fine aspects boiled and historical fertilized background and of “balut” and ‘penoy’, boiled incubated fertilized and unfertilized duck eggs. J Cookery Sci Japan. 2007;40:231–8.

Arthur JA. A study of the consumer market for duck and quail egg products: the case of Chinese Canadians in Vancouver. British Columbia: The University of British Columbia; 2013.

Magat M. Balut: fertilized duck eggs and their role in Filipino culture. Western Folklore. 2002;61:63–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500289 .

Article Google Scholar

Libay, JL, Fiedler, LA, Bruggers, RL. Feed losses to European tree sparrows (Passer montanus) at duck farms in the Philippines. 1983

Ramil, MM. Ducks provide power to “livestock revolution”. PhilStar Global. https://www.philstar.com/business/agriculture/2002/08/18/172506/ducks-provide-power-145livestock-revolution146;2002 . Retrieved July 3 2018.

Jha B, Krishna B, Asit C. Duck farming: a potential source of livelihood in tribal village. J Animal Health Production. 2017;5:39–43. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.jahp/2017/5.2.39.43 .

Jati I, Radix AP. Local wisdom behind Tumpeng as an icon of Indonesian traditional cuisine. Nutri Food Sci. 2014;44:324–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/NFS-11-2013-0141 .

Spark, A, Dinour, L, Obenchain, J. Nutrition in public health: principles, policies, and practice. Second. CRC Press. 2015

Siniscalchi, V, Counihan, C. Food activism: agency, democracy and economy. 2013

Greenhoot AF, Dowsett CJ. Secondary data analysis: an important tool for addressing developmental questions. J Cognition Development. 2012;13:2–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2012.646613 .

Grey, EJ. Cultural beliefs and practices of ethnic Filipinos: an ethnographic study 2016;3: 739–48.

Calderon, J. 2014. Balut—how to eat that fertilized duck egg of the Philippines. CNN. Retrieved July 7 2018.

Deutsch, J, Murakhver, N. They eat that? A cultural encyclopedia of weird and exotic food from around the world: a cultural encyclopedia of weird and exotic food from around the world. ABC-CLIO, LLC;2012

Matejowsky T. The incredible, edible balut. Food Culture Society. 2013;16:387–404.

Tacio, H. Making balut for food and profit. Agriculture Magazine.2009

Department of Science and Technology, and Department of Science and Technology. Philippines ehealth strategic framework and plan 2014-2020. 2014;8.

Gupta, Sohini Das. 2016. “To bite or not to bite: food that triggers an ethical dilemma.” DNA India. https://www.dnaindia.com/lifestyle/report-to-bite-or-not-to-bite-food-that-triggers-an-ethical-dilemma-2222579 .Retrieved July 20 2018

Maness H. Balut--A Duck-Egg Delicacy. World’s Poultry Sci J. 2007;6(1):10–3. https://doi.org/10.1079/WPS19500005 .

Doeppers, D.F. Feeding Manila in peace and war, 2016;1850-1945.

Philippine Statistics Authority. Duck industry performance report. January-December 2015. 2016

Boquet, Y. Farm production and rural landscapes. Springer Geography.2017

Buted DR, Ylagan AP. Street food preparation practices. Asia Pacific J Educ Arts Sci. 2014;1:53–60.

Philippine Statistics Authority. Duck situation report January to December 2017. 2018.

Adzitey F, Adzitey SP. Duck production: has a potential to reduce poverty among rural households in Asian communities – a review. J. World’s Poult. Res. Journal Homepage. J. World’s Poult. Res. 2011;1:7–10.

Chang HS, Villano R. Technical and socio-economic constraints to duck production in the Philippines: a productivity analysis. Int J Poultry Sci. 2008;7:940–8. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijps.2008.940.948 .

Philippine Statistics Authority. Duck situation report: January-June 2017.” Quezon. 2017

ICCO Cooperation. 2012. “Raising ducks to boost organic rice production.” https://www.icco-cooperation.org/en/projects/raising-ducks-to-boost-organic-rice-production . Retrieved July 6 2018

Gonzales, ER. Asian perspective Philippine experience: piloting a unified model of sustainability, CNE Equation (Cultural, Natural, and Economic Capitalization) in Pateros Metro Manila and its implication to national progress and sustainable development in the Philippines. 2005

Melican, N. R. 2012. “Pateros officials approve tax break for balut makers.” Philippine Daily Inquirer. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/234825/pateros-officials-approve-tax-break-for-balut-makers . Retrieved July 7 2018

Philippine Statistics Authority. 2018b. “Duck situation report October-December 2018.” https://psa.gov.ph/livestock-poultry-iprs/duck/production . Retrieved July 4 2018

Philippine Asian News Today. 2016. “From boom to gloom: Pateros balut industry fights for life.” Philippine Asian News Today. http://www.philippineasiannewstoday.com/entertainment/from-boom-to-gloom-pateros-balut-industry-fights-for-life/ .July 2 2018

Sarian, Z. B. 2018. “To Grow, He Did Not Keep His Balut Business to Himself.” Manila Bulletin. https://newsbits.mb.com.ph/2018/03/11/to-grow-he-did-not-keep-his-balut-business-to-himself/ .

Union Bank. 2018. “Balut king.” https://www.unionbankph.com/corporate-sme/smallbusiness/small-business/success-stories/21-balut-king .

Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation. 2007. “Cecilia Salarda.” https://nwtf.org.ph/cecilia-salarda/ .

DOST-PCARRD. Duck raising. 1991

Polistico, E. Philippine Food, Cooking, & Dining Dictionary. Anvil Publishing. 2017

Zialcita FN. Authentic though not exotic: essays on Filipino identity. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press; 2007.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This project acknowledges the support of the following institutions and individuals: Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development of Department of Science and Technology (DOST-PCAARRD), Research Center for Social Sciences and Education of the University of Santo Tomas (UST-RCCSED), Reynaldo V. Ebora, Synan S. Baguio, Alfredo Ryenel M. Parungao, Prof. Maribel G. Nonato, Prof. Belinda V. de Castro, and Mr. Jeric Albela.

This project acknowledges the funding support of the following institutions and individuals: Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development of Department of Science and Technology (DOST-PCAARRD) and Research Center for Social Sciences and Education of the University of Santo Tomas (UST-RCCSED). These institutions covered for the data collection and processing expenses for the project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Research Center for Social Sciences and Education, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Maria Carinnes P. Alejandria & Tisha Isabelle M. De Vergara

College of Tourism and Hospitality Management, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Karla Patricia M. Colmenar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MCPA designed the project structure (objectives, methods, analytical frame) and co-authored the “Introduction,” “Results,” and “Conclusion” sections. TIMDV co-authored the “Introduction,” “Results,” “Discussion,” and “Conclusion” sections. KPMC co-authored the “Results” and “Discussion” sections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maria Carinnes P. Alejandria .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alejandria, M.C.P., De Vergara, T.I.M. & Colmenar, K.P.M. The authentic balut: history, culture, and economy of a Philippine food icon. J. Ethn. Food 6 , 16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0020-8

Download citation

Received : 27 May 2019

Accepted : 26 September 2019

Published : 25 November 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0020-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Authenticity

- Consumption

- Philippines

Journal of Ethnic Foods

ISSN: 2352-619X

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2022

Breakfast in the Philippines: food and diet quality as analyzed from the 2018 Expanded National Nutrition Survey

- Imelda Angeles-Agdeppa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9132-7399 1 ,

- Ma. Rosel S. Custodio 1 &

- Marvin B. Toledo 1

Nutrition Journal volume 21 , Article number: 52 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

7 Citations

Metrics details

The quality of foods taken during breakfast could contribute in shaping diet quality. This study determined the regularity of breakfast consumption and breakfast quality based on the food, energy and nutrient intakes of Filipinos.

Materials and methods

Data from the 2018 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS) was extracted for analysis. There were 63,655 individuals comprising about 14,013 school-aged children (6–12 years old), 9,082 adolescents (13–18 years old), 32,255 adults (19–59 years old), and 8,305 elderly (60 years old and above). Two-day non-consecutive 24-h food recalls were used to measure food and nutrient intakes. Diet quality was measured using Nutrient-Rich Food Index (NRF) 9.3. The sample was stratified by age group and NRF9.3 tertiles.

Results and findings

Results showed that 96 – 98% Filipinos across age groups were consuming breakfast. Children age 6–12 years have the highest NRF9.3 average score (417), followed by the elderly (347), adolescents (340), and adults (330). These scores were very low in comparison with the maximum possible NRF score which is 900. The essential nutrient intakes of respondents were significantly higher among those with the healthiest breakfast diet (Tertile 3) compared to those with the poorest breakfast diet (Tertile 1). However, participants in the healthiest breakfast diet did not meet 20% of the recommendations for calcium, fiber, vitamin C, and potassium.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study revealed that majority of the population are regular breakfast consumers. However, the breakfast consumed regularly by Filipinos were found to be nutritionally inadequate. And even those classified under Tertile 3 which were assumed as having a better quality of breakfast were still found to have nutrient inadequacies. Thus, the study suggests that Filipinos must consume a healthy breakfast by including nutrient-dense foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fresh meat, and milk to provide at least 20–25% of the daily energy and nutrient intakes.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breakfast is often regarded as the most important meal of the day. The American Heart Association defines breakfast as the first meal of the day eaten within 2 h after waking up [ 1 ]. Latest evidences from previous studies suggest consuming about 15 – 25% of the daily energy intake at breakfast [ 2 ], wherein the composition of the foods consumed should be from the five main food groups such as: Starchy foods, fruits and vegetables, milk and dairy, protein sources and low-fat spreads and oils. Other recommendations from nutrition and dietetics institutes suggest that breakfast consumption is a key component to an optimal diet which improves cognitive function and helps control against weight gain [ 3 , 4 ]. It was also found that a breakfast high in protein and fat proves to aid in the management of glycemic index among type 2 diabetics [ 5 ]. The International Breakfast Research Initiative (IBRI) aimed to develop nutritional guidelines for a healthy breakfast by conducting a standardized study of national nutrition surveys from selected Asian countries [ 6 ].

Throughout the years, a significant amount of literature has supported the beneficial effects of breakfast consumption. Several studies have consistently recorded a broad variance in breakfast’s contribution to nutrient intake and diet quality in different parts of the world [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Daily breakfast intake was correlated with higher intakes of healthier foods such as whole grains, dairy, and vegetables, thus giving breakfast consumers a higher tendency to achieve recommended nutrient intakes [ 10 ]. In adolescents, there is a reduced risk of becoming overweight or obese [ 12 13 ]. In terms of mental health, it was found out that breakfast consumers were less likely to be emotionally distressed, have lower risk of depression and perceived stress compared to its opposite counterpart [ 14 ].

In the Philippines, there is limited information about breakfast consumption.

A typical Filipino diet in a day consists of about three and a half (3 ½) cups of cooked rice, one (1) matchbox of fried fish, and half (1/2) cup of boiled vegetables per day and these are usually consumed during the three (3) major meals of the day: breakfast, lunch and supper []. Previous studies found that breakfast food pattern in the Philippines and specific provinces was rice, bread, fish, egg, and coffee which were mainly composed of foods rich in carbohydrates, protein, and fat [ 16 17 ]. It was noticeable that the regular breakfast of Filipinos was lacking in vitamins and minerals which are commonly found in fruits and vegetables. In a study with 45 severely wasted children, the respondents “always” eat their lunch and dinner at home and “sometimes” only for breakfast and after the school feeding program was implemented, the respondents' nutritional status significantly improved to normal [ 18 ]. Research has pointed out that nutrients that are unattained during breakfast are not compensated by meals in the later day, thus stressing the importance of breakfast consumption in meeting daily nutrient requirement [ 19 ]. The overarching objective of this study determined the regularity of breakfast consumption and breakfast quality based on the food, energy and nutrient intakes of Filipinos.

Methodology

Study population.

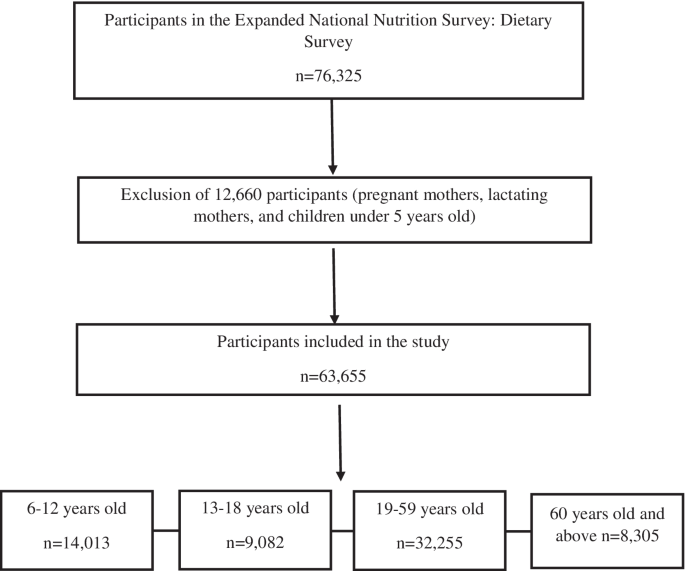

For this study, data was derived from the 2018 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS) dietary component survey. The coverage population of the ENNS is about 40 provinces with over 80,540 surveyed individuals with a response rate of 81.5%. The 2018 ENNS utilized the 2013 Master Sample List developed by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). This sampling design followed a two-stage cluster sampling technique. The first stage involved the selection of Primary Sampling Units (PSUs), which involved sampling domains from 81 provinces, wherein 16 sample replicates was drawn from each domain. The second stage involved the selection of households from the 16 sample replicates. During this stage, the selected households served as the final sampling unit [ 20 ]. The final sample size that is included in this study was n = 63,655. The breakdown per age of the total sample size are as follows: 14,013 school-aged children (6–12 years old), 9,082 Adolescents (13–18 years old), 32,255 Adults (19–59 years old), and 8,305 Elderly (60 years old and above) Fig. 1 .

Flowchart for sample selection. Data from the 2018 ENNS was used with a starting sample size of 76,325. After exclusion of participants and checking of completeness of the data, final participants included in the study is 63,655

Breakfast regularity and dietary data

Breakfast was defined based on the meal code number 1 indicated in the questionnaire which was self-reported as “Breakfast” by the interviewee. On the other hand, breakfast skipping was defined in this study as no breakfast consumption or less than 50 kcals of energy consumed at breakfast otherwise regular consumer if more than or had 50 kcal [ 10 ]. Two day non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls were done face-to-face with each participant or child's parent or caregiver. The interviews were conducted by trained registered dietitians during home visits using a prepared questionnaire. The initial 24 h dietary recall was collected for all respondents, and a second 24 h dietary recall was completed in 50% of randomly selected households only on a non-consecutive day to estimate the day-to-day variation component in energy and nutrient consumption necessary for habitual intake analysis. The second 24 h dietary recall was generally obtained 2 days after the first 24 h recall. Food records were encoded and estimated energy and nutrient intakes were processed using the electronic–based Individual Dietary Evaluation System (IDES) developed by the Institute. This system contains the data of the updated Filipino Food Composition Tables (FCT) [ 21 ].

NRF9.3 scoring of breakfast consumption

Diet quality was measured using the Nutrient Rich Food Index (NRF) 9.3. The NRF9.3 is a validated measurement tool to determine the nutrient density of the total diet. The determination of the nutrient density score for the NRF 9.3 is calculated by the sum of the percentage daily reference values (DRVs) of the nine nutrients that are recommended (protein, dietary fiber, vitamin A, C, and D, calcium, iron, potassium, and magnesium) minus the sum of the percentage of DRVs for the three nutrients to limit (added sugar, saturated fat, and sodium). Total sugar intake was used since added sugar was not included in the survey. The closer the value is to the maximum score of 900 would indicate better quality of the overall diet. The basis for the NRF9.3 algorithm was from a nutrient profiling model on linking food items that have the highest nutrient density at the same time, affordable and engaging [ 20 , 22 , 23 ].

The Philippine Dietary Reference Intake (PDRI) and other standard recommendations were used to calculate the reference daily values (DVs) []. The following were the qualifying nutrients and standard reference amounts: protein (50 g), fiber (25 g), vitamin A (1500 RE), vitamin C (60 mg), vitamin D (10 mcg), calcium (1000 mg), iron (18 mg), potassium (3500 mg) and magnesium (400 mg). The 3 disqualifying nutrients and maximum recommended values (MRVs) were: added sugar (50 g), saturated fat (20 g) and sodium (2400 mg).

The following is the NRF 9.3 calculation formula:

where intake i is the intake of each nutrient, ED is the energy density, and DV i is the reference daily value for that nutrient. In NR calculation, the intake of each nutrient for each subject was normalized for 2000 kcal and expressed as a percentage of the reference DVs. Previously, nutritional % DVs were capped at 100, so that an extremely high intake of one nutrient could not compensate for a dietary deficiency of another. Only the portion in excess of the recommended quantity was taken into account for the LIM.

Commonly consumed food at breakfast

Food group consumption was express as actual intake (in grams) and percentage of consumer. Consumers of each food group were scored 1 if they consumed at least 10 g otherwise 0 (< 10 g) [ 27 ]. Only the top 10 mostly consumed food groups were presented in this study.

Contribution of breakfast to the daily intake and recommendation

The percentage contribution of breakfast to daily nutrient intake was calculated by calculating the total intake of each nutrient at breakfast divided by the total intake of each nutrient at daily intake multiplied by 100. The percentage contribution of breakfast among people with the healthiest breakfast quality to the daily recommendation was calculated by dividing their intake to the recommendation for each nutrient and their respective recommendations and then multiplied by 100. Same calculation was done for the percentage contribution of nutrient intake from all meals to daily recommendation.

Outlier determination

Quality control of the dietary intake data was conducted in two steps. In the first step, the foods reported by a participant like coding information, and quantity were reviewed. In the second step, scatterplots and histograms was used to determine the outliers of the datasets. For implausible micronutrient intake, excessive intakes were defined as those that exceeded 1.5 times of the 99th percentile of the observed intake distribution of the nutrient in the corresponding sex, and age group. Intakes above the upper limit were substituted by a random value generated from a uniform distribution in the intervals with lower bound equal to the 95th percentile of the observed intake and an upper bound equal to 1.5 times the 99th percentile [ 28 ]. After validation and checking for completeness, a total of 12,670 participants were excluded in this study. This included pregnant mothers, lactating mothers, children 5 years old and below, and outliers.2.3. Measurement of Diet Quality.

Statistical analysis

PCSIDE version 1.02 (Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA) was utilized in estimating the usual nutrient intakes at breakfast. This program estimates distributions of usual nutrient intake by removing the effect of day-to-day (intra-person) variability in intake from daily intakes [ 29 , 30 ]. All statistical analyses were performed in the STATA version 15 (StataCorp, USA) software. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the mean difference of NRF 9.3 scores, energy and nutrients intakes between age groups. Differences in food group consumption were tested using Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), adjusted for energy at breakfast as well as sociodemographic characteristics. NRF9.3 score were group into tertiles using –xtile- command in STATA, where, Tertile 1 represent the group with the poorest breakfast quality and Tertile 3 have the healthiest breakfast quality. A trend test was conducted to test whether nutrient intakes at breakfast tends to either increase or decrease across NFR tertiles. Chi-square test was conducted to test the association between consumption of food group and NRF 9.3 Score in tertiles. To achieve estimates at a population level, weighting recommendations was followed in all analyses using “svy” command. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Breakfast regularity across participants’ characteristics

Table 1 shows that 96–98% are breakfast consumers. Only 2% of the younger age groups (6–12 yo and 13–18 yo) were breakfast skippers while for both adults and elderly groups, the percentage slightly increased to 4%. Almost all participants were breakfast consumers across demographic characteristics and nutritional statuses (male 95–98%, female 96–98%). There was a significant association between breakfast consumption and gender among adults only. Proportion of female breakfast consumers (96%) was higher compared to males (95%). In contrast to urban areas, higher percentage of breakfast skippers were significantly observed in rural areas among adolescents (2.3%), adults (4.7%) and elderly (4.8%) groups. It appears that proportions of breakfast consumers across wealth quintile was almost equivalent for all age groups. Educational attainment was significantly associated to breakfast consumption among adults and elderly group. For adults, the proportion of breakfast consumers who have an elementary and college level education was 94% and 97%, respectively. On the other hand, the proportion of breakfast consumers among the elderly with elementary level and college level education was 95% and 98%, respectively. Nutritional status of the children and adolescents was not associated to breakfast status. Elderly with chronic energy deficiency (CED) (94%) has the lowest proportion of breakfast consumers (94%), while overweight (97%) and obese (98%) elderly has the highest proportion of breakfast consumers.

Consumption of commonly consumed food at breakfast by NRF9.3 tertiles

Tables 2 , 3 , 4 and 5 presents the average consumption of the top 10 mostly consumed food groups. The NFR 9.3 tertiles are also shown for the age groups including the percentage consumption of each food group. The analyses showed that consumption of all top 10 food groups were associated to NRF tertiles. The highlight of this result explains that individuals with the Tertile 3 consumed more vegetables, fresh meat and fish, and eggs but less in rice, sugar and coffee.

In Table 2 , children with poorest quality diets (Tertile 1) have a higher percentage consumption of cereal products (51%) and sugars (27%) while having lower consumption of powdered milk (11%), other vegetables (2%), green leafy vegetables (0.4%), fresh fish (2%), chicken eggs (6%), cacao and chocolate-based beverages (1%), and rice (49%). For adolescent group in Table 3 , results show that Tertile 1 has a higher percentage consumption of coffee (57%), sugars (30%), and cereals products (52%) while having the lowest percentage consumption of green leafy vegetables (0.4%), other vegetables (3%), cacao and chocolate-based beverages (0.3%), chicken egg (6%), fresh fish (2%), and rice (43%) compared to T2 and T3. Consumption of coffee seems to increase as age increases with tertile 1 having the highest consumption including sugars. This is evident in the analysis for the adults and elderly group. In Table 4 , results showed that adults aged 19–59 years old in Tertile 1 has the highest percentage consumption of coffee (85%), and cereal products (47%), while having the lowest percentage consumption of green leafy vegetables (0.4%), other vegetables (2%), and chicken egg (7%), fresh fish (2%), fresh meat (1%) and rice (29%) compared to T2 and T3. On the other hand, results shown in Table 5 for the elderly group aged 60 years old and above shows that Tertile 1 has the highest percentage consumption of coffee (88%), and cereal products (48%) while having the lowest percentage consumption of green leafy vegetables (0.4%), other vegetables (2%), powdered milk (3%), chicken egg (8%), fresh fish (3%), and rice (29%) compared to T2 and T3. For all age groups, Tertile 3 has the highest mean consumption of fresh fish, green leafy vegetables and other vegetables while having a moderate consumption of rice, chicken egg, and cooking oil. Younger age groups such as school age children and adolescents who belong to T3 had the highest consumption of chocolate-based beverages. While older adults and elderly in T3 had the highest consumption of rice and the least consumption of coffee.

Usual energy and nutrient intakes at breakfast and NRF9.3 scores by age group

Table 6 presents the average NRF 9.3 scores and mean habitual intake of energy and nutrients at breakfast per age group. Children age 6–12 years has the highest NRF 9.3 average score with 417 which reflects to a healthier diet at breakfast compared to elderly with 347, adolescent (340) and also for adult (330) age groups which had the lowest scores. In all the age groups, breakfast contributed approximately 328 kcal to 440 kcal of their daily intake with the significant highest mean intakes of energy among adolescents (440 kcal) and adults (426 kcal). In terms of macronutrients, the highest mean intakes for total carbohydrates at breakfast were significantly observed among adults (77 g) followed by adolescents (77 g), elderly (64 g) and lastly, school-aged children (54 g). Mean protein intakes were also considerably highest in adolescents (13 g) and lowest in children (10 g). This similar trend is also observed with other nutrients such as fiber, niacin, vitamin D, magnesium, and potassium. With regards to total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat (MUFA), polyunsaturated fat (PUFA), cholesterol, sodium, and iron, mean intakes were significantly highest among adolescents and lowest in the elderly. Highest mean intakes of total sugar and calcium were seen among the elderly while vitamin A intake was significantly higher among adults.

Usual energy and nutrient intakes at breakfast by NRF9.3 tertiles

Tables 7 , 8 , 9 and 10 showed the mean intake of usual energy and nutrients across NRF9.3 tertiles. In Table 7 , results showed cumulative trend of energy intake at breakfast across NRF9.3 tertiles. There was a significant trend in all nutrients across NRF9.3 tertiles at breakfast among children except for total fat and saturated fat. Also, increasing consumption were observed across NRF9.3 tertiles for energy, protein, carbohydrates, fiber, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, iron, magnesium, potassium, and cholesterol, while a decreasing trend was seen for MUFA, PUFA, total sugar and sodium intake. In Table 8 , consumption of all nutrients among adolescents showed significant trends including energy intake. Moreover, consumption of total fat, saturated fat, MUFA, PUFA, total sugar and sodium declined across NFR tertiles while other nutrients significantly increased. For adults and elderly groups in Tables 9 and 10 , both groups had the same results which was all nutrients including energy intake showed significant increasing trends across NRF tertiles. Total sugar and sodium intake decreases from tertile 1 to tertile 3. Results emphasize that the consumption of the population group in Tertile 3 consumed more essential nutrients such as vitamins and minerals and less intake of sodium, total sugar and total fat.

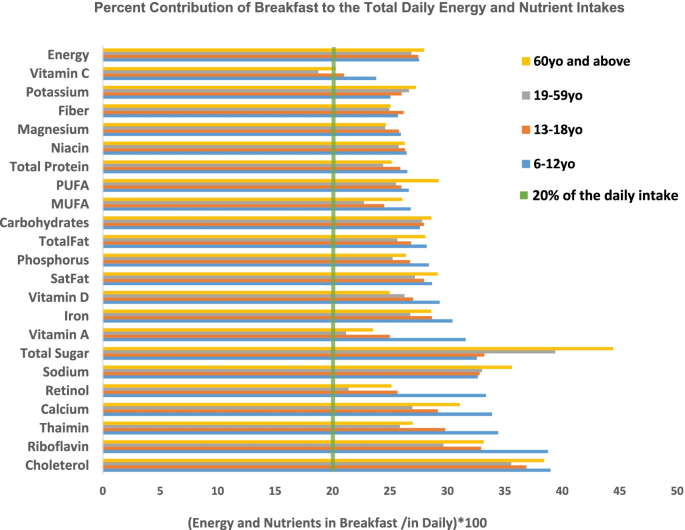

Contribution of energy and nutrients at breakfast to the total daily intake

Figure 2 shows the energy and nutrient contribution of breakfast to the total daily intake. Breakfast must consist at least 20–25% of the total daily energy and nutrients. Overall, energy and nutrients coming from breakfast reached more than the 20% of the total daily intake of energy and nutrients. On the other hand, total sugar, cholesterol, and sodium contributed to more than 30% at breakfast for all age groups. Total sugar accounted for 40% of daily consumption at breakfast for adults aged 19–49 years old and goes up to approximately 45% for the elderly. Contribution of vitamin C at breakfast seems to be low especially for adults aged 19–59 years old which means that vitamin C intake was low during breakfast.

Energy and nutrient contribution of breakfast to the total daily intake. *PUFA stands for polyunsaturated fatty acids, MUFA stands for Monounsaturated fatty acids, SatFat stands for saturated fatty acids. The 20% cutoff is indicated by a vertical line with color green bar

Contribution of breakfast to the daily recommended intakes

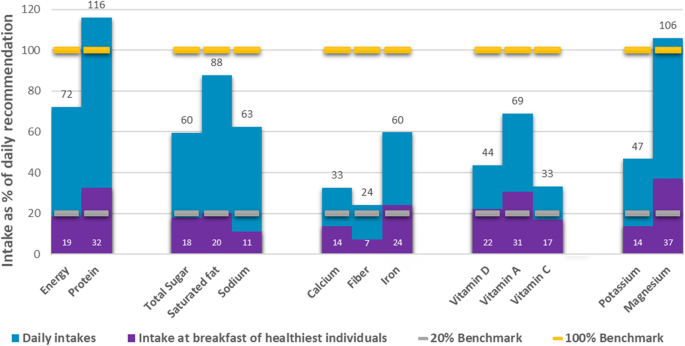

Figure 3 showed that children with the healthiest breakfast diets met the 20% recommendation for intake of protein (32%), iron (24%), vitamin D (22%), vitamin A (31%) and magnesium (37%) but fall short in energy (19%), calcium (14%), fiber (7%), vitamin C (17%) and potassium (14%) intakes at breakfast. On a daily basis, intake of magnesium and protein were more than adequate but there were deficiencies in calcium, fiber, iron, vitamin D, vitamin C, and potassium. There were no recorded excessive intakes of total sugar, saturated fat, and sodium intake at breakfast, same was observed in the results for daily consumption. Results also showed that there is a low nutrient consumption at breakfast.

Contribution of breakfast to the daily recommendation among children NOTE: Daily Intake = All meals; Intake at breakfast of healthiest individuals = intake from breakfast only of participants that were categorized in Tertile 3 which represent the individual with healthiest diet; 20% Benchmark = 20% of the recommended intake of each nutrient (based on the PDRI), 100% Benchmark = the total recommendation per day

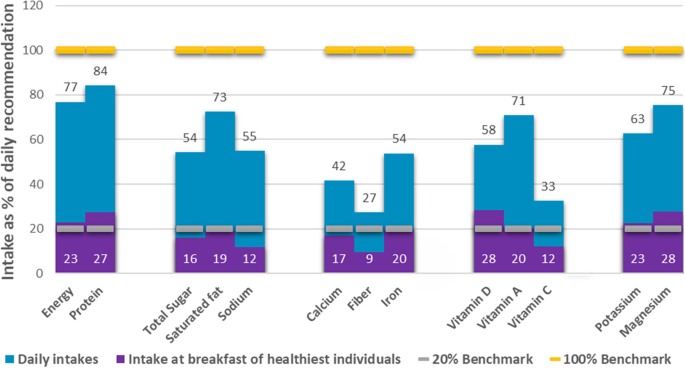

Adolescents with the healthiest breakfast diets met the 20% recommended intake of protein (26%), vitamin D (29%), vitamin A (22%) and magnesium (24%). Only 7% of fiber at breakfast was consumed. Poor intakes of calcium (12%), iron (15%), and vitamin C (12%) were observed at breakfast for adolescents. There is a slightly low contribution (11%) of total sugar, saturated fat (17%), and sodium (13%) for this group. Overall, it is noticeable that most micronutrients were inadequate especially calcium, fiber and vitamin C (Fig. 4 ).

Contribution of breakfast to the daily recommendation among adolescent. NOTE: Daily Intake = 24 h food recall (All meals); Intake at breakfast of healthiest individuals = intake from breakfast only of participants that were categorized in Tertile 3 which represent the individual with healthiest diet; 20% Benchmark = 20% of the recommended intake of each nutrient (based on the PDRI), 100% Benchmark = the total recommendation per day

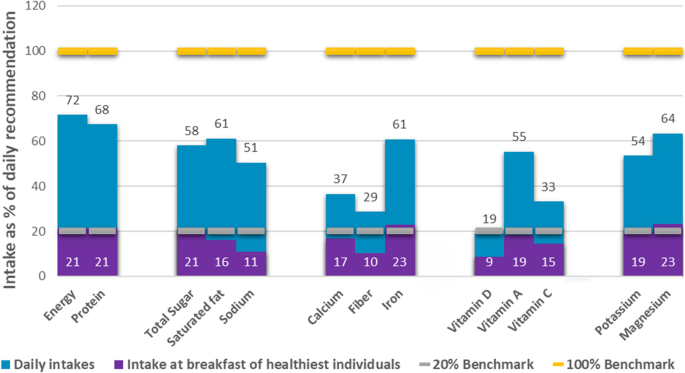

Adults with the healthiest breakfast diets (Tertile 3) were adequate in energy (23%), protein (27%), iron (20%), vitamin D (28%), vitamin A (20%), potassium (23%) and magnesium (28%) at breakfast. However, contribution of calcium (17%), vitamin C (12%), and fiber (9%) at breakfast is low, which is an unceasing problem up until this age group (Fig. 5 ).

Contribution of breakfast to the daily recommendation among adults. NOTE: Daily Intake = 24 h food recall (All meals); Intake at breakfast of healthiest individuals = intake from breakfast only of participants that were categorized in Tertile 3 which represent the individual with healthiest diet; 20% Benchmark = 20% of the recommended intake of each nutrient (based on the PDRI), 100% Benchmark = the total recommendation per day

Among the elderly with the healthiest breakfast diets, their breakfast consumption reached more than the 20% recommended intake of energy (21%), protein (21%), iron (23%), and magnesium (23%). However, the composition of their breakfast was inadequate in fiber (10%), vitamin D (9%), vitamin C (15%), and calcium (17%). There was only 1% excessiveness of total sugar (21%), and no excessiveness of saturated fat and sodium. On a daily basis, they were inadequate of calcium, fiber, vitamin D, and vitamin C (Fig. 6 ).

Contribution of breakfast to the daily recommendation among elderly. NOTE: Daily Intake = 24 h food recall (All meals); Intake at breakfast of healthiest individuals = intake from breakfast only of participants that were categorized in Tertile 3 which represent the individual with healthiest diet; 20% Benchmark = 20% of the recommended intake of each nutrient (based on the PDRI), 100% Benchmark = the total recommendation per day

The present study determined the regularity of breakfast consumption and its contribution to the daily energy and nutrient intakes of Filipinos in order to serve as basis for breakfast recommendations in the Philippines. To our knowledge, the present study was probably the first attempting to describe the breakfast consumption of Filipinos. With the use of the secondary data from the 2018 ENNS gathered by the DOST-FNRI, this study was able to analyze the breakfast intakes of Filipinos [ 21 ]. Although the initial objective of the IBRI consortium was to pull together breakfast studies in Southeast Asia to come up with a prevailing unified recommendation for the region, this has been proven a challenge because of the varied breakfast definitions across countries, the different meal occasions, and the variety of food groups consumed at breakfast. Hence, the breakfast profile of Filipinos remained as the immediate topic of investigation in this study.

Breakfast regularity

Results from the analysis reported that majority of the Filipino population (96-98%) regularly consume breakfast. This strongly identifies that breakfast is an important meal for Filipinos. As stated in a previous literature, the regularity of breakfast consumption and meal times were closely related to healthy lifestyle habits and could play an important role in providing adequate nutrients [ 31 , 32 , 33 ].

Commonly consumed food and nutrient intakes at breakfast in relation to diet quality

In terms of breakfast energy and nutrient intakes, the present analyses also allowed this study to identify food choices and breakfast patterns that were associated with the highest quality of breakfast diets, as captured by NRF 9.3 scores. Participants were divided into tertiles based on their NRF 9.3 scores for each age group to investigate the associations between breakfast nutrient intake and overall diet quality. The age groups with the highest NRF 9.3 score or Tertile 3 (group with the healthiest breakfast) were characterized in this study to consume higher amounts of essential nutrients and more diversified diets as per food groups consumption, compared to lower tertiles. Moreover, a higher NRF score was associated with a higher consumption of desirable food groups making the index an ideal measurement of overall diet quality.