- Military & Veterans

- Transfer Students

- Education Partnerships

- COVID-19 Info

- 844-PURDUE-G

- Student Login

- Request Info

- Bachelor of Science

- Master of Science

- Associate of Applied Science

- Graduate Certificate

- Master of Business Administration

- ExcelTrack Master of Business Administration

- ExcelTrack Bachelor of Science

- Postbaccalaureate Certificate

- Certificate

- Associate of Applied Science (For Military Students)

- Programs and Courses

- Master of Public Administration

- Doctor of Education

- Postgraduate Certificate

- Bachelor of Science in Psychology

- Master of Health Care Administration

- Master of Health Informatics

- Doctor of Health Science

- Associate of Applied of Science (For Military Students)

- Associate of Science (For Military Students)

- Master of Public Health

- Executive Juris Doctor

- Juris Doctor

- Dual Master's Degrees

- ExcelTrack Master of Science

- Master of Science (DNP Path)

- Bachelor of Science (RN-to-BSN)

- ExcelTrack Bachelor of Science (RN-to-BSN)

- Associate of Science

- Doctor of Nursing Practice

- Master of Professional Studies

The average Purdue Global military student is awarded 54% of the credits needed for an associate's and 45% of the credits needed for a bachelor's.

- General Education Mobile (GEM) Program

- AAS in Health Science

- AS in Health Science

- BS in Organizational Management

- BS in Professional Studies

- AAS in Criminal Justice

- AAS in Small Group Management

- AAS Small Group Management

- Master's Degrees

- Bachelor's Degrees

- Associate's Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Continuous Learning Courses

- Tuition and Financial Aid Overview

- Financial Aid Process

- Financial Aid Awards

- Financial Aid Resources

- Financial Aid Frequently Asked Questions

- Financial Aid Information Guide

- Tuition and Savings

- Aviation Degree Tuition and Fees

- Professional Studies Tuition and Fees

- Single Courses and Micro-Credentials

- Time and Tuition Calculator

- Net Price Calculator

- Military Benefits and Tuition Assistance

- Military Educational Resources

- Military Tuition Reductions

- Military Spouses

- Student Loans

- Student Grants

- Outside Scholarships

- Loan Management

- Financial Literacy Tools

- Academic Calendar

- General Requirements

- Technology Requirements

- Returning Students

- Work and Life Experience Credit

- DREAMers Education Initiative

- Student Identity

- Student Experience

- Online Experience

- Student Life

- Alumni Engagement

- International Students

- Academic Support

- Career Services

- COVID-19 FAQs

- Faculty Highlights

- Student Accessibility Services

- Student Resources

- Transcript Request

- About Purdue Global

- Accreditation

- Approach to Learning

- Career Opportunities

- Diversity Initiatives

- Purdue Global Commitment

- Cybersecurity Center

- Chancellor's Corner

- Purdue Global Moves

- Leadership and Board

- Facts and Statistics

- Researcher Request Intake Form

Most Commonly Searched:

- All Degree Programs

- Communication

- Criminal Justice

- Fire Science

- Health Sciences

- Human Services

- Information Technology

- Legal Studies

- Professional Studies

- Psychology and ABA

- Public Policy

- Military and Veterans

- Tuition and Fee Finder

- Financial Aid FAQs

- Military Benefits and Aid

- Admissions Overview

- Student Experience Overview

- Academic Support Overview

- General Education

10 Strategies to Improve Your Reading Comprehension for College

Some college students struggle with assignments because they lack sufficient reading comprehension skills. According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy , 43% of U.S. adults lacked the basic skills to read and understand college-type and other such dense texts. They also can’t determine cause and effect, make simple inferences, summarize, or recognize an author's purpose.

In high school, some savvy students can get by with doing little reading and relying on class discussions to prepare them for quizzes and tests. It’s not easy to do the same in college—especially if you’re taking classes online. If some reading is assigned, you are expected to do it.

If you are out of practice or your comprehension isn’t up to standard, you can find yourself in trouble. Putting assignments off until the last minute won’t help, either.

One way to make sure you’re getting all you can from your assignments is to brush up on your reading comprehension skills. Here are some active reading strategies and tools you can use to bolster your reading for college.

1. Find Your Reading Corner

The right reading environment should fit with your learning style. The right spot will increase your focus and concentration. Consider four factors:

- Atmosphere: Is there sufficient lighting? Do you have a comfortable chair?

- Distractions: Is there enough quiet? Have you muted or turned off your phone?

- Location: Is this spot convenient to things you need?

- Schedule: Have you given yourself enough time to complete the reading and assignments?

2. Preview the Text

Survey the material and ask some questions before you start reading. What’s the topic? What do you already know? What can you learn from the text from any table of contents, glossary, or introduction? What do titles, subheadings, charts, and graphs tell you?

3. Use Smart Starting Strategies

When you start reading, don’t let the text overwhelm you. Use these strategies to keep your reading assignment under control.

- Break up the reading: If an assignment seems daunting, break it into bite-sized sections.

- Pace yourself: Dense material, such as that in textbooks, can be tough to read. Manage your time well and schedule regular breaks.

- Check for understanding: As you read, occasionally ask yourself if you understand what is being communicated. If not, you may need to go back and reread a paragraph or section.

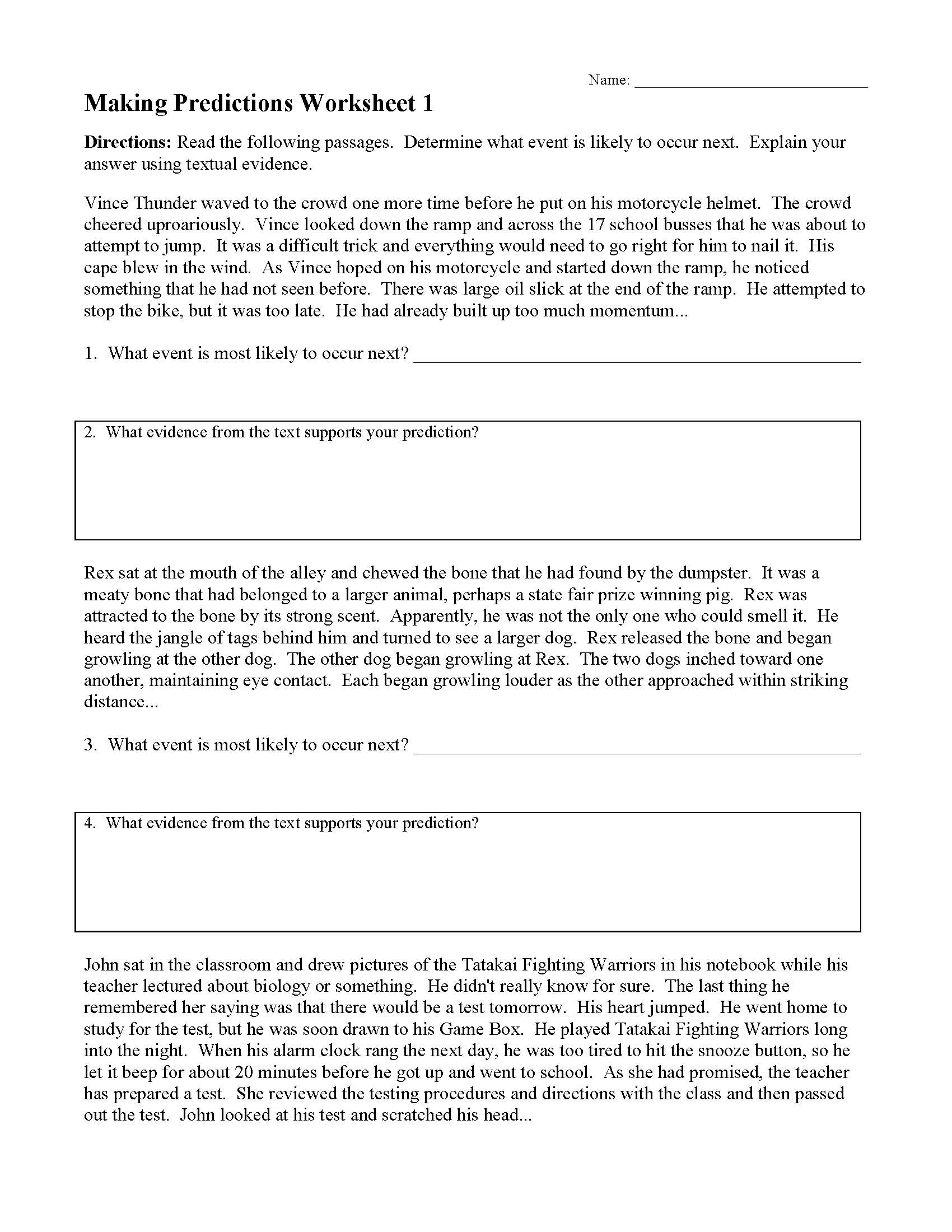

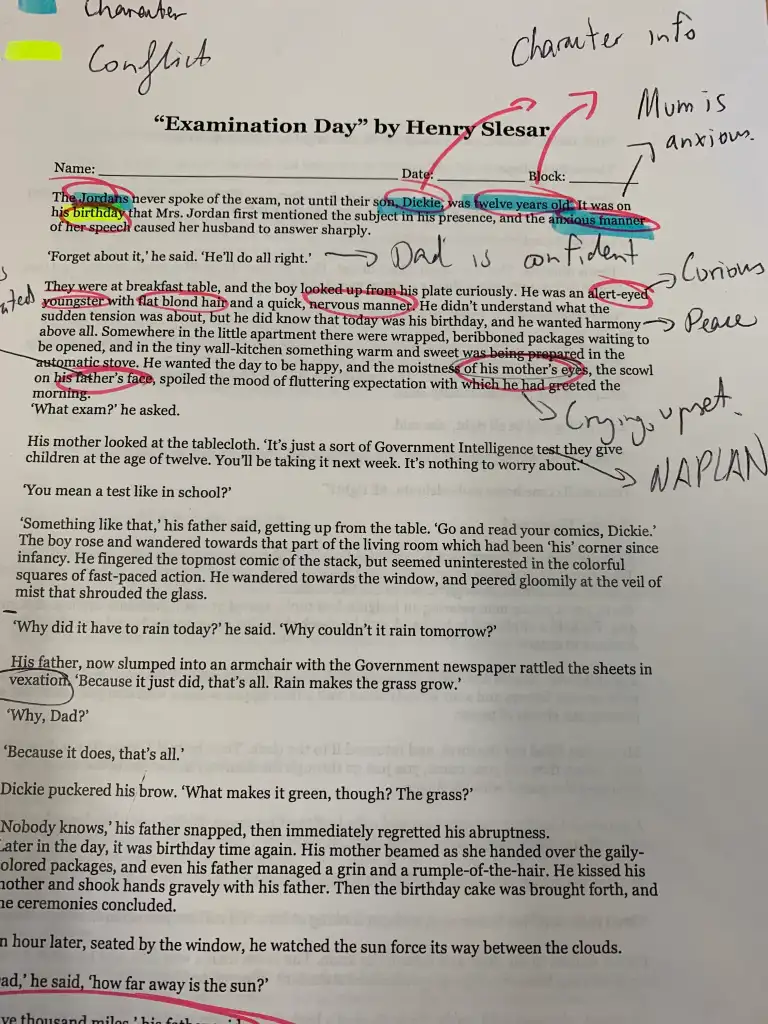

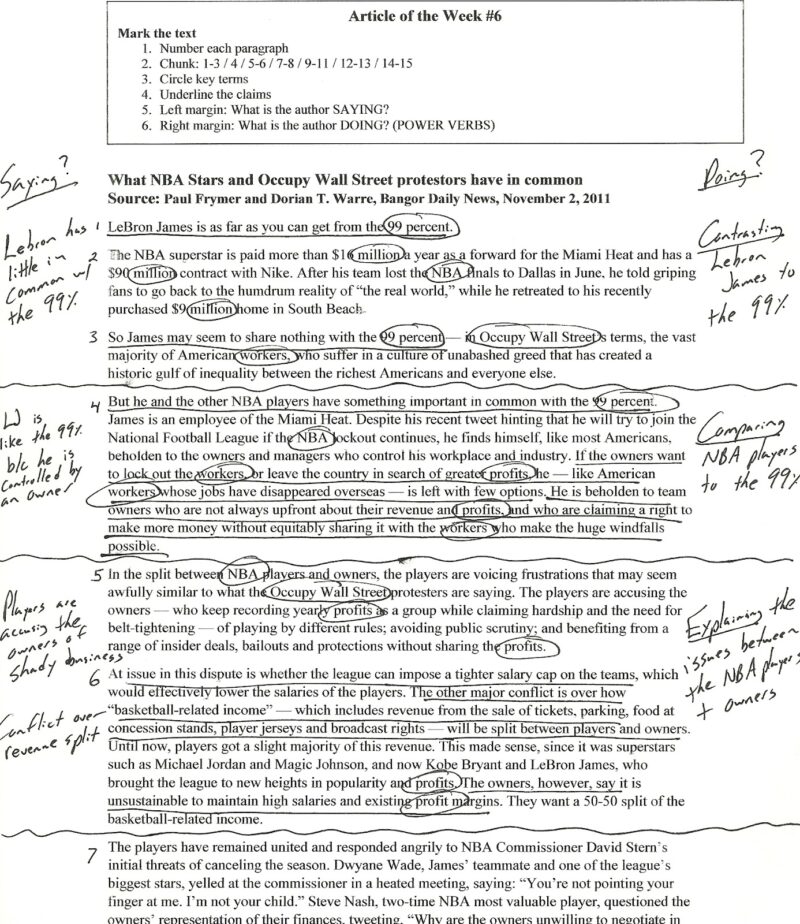

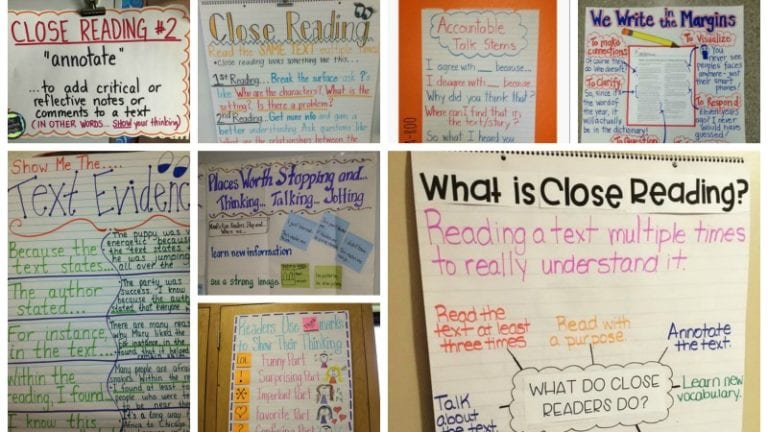

4. Highlight or Annotate the Text

Watch for important terms, definitions, facts, and phrases and highlight them or add annotations within the document—digitally if you’re on a computer. However, don't get carried away with the highlighting.

If you would rather not use a highlighter, try to annotate the text with notes in the margins or in comment mode, or underline key phrases. Also, look for and mark the main idea or thesis.

5. Take Notes on Main Points

This is different from highlighting because you can take your own notes separately. Here are a few note-taking strategies:

- Have your own style: Try bullet points, mind mapping, outlines, or whatever method works for you.

- Turn subtitles into questions: By making section headers into questions, that can help you find the answers.

- Summarize as you read: After reading a paragraph, write a sentence to summarize the paragraph’s main points. Is the author’s thesis supported? Is an opposing view introduced?

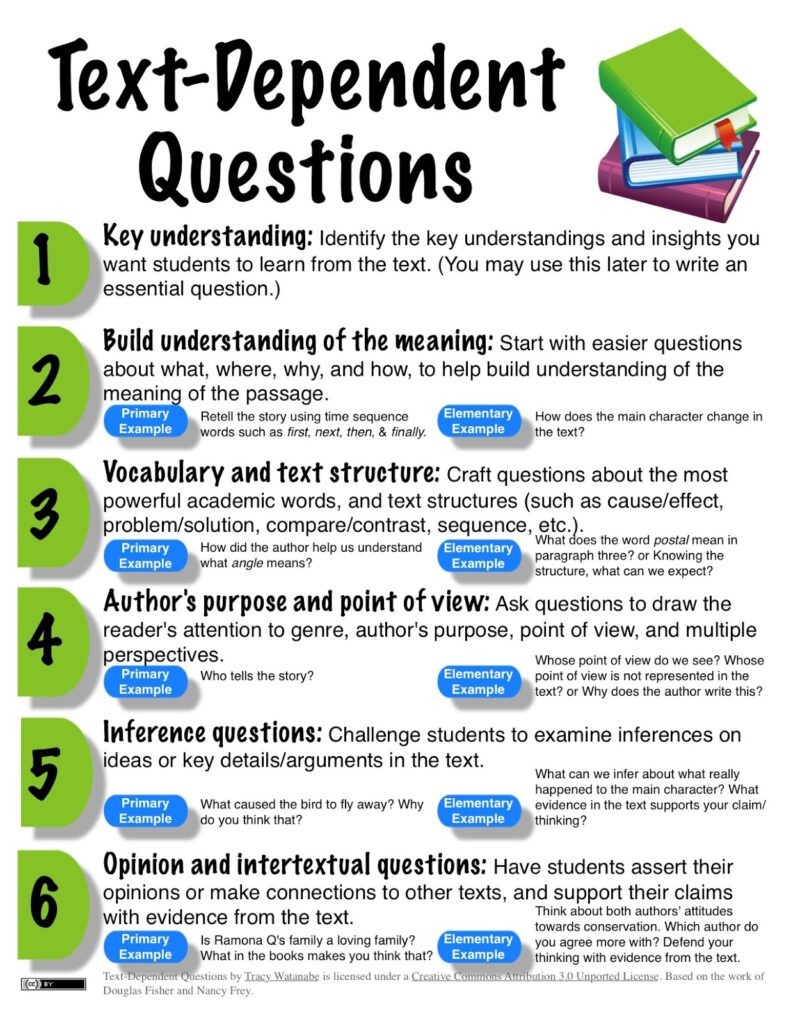

6. Write Questions as You Read

Asking questions can help your comprehension. The tactic also works when reading. Ask questions in your notes—who, what, when, where, how—and then look for answers as you continue. That helps you understand what you read.

7. Look Up Words You Don’t Know

Don’t let unfamiliar words derail you. Look them up in a dictionary before you go any further. It can be hard to recover if you miss the main point because of new words. You may want to bookmark an online dictionary, like Merriam-Webster , so you can easily find word definitions.

8. Make Connections

Look for links and connections between the text and your experiences, thoughts, ideas, and other texts.

9. Review and Summarize

After you finish reading, summarize the text in your own words. This will help you understand main ideas and take better notes. If you don’t understand what you’ve read, reread carefully.

10. Discuss What You've Read

Describe what you have learned to someone else. Talk to your professor or another classmate. Join discussion groups. This will move the information (or content) from short-term to long-term memory.

Additional Reading Comprehension Strategies and Tools

Sometimes, charting what you learned will help you digest what you’ve read. Here are some sites and tools you can use to help.

- 10 Tips to Improve Your Reading Comprehension —This YouTube video features an instructor talking about reading and sharing tips.

- Inspiration —Create concept or mind maps, graphic organizers, webs, and more to make sense of reading materials.

- Purdue Global Academic Success Centers —Assistance with business, math, science, technology, and writing is available through Purdue Global’s online Academic Success Centers.

- Purdue Global Study Essentials —This student support website offers action plans, study skills, hints on time management, and other tools to help students.

- Quizlet —Create flashcards, quizzes, and other study aids with this website.

- Rewordify —Turn arcane language into readable modern words with this free tool.

- Snap&Read —Rephrase complicated text into simpler language with this Google Chrome extension.

Learn More About Purdue Global

Get ready for the next stage of your career—or launch a totally new one—with online college at Purdue Global. Learn more about our online degree programs . For more details, request more information .

About the Author

Purdue Global

Earn a degree you're proud of and employers respect at Purdue Global, Purdue's online university for working adults. Accredited and online, Purdue Global gives you the flexibility and support you need to come back and move your career forward. Choose from 175+ programs, all backed by the power of Purdue.

- Alumni & Student Stories

- Legal Studies & Public Policy

- Online Learning

Your Path to Success Begins Here

Learn more about online programs at Purdue Global and download our program guide.

Connect with an Advisor to explore program requirements, curriculum, credit for prior learning process, and financial aid options.

Third-Party Products and Services: Links from the Purdue Global website to third-party sites do not constitute an endorsement by Purdue Global of the parties or their products and services. Purdue Global cannot guarantee that certain products will continue to be offered by their publishers for free. Users of third-party websites are responsible for reviewing the terms of use and being familiar with the privacy policy of such third-party websites.

5.2 Effective Reading Strategies

| Estimated completion time: 25 minutes. |

Questions to Consider:

- What methods can you incorporate into your routine to allow adequate time for reading?

- What are the benefits and approaches to active reading?

- Do your courses or major have specific reading requirements?

Allowing Adequate Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class very early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your instructor asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment.

Depending on the makeup of your schedule, you may end up reading both primary sources—such as legal documents, historic letters, or diaries—as well as textbooks, articles, and secondary sources, such as summaries or argumentative essays that use primary sources to stake a claim. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay current in local or global affairs. A realistic approach to scheduling your time to allow you to read and review all the reading you have for the semester will help you accomplish what can sometimes seem like an overwhelming task.

When you allow adequate time in your hectic schedule for reading, you are investing in your own success. Reading isn’t a magic pill, but it may seem like it when you consider all the benefits people reap from this ordinary practice. Famous successful people throughout history have been voracious readers. In fact, former U.S. president Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” Writer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, inventor, and also former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson claimed “I cannot live without books” at a time when keeping and reading books was an expensive pastime. Knowing what it meant to be kept from the joys of reading, 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” And finally, George R. R. Martin, the prolific author of the wildly successful Game of Thrones empire, declared, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.”

You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include determining your usual reading pace and speed, scheduling active reading sessions, and practicing recursive reading strategies.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing

To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine your average reading pace (5 times 12 equals the 60 minutes of an hour). Of course, your reading pace will be different and take longer if you are taking notes while you read, but this calculation of reading pace gives you a good way to estimate your reading speed that you can adapt to other forms of reading.

| Reader | Pages Read in 5 Minutes | Pages per Hour | Approximate Hours to Read 500 Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marta | 4 | 48 | 10 hours, 30 minutes |

| Jordi | 3 | 36 | 13 hours |

| Estevan | 5 | 60 | 8 hours, 20 minutes |

So, for instance, if Marta was able to read 4 pages of a dense novel for her English class in 5 minutes, she should be able to read about 48 pages in one hour. Knowing this, Marta can accurately determine how much time she needs to devote to finishing the novel within a set amount of time, instead of just guessing. If the novel Marta is reading is 497 pages, then Marta would take the total page count (497) and divide that by her hourly reading rate (48 pages/hour) to determine that she needs about 10 to 11 hours overall. To finish the novel spread out over two weeks, Marta needs to read a little under an hour a day to accomplish this goal.

Calculating your reading rate in this manner does not take into account days where you’re too distracted and you have to reread passages or days when you just aren’t in the mood to read. And your reading rate will likely vary depending on how dense the content you’re reading is (e.g., a complex textbook vs. a comic book). Your pace may slow down somewhat if you are not very interested in what the text is about. What this method will help you do is be realistic about your reading time as opposed to waging a guess based on nothing and then becoming worried when you have far more reading to finish than the time available.

Chapter 3 , offers more detail on how best to determine your speed from one type of reading to the next so you are better able to schedule your reading.

Scheduling Set Times for Active Reading

Active reading takes longer than reading through passages without stopping. You may not need to read your latest sci-fi series actively while you’re lounging on the beach, but many other reading situations demand more attention from you. Active reading is particularly important for college courses. You are a scholar actively engaging with the text by posing questions, seeking answers, and clarifying any confusing elements. Plan to spend at least twice as long to read actively than to read passages without taking notes or otherwise marking select elements of the text.

To determine the time you need for active reading, use the same calculations you use to determine your traditional reading speed and double it. Remember that you need to determine your reading pace for all the classes you have in a particular semester and multiply your speed by the number of classes you have that require different types of reading.

| Reader | Pages Read in 5 Minutes | Pages per Hour | Approximate Hours to Read 500 Pages | Approximate Hours to Actively Read 500 Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marta | 4 | 48 | 10 hours, 30 minutes | 21 hours |

| Jordi | 3 | 36 | 13 hours | 26 hours |

| Estevan | 5 | 60 | 8 hours, 20 minutes | 16 hours, 40 minutes |

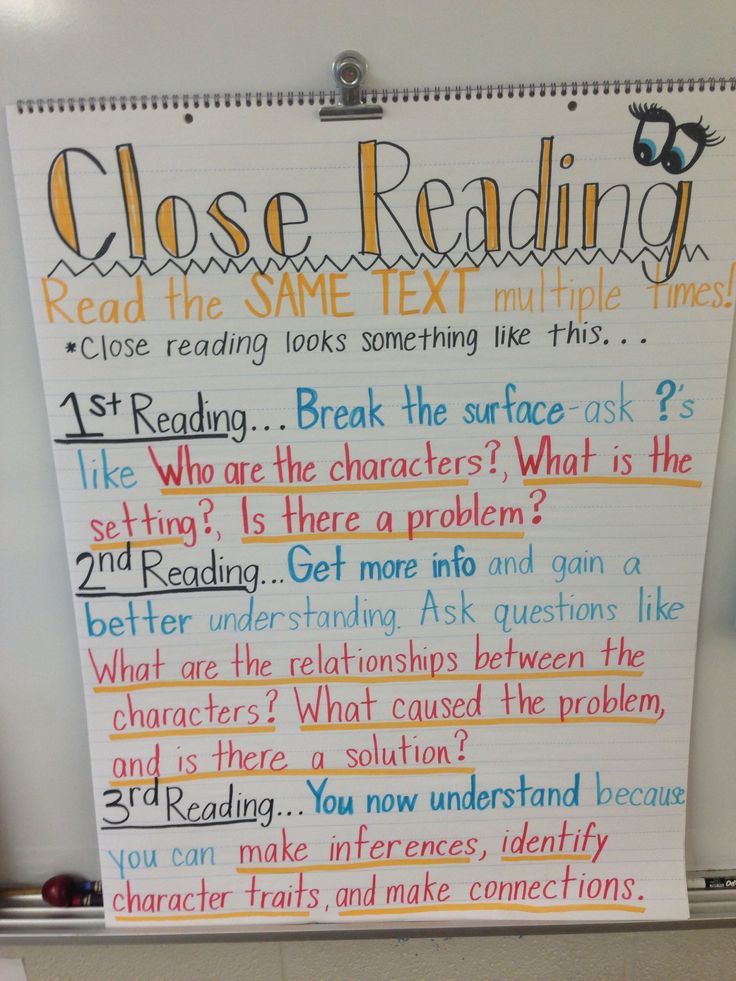

Practicing Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for college courses that may become frustrating is that, in a way, it never ends. For all the reading you do, you end up doing even more rereading. It may be the same content, but you may be reading the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This rereading is called recursive reading.

For most of what you read at the college level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose—not just because the topic interests or entertains you. You need your full attention to decipher everything that’s going on in complex reading material—and you even need to be considering what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive.

Specifically, this boils down to seeing reading not as a formula but as a process that is far more circular than linear. You may read a selection from beginning to end, which is an excellent starting point, but for comprehension, you’ll need to go back and reread passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and the bigger learning environment that led you to the selection—that may be a single course or a program in your college, or it may be the larger discipline, such as all biologists or the community of scholars studying beach erosion.

People often say writing is rewriting. For college courses, reading is rereading.

Strong readers engage in numerous steps, sometimes combining more than one step simultaneously, but knowing the steps nonetheless. They include, not always in this order:

- bringing any prior knowledge about the topic to the reading session,

- asking yourself pertinent questions, both orally and in writing, about the content you are reading,

- inferring and/or implying information from what you read,

- learning unfamiliar discipline-specific terms,

- evaluating what you are reading, and eventually,

- applying what you’re reading to other learning and life situations you encounter.

Let’s break these steps into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

Application

Imagining that you were given a chapter to read in your American history class about the Gettysburg Address, write down what you already know about this historic document. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text?

Asking Questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my professor assign this reading?

You need a place where you can actually write down these questions; a separate page in your notes is a good place to begin. If you are taking notes on your computer, start a new document and write down the questions. Leave some room to answer the questions when you begin and again after you read.

Inferring and Implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer , or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the professor will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test.

Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer may not want to come out explicitly and state a bias, but may imply or hint at his or her preference for one political party or another. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning Vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. Few people beyond undertakers and archeologists likely use the term sarcophagus in everyday communications, but for those disciplines, it is a meaningful distinction. Looking at the example, you can use context clues to figure out the meaning of the term sarcophagus because it is something undertakers and/or archeologists would recognize. At the very least, you can guess that it has something to do with death. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Intelligent people always question and evaluate. This doesn’t mean they don’t trust others; they just need verification of facts to understand a topic well. It doesn’t make sense to learn incomplete or incorrect information about a subject just because you didn’t take the time to evaluate all the sources at your disposal. When early explorers were afraid to sail the world for fear of falling off the edge, they weren’t stupid; they just didn’t have all the necessary data to evaluate the situation.

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings.

- Read through the entire passage fully.

- Question what main point the author is making.

- Decide who the audience is.

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses.

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point.

- Recognize if the author introduced any biases in the text.

When you go through a text looking for each of these elements, you need to go beyond just answering the surface question; for instance, the audience may be a specific field of scientists, but could anyone else understand the text with some explanation? Why would that be important?

Analysis Question

Think of an article you need to read for a class. Take the steps above on how to evaluate a text, and apply the steps to the article. When you accomplish the task in each step, ask yourself and take notes to answer the question: Why is this important? For example, when you read the title, does that give you any additional information that will help you comprehend the text? If the text were written for a different audience, what might the author need to change to accommodate that group? How does an author’s bias distort an argument? This deep evaluation allows you to fully understand the main ideas and place the text in context with other material on the same subject, with current events, and within the discipline.

When you learn something new, it always connects to other knowledge you already have. One challenge we have is applying new information. It may be interesting to know the distance to the moon, but how do we apply it to something we need to do? If your biology instructor asked you to list several challenges of colonizing Mars and you do not know much about that planet’s exploration, you may be able to use your knowledge of how far Earth is from the moon to apply it to the new task. You may have to read several other texts in addition to reading graphs and charts to find this information.

That was the challenge the early space explorers faced along with myriad unknowns before space travel was a more regular occurrence. They had to take what they already knew and could study and read about and apply it to an unknown situation. These explorers wrote down their challenges, failures, and successes, and now scientists read those texts as a part of the ever-growing body of text about space travel. Application is a sophisticated level of thinking that helps turn theory into practice and challenges into successes.

Preparing to Read for Specific Disciplines in College

Different disciplines in college may have specific expectations, but you can depend on all subjects asking you to read to some degree. In this college reading requirement, you can succeed by learning to read actively, researching the topic and author, and recognizing how your own preconceived notions affect your reading. Reading for college isn’t the same as reading for pleasure or even just reading to learn something on your own because you are casually interested.

In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, books, or primary sources (those original documents about which we write and study, such as letters between historic figures or the Declaration of Independence). Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

If you are about to participate in an in-depth six-week consideration of the U.S. Constitution but have never read it or anything written about it, you will have a hard time looking at anything in detail or understanding how and why it is significant. As you can imagine, a great deal has been written about the Constitution by scholars and citizens since the late 1700s when it was first put to paper (that’s how they did it then). While the actual document isn’t that long (about 12–15 pages depending on how it is presented), learning the details on how it came about, who was involved, and why it was and still is a significant document would take a considerable amount of time to read and digest. So, how do you do it all? Especially when you may have an instructor who drops hints that you may also love to read a historic novel covering the same time period . . . in your spare time , not required, of course! It can be daunting, especially if you are taking more than one course that has time-consuming reading lists. With a few strategic techniques, you can manage it all, but know that you must have a plan and schedule your required reading so you are also able to pick up that recommended historic novel—it may give you an entirely new perspective on the issue.

Strategies for Reading in College Disciplines

No universal law exists for how much reading instructors and institutions expect college students to undertake for various disciplines. Suffice it to say, it’s a LOT.

For most students, it is the volume of reading that catches them most off guard when they begin their college careers. A full course load might require 10–15 hours of reading per week, some of that covering content that will be more difficult than the reading for other courses.

You cannot possibly read word-for-word every single document you need to read for all your classes. That doesn’t mean you give up or decide to only read for your favorite classes or concoct a scheme to read 17 percent for each class and see how that works for you. You need to learn to skim, annotate, and take notes. All of these techniques will help you comprehend more of what you read, which is why we read in the first place. We’ll talk more later about annotating and note-taking, but for now consider what you know about skimming as opposed to active reading.

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page (or screen) to see if any of it sticks. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage without the need for a time-consuming reading session that involves your active use of notations and annotations. Often you will need to engage in that painstaking level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. The fact remains that neither do you need to read everything nor could you possibly accomplish that given your limited time. So learn this valuable skill of skimming as an accompaniment to your overall study tool kit, and with practice and experience, you will fully understand how valuable it is.

When you skim, look for guides to your understanding: headings, definitions, pull quotes, tables, and context clues. Textbooks are often helpful for skimming—they may already have made some of these skimming guides in bold or a different color, and chapters often follow a predictable outline. Some even provide an overview and summary for sections or chapters. Use whatever you can get, but don’t stop there. In textbooks that have some reading guides, or especially in text that does not, look for introductory words such as First or The purpose of this article . . . or summary words such as In conclusion . . . or Finally . These guides will help you read only those sentences or paragraphs that will give you the overall meaning or gist of a passage or book.

Now move to the meat of the passage. You want to take in the reading as a whole. For a book, look at the titles of each chapter if available. Read each chapter’s introductory paragraph and determine why the writer chose this particular order. Depending on what you’re reading, the chapters may be only informational, but often you’re looking for a specific argument. What position is the writer claiming? What support, counterarguments, and conclusions is the writer presenting?

Don’t think of skimming as a way to buzz through a boring reading assignment. It is a skill you should master so you can engage, at various levels, with all the reading you need to accomplish in college. End your skimming session with a few notes—terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. And recognize that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading differs significantly from skimming or reading for pleasure. You can think of active reading as a sort of conversation between you and the text (maybe between you and the author, but you don’t want to get the author’s personality too involved in this metaphor because that may skew your engagement with the text).

When you sit down to determine what your different classes expect you to read and you create a reading schedule to ensure you complete all the reading, think about when you should read the material strategically, not just how to get it all done . You should read textbook chapters and other reading assignments before you go into a lecture about that information. Don’t wait to see how the lecture goes before you read the material, or you may not understand the information in the lecture. Reading before class helps you put ideas together between your reading and the information you hear and discuss in class.

Different disciplines naturally have different types of texts, and you need to take this into account when you schedule your time for reading class material. For example, you may look at a poem for your world literature class and assume that it will not take you long to read because it is relatively short compared to the dense textbook you have for your economics class. But reading and understanding a poem can take a considerable amount of time when you realize you may need to stop numerous times to review the separate word meanings and how the words form images and connections throughout the poem.

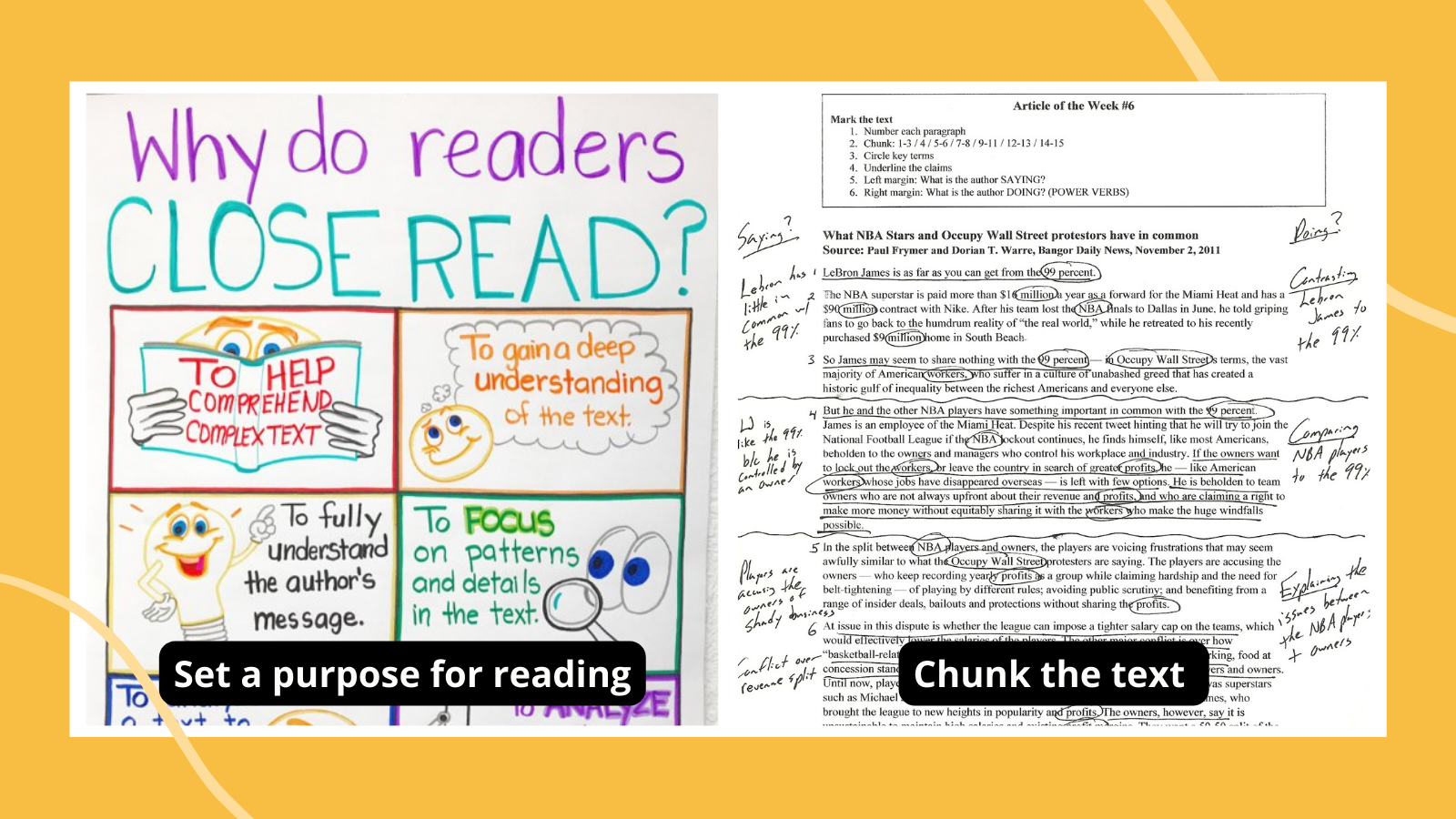

The SQ3R Reading Strategy

You may have heard of the SQ3R method for active reading in your early education. This valuable technique is perfect for college reading. The title stands for S urvey, Q uestion, R ead, R ecite, R eview, and you can use the steps on virtually any assigned passage. Designed by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1961 book Effective Study, the active reading strategy gives readers a systematic way to work through any reading material.

Survey is similar to skimming. You look for clues to meaning by reading the titles, headings, introductions, summary, captions for graphics, and keywords. You can survey almost anything connected to the reading selection, including the copyright information, the date of the journal article, or the names and qualifications of the author(s). In this step, you decide what the general meaning is for the reading selection.

Question is your creation of questions to seek the main ideas, support, examples, and conclusions of the reading selection. Ask yourself these questions separately. Try to create valid questions about what you are about to read that have come into your mind as you engaged in the Survey step. Try turning the headings of the sections in the chapter into questions. Next, how does what you’re reading relate to you, your school, your community, and the world?

Read is when you actually read the passage. Try to find the answers to questions you developed in the previous step. Decide how much you are reading in chunks, either by paragraph for more complex readings or by section or even by an entire chapter. When you finish reading the selection, stop to make notes. Answer the questions by writing a note in the margin or other white space of the text.

You may also carefully underline or highlight text in addition to your notes. Use caution here that you don’t try to rush this step by haphazardly circling terms or the other extreme of underlining huge chunks of text. Don’t over-mark. You aren’t likely to remember what these cryptic marks mean later when you come back to use this active reading session to study. The text is the source of information—your marks and notes are just a way to organize and make sense of that information.

Recite means to speak out loud. By reciting, you are engaging other senses to remember the material—you read it (visual) and you said it (auditory). Stop reading momentarily in the step to answer your questions or clarify confusing sentences or paragraphs. You can recite a summary of what the text means to you. If you are not in a place where you can verbalize, such as a library or classroom, you can accomplish this step adequately by saying it in your head; however, to get the biggest bang for your buck, try to find a place where you can speak aloud. You may even want to try explaining the content to a friend.

Review is a recap. Go back over what you read and add more notes, ensuring you have captured the main points of the passage, identified the supporting evidence and examples, and understood the overall meaning. You may need to repeat some or all of the SQR3 steps during your review depending on the length and complexity of the material. Before you end your active reading session, write a short (no more than one page is optimal) summary of the text you read.

Reading Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary sources are original documents we study and from which we glean information; primary sources include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Readers have to keep several factors in mind when reading both primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. It may contain personal beliefs and biases the original writer didn’t intent to be openly published, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases or preferences the secondary source writer inserts in the writing that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner.

For example, if you were to read a secondary source that is examining the U.S. Declaration of Independence (the primary source), you would have a much clearer idea of how the secondary source scholar presented the information from the primary source if you also read the Declaration for yourself instead of trusting the other writer’s interpretation. Most scholars are honest in writing secondary sources, but you as a reader of the source are trusting the writer to present a balanced perspective of the primary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source. The Internet helps immensely with this practice.

What Students Say

- How engaging the material is or how much I enjoy reading it.

- Whether or not the course is part of my major.

- Whether or not the instructor assesses knowledge from the reading (through quizzes, for example), or requires assignments based on the reading.

- Whether or not knowledge or information from the reading is required to participate in lecture.

- I read all of the assigned material.

- I read most of the assigned material.

- I skim the text and read the captions, examples, or summaries.

- I use a systematic method such as the Cornell method or something similar.

- I highlight or underline all the important information.

- I create outlines and/or note-cards.

- I use an app or program.

- I write notes in my text (print or digital).

- I don’t have a style. I just write down what seems important.

- I don't take many notes.

You can also take the anonymous What Students Say surveys to add your voice to this textbook. Your responses will be included in updates.

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

What is the most influential factor in how thoroughly you read the material for a given course?

What best describes your reading approach for required texts/materials for your classes?

What best describes your note-taking style?

Researching Topic and Author

During your preview stage, sometimes called pre-reading, you can easily pick up on information from various sources that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. If your selection is a book, flip it over or turn to the back pages and look for an author’s biography or note from the author. See if the book itself contains any other information about the author or the subject matter.

The main things you need to recall from your reading in college are the topics covered and how the information fits into the discipline. You can find these parts throughout the textbook chapter in the form of headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations pulled out of the narrative. Use these features as you read to help you determine what the most important ideas are.

Remember, many books use quotations about the book or author as testimonials in a marketing approach to sell more books, so these may not be the most reliable sources of unbiased opinions, but it’s a start. Sometimes you can find a list of other books the author has written near the front of a book. Do you recognize any of the other titles? Can you do an Internet search for the name of the book or author? Go beyond the search results that want you to buy the book and see if you can glean any other relevant information about the author or the reading selection. Beyond a standard Internet search, try the library article database. These are more relevant to academic disciplines and contain resources you typically will not find in a standard search engine. If you are unfamiliar with how to use the library database, ask a reference librarian on campus. They are often underused resources that can point you in the right direction.

Understanding Your Own Preset Ideas on a Topic

Laura really enjoys learning about environmental issues. She has read many books and watched numerous televised documentaries on this topic and actively seeks out additional information on the environment. While Laura’s interest can help her understand a new reading encounter about the environment, Laura also has to be aware that with this interest, she also brings forward her preset ideas and biases about the topic. Sometimes these prejudices against other ideas relate to religion or nationality or even just tradition. Without evidence, thinking the way we always have is not a good enough reason; evidence can change, and at the very least it needs honest review and assessment to determine its validity. Ironically, we may not want to learn new ideas because that may mean we would have to give up old ideas we have already mastered, which can be a daunting prospect.

With every reading situation about the environment, Laura needs to remain open-minded about what she is about to read and pay careful attention if she begins to ignore certain parts of the text because of her preconceived notions. Learning new information can be very difficult if you balk at ideas that are different from what you’ve always thought. You may have to force yourself to listen to a different viewpoint multiple times to make sure you are not closing your mind to a viable solution your mindset does not currently allow.

Can you think of times you have struggled reading college content for a course? Which of these strategies might have helped you understand the content? Why do you think those strategies would work?

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Amy Baldwin

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Success

- Publication date: Mar 27, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/5-2-effective-reading-strategies

© Sep 20, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Teach the Seven Strategies of Highly Effective Readers

To improve students’ reading comprehension, teachers should introduce the seven cognitive strategies of effective readers: activating, inferring, monitoring-clarifying, questioning, searching-selecting, summarizing, and visualizing-organizing. This article includes definitions of the seven strategies and a lesson-plan template for teaching each one.

To assume that one can simply have students memorize and routinely execute a set of strategies is to misconceive the nature of strategic processing or executive control. Such rote applications of these procedures represents, in essence, a true oxymoron-non-strategic strategic processing. — Alexander and Murphy (1998, p. 33)

If the struggling readers in your content classroom routinely miss the point when “reading” content text, consider teaching them one or more of the seven cognitive strategies of highly effective readers. Cognitive strategies are the mental processes used by skilled readers to extract and construct meaning from text and to create knowledge structures in long-term memory. When these strategies are directly taught to and modeled for struggling readers, their comprehension and retention improve.

Struggling students often mistakenly believe they are reading when they are actually engaged in what researchers call mindless reading (Schooler, Reichle, & Halpern, 2004), zoning out while staring at the printed page. The opposite of mindless reading is the processing of text by highly effective readers using cognitive strategies. These strategies are described in a fascinating qualitative study that asked expert readers to think aloud regarding what was happening in their minds while they were reading. The lengthy scripts recording these spoken thoughts (i.e., think-alouds) are called verbal protocols (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). These protocols were categorized and analyzed by researchers to answer specific questions, such as, What is the influence of prior knowledge on expert readers’ strategies as they determine the main idea of a text? (Afflerbach, 1990b).

The protocols provide accurate “snapshots” and even “videos” of the ever-changing mental landscape that expert readers construct during reading. Researchers have concluded that reading is “constructively responsive-that is, good readers are always changing their processing in response to the text they are reading” (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995, p. 2). Instructional Aid 1.1 defines the seven cognitive strategies of highly effective readers, and Instructional Aid 1.2 provides a lesson plan template for teaching a cognitive strategy.

Instructional aids

| Activating | “Priming the cognitive pump” in order to recall relevent prior knowledge and experiences from long-term memory in order to extract and construct meaning from text |

| Inferring | Bringing together what is spoken (written) in the text, what is unspoken (unwritten) in the text, and what is already known by the reader in order to extract and construct meaning from the text |

| Monitoring-Clarifying | Thinking about how and what one is reading, both during and after the act of reading, for purposes of determining if one is comprehending the text combined with the ability to clarify and fix up any mix-ups |

| Questioning | Engaging in learning dialogues with text (authors), peers, and teachers through self-questioning, question generation, and question answering |

| Searching-Selecting | Searching a variety of sources in order to select appropriate information to answer questions, define words and terms, clarify misunderstandings, solve problems, or gather information |

| Summarizing | Restating the meaning of text in one’s own words — different words from those used in the original text |

| Visualizing-Organizing | Constructing a mental image or graphic organizer for the purpose of extracting and constructing meaning from the text |

| (8K PDF)* |

| 1. Provide direct instruction regarding the cognitive strategy | |

| a. Define and explain the strategy | |

| b. Explain the purpose the strategy serves during reading | |

| c. Describe the critical attributes of the strategy | |

| d. Provide concrete examples/nonexamples of the strategy | |

| 2. Model the strategy by thinking aloud | |

| 3. Facilitate guided practice with students | |

| (opens in a new window) (8K PDF)* |

| 1. Provide direct instruction regarding the cognitive strategy | |

| a. Define and explain the strategy. | Summarizing is restating in your own words the meaning of what you have read—using different words from those used in the original text—either in written form or a graphic representation (picture of graphic organizer). |

| b. Explain the purpose the strategy serves during reading | Summarizing enables a reader to determine what is most imporant to remember once the reading is completed. Many things we read have only one or two bid ideas, and it’s important to identify them and restate them for purposed of retention. |

| c. Describe the critical attributes of the strategy. | A summary has the following characteristics. It: –Is short –Is to the point, containing the big idea of the text –Omits trivial information and collapses lists into a word or phrase –Is not a retelling or a “photocopy” of the text |

| d. Provide concrete examples/nonexamples of the strategy. | Examples of good summaries might inlude the one-sentence book summaries from The New York Times Bestsellers List, an obituary of a famous person, or a report of a basketball or football game that captures the highlights. The mistakes that students commonly make when writing summaries can be more readily avoided by showing students excellent nonexamples (e.g., a paragraph that is too long, has far too many details, or is a complete retelling of the text rather than a statement of the main idea. |

| 2. Model the strategy by thinking aloud. | Thinking aloud is a metacognitive activity in which teachers reflect on their behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes regarding what they have read and then speak their thoughts aloud for students. Choose a section of relatively easy text from your discipline and think aloud as you read it, and then also think aloud about how you would go about summarizing it — then do it. |

| 3. Facilitate guided practice with students. | Using easy-to-read content text, read aloud and generate a summary together with the whole class. Using easy-to-read content text, ask students to read with partners and create a summary together. One students are writing good summaries as partners, assign text and expect students to read it and generate summaries independently. |

| (opens in a new window) (9K PDF)* |

Liked it? Share it!

McEwan, 2004. 7 Strategies of Highly Effective Readers: Using Cognitive Research to Boost K-8 Achievement. Wood, Woloshyn, & Willoughby, 1995. Cognitive Strategy Instruction for Middle and High Schools.

McEwan, E.K., 40 Ways to Support Struggling Readers in Content Classrooms. Grades 6-12, pp.1-6, copyright 2007 by Corwin Press. Reprinted by permission of Corwin Press, Inc.

Visit our sister websites:

Reading rockets launching young readers (opens in a new window), start with a book read. explore. learn (opens in a new window), colorín colorado helping ells succeed (opens in a new window), ld online all about learning disabilities (opens in a new window), reading universe all about teaching reading and writing (opens in a new window).

Learning Corner

- Where Do I Start?

- All Worksheets

- Improve Performance

- Manage & Make Time

- Procrasti-NOT

- Works Cited/Referenced/Researched

- Remote & Online Learning

- Less Stress

- How-To Videos

You are here

Reading strategies & tips.

Reading is a foundational learning activity for college-level courses. Assigned readings prepare you for taking notes during lectures and provide you with additional examples and detail that might not be covered in class. Also, according to research, readings are the second most frequent source of exam questions (Cuseo, Fecas & Thompson, 2007).

Reading a college textbook effectively takes practice and should be approached differently than reading a novel, comic book, magazine, or website. Becoming an effective reader goes beyond completing the reading in full or highlighting text. There are a variety of strategies you can use to read effectively and retain the information you read.

Consider the following quick tips and ideas to make the most of your reading time:

- Schedule time to read . Reading is an easy thing to put off because there is often no exact due date. By scheduling a time each week to do your reading for each class, you are more likely to complete the reading as if it were an assignment. Producing a study guide or set of notes from the reading can help to direct your thinking as you read.

- Set yourself up for success . Pick a location that is conducive to reading. Establish a reasonable goal for the reading, and a time limit for how long you’ll be working. These techniques make reading feel manageable and make it easier to get started and finish reading.

- Choose and use a specific reading strategy . There are many strategies that will help you actively read and retain information (PRR or SQ3R – see the handouts and videos). By consciously choosing a way to approach your reading, you can begin the first step of exam preparation or essay writing. Remember: good readers make stronger writers.

- Monitor your comprehension . When you finish a section, ask yourself, "What is the main idea in this section? Could I answer an exam question about this topic?" Questions at the end of chapters are particularly good for focusing your attention and for assessing your comprehension. If you are having difficulty recalling information or answering questions about the text, search back through the text and look for key points and answers. Self-correction techniques like revisiting the text are essential to assessing your comprehension and are a hallmark technique of advanced readers (Caverly & Orlando, 1991).

- Take notes as you read . Whether they’re annotations in the margins of the book, or notes on a separate piece of paper. Engage with the reading through your notes – ask questions, answer questions, make connections, and think about how these ideas integrate with other information sources (like lecture, lab, other readings, etc.)

Want to dive in a little deeper? Take a look at Kathleen King's tips below to help you get the most out of your reading, and to read for success. You'll see that some are similar to the tips above, but some offer new approaches and ideas; see what works for you:

- Read sitting up with good light, and at a desk or table.

- Keep background noise to a minimum . Loud rock music will not make you a better reader. The same goes for other distractions: talking to roommates, kids playing nearby, television or radio. Give yourself a quiet environment so that you can concentrate on the text.

- Keep paper and pen within reach .

- Before beginning to read, think about the purpose of the reading . Why has the teacher assigned the reading? What are you supposed to get out of it? Jot down your thoughts.

- Survey the reading . Look at the title of the piece, the subheadings. What is in the dark print or stands out? Are there illustrations or graphs?

- Strategize your approach : read the introduction and conclusion, then go back and read the whole assignment, or read the first line in every paragraph to get an idea of how the ideas progress, then go back and read from the beginning.

- Scan effectively : scan the entire reading, and then focus on the most interesting or relevant parts to read in detail.

- Get a feel for what's expected of you by the reading . Pay attention to when you can skim and when you need to understand every word.

- Write as you read . Take notes and talk back to the text. Explain in detail the concepts. Mark up the pages. Ask questions. Write possible test questions. Write down what interests or bores you. Speculate about why.

- If you get stuck : think and write about where you got stuck. Contemplate why that particular place was difficult and how you might break through the block.

- Record and explore your confusion . Confusion is important because it’s the first stage in understanding.

- When the going gets difficult, and you don’t understand the reading , slow down and reread sections. Try to explain them to someone, or have someone else read the section and talk through it together.

- Break long assignments into segments . Read 10 pages (and take notes) then do something else. Later, read the next 10 pages and so on.

- Read prefaces and summaries to learn important details about the book. Look at the table of contents for information about the structure and movement of ideas. Use the index to look up specific names, places, ideas.

(Reading strategies by Dr. Kathleen King. Many of the above ideas are from a lecture by Dr. Lee Haugen, former Reading specialist at the ISU Academic Skills Center. https://www.ghc.edu/sites/default/files/StudentResources/documents/learn... )

Curious to learn more? Check out our Reading video , and hear what we have to say!

WE'RE HERE TO HELP:

Summer Hours Drop In: Wednesdays, 10am to 4pm PST 125 Waldo Hall Our drop-in space will be closed on Wednesday, June 19th for Juneteenth.

Call or Email: Mon-Fri, 9am to 5pm PST 541-737-2272 [email protected]

Use of ASC Materials

Use & Attribution Info

Contact Info

- Categories: Engaging with Courses , Strategies for Learning

Reading is one of the most important components of college learning, and yet it’s one we often take for granted. Of course, students who come to Harvard know how to read, but many are unaware that there are different ways to read and that the strategies they use while reading can greatly impact memory and comprehension. Furthermore, students may find themselves encountering kinds of texts they haven’t worked with before, like academic articles and books, archival material, and theoretical texts.

So how should you approach reading in this new environment? And how do you manage the quantity of reading you’re asked to cover in college?

Start by asking “Why am I reading this?”

To read effectively, it helps to read with a goal . This means understanding before you begin reading what you need to get out of that reading. Having a goal is useful because it helps you focus on relevant information and know when you’re done reading, whether your eyes have seen every word or not.

Some sample reading goals:

- To find a paper topic or write a paper;

- To have a comment for discussion;

- To supplement ideas from lecture;

- To understand a particular concept;

- To memorize material for an exam;

- To research for an assignment;

- To enjoy the process (i.e., reading for pleasure!).

Your goals for reading are often developed in relation to your instructor’s goals in assigning the reading, but sometimes they will diverge. The point is to know what you want to get out of your reading and to make sure you’re approaching the text with that goal in mind. Write down your goal and use it to guide your reading process.

Next, ask yourself “How should I read this?”

Not every text you’re assigned in college should be read the same way. Depending on the type of reading you’re doing and your reading goal, you may find that different reading strategies are most supportive of your learning. Do you need to understand the main idea of your text? Or do you need to pay special attention to its language? Is there data you need to extract? Or are you reading to develop your own unique ideas?

The key is to choose a reading strategy that will help you achieve your reading goal. Factors to consider might be:

- The timing of your reading (e.g., before vs. after class)

- What type of text you are reading (e.g., an academic article vs. a novel)

- How dense or unfamiliar a text is

- How extensively you will be using the text

- What type of critical thinking (if any) you are expected to bring to the reading

Based on your consideration of these factors, you may decide to skim the text or focus your attention on a particular portion of it. You also might choose to find resources that can assist you in understanding the text if it is particularly dense or unfamiliar. For textbooks, you might even use a reading strategy like SQ3R .

Finally, ask yourself “How long will I give this reading?”

Often, we decide how long we will read a text by estimating our reading speed and calculating an appropriate length of time based on it. But this can lead to long stretches of engaging ineffectually with texts and losing sight of our reading goals. These calculations can also be quite inaccurate, since our reading speed is often determined by the density and familiarity of texts, which varies across assignments.

For each text you are reading, ask yourself “based on my reading goal, how long does this reading deserve ?” Sometimes, your answer will be “This is a super important reading. So, it takes as long as it takes.” In that case, create a time estimate using your best guess for your reading speed. Add some extra time to your estimate as a buffer in case your calculation is a little off. You won’t be sad to finish your reading early, but you’ll struggle if you haven’t given yourself enough time.

For other readings, once we ask how long the text deserves, we will realize based on our other academic commitments and a text’s importance in the course that we can only afford to give a certain amount of time to it. In that case, you want to create a time limit for your reading. Try to come up with a time limit that is appropriate for your reading goal. For instance, let’s say I am working with an academic article. I need to discuss it in class, but I can only afford to give it thirty minutes of time because we’re reading several articles for that class. In this case, I will set an alarm for thirty minutes and spend that time understanding the thesis/hypothesis and looking through the research to look for something I’d like to discuss in class. In this case, I might not read every word of the article, but I will spend my time focusing on the most important parts of the text based on how I need to use it.

If you need additional guidance or support, reach out to the course instructor and the ARC.

If you find yourself struggling through the readings for a course, you can ask the course instructor for guidance. Some ways to ask for help are: “How would you recommend I go about approaching the reading for this course?” or “Is there a way for me to check whether I am getting what I should be out of the readings?”

If you are looking for more tips on how to read effectively and efficiently, book an appointment with an academic coach at the ARC to discuss your specific assignments and how you can best approach them!

Seeing Textbooks in a New Light

Textbooks can be a fantastic supportive resource for your learning. They supplement the learning you’ll do in the classroom and can provide critical context for the material you cover there. In some courses, the textbook may even have been written by the professor to work in harmony with lectures.

There are a variety of ways in which professors use textbooks, so you need to assess critically how and when to read the textbook in each course you take.

Textbooks can provide:

- A fresh voice through which to absorb material. For challenging concepts, they can offer new language and details that might fill in gaps in your understanding.

- The chance to “preview” lecture material, priming your mind for the big ideas you’ll be exposed to in class.

- The chance to review material, making sense of the finer points after class.

- A resource that is accessible any time, whether it’s while you are studying for an exam, writing a paper, or completing a homework assignment.

Textbook reading is similar to and different from other kinds of reading . Some things to keep in mind as you experiment with its use:

The answer is “both” and “it depends.” In general, reading or at least previewing the assigned textbook material before lecture will help you pay attention in class and pull out the more important information from lecture, which also tends to make note-taking easier. If you read the textbook before class, then a quick review after lecture is useful for solidifying the information in memory, filling in details that you missed, and addressing gaps in your understanding. In addition, reading before and/or after class also depends on the material, your experience level with it, and the style of the text. It’s a good idea to experiment with when works best for you!

Just like other kinds of course reading, it is still important to read with a goal . Focus your reading goals on the particular section of the textbook that you are reading: Why is it important to the course I’m taking? What are the big takeaways? Also take note of any questions you may have that are still unresolved.

Reading linearly (left to right and top to bottom) does not always make the most sense. Try to gain a sense of the big ideas within the reading before you start: Survey for structure, ask Questions, and then Read – go back to flesh out the finer points within the most important and detail-rich sections.

Summarizing pushes you to identify the main points of the reading and articulate them succinctly in your own words, making it more likely that you will be able to retrieve this information later. To further strengthen your retrieval abilities, quiz yourself when you are done reading and summarizing. Quizzing yourself allows what you’ve read to enter your memory with more lasting potential, so you’ll be able to recall the information for exams or papers.

Marking Text

Marking text, which often involves making marginal notes, helps with reading comprehension by keeping you focused. It also helps you find important information when reviewing for an exam or preparing to write an essay. The next time you’re reading, write notes in the margins as you go or, if you prefer, make notes on a separate document.

Your marginal notes will vary depending on the type of reading. Some possible areas of focus:

- What themes do you see in the reading that relate to class discussions?

- What themes do you see in the reading that you have seen in other readings?

- What questions does the reading raise in your mind?

- What does the reading make you want to research more?

- Where do you see contradictions within the reading or in relation to other readings for the course?

- Can you connect themes or events to your own experiences?

Your notes don’t have to be long. You can just write two or three words to jog your memory. For example, if you notice that a book has a theme relating to friendship, you can just write, “pp. 52-53 Theme: Friendship.” If you need to remind yourself of the details later in the semester, you can re-read that part of the text more closely.

Reading Workshops

If you are looking for help with developing best practices and using strategies for some of the tips listed above, come to an ARC workshop on reading!

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Study Skills

Effective Reading

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Top Tips for Study

- Staying Motivated When Studying

- Student Budgeting and Economic Skills

- Getting Organised for Study

- Finding Time to Study

- Sources of Information

- Assessing Internet Information

- Using Apps to Support Study

- What is Theory?

- Styles of Writing

- Critical Reading

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Planning an Essay

- How to Write an Essay

- The Do’s and Don’ts of Essay Writing

- How to Write a Report

- Academic Referencing

- Assignment Finishing Touches

- Reflecting on Marked Work

- 6 Skills You Learn in School That You Use in Real Life

- Top 10 Tips on How to Study While Working

- Exam Skills

Get the SkillsYouNeed Study Skills eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

When studying, especially at higher levels, a great deal of time is spent reading.

Academic reading should not be seen as a passive activity, but an active process that leads to the development of learning.

Reading for learning requires a conscious effort to make links, understand opinions, research and apply what you learn to your studies.

This page covers the following areas: how reading develops, the goals of reading, approaching reading with the right attitude and developing a reading strategy.

Everything we read tells us something about the person who wrote it. Paying close attention to how and why the author writes something will open ourselves up to their perspective on life, which in turn enriches our understanding of the world we live in.

How Reading Develops

Learning to read as a child usually results in the ability to read simple material relatively easily.

As we develop our skills in reading, the process often becomes more challenging. We are introduced to new vocabulary and more complex sentence structures. Early school textbooks offer us facts or ‘truths’ about the world which we are required to learn; we are not, at this stage encouraged to question the authority of the writers of these published materials.

As schooling progresses however, we are led to consider a range of perspectives, or ways of looking at a topic, rather than just one. We learn to compare these perspectives and begin to form opinions about them.

This change in reading from a surface approach (gathering facts) to a deep approach (interpreting) is essential in order to gain the most out of our studies.

Reading becomes not simply a way to see what is said but to recognise and interpret what is said, taking into account subtleties such as bias, assumptions and the perspectives of the author.

Academic reading, therefore, means understanding the author’s interpretation of reality, which may be very different from our own.

The Goal of Reading

Most of us read in everyday life for different purposes – you are reading this page now, for a purpose.

We read to gain factual information for practical use, for example, a train timetable or a cinema listing. For such documents we rarely need to analyse or interpret.

We may also read fiction in order to be entertained; depending upon the reader, a level of interpretation may be applied, and if reading fiction as part of an English Literature degree, then analysis of the author’s writing style, motives etc. is imperative.

Many of us read newspapers and magazines, either in print or online, to inform us about current events. In some cases the bias of the writer is explicit and this leads us to interpret what is said in light of this bias. It is therefore easy to view a particular article as a statement of opinion rather than fact. Political biases, for example, are well known in the press.

When reading academic material such as textbooks, journals and so on, you should be always reading to interpret and analyse. Nothing should be taken as fact or ‘truth’. You will be engaged in, what is termed as, critical reading .

When you read while studying an academic course, your principal goal will be to gather information in order to answer an assignment question or gain further information on a subject for an exam or other type of assessment.

Underlying this is the more general theme of learning and development, to develop your thoughts, to incorporate new ideas into your existing understanding, to see things from different angles or view-points, to develop your knowledge and understanding and ultimately yourself.

Learning therefore comes about from developing your understanding of the meaning of the details. It is therefore crucial to engage with the text as you read, in a process called active reading.

Active Reading

Active reading is the process of engaging with the text as you read. Techniques for making your reading more active include:

Underlining or highlighting key phrases as you read . This can be a useful way to remind yourself about what you thought was important when you reread the text later. However, it is important not to highlight too much. You might, for example, consider reading a paragraph at a time before highlighting or underlining. This will allow you to identify the most important ideas within it. Alternatively, you might find that it is best to read a whole chapter first, to get a sense of the main ideas, then go back and highlight points that build the argument.

Make notes in the margin to highlight questions or thoughts . You can do this in both ebooks and hard copies, or use post-it notes if you do not wish to mark the book (for example, if it is a library book). This process helps you to engage better with the content, and therefore makes what you read more memorable.

Use the signposts within the text itself . Look out for phrases such as ‘crucially’ and ‘most importantly’. These highlight areas that the author(s) felt were important.

Break up your reading time with periods where you write down summaries of what you have read . You can either do this without referring back to the text, or simply use draw on the text. This will help you to focus on the most important ideas.

Asking yourself questions about the author’s intended meaning , or the effect they wished to produce. This is a process called critical reading , and there is more about this process in our page on Critical Reading .

Necessary Reading Materials

When you are engaged in formal study, for example at college or university, there will be distinct areas of reading that you will be directed towards.

These may include:

Course Materials

Course materials will vary considerably from one institution to another and also across different disciplines and for different teachers.

You may be given course materials in the form of a book, especially if you are taking a distance-learning course, or in hand-outs in lectures. Such materials may also be available online via a virtual learning environment (VLE).

You may be expected to make your own notes from lectures and seminars based around the syllabus of the course. The course materials are your main indication of what the course is about, the main topics covered and usually the assessment required. Course materials also often point you to other types of reading materials.

Core texts are the materials, usually books, journals or trusted online resources which you will be directed to via the course materials.

Core texts are essential reading, their aim is usually to expand on the subjects, discussions and arguments presented in the course materials, or through lectures etc. Remember that core texts are primarily what you will be assessed on. You will need to demonstrate comprehension of theories and ideas from these texts in your assignments.

Suggested Reading

As well as indicating core texts, reading lists may also recommend other sources of material.

Suggested reading will not only increase your comprehension of a subject area but will potentially greatly enhance the quality of your written work.

Other Sources

Perhaps one of the most important academic reading skills is to identify your own additional reading materials.

Do not just stick to what you have been told to read but expand your knowledge further by reading as much as you can around the subjects you are studying. Keep a note of everything relevant you have read, either in print or online, as you will need this information for your reference list or bibliography when producing an assignment.

See our page: Academic Referencing for more information on how to reference correctly.

Attitudes to Reading

Often, when we begin to read books relating to a new topic, we find that the language and style are difficult to follow.

This can be off-putting and disheartening, but persevere; specialist subject areas will contain their own specialist ‘language’ which you will need to learn. Perseverance will mean that you become more familiar with the style of writing and the vocabulary or jargon associated with the specific subject area.

More generally, academic writing tends to use a very cautious style or language. The writer may seem to use elaborate, long sentences, but this is usually to ensure that they are saying precisely what they mean.