How to write a PhD in a hundred steps (or more)

A workingmumscholar's journey through her phd and beyond, changing tenses as you write your dissertation.

The PhD student I am supervising sent the first draft of her methodology chapter yesterday with a series of questions and notes for me and the co-supervisor. One of them was about tense: she is writing everything in the present and future tense, but wondered if this was a mistake. It got me thinking (again) about tense in the PhD thesis , and the process of moving from future to past as the project progresses.

I have written here a little about the gap between the logic of discovery and the logic of display or dissemination in writing. As you are working, everything is either ‘I am doing this’ and ‘I will be doing that eventually’. This is pretty much the tense in which you write your proposal – proposals are forward looking. So, as you start you research, you will naturally be thinking now, and on to the next steps, and your writing will most likely reflect this in the tenses you choose. This is the logic of discovery . As you move along, you will make decisions, close some doors, open others , and your argument will unfold and form as you do so.

So what to do now, in the midst of your research and writing – can and should you anticipate being finished and therefore writing everything in the methodology in the past tense, or do you worry about that later? It does seem like more work to write in the voice of discovery while you are still discovering things, and then write again later in the voice of dissemination as you reorganise and display your thinking with the benefit of (some) hindsight. However, I would caution against trying to anticipate too much . A significant part of doing a PhD is the process of doing a piece of research, and learning through missteps, successes and issues like the one discussed here how doing and writing about research feels and looks and sounds. That way, you can go on to do further research, either on your own or with others post-PhD, and you can eventually supervise PhD students yourself.

So my advice, if you are stuck in a similar spot to my PhD student is this: be where you are . Think and write your way through this patch, and write in whatever tense and voice feels most authentic to you at this point. The good news is that there will be time for rewriting, polishing and updating before you submit, and it’s quite a pleasant feeling to go back to this methodology chapter after the findings have been presented and analysed, and find that you can edit, sharpen and focus that section to create a tight, accurate and interesting narrative about the nuts and bolts of your PhD. As you do so, every time you do so, your researcher capacity and voice and ability to add to the conversation through the knowledge you are making grows, and that is what being an academic researcher is about.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Dissertations & projects: Tenses

- Research questions

- The process of reviewing

- Project management

- Literature-based projects

On this page:

“You will use a range of tenses depending on what you are writing about . ” Elizabeth M Fisher, Richard C Thompson, and Daniel Holtom, Enjoy Writing Your Science Thesis Or Dissertation!

Tenses can be tricky to master. Even well respected journals differ in the guidance they give their authors for their use. However, their are some general conventions about what tenses are used in different parts of the report/dissertation. This page gives some advice on standard practice.

What tenses will you use?

There are exceptions however, most notably in the literature review where you will use a mixture of past , present and present perfect tenses (don't worry, that is explained below), when discussing the implications of your findings when the present tense is appropriate and in the recommendations where you are likely to use the future tense.

The tenses used as standard practice in each of these sections of your report are given and explained below.

In your abstract

You have some leeway with tense use in your abstract and guidance does vary which can sometimes be confusing. We recommend the following:

Describing the current situation and reason for your study

Mostly use the present tense, i.e. "This is the current state of affairs and this is why this study is needed."

Occasionally, you may find the need to use something called the present perfect tense when you are describing things that happened in the past but are still relevant. The present perfect tense uses have/has and then the past participle of the verb i.e. Previous research on this topic has focused on...

Describing the aims of your study

Here you have a choice. It is perfectly acceptable to use either the present or past tense, i.e. "This study aims to..." or "This study aimed to..."

Describing your methodology

Use the past tense to describe what you did, i.e. "A qualitative approach was used." "A survey was undertaken to ...". "The blood sample was analysed by..."

Describing your findings

Use the past tense to describe what you found as it is specific to your study, i.e. "The results showed that...", "The analysis indicated that..."

Suggesting the implications of your study

Use the present tense as even though your study took place in the past, your implications remain relevant in the present, i.e. Results revealed x which indicates that..."

Example abstract

An example abstract with reasoning for the tenses chosen can be found at the bottom of this excellent blog post:

Using the Present Tense and Past Tense When Writing an Abstract

In your methodology

The methodology is one of the easiest sections when it comes to tenses as you are explaining to your reader what you did. This is therefore almost exclusively written in the past tense.

Blood specimens were frozen at -80 o C.

A survey was designed using the Jisc Surveys tool.

Participants were purposefully selected.

The following search strategy was used to search the literature:

Very occasionally you may use the present tense if you are justifying a decision you have taken (as the justification is still valid, not just at the time you made the decision). For example:

Purposeful sampling was used to ensure that a range of views were included. This sampling method maximises efficiency and validity as it identifies information-rich cases and ... (Morse & Niehaus, 2009).

In your discussion/conclusion

This will primarily be written in the present tense as you are generally discussing or making conclusions about the relevance of your findings at the present time. So you may write:

The findings of this research suggest that.../are potentially important because.../could open a new avenue for further research...

There will also be times when you use the past tense , especially when referring to part of your own research or previous published research research - but this is usually followed by something in the present tense to indicate the current relevance or the future tense to indicate possible future directions:

Analysis of the survey results found most respondents were not concerned with the processes, just the outcome. This suggests that managers should focus on...

These findings mirrored those of Cheung (2020), who also found that ESL pupils failed to understand some basic yet fundamental instructions. Addressing this will help ensure...

In your introduction

The introduction generally introduces what is in the rest of your document as is therefore describing the present situation and so uses the present tense :

Chapter 3 describes the research methodology.

Depending on your discipline, your introduction may also review the literature so please also see that section below.

In your literature review

The findings of some literature may only be applicable in the specific circumstances that the research was undertaken and so need grounding to that study. Conversely, the findings of other literature may now be accepted as established knowledge. Also, you may consider the findings of older literature to be still relevant and relatively recent literature be already superseded. The tenses you write in will help to indicate a lot of this to the reader. In other words, you will use a mix of tenses in your review depending on what you are implying.

Findings only applicable in the specific circumstances

Use the past tense . For example:

In an early study, Sharkey et al. (1991) found that isoprene emissions were doubled in leaves on sunnier sides of oak and aspen trees.

Using the past tense indicates that you are not implying that isoprene emissions are always doubled on the sunnier side of the trees, just that is what was found in the Sharkey et al. study.

Findings that are still relevant or now established knowledge

Mostly use the present tense , unless the study is not recent and the authors are the subject of the sentence (which you should use very sparingly in a literature review) when you may need to use a mixture of the past and present. For example:

A narrowing of what 'graduateness' represents damages students’ abilities to thrive as they move through what will almost certainly be complex career pathways (Holmes, 2001).

Holmes (2001) argued strongly that a narrowing of what 'graduateness' represents damages students’ abilities to thrive as they move through what will almost certainly be complex career pathways

Both of these imply that you think this is still the case (although it is perhaps more strongly implied in the first example). You may also want to use some academic caution too - such as writing 'may damage' rather than the more definite 'damages'.

Presenting your results

As with your methodology, your results section should be written in the past tense . This indicates that you are accepting that the results are specific to your research. Whilst they may have current implications, that part will not be considered until your discussion/conclusions section(s).

Four main themes were identified from the interview data.

There was a significant change in oxygen levels.

Like with the methodology, you will occasionally switch to present tense to write things like "Table 3.4 shows that ..." but generally, stick to the past tense.

In your recommendations

Not everyone will need to include recommendations and some may have them as part of the conclusions chapter. Recommendations are written in a mixture of the present tense and future tense :

It is recommended that ward layout is adapted, where possible, to provide low-sensory bays for patients with autism. These will still be useable by all patients but...

Useful links

- Verb tenses in scientific manuscripts From International Science Editing

- Which Verb Tenses Should I Use in a Research Paper? Blog from WordVice

- << Previous: Writing style

- Next: Voice >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 1:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/dissertations

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

Tense tendencies in academic texts

Published on September 30, 2014 by Shane Bryson . Revised on August 9, 2024.

Different sections of academic papers ( theses , dissertations and essays ) tend to use different tenses . The following is a breakdown of these tendencies by section. Please note that while it is useful to keep these tendencies in mind, there may be exceptions. The breakdown below should help guide your writing, but keep in mind that you may have to shift tenses in any given section, depending on your topic matter.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract or summary, introduction, theoretical framework, literature review, methods and results, conclusions or discussion, limitations, recommendations and implications, other interesting articles, present simple: for facts and general truisms; to say what the paper does.

This thesis examines the ways that ecological poetry relates to political activism.

Our research suggests better economic policies.

Present perfect: for past events or research still relevant to the present

Thinkers have examined how ecological poetry relates to political activism.

Other economists have suggested different economic policies.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Present simple: to say what the paper does and why it is important

This research is relevant to how we understand the role of poetry.

Effective economic policies help societies to prosper.

Past simple: to provide historical background

In his time, Thoreau concerned himself with living in harmony with nature.

Ronald Reagan’s policies changed America’s political landscape.

Present simple: to describe theories and provide definitions

In lyric poetry, the speaker presents his perspective on a given situation.

“Reaganomics” refers to the economic policies of Reagan administration.

Present perfect: for past research still relevant to the paper’s current research

Past simple: to describe specific steps or actions of past researchers, past simple: for events that began and ended in the past, such as an experiment.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with the participants.

We found that participants had much to say about their workplaces.

A multivariate linear regression was used.

Present simple: to describe a tool’s function (which does not change over time)

Multivariate linear regressions are relevant to use for sets of correlated random variables.

Present simple: for interpretations of data

The results indicate a steady increase in net gain for x and y companies.

We cannot conclude that this growth will continue on the basis of this study.

Past simple: for details about how the study happened

The sample size was adequate for a qualitative analysis, but it was not big enough to provide good grounds for predictions.

Modal auxiliary to indicate lack of a certain outcome or simple future with hedging word: for thoughts on what future studies might focus on, and for careful predictions

Modal auxiliary : Responses to the survey suggest that many more people in this profession may be unsatisfied with their vacation time.

Modal auxiliary : Future research should conduct more sustained investigations of this phenomenon.

Simple future with hedging word : The results of the study indicate that the glaciers will likely continue to melt.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Begging the question fallacy

- Hasty generalization fallacy

- Equivocation fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bryson, S. (2024, August 08). Tense tendencies in academic texts. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/tense-tendencies/

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

"I thought AI Proofreading was useless but.."

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Dissertation & Doctoral Project Formatting & Clearance: APA Style 7th Ed.

- Submitting to the Library

- Formatting Manual & Forms

- APA Style 7th Ed.

- Submitting to ProQuest ETD

SPRING 2024 CHANGES TO THE DISSERTATION CLEARANCE PROCESS

In order to streamline the dissertation clearance process, the following changes have been made, effective 3-1-2024 .

1. The Dissertation Cataloging Form is no longer necessary.

2. The Dissertation Clearance Form is now initiated directly by the student, and only through Adobe Sign - Signed PDFs and scanned forms have been replaced by Adobe Sign.

3. Students completing dissertation clearance are no longer required to schedule a meeting with their DCR (Dissertation Clearance Representative). If they have questions about what to do, they are welcome to schedule a DCR appointment, but it is not required.

If you have questions about these changes or other aspects of the process, contact [email protected] and we will be happy to assist.

Finding It @ Your Library

General APA Style Guidelines

WRITING STYLE

Verb tense. APA style papers should be written in past or present perfect tense:

Avoid: Mojit and Novian's (2013) experiment shows that...

Allowed: Mojit and Novian's (2013) experiment showed that...

Allowed: Mojit and Novian's (2013) experiment has shown that...

Be concise and clear

- Avoid vague statements

- Present information clearly

- Eliminate unnecessary words

Style matters

- Write objectively

- Avoid poetic or flowery language

AVOIDING BIAS

Be sensitive to labels

- Avoid identifying groups by a disorder Avoid: schizophrenics Allowed: people diagnosed with schizophrenia

- Avoid outdated or inappropriate labels

- When you must label a group, try to use a term that group prefers

Gender pronouns

- Gender refers to a social role

- Sex refers to biological characteristics

What is the APA 7th Edition Publication Manual?

The 7th edition of Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association was created by the American Psychological Assocation (APA), and contains the complete guidelines on how to format material for publication and cite your research . It is a set of style rules that codifies the components of scientific writing in order to deliver concise and bias free information to the reader.

This guide provides some of the basics to keep in mind, but it doesn't replace owning or borrowing the actual Publication Manual itself. It should be on your desk by your side throughout your writing process.

APA style, 7th edition requires specific heading formatting.

For Levels 1-3, the paragraph text begins on a new line. For Levels 4-5, the paragraph text begins on the same line and continues as a paragraph.

|

|

|

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

In Section 4.2 of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.), APA (2020) states that you should use verb tenses consistently throughout your work. See a chart of when and how to use past tense (Rodriguez found) and present perfect tense (Researchers have shown) at the APA Style website .

In-Text Citation Basics

Author/Date Citation Method

APA publications use the author/date in text citation system to briefly identify sources to readers. Each in-text citation is listed alphabetically in the reference list. All in-text citations referenced in the body of work musr appear in the reference list and vice versa.

- The author-date method includes the author's surname and the the publication year. Do not include suffixes such as Jr., Esq., etc. Example : (Jones, 2009)

- The author/date method is also used with direct quotes. Another component is added in this format: (Jones, 2009, p.19)

- When multiple pages are referenced, use pp. (Jones, 2009, pp.19-21)

Variations of author/date within a sentence Here are some examples of how the author/date citation method are formatted within different parts of a sentence. Please note the author, publication date, and study are entirely fictional.

- Beginning of a sentence: Jones (2009) completed a study on the effects of dark chocolate on heart disease.

- Middle of a sentence: In 2009, Jones's study on the effects of dark chocolate and heart disease revealed...

- End of a sentence: The study revealed that participants who ate dark chocolate bars every day did not develop heart disease (Jones, 2009).

Citing works with more than one author

- One author: Jones (2009) // (Jones, 2009)

- Two authors: Ahmed and Jones (2010) // (Ahmed & Jones, 2010)

- Three or more authors: Tsai et al. (2011) // (Tsai et al., 2011)

- Group/organization author that can be abbreviated: 1st mention: National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2012) // subsequent mentions: NIH (2012)

Sample References

Journal articles

Sharifian, N., & Grühn, D. (2019). The differential impact of social participation and social support on psychological well-being: Evidence from the Wisconsin longitudinal study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development , 88 (2), 107-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415018757213

Shiraev, E. (2017). Personality theories: A global view. SAGE.

Chapter from a book

Ochs, E., & Schieffelin , B. B. (1984). Language acquisition and socialization: Three developmental stories and their implications. In R. A. Shweder & R. A. LeVine (Eds.), Culture theory: Essays on mind, self, and emotion (pp. 276 320). Cambridge University Press.

Webpage from a website

World Health Organization. (2020, June 15) . Elder abuse . https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse

View many more examples in the APA Style Manual or on the APA Style website .

- << Previous: Formatting Manual & Forms

- Next: Submitting to ProQuest ETD >>

- Last Updated: May 20, 2024 9:49 AM

- URL: https://alliant.libguides.com/LibraryClearance

How to Use Tenses within Scientific Writing

Written by: Chloe Collier

One’s tense will vary depending on what one is trying to convey within their paper or section of their paper. For example, the tense may change between the methods section and the discussion section.

Abstract --> Past tense

- The abstract is usually in the past tense due to it showing what has already been studied.

Example: “This study was conducted at the Iyarina Field School, and within the indigenous Waorani community within Yasuni National Park region.”

Introduction --> Present tense

- Example: “ Clidemia heterophylla and Piperaceae musteum are both plants with ant domata, meaning that there is an ant mutualism which protects them from a higher level of herbivory.”

Methods --> Past tense

- In the methods section one would use past tense due to what they have done was in the past.

- It has been debated whether one should use active or passive voice. The scientific journal Nature states that one should use active voice as to convey the concepts more directly.

- Example: “In the geographic areas selected for the study, ten random focal plants were selected as points for the study.”

Results --> Past tense

- Example: “We observed that there was no significant statistical difference in herbivory on Piperaceae between the two locations, Yasuni National Park, Ecuador (01° 10’ 11, 13”S and 77° 10’ 01. 47 NW) and Iyarina Field School, Ecuador (01° 02’ 35.2” S and 77° 43’ 02. 45” W), with the one exception being that there was found to be a statistical significance in the number count within a one-meter radius of Piperaceae musteum (Piperaceae).”

Discussion --> Present tense and past tense

- Example: “Symbiotic ant mutualistic relationships within species will defend their host plant since the plant provides them with food. In the case of Melastomataceae, they have swellings at the base of their petioles that house the ants and aid to protect them from herbivores.”

- One would use past tense to summarize one’s results

- Example: “In the future to further this experiment, we would expand this project and expand our sample size in order to have a more solid base for our findings.”

Verbs are direct, vigorous communicators. Use a chosen verb tense consistently throughout the same and adjacent paragraphs of a paper to ensure smooth expression.

Use the following verb tenses to report information in APA Style papers.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Literature review (or whenever discussing other researchers’ work) | Past | Martin (2020) addressed |

| Present perfect | Researchers have studied | |

| Method Description of procedure | Past | Participants took a survey |

| Present perfect | Others have used similar approaches | |

| Reporting of your own or other researchers’ results | Past | Results showed Scores decreased Hypotheses were not supported |

| Personal reactions | Past | I felt surprised |

| Present perfect | I have experienced | |

| Present | I believe | |

| Discussion of implications of results or of previous statements | Present | The results indicate The findings mean that |

| Presentation of conclusions, limitations, future directions, and so forth | Present | We conclude Limitations of the study are Future research should explore |

Verb tense is covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 4.12 and the Concise Guide Section 2.12

From the APA Style blog

Check your tone: Keeping it professional

When writing an APA Style paper, present ideas in a clear and straightforward manner. In this kind of scholarly writing, keep a professional tone.

The “no second-person” myth

Many writers believe the “no second-person” myth, which is that there is an APA Style guideline against using second-person pronouns such as “you” or “your.” On the contrary, you can use second-person pronouns in APA Style writing.

The “no first-person” myth

Whether expressing your own views or actions or the views or actions of yourself and fellow authors, use the pronouns “I” and “we.”

Navigating the not-so-hidden treasures of the APA Style website

This post links directly to APA Style topics of interest that users may not even know exist on the website.

Welcome, singular “they”

This blog post provides insight into how this change came about and provides a forum for questions and feedback.

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Grammar: Verb Tenses

Most common verb tenses in academic writing.

According to corpus research, in academic writing, the three tenses used the most often are the simple present , the simple past , and the present perfect (Biber et al., 1999; Caplan, 2012). The next most common tense for capstone writers is the future ; the doctoral study/dissertation proposal at Walden is written in this tense for a study that will be conducted in the future.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of written and spoken English . Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1162/089120101300346831

Caplan, N. A. (2012). Grammar choices for graduate and professional writers . University of Michigan Press.

Simple present: Use the simple present to describe a general truth or a habitual action. This tense indicates that the statement is generally true in the past, present, and future.

- Example: The hospital admits patients whether or not they have proof of insurance.

Simple past : Use the simple past tense to describe a completed action that took place at a specific point in the past (e.g., last year, 1 hour ago, last Sunday). In the example below, the specific point of time in the past is 1998.

- Example: Zimbardo (1998) researched many aspects of social psychology.

Present perfect: Use the present perfect to indicate an action that occurred at a nonspecific time in the past. This action has relevance in the present. The present perfect is also sometimes used to introduce background information in a paragraph. After the first sentence, the tense shifts to the simple past.

- Example: Numerous researchers have used this method.

- Example: Many researchers have studied how small business owners can be successful beyond the initial few years in business. They found common themes among the small business owners.

Future: Use the future to describe an action that will take place at a particular point in the future (at Walden, this is used especially when writing a proposal for a doctoral capstone study).

- Example: I will conduct semistructured interviews.

Keep in mind that verb tenses should be adjusted after the proposal after the research has been completed. See this blog post about Revising the Proposal for the Final Capstone Document for more information.

APA Style Guidelines on Verb Tense

APA calls for consistency and accuracy in verb tense usage (see APA 7, Section 4.12 and Table 4.1). In other words, avoid unnecessary shifts in verb tense within a paragraph or in adjacent paragraphs to help ensure smooth expression.

- Use the past tense (e.g., researchers presented ) or the present perfect (e.g., researchers have presented ) for the literature review and the description of the procedure if discussing past events.

- Use the past tense to describe the results (e.g., test scores improved significantly).

- Use the present tense to discuss implications of the results and present conclusions (e.g., the results of the study show …).

When explaining what an author or researcher wrote or did, use the past tense.

- Patterson (2012) presented, found, stated, discovered…

However, there can be a shift to the present tense if the research findings still hold true:

- King (2010) found that revising a document three times improves the final grade.

- Smith (2016) discovered that the treatment is effective.

Verb Tense Guidelines When Referring to the Document Itself

To preview what is coming in the document or to explain what is happening at that moment in the document, use the present or future tense:

- In this study, I will describe …

- In this study, I describe …

- In the next chapter, I will discuss …

- In the next chapter, I discuss …

To refer back to information already covered, such as summaries of discussions that have already taken place or conclusions to chapters/sections, use the past tense:

- Chapter 1 contained my original discussion of the research questions.

- In summary, in this section, I presented information on…

Simple Past Versus the Present Perfect

Rules for the use of the present perfect differ slightly in British and American English. Researchers have also found that among American English writers, sometimes individual preferences dictate whether the simple past or the present perfect is used. In other words, one American English writer may choose the simple past in a place where another American English writer may choose the present perfect.

Keep in mind, however, that the simple past is used for a completed action. It often is used with signal words or phrases such as "yesterday," "last week," "1 year ago," or "in 2015" to indicate the specific time in the past when the action took place.

- I went to China in 2010 .

- He completed the employee performance reviews last month .

The present perfect focuses more on an action that occurred without focusing on the specific time it happened. Note that the specific time is not given, just that the action has occurred.

- I have travelled to China.

The present perfect focuses more on the result of the action.

- He has completed the employee performance reviews.

The present perfect is often used with signal words such as "since," "already," "just," "until now," "(not) yet," "so far," "ever," "lately," or "recently."

- I have already travelled to China.

- He has recently completed the employee performance reviews.

- Researchers have used this method since it was developed.

Summary of English Verb Tenses

The 12 main tenses:

- Simple present : She writes every day.

- Present progressive: She is writing right now.

- Simple past : She wrote last night.

- Past progressive: She was writing when he called.

- Simple future : She will write tomorrow.

- Future progressive: She will be writing when you arrive.

- Present perfect : She has written Chapter 1.

- Present perfect progressive: She has been writing for 2 hours.

- Past perfect: She had written Chapter 3 before she started Chapter 4.

- Past perfect progressive: She had been writing for 2 hours before her friends arrived.

- Future perfect: She will have written Chapter 4 before she writes Chapter 5.

- Future perfect progressive: She will have been writing for 2 hours by the time her friends come over.

Conditionals:

Zero conditional (general truths/general habits).

- Example: If I have time, I write every day.

First conditional (possible or likely things in the future).

- Example: If I have time, I will write every day.

Second conditional (impossible things in the present/unlikely in the future).

- Example : If I had time, I would write every day.

Third conditional (things that did not happen in the past and their imaginary results)

- Example : If I had had time, I would have written every day.

Subjunctive : This form is sometimes used in that -clauses that are the object of certain verbs or follow certain adjectives. The form of the subjective is the simple form of the verb. It is the same for all persons and number.

- Example : I recommend that he study every day.

- Example: It is important that everyone set a writing schedule.

Verbs Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Grammar for Academic Writers: Common Verb Tenses in Academic Writing (video transcript)

- Grammar for Academic Writers: Verb Tense Consistency (video transcript)

- Grammar for Academic Writers: Advanced Subject–Verb Agreement (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Helping Verbs (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Past Tense (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Present Tense (video transcript)

- Mastering the Mechanics: Future Tense (video transcript)

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Verb Tenses

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Comparisons

- Next Page: Verb Forms: "-ing," Infinitives, and Past Participles

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advanced search

- Peter Robinson

- University of Cambridge

- Computer Laboratory

Writing a dissertation

- General information

- Innovative User Interfaces →

- Experimental Methods →

- Computer Graphics →

- Undergraduate supervisions

- MultiMedia Logic

- Student projects

- Proposing a project

- Administration

Writing a dissertation for either a final-year project or a PhD is a large task. Here are a few thoughts to help along the way.

Preparatory reading

Your dissertation should be written in English. If this is not your native language, it is important that you ask someone literate to proof read your dissertation. Your supervisor only has a limited amount of time, so it would be sensible to ask two or three literate friends to read your dissertation before giving it to your supervisor. That way, he or she will be able to concentrate on the technical content without being distracted by the style.

Incidentally, it is a good idea to make sure that one of your readers is not a specialist in your area of research. That way they can check that you have explained the technical concepts in an accessible way.

Chapter 27 of Day's book gives some useful advice on the use (and misuse) of English.

- Tense — You should normally use the present tense when referring to previously published work, and you should use the past tense when referring to your present results. The principal exception to this rule is when describing experiments undertaken by others in the past tense, even if the results that they established are described in the present tense. Results of calculations and statistical analyses should also be in the present tense. So "There are six basic emotions [Ekman, 1972]. I have written a computer program that distinguishes them in photographs of human faces."

- Voice — The active voice is usually more precise and less wordy than the passive voice. So "The system distinguished six emotions" rather than "It was found that the system could distinguish six emotions".

- Person — The general preference nowadays is to write in the first person, although there is still some debate.

- Number — When writing in the first person, use the singular or plural as appropriate. For a dissertation with one author, do not use the "editorial we" in place of "I". The use of "we" by a single author is outrageously pretentious.

- The Future Perfect Web site has some useful hints and tips on English usage.

- Formality — A dissertation is a formal document. Writing in the first person singular is preferred, but remember that you are writing a scientific document not a child's diary. Don't use informal abbreviations like "don't".

- Repetition — Say everything three times: introduce the ideas, explain them, and then give a summary. You can apply this to the whole dissertation with introductory and closing chapters, and to each chapter with introductory and closing sections. However, do not simply copy entire paragraphs. The three variants of the text serve different purposes and should be written differently.

- Sidenotes — Avoid remarks in parentheses and excessive use of footnotes. If something matters, say it in the main text. If it doesn't matter, leave it out.

- References — Citations in brackets are parenthetical remarks. Don't use them as nouns. So "Ekman [1972] identifies six basic emotions" rather than "Six basic emotions are identified in [Ekman, 1972]".

- Simple language — Convoluted sentences with multiple clauses—especially nested using stray punctuation—make it harder for the reader to follow the argument; avoid them. Short sentences are more effective at holding the reader's attention.

- Remember the difference between adjectives and adverbs. Likely is an adjective, probably is an adverb. Purists would also say that due to is an adjectival preposition and owing to is adverbial, but this distinction is now largely lost (although because of probably reads better anyway).

- Try not to use nouns as adjectives. Alas, this is a common problem in Computer Science publications. At the very least, limit the number of nouns that are strung together.

- Try not to split infinitives. It is perfectly good English, but a lot of people don't like it.

Word processing

Learn how to use your word processor effectively. This will probably be MS Word or LaTeX. In either case, make sure that you now how to include numbered figures, tables of contents, indexes, references and a bibliography efficiently. With MS Word, learn how to use styles consistently. With LaTeX, consider a WYSIWYG editor such as LyX.

Think about your house style for pages and for things like fragments of computer programs.

- © 2020 Peter Robinson Information provided by Peter Robinson

[email protected]

- English English Spanish German French Turkish

How Can You Decide on Tense Usage in Your Dissertation?

The corpus research suggests that the most often used tenses in academic writing are the simple present, the simple past, and the present perfect. Then, what comes next is the future tense.

Which tenses are most common in academic writing?

The corpus research suggests that the most often used tenses in academic writing are the simple present tense, the simple past tense, and the present perfect tense. Then, what comes next is the future tense.

Simple present tense: You can use the simple present to define a general truth or a habitual action. This tense demonstrates that what you state is usually true in the past, present, and future.

Example: Water generally boils at 100C.

Simple past : You may employ the simple past tense to call a completed action that occurred at a specific point in the past (e.g., last month, one hour ago, last Sunday). The specific point of time is 2019 in the following example.

Example: The first known COVID outbreak started in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in November 2019.

Present perfect tense: The present perfect indicates an action occurring at a nonspecific time or repeatedly in the past. However, this action has a close connection with the present time. The present perfect tense may introduce background information in a paragraph, reinforcing the main idea mentioned there. Following the first sentence, switching to the simple past is possible.

Example: Many scientists have employed this method.

Example: Many researchers have investigated how a small firm can succeed after its poor start. They gradually learned what is essential in the market.

Future tense: You may use the future tense to describe an action that will occur at a particular point in the future (It is imperative when writing a research, grant, or dissertation proposal).

Example: I will conduct the ANOVA procedure in my study’s statistical part.

APA guidelines concerning verb tenses

In its last published guideline, APA accentuated the consistency and accuracy in tense verb usage (APA 7, Section 4.12 and Table 4.1). It suggests that you must avoid unnecessary shifts in verb tense within a paragraph or adjacent paragraphs. This avoidance helps secure smooth expression and improves readability. It would be best if you used the past tense (e.g., scientists posed ) or the present perfect (e.g., researchers have concluded ) for the literature review . Thus, you must present the procedure description if you discuss past events. Nonetheless, it would help if you resorted to the past tense to describe the results (for example, ANOVA results revealed that the treatment improved food's shelf-life substantially). In discussing the implications of the results and present conclusions, you must use the present tense (i.e., our results suggest that alcohol consumption increases the accident incidence rate).

When you need to explain what an author or scientist stated or did, you must use the past tense.

Milliken (2012) reported, revealed, stated, found that…..…

Nevertheless, you can shift to the present tense if your research findings can be generalized or held in general:

Hunt (2010) revealed that revising a manuscript improves its chance of acceptance.

Kropf (2016) discovered that color is an essential trait of fresh meat.

Which tense should I use referring to my document (thesis, dissertation, research proposal, etc.)

If you wish to preview what is ahead in your text or elaborate on what is happening at that moment in your document, you must use either the present or future tense.

In this research, I will specify …

In this research, I specify …

In the last chapter, I will elaborate on …

In the last chapter, I elaborate on …

You can also refer back to already presented information, such as a synopsis of discussions that have already occurred or conclusions to your chapters or sections. Then, the tense you have to use is the past tense:

Chapter 1 contained the literature review.

In closing, in this section, I posed information on…

Should I use simple past tense or present perfect tense?

British and American English have slightly varying rules for using the present perfect tense. Scientists have also reported that individual preferences may dictate the usage of the simple past or the present perfect tense in American English. Put differently, an American English writer may opt for the simple past on specific occasions, whereas another American English writer may prefer the present perfect without apparent reasons.

However, you must note that the simple past tense denotes a completed action. Therefore, it usually employs signal words or phrases, including "yesterday," "last year," "a week ago," or "in 2020," to designate the specific time in the past when the action occurred.

I went to Greece in 2011 .

He finished the team member performance report last week .

The present perfect concentrates more on the action without accentuating the specific time it occurred. Note that the action has occurred even though the specific time is unavailable.

I have seen this movie three times .

The present perfect also concentrates more on the result of the action.

He has finished reviewing the manuscript.

You should be able to understand the usage of the present perfect with some signal words such as "since," "already," "just," "until now," "(not) yet," "so far," "ever," "lately," or "recently."

I have already finished the book on the Turkish economy.

Researchers have used this term since it was coined.

He has recently defended his Ph.D. dissertation.

If you need us to make your thesis or dissertation, contact us unhesitatingly!

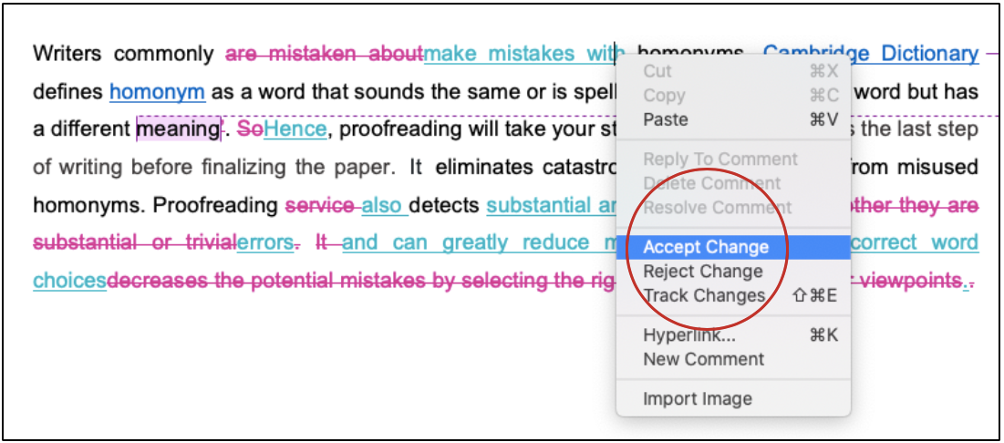

Best Edit & Proof expert editors and proofreaders focus on offering papers with proper tone, content, and style of academic writing, and also provide an upscale editing and proofreading service for you. If you consider our pieces of advice, you will witness a notable increase in the chance for your research manuscript to be accepted by the publishers. We work together as an academic writing style guide by bestowing subject-area editing and proofreading around several categorized writing styles. With the group of our expert editors, you will always find us all set to help you identify the tone and style that your manuscript needs to get a nod from the publishers.

English formatting service

You can also avail of our assistance if you are looking for editors who can format your manuscript, or just check on the particular styles for the formatting task as per the guidelines provided to you, e.g., APA, MLA, or Chicago/Turabian styles. Best Edit & Proof editors and proofreaders provide all sorts of academic writing help, including editing and proofreading services, using our user-friendly website, and a streamlined ordering process.

Get a free quote for editing and proofreading now!

Visit our order page if you want our subject-area editors or language experts to work on your manuscript to improve its tone and style and give it a perfect academic tone and style through proper editing and proofreading. The process of submitting a paper is very easy and quick. Click here to find out how it works.

Our pricing is based on the type of service you avail of here, be it editing or proofreading. We charge on the basis of the word count of your manuscript that you submit for editing and proofreading and the turnaround time it takes to get it done. If you want to get an instant price quote for your project, copy and paste your document or enter your word count into our pricing calculator.

24/7 customer support | Live support

Contact us to get support with academic editing and proofreading. We have a 24/7 active live chat mode to offer you direct support along with qualified editors to refine and furbish your manuscript.

Stay tuned for updated information about editing and proofreading services!

Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, and Medium .

For more posts, click here.

This article explains how can you dictate on tense usage in a dissertation or thesis. To give you an opportunity to practice proofreading, we have left a few spelling, punctuation, or grammatical errors in the text. See if you can spot them! If you spot the errors correctly, you will be entitled to a 10% discount.

- Editing & Proofreading

- Citation Styles

- Grammar Rules

- Academic Writing

- Proofreading

- Microsoft Tools

- Academic Publishing

- Dissertation & Thesis

- Researching

- Job & Research Application

Similar Posts

How to Determine Variability in a Dataset

Population vs Sample | Sampling Methods for a Dissertation

7 Issues to Avoid That may Dent the Quality of Thesis Writing

How to Ensure the Quality of Academic Writing in a Thesis and Dissertation?

How to Define Population and Sample in a Dissertation?

How can You Establish Experimental Design in Your Dissertation?

How Can You Write an Abstract for Your Dissertation?

How to Build Research Methods for Your Dissertation

How to Build a Strong Hypothesis for Your Dissertation

How Can You Develop Solid Research Questions for Your Dissertation?

Recent Posts

How to Determine Central Tendency

ANOVA vs MANOVA: Which Method to Use in Dissertations?

How to Specify Study Variables in Research Papers?

They Also Read

A thesis statement is the main academic argument of the thesis that distills the central idea of the study informing the readers about your stance on your thesis topic and is therefore an integral part of writing the thesis. When writing a thesis statement, there are several contentions regarding the right approach. And understandably so, for there are no definite writing rules. But there certainly are writing best practices. In this article, we will look at some of these best practices and how you can leverage them to write a formidable thesis statement. But prior to that, let’s understand what a thesis statement is.

An abstract, is an important part of an academic work and a synopsis of a longer study such as a dissertation or thesis. Its most critical aspect is precise reporting of the objectives and outcomes of your research. Thus, the readers can learn about your work by perusing your abstract.

After successfully specifying your project’s research problem, penning a problem statement pursues. Two crucial properties of an efficient problem statement are its conciseness and tangibility.

This page has been archived and is no longer being updated regularly.

Dissertation do's

Four ways to keep your capstone project on track.

By Jared C. Clark

gradPSYCH Staff

When it comes to dissertations, students make the same mistakes every term, says Lynette Bikos, PhD, psychology professor at Seattle Pacific University who sits on three dissertation committees.

Among the most common are mismanaging their time or making style flaws, she says. Chances are, such mistakes won't make or break your capstone project, but they are not going to enhance it either. Avoid the most common problems by:

Allowing enough time. "Even our best students underestimate the amount of time it takes for the faculty to review [proposals] and to get revisions together," says Bikos.

Many students think that their first proposal will get turned around in a few weeks, but dissertation chairs generally require numerous rewrites before even passing along the proposal to the rest of the committee, she notes. The committee may then require revisions or meetings before they approve your proposal.

Help keep your dissertation on track by working directly with your adviser to create a reverse calendar: Start with the proposal deadline and work backward, creating progress benchmarks along the way, advises Bikos.

Time traps can be further avoided by taking a critical look at the scope of your project, says John D. Cone, PhD, author of "Dissertations and Theses from Start to Finish" (APA, 2006). If your research project is too ambitious, you can find yourself with too much work and not enough time. "By looking at recent dissertations completed under the chair, students can get a good idea of the size of previously successful research projects," Cone says.

Picking a committee that fits your research. Students often choose committee members for reasons that do not relate directly to their dissertations, says Bikos. Dr. Doe may be your favorite professor, but if he's not an expert on your research topic, leave him off your committee. Instead, find committee members who are versed in your dissertation area, who can recommend appropriate research designs to address your proposed questions, she notes.

In addition to expertise, consider potential committee members' other commitments. "Assembling a committee that will be consistently available is important," says Cone. "Know their sabbatical plans, and when they take time off—like summers."

Writing with a narrative thread. Your dissertation should tell a story, says Bikos. All too often, students present the individual aspects of their research separately without addressing how those aspects reflect on the bigger picture. For example, when you discuss your results, remember to explain how they fill the gap in the literature you brought up in your introduction, she advises.

Students often forget the big picture when they describe the variables in their projects, says Bikos. "Students describe the first variable, describe the second variable, and describe the third variable, but they haven't told the reader why they belong together," Bikos says.

To avoid this common pitfall, don't be afraid to remind the reader of your main point, says Bikos. Also, remember to use transition sentences between sections — they force you to think about how ideas connect with one another and ease the way for your reader.

Knowing APA style. Don't let your project sink because of poorly formatted citations or other small style mistakes. "Folks make a lot of assumptions about what APA style says when they don't know it all that well," says Bikos. Consult an APA style guide frequently, especially sections on citing research.

"Starting with simple outlines that go through review and revisions are a good way to prevent small mistakes in APA style," says Cone.

Also recognize that dissertations require both past and present tense, says Bikos. Use past tense for the introduction, method and results sections; use present tense for your discussion. Additionally, feel free to use words like, "I" and "we," Bikos notes. You did all the research, after all. Take credit for it.

Letters to the Editor

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples

Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples

Published on 20 October 2022 by Shane Bryson . Revised on 11 September 2023.

Tense communicates an event’s location in time. The different tenses are identified by their associated verb forms. There are three main verb tenses: past , present , and future .

In English, each of these tenses can take four main aspects: simple , perfect , continuous (also known as progressive ), and perfect continuous . The perfect aspect is formed using the verb to have , while the continuous aspect is formed using the verb to be .

In academic writing , the most commonly used tenses are the present simple , the past simple , and the present perfect .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Tenses and their functions, when to use the present simple, when to use the past simple, when to use the present perfect, when to use other tenses.

The table below gives an overview of some of the basic functions of tenses and aspects. Tenses locate an event in time, while aspects communicate durations and relationships between events that happen at different times.

| Tense | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| used for facts, , and truths that are not affected by the passage of time | She of papers for her classes. | |

| used for events completed in the past | She the papers for all of her classes last month. | |

| used for events to be completed in the future | She papers for her classes next semester. | |

| used to describe events that began in the past and are expected to continue, or to emphasise the relevance of past events to the present moment | She papers for most of her classes, but she still has some papers left to write. | |

| used to describe events that happened prior to other events in the past | She several papers for her classes before she switched universities. | |

| used to describe events that will be completed between now and a specific point in the future | She many papers for her classes by the end of the semester. | |

| used to describe currently ongoing (usually temporary) actions | She a paper for her class. | |

| used to describe ongoing past events, often in relation to the occurrence of another event | She a paper for her class when her pencil broke. | |

| used to describe future events that are expected to continue over a period of time | She a lot of papers for her classes next year. | |

| used to describe events that started in the past and continue into the present or were recently completed, emphasising their relevance to the present moment | She a paper all night, and now she needs to get some sleep. | |

| used to describe events that began, continued, and ended in the past, emphasising their relevance to a past moment | She a paper all night, and she needed to get some sleep. | |

| used to describe events that will continue up until a point in the future, emphasising their expected duration | She this paper for three months when she hands it in. |

It can be difficult to pick the right verb tenses and use them consistently. If you struggle with verb tenses in your thesis or dissertation , you could consider using a thesis proofreading service .

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

The present simple is the most commonly used tense in academic writing, so if in doubt, this should be your default choice of tense. There are two main situations where you always need to use the present tense.

Describing facts, generalisations, and explanations

Facts that are always true do not need to be located in a specific time, so they are stated in the present simple. You might state these types of facts when giving background information in your introduction .

- The Eiffel tower is in Paris.

- Light travels faster than sound.

Similarly, theories and generalisations based on facts are expressed in the present simple.

- Average income differs by race and gender.

- Older people express less concern about the environment than younger people.

Explanations of terms, theories, and ideas should also be written in the present simple.

- Photosynthesis refers to the process by which plants convert sunlight into chemical energy.

- According to Piketty (2013), inequality grows over time in capitalist economies.

Describing the content of a text

Things that happen within the space of a text should be treated similarly to facts and generalisations.

This applies to fictional narratives in books, films, plays, etc. Use the present simple to describe the events or actions that are your main focus; other tenses can be used to mark different times within the text itself.

- In the first novel, Harry learns he is a wizard and travels to Hogwarts for the first time, finally escaping the constraints of the family that raised him.

The events in the first part of the sentence are the writer’s main focus, so they are described in the present tense. The second part uses the past tense to add extra information about something that happened prior to those events within the book.

When discussing and analyzing nonfiction, similarly, use the present simple to describe what the author does within the pages of the text ( argues , explains , demonstrates , etc).

- In The History of Sexuality , Foucault asserts that sexual identity is a modern invention.

- Paglia (1993) critiques Foucault’s theory.

This rule also applies when you are describing what you do in your own text. When summarising the research in your abstract , describing your objectives, or giving an overview of the dissertation structure in your introduction, the present simple is the best choice of tense.

- This research aims to synthesise the two theories.

- Chapter 3 explains the methodology and discusses ethical issues.

- The paper concludes with recommendations for further research.

The past simple should be used to describe completed actions and events, including steps in the research process and historical background information.

Reporting research steps

Whether you are referring to your own research or someone else’s, use the past simple to report specific steps in the research process that have been completed.

- Olden (2017) recruited 17 participants for the study.

- We transcribed and coded the interviews before analyzing the results.

The past simple is also the most appropriate choice for reporting the results of your research.

- All of the focus group participants agreed that the new version was an improvement.

- We found a positive correlation between the variables, but it was not as strong as we hypothesised .

Describing historical events

Background information about events that took place in the past should also be described in the past simple tense.

- James Joyce pioneered the modernist use of stream of consciousness.

- Donald Trump’s election in 2016 contradicted the predictions of commentators.

The present perfect is used mainly to describe past research that took place over an unspecified time period. You can also use it to create a connection between the findings of past research and your own work.

Summarising previous work

When summarising a whole body of research or describing the history of an ongoing debate, use the present perfect.

- Many researchers have investigated the effects of poverty on health.

- Studies have shown a link between cancer and red meat consumption.

- Identity politics has been a topic of heated debate since the 1960s.

- The problem of free will has vexed philosophers for centuries.

Similarly, when mentioning research that took place over an unspecified time period in the past (as opposed to a specific step or outcome of that research), use the present perfect instead of the past tense.

- Green et al. have conducted extensive research on the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction.

Emphasising the present relevance of previous work

When describing the outcomes of past research with verbs like fi nd , discover or demonstrate , you can use either the past simple or the present perfect.

The present perfect is a good choice to emphasise the continuing relevance of a piece of research and its consequences for your own work. It implies that the current research will build on, follow from, or respond to what previous researchers have done.

- Smith (2015) has found that younger drivers are involved in more traffic accidents than older drivers, but more research is required to make effective policy recommendations.

- As Monbiot (2013) has shown , ecological change is closely linked to social and political processes.

Note, however, that the facts and generalisations that emerge from past research are reported in the present simple.

While the above are the most commonly used tenses in academic writing, there are many cases where you’ll use other tenses to make distinctions between times.

Future simple

The future simple is used for making predictions or stating intentions. You can use it in a research proposal to describe what you intend to do.

It is also sometimes used for making predictions and stating hypotheses . Take care, though, to avoid making statements about the future that imply a high level of certainty. It’s often a better choice to use other verbs like expect , predict, and assume to make more cautious statements.

- There will be a strong positive correlation.

- We expect to find a strong positive correlation.

- H1 predicts a strong positive correlation.

Similarly, when discussing the future implications of your research, rather than making statements with will, try to use other verbs or modal verbs that imply possibility ( can , could , may , might ).

- These findings will influence future approaches to the topic.

- These findings could influence future approaches to the topic.

Present, past, and future continuous

The continuous aspect is not commonly used in academic writing. It tends to convey an informal tone, and in most cases, the present simple or present perfect is a better choice.

- Some scholars are suggesting that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

- Some scholars suggest that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

- Some scholars have suggested that mainstream economic paradigms are no longer adequate.

However, in certain types of academic writing, such as literary and historical studies, the continuous aspect might be used in narrative descriptions or accounts of past events. It is often useful for positioning events in relation to one another.

- While Harry is traveling to Hogwarts for the first time, he meets many of the characters who will become central to the narrative.

- The country was still recovering from the recession when Donald Trump was elected.

Past perfect

Similarly, the past perfect is not commonly used, except in disciplines that require making fine distinctions between different points in the past or different points in a narrative’s plot.

Sources for this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Bryson, S. (2023, September 11). Verb Tenses in Academic Writing | Rules, Differences & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/english-language/verb-tenses/

Aarts, B. (2011). Oxford modern English grammar . Oxford University Press.

Butterfield, J. (Ed.). (2015). Fowler’s dictionary of modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. A. (2016). Garner’s modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

Subject-verb agreement | examples, rules & use, english mistakes commonly made in a dissertation | examples.

Magnum Proofreading Services

- Jake Magnum

- Mar 17, 2021

Using the Present Tense and Past Tense When Writing an Abstract

Updated: Jul 5, 2021

In general, when writing an abstract, you should use the simple present tense when stating facts and explaining the implications of your results. Use the simple past tense when describing your methodology and specific findings from your study. Either of these two tenses can be used when writing about the purpose of your study. Finally, you can use the present perfect tense or the present perfect progressive tense when explaining the background or rationale of your study.

Determining which tense to use when writing an abstract is not always straightforward. For example, even though your research was carried out in the past, some aspects of your work need to be referred to using the present tense. The purpose of this article is to teach you when to use which of four different tenses (i.e., the simple present tense, the simple past tense, the present perfect tense, and the present perfect progressive tense) when writing an abstract for a research paper.

When to Use the Simple Present Tense

The simple present tense of a verb is used for two purposes. The first is to describe something that is happening right now (e.g., “I see a bird”). The second is to explain a habitual action — that is, an action that one performs regularly, though they might not be doing it at this very moment (e.g., “I sleep for eight hours every night”).

When writing an abstract, the simple present tense is used for three main purposes: (i) to state facts, (ii) to explain the implications of your findings, and (iii) to mention the aim of your research (the simple past tense can also be used for this last purpose).

When stating facts

You will usually use the simple present tense to refer to facts since they will be just as true at the time of writing as they were when your study was being carried out. Exceptions arise if a fact is explicitly linked to some point in the past.

Indoor nighttime light exposure influences sleep and circadian rhythms.

Here, the author is making a general statement based on previous research in their field. Broad statements like this one are based on very extensive research, and so researchers assume such statements to be factual. Thus, they should be mentioned in the simple present tense.

China, whose estimated population was 1,433,783,686 at the end of 2019, is the most populated country in the world.

The author shifts from the past tense to the present tense because the first fact is explicitly linked to a point in the past (the end of 2019). Because populations change by the second, the author cannot assume the figure given is still accurate, and so they refer to this figure using the past tense. Differently, the author can reasonably assume that China still has the world’s largest population at the time of writing. Thus, this statement is written in the present tense.

When explaining the implications of your findings

You should discuss the implications of your study in the present tense. Although your research was conducted in the past, its implications remain relevant in the present.

To give an example, although the United States Declaration of Independence was adopted centuries ago, it is still in effect today, and so general statements about it are usually written in the present tense (e.g., “The US Declaration of Independence describes principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted”).

In the same way, because your research is still relevant at the time of writing, general statements about its implications should be written using the present tense as well.

Results revealed that adolescents with depression experience difficulties with sleep quality.

Here, the author starts by using the past tense because the results were produced in the past. However, because the implication of the results remains true at the time of writing, the author switches to the present tense. While it would be acceptable for the author to use the present tense of “reveal” in this sentence, it would not be okay for them to use the past tense of “experience” unless they were referring to a specific result from their study.

When describing the aim of your study

For the same reason that you should write about your study’s implications in the present tense, you can also write about the purpose of your study in the present tense. However, this rule is flexible, and it is very common for authors to write about such information in the past tense.

In this study, we explore the link between the homeostatic regulation of neuronal excitability and sleep behavior in the circadian circuit.

In this study, we explored the link between the homeostatic regulation of neuronal excitability and sleep behavior in the circadian circuit.

Both of these examples are perfectly fine. You should check your journal’s guidelines or papers that have been published in the journal to determine which tense you should use for these kinds of sentences.

When to Use the Simple Past Tense

The simple past tense of a verb is used when discussing something that happened in the past and is not still occurring (e.g., “I ate cereal this morning”).

As seen in the previous section, the simple past tense can be used to explain the purpose of your study. It should also be used when describing specific aspects of your research, such as its method and findings.

When describing your methodology and findings

Because your method has been completed at the time of writing, you should write about your method in the past tense. Similarly, because you have finished analyzing your data to obtain your findings, they should also be expressed in the past tense.

Thirty-four older people meeting DSM-IV criteria for lifetime major depression and 30 healthy controls were recruited.

Like any aspect related to methodology, the recruiting process started and finished well before the time of writing. As such, it is standard for this information to be described using the past tense.

Individuals with depression had longer sleep latency and latency to rapid eye movement sleep than controls.

Here, the author is referring to their study’s participants (this is clear because “controls” are mentioned). Since the participants have finished taking part in the study at the time of writing, this result is described in the past tense.

Results revealed that the adolescents with depression who participated in our study experienced difficulties with sleep quality.

This example is very similar to an example given in the previous section of this article (“Results revealed that adolescents with depression experience difficulties with sleep quality”). In the previous example, the present tense of “experience” was used because the author was making a broad statement about adolescents in general. Conversely, in the current example, the author is mentioning a specific result from their study. Because the study is over, the author used the past tense.

When to Use the Present Perfect (Progressive) Tense

When writing an abstract, you might sometimes need to use the present perfect tense (e.g., “Research on this topic has increased “) or the present perfect progressive tense (e.g., “Research on this topic has been increasing “) of verbs. These verb tenses are used to describe an action or situation that began in the past and that is still occurring in the present. The former tends to be used when the starting point of the action is vague, whereas the latter is often used when the starting point is mentioned (this rule is flexible, though).

A further difference between the two is that the present perfect tense — but not the present perfect progressive tense — can also be used to describe an action or situation that has been completed at some non-specific time in the past (e.g., “I have finished writing my paper”).

While these verb tenses are not used as often in abstracts as the tenses discussed previously (sometimes, they are not used at all), you can use them to describe situations or events related to the background of your study.

When describing the background of your study