5 Steps to Master College-Level Reading

Before entering college, I imagined a lot of my time would be spent in a dimly lit library, engrossed in textbooks until the late hours of the night. My high school teachers had forewarned us about the overwhelming amount of reading we would encounter in college, and popular media often reinforced this notion. And there were instances when I needed to find a quiet spot and create a strategy to move quickly and efficiently through a reading assignment. What I learned was that I needed to change my approach and build effective reading skills to meet the demands of college courses . I was able to do this by being more intentional with my assignments—and you can, too.

Here are some steps you can take to become an efficient reader and stay on top of college reading assignments:

Determine the goal of the assignment.

First, consider why the professor assigned this reading. Will you be discussing the material in class, taking a test, or writing a paper? This will help you determine what you need to get out of the reading and focus on important content to achieve your goal.

Create a quiet, ideal reading environment.

Try to choose a comfortable spot, free from distractions. I know that at times, noise is unavoidable, especially if you live in a shared space like a dorm . In that case, pop in some headphones and find tranquil sounds or music that can help drown out the background noise. I can concentrate in almost any environment if I listen to the “Pride and Prejudice” movie soundtrack or a movie score playlist. Find what works for you.

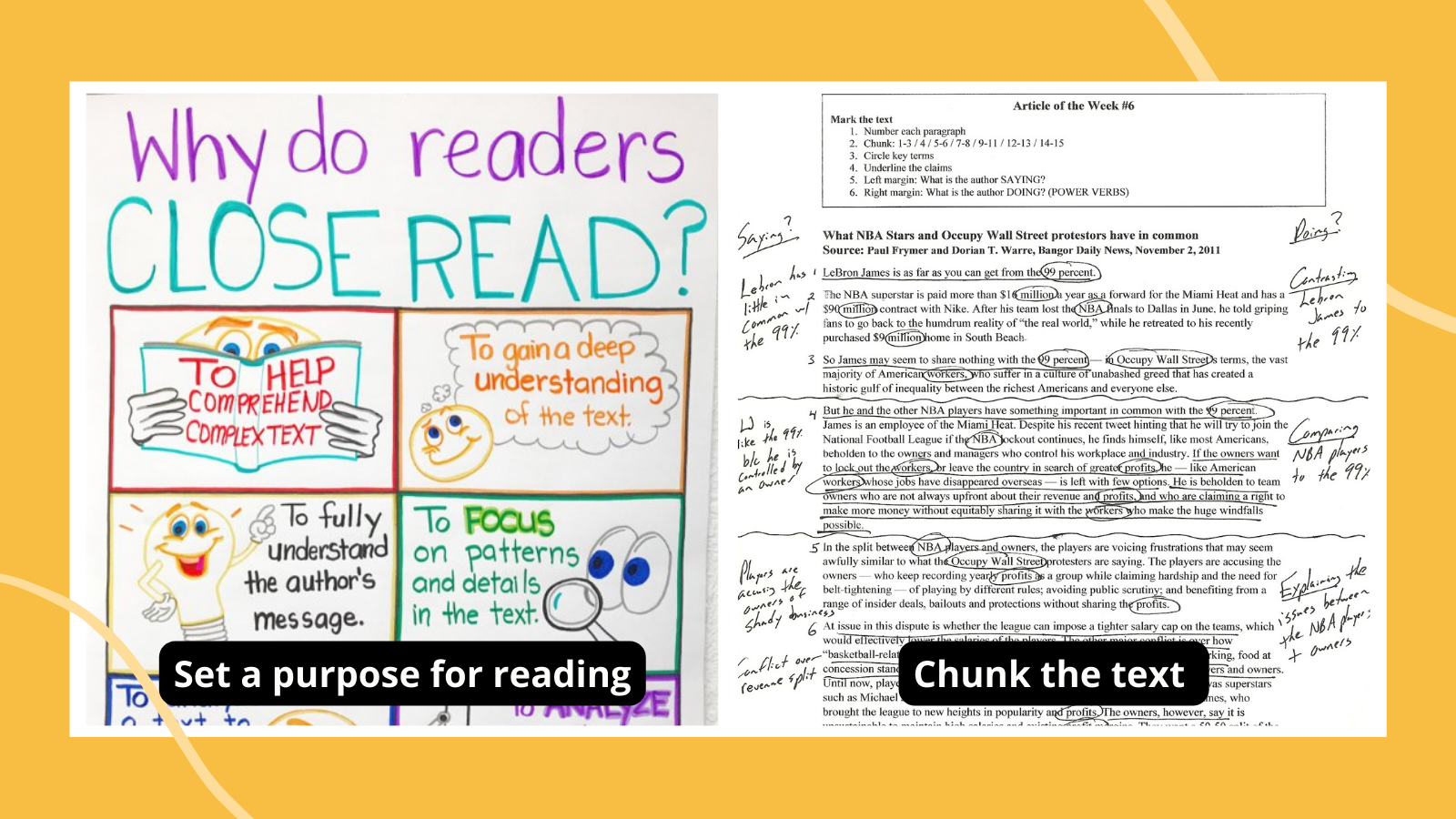

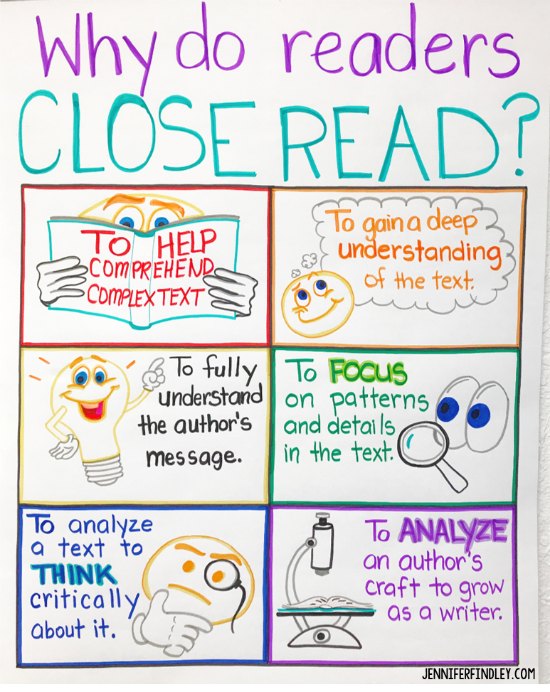

Use the SQ3R method.

SQ3R is a reading technique that works well for textbooks and research articles. The purpose is to identify what you don’t know and build on pre-existing knowledge that you already have. Here’s how you use the SQ3R method:

- Survey: Get a firm grasp on what the material is about before you start reading. Read all the titles and headlines, skim the introduction and conclusion of each section, and look at any charts, graphs, or other visuals. Some textbooks list chapter highlights—be sure to read these as well.

- Question: Break the content down into two sections—what you already understand without reading and brand-new material that you don’t fully understand. Then, write out questions about unfamiliar content to help guide your focus as you read. Your goal is to find the answers to these questions by the time you finish reading.

- Read: As you read, you want to focus on answering your questions. This does not mean intensely reading line by line, but actively searching for answers. Take notes or highlight important content as you go.

- Recite: In your own words, recite the answers to your questions and then write them down. If you struggle doing this, spend more time reading to find the answers. It might help to do this in sections throughout your reading.

- Review: Look back at your notes, highlighted content, and answers to your questions to get an overarching view of what you learned. Go through each section of the reading and check your memory and understanding by reciting the major points of each section.

Use time management.

Everyone reads at a different pace. To avoid feeling overwhelmed and rushed, look at how much reading you’ve been assigned and determine how much time you might need. Factor in time for breaks, if possible.

The transition from high school to college reading assignments can seem daunting at first, but using these tips will help you develop effective and efficient reading habits. And remember, reading is a skill. The more you practice, the better you’ll be at reading and comprehension. So, go find a good book and start practicing, and check out more tips on reading on the K12 Leading with Literacy hub.

For more helpful tips and resources that’ll get you ready for college, visit the K12 Career and College Prep page.

Related Articles

Navigating Your Pre-K Options: Public, Private, or Virtual

September 9 2024

Helping Your Teen Craft Their First Resume: A Parent’s Guide

Six Ways Online Learning Transforms the Academic Journey

September 5 2024

Encouraging Kids to Love Writing: Fun Activities to Spark Creativity

September 3 2024

A High School Senior’s Checklist for a Great Year

September 2 2024

Turn Up the Music: The Benefits of Music in Classrooms

August 27 2024

How to Create a Bully-Free Zone

A Parent’s Guide to Managing and Reducing Student Stress

August 26 2024

Protecting Your Child from Bullying: Signs, Solutions, and the Role of Online Schools

QUIZ: 20 Fun Trivia Facts to Celebrate Culture and Diversity

August 20 2024

15 Must-Read Books this Hispanic Heritage Month

August 19 2024

5 Factors That Affect Learning: Insights for Parents

August 12 2024

Navigating the College Application Process: A Timeline for High School Students and Their Parents

Education Online? One Family’s Success Story

August 7 2024

Esports vs. Traditional Sports: Exploring Their Surprising Similarities and Key Differences

August 5 2024

Tips for Choosing the Right School for Your Child

Can Homeschooled Students Play School Sports?

August 2 2024

What is Esports and Why Should My Child Participate?

July 23 2024

Enhance Your Student-Athlete’s Competitive Edge with Online Schooling

July 22 2024

Preparing for the First Day of Online School

July 12 2024

Why Arts Education is Important in School

Online School Reviews: What People Are Saying About Online School

Smart Classrooms, Smart Kids: How AI is Changing Education

Everyone Wins When Parents Get Involved In Their Child’s Education

July 11 2024

5 Ways to Start the School Year with Confidence

July 8 2024

Top Four Reasons Families Are Choosing Online School in the Upcoming Year

Tips for Scheduling Your Online School Day

July 2 2024

Life After High School: Online School Prepares Your Child For The Future

The Ultimate Back-to-School List for Online and Traditional School

July 1 2024

Nurturing Digital Literacy in Today’s Kids: A Parent’s Guide

June 25 2024

What Public Schools Can Do About Special Education Teacher Shortages

June 24 2024

Audiobooks for Kids: Benefits, Free Downloads, and More

7 Fun Outdoor Summer Activities for Kids

June 18 2024

Beat the Summer Slide: Tips for Keeping Young Minds Active

June 11 2024

How to Encourage Your Child To Pursue a Career

Easy Science Experiments For Kids To Do At Home This Summer

May 31 2024

4 Ways to Get Healthcare Experience in High School

May 29 2024

5 Strategies for Keeping Students Engaged in Online Learning

May 21 2024

How Parents Can Prevent Isolation and Loneliness During Summer Break

May 14 2024

The Ultimate Guide to Gift Ideas for Teachers

How to Thank a Teacher: Heartfelt Gestures They Won’t Forget

Six Ways Online Schools Can Support Military Families

7 Things Teachers Should Know About Your Child

April 30 2024

Countdown to Graduation: How to Prepare for the Big Day

April 23 2024

How am I Going to Pay for College?

April 16 2024

5 Major Benefits of Summer School

April 12 2024

Inspiring an Appreciation for Poetry in Kids

April 9 2024

A Parent’s Guide to Tough Conversations

April 2 2024

The Importance of Reading to Children and Its Enhancements to Their Development

March 26 2024

March 19 2024

10 Timeless Stories to Inspire Your Reader: Elementary, Middle, and High Schoolers

March 15 2024

From Books to Tech: Why Libraries Are Still Important in the Digital Age

March 13 2024

The Evolution of Learning: How Education is Transforming for Future Generations

March 11 2024

The Ultimate Guide to Reading Month: 4 Top Reading Activities for Kids

March 1 2024

Make Learning Fun: The 10 Best Educational YouTube Channels for Kids

February 27 2024

The Value of Soft Skills for Students in the Age of AI

February 20 2024

30 Questions to Ask at Your Next Parent-Teacher Conference

February 6 2024

Four Life Skills to Teach Teenagers for Strong Resumes

January 25 2024

Exploring the Social Side of Online School: Fun Activities and Social Opportunities Await

January 9 2024

Is Your Child Ready for Advanced Learning? Discover Your Options.

January 8 2024

Your Ultimate Guide to Holiday Fun and Activities

December 18 2023

Free Printable Holiday Coloring Pages to Inspire Your Child’s Inner Artist

December 12 2023

Five Reasons to Switch Schools Midyear

December 5 2023

A Parent’s Guide to Switching Schools Midyear

November 29 2023

Building Strong Study Habits: Back-to-School Edition

November 17 2023

A Parent’s Guide to Robotics for Kids

November 6 2023

How to Get Ahead of Cyberbullying

October 30 2023

Bullying’s Effect on Students and How to Help

October 25 2023

Can You Spot the Warning Signs of Bullying?

October 16 2023

Could the Online Classroom Be the Solution to Bullying?

October 11 2023

Bullying Prevention Starts With Parents

October 9 2023

Six Tips for Choosing a College Major

August 23 2023

Six Tips For Keeping Up With College Deadlines

September 5 2023

Planning for College: Advice from a College Admissions Expert

December 11 2013

30 Books to Add to Your Reading List in High School

January 1 2014

Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and join America’s premier community dedicated to helping students reach their full potential.

Welcome! Subscribe to our newsletter and join America’s premier community dedicated to helping students reach their full potential.

- Instructors

- Institutions

- Teaching Strategies

- Higher Ed Trends

- Academic Leadership

- Affordability

- Product Updates

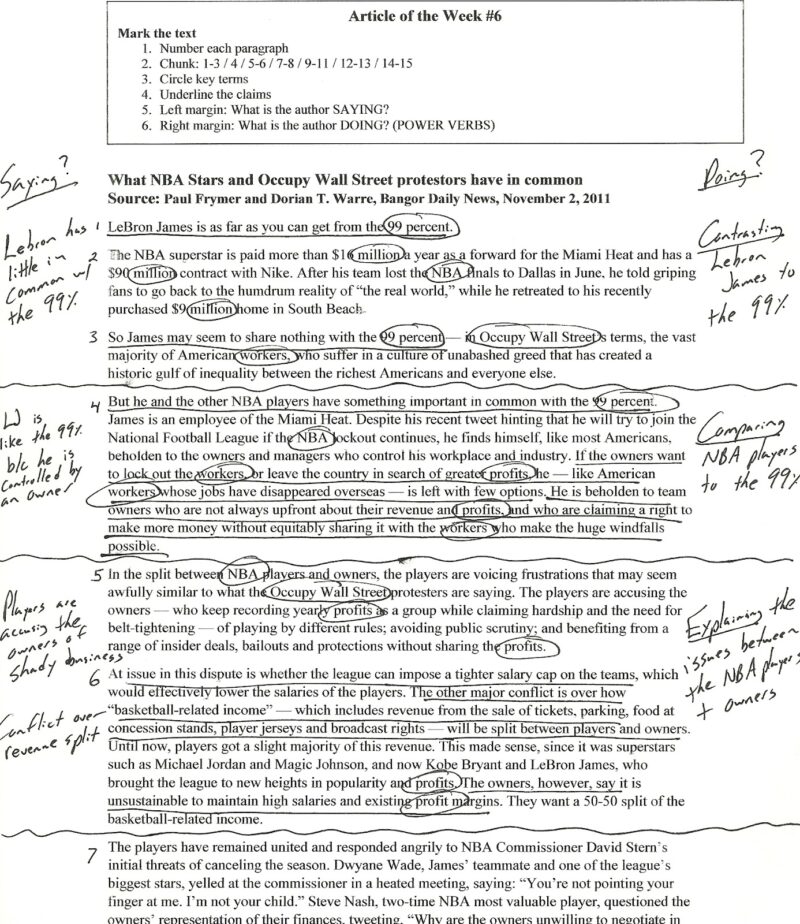

4 Ways to Get Your Students to Do the Assigned Reading

Dr. Jenny Billings is a faculty member at Rowan-Cabarrus Community College.

Students do not always complete assigned readings. This is true for chapters, novels, articles, or even single poems. Being an English instructor, I take this personally. I laugh while writing this, but it’s true! When I craft my course, I am constantly considering which format will give my students everything they need to be successful. I tell my babies, “I have given you the world. Together, we can decide how best to navigate it.” I have always been the kind of instructor to select the assigned chapters first, then build the rest of the course around them. These chapters are presented in a certain order to help dictate the rest of the “world” I build for my students: the corresponding notes, what I lecture on, the videos I embed, the assignments they complete, and the discussion questions they consider. With the chapters bearing so much weight, what if my students opt out of reading? Here are four ways I get my students to read what I assign. Hopefully, they’ll help you, too.

1. Start Small: Change Your Approach

I used to get so frustrated when a student would ask me a question that was addressed in the reading I had just assigned. I’d often ask or write back, “Did you read Chapter X in your eTextbook?” The student would respond one of two ways: 1) “No (but I will)” or 2) “Yes, I read it (but don’t understand what it said).” The question I asked prompted these responses only; I wasn’t allowing for anything else.

I’ve changed the way I approach this. Instead of putting the sole responsibility back on the student—”Have you read the chapter?”—I create an opportunity for us to navigate the reading together. Instead, I’ll ask, “What section, page, or concept tripped you up?” From there, we narrow it down, discuss it together, and the student walks away with a better understanding. Even if it was only that portion, and even if they didn’t really read the chapter to begin with, they now grasp that concept or section. That’s still a win in my book. You know what else is a win? The fact that they are more likely to read in the future because I didn’t turn them away.

2. Less Assigned Reading is More. Seriously.

Our students are drowning in information daily. Social media, the news, their home life, their work life, their families, their kids … these things combined lead to information overload. Our students are coming to us for an education, sure, but they are also coming to us for change.

I’m not saying that you must remove important information from your class. I’m saying that you need to evaluate how much reading you’re assigning. You and I both know that there are concepts, pages, and even chapters that can be omitted and replaced with a video or live lecture. When I started teaching high school, I taught the same way I was taught. I assigned reading outside of class and then once back in class, I went over what students were supposed to read outside of class. See the redundancy? If I’m going to go over it anyway, why would the students need to read it beforehand? Rather than go over it, the in-class session should be an expansion of what they read. They should apply what they read to class, the assignment, etc. in a way that requires them to read to do well. For them to recall everything that they’ve read, especially on the spot, you need to assign less reading. Like Theresa MacPhail says, “My students are getting the information—but in the formats with which they are most comfortable.”

3. Assigned Reading Should Be Relevant

I’m guilty of assigning reading because I felt it was “easier” for students to get the information that way. If students aren’t reading, they aren’t getting the information. If the reading you assigned isn’t relevant to the assignment they’re focused on in that moment, you’ve lost them.

The reading can’t be relevant just to the course—or just to the final exam. Assign reading quizzes consistently. Use your LMS or digital platform dashboard to gauge reading and student engagement. Set the expectation that all students will participate in class discussions—and stick to it! The assigned reading must be understood and utilized immediately to establish relevancy, and thus, importance in the minds of students. Don’t believe me? I asked my babies how they defined relevant reading and reading they were more likely to complete. Here are some direct quotes:

“If I know that the chapter assigned will show me how to do the current assignment, I’m much more likely to read it. Well, skim it efficiently.”

“When you tell us the pages that will help us the most with our assignment, I always read and use those.”

“Relevant reading assignments are those that provide insight on how I can be successful on the essay you just assigned. Almost like they are telling me a secret that I would have missed otherwise.”

See what I mean? Students know what they need to read. They’ll also tell you, honestly, how to entice them to read. So, ask.

4. Don’t Assign Reading Just for Reading’s Sake

According to Linda B. Nilson , students “only spend about 37% of their reading time on college reading assignments, which they describe as ‘tedious’ and ‘time-consuming.’ In fact, they often skip the assigned readings unless their grades depend on it.” If you’re assigning reading as an assignment, ensure there’s a grade associated with it. The days of assigning reading so students “can apply concepts later” are gone. It’s not difficult to make sure that graded work is directly related to what students were supposed to read and assigned in a timely manner.

I would also encourage you to give your students assignments that serve as chapter maps. Give them in advance so students know what to focus on and what to read specifically. Then ask them to apply those concepts critically to the assignment. Students are more likely to read what you assign if you tell them: 1) exactly what to read, 2) where that information will be used (i.e., on what assignment), 3) how the reading applies to their current assignment or work, and 4) what they’re risking by not completing the reading. Students are grade-driven; success should be reading-driven.

We know there are plenty of barriers to reading . Students are not exactly pining to read academic text, especially if it’s extensive and dry. Getting students to read starts with selecting the right texts. I have worked at this for almost 10 years. In the current remote setting I find myself in, getting students to embrace all I provide them is even more important to their success. The worry that students are reading less has grown every year and will continue to do so. Instead of worrying that students are reading less, perhaps we can focus on assigning less and seeing more success.

Looking to do more reading yourself? Check out our brand new Anti-Racist Reading List, where we compiled recommendations from your peers!

Related articles.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 Reading and Writing in College

Learning objectives.

- Understand the expectations for reading and writing assignments in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies to complete college-level reading assignments efficiently and effectively.

- Recognize specific types of writing assignments frequently included in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies for managing college-level writing assignments.

- Determine specific reading and writing strategies that work best for you individually.

As you begin this chapter, you may be wondering why you need an introduction. After all, you have been writing and reading since elementary school. You completed numerous assessments of your reading and writing skills in high school and as part of your application process for college. You may write on the job, too. Why is a college writing course even necessary?

When you are eager to get started on the coursework in your major that will prepare you for your career, getting excited about an introductory college writing course can be difficult. However, regardless of your field of study, honing your writing skills—and your reading and critical-thinking skills—gives you a more solid academic foundation.

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work you are expected to do is increased. When instructors expect you to read pages upon pages or study hours and hours for one particular course, managing your work load can be challenging. This chapter includes strategies for studying efficiently and managing your time.

The quality of the work you do also changes. It is not enough to understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will also be expected to seriously engage with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about a given subject. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. A good introductory writing course will help you swim.

Table 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” summarizes some of the other major differences between high school and college assignments.

Table 1.1 High School versus College Assignments

| High School | College |

|---|---|

| Reading assignments are moderately long. Teachers may set aside some class time for reading and reviewing the material in depth. | Some reading assignments may be very long. You will be expected to come to class with a basic understanding of the material. |

| Teachers often provide study guides and other aids to help you prepare for exams. | Reviewing for exams is primarily your responsibility. |

| Your grade is determined by your performance on a wide variety of assessments, including minor and major assignments. Not all assessments are writing based. | Your grade may depend on just a few major assessments. Most assessments are writing based. |

| Writing assignments include personal writing and creative writing in addition to expository writing. | Outside of creative writing courses, most writing assignments are expository. |

| The structure and format of writing assignments is generally stable over a four-year period. | Depending on the course, you may be asked to master new forms of writing and follow standards within a particular professional field. |

| Teachers often go out of their way to identify and try to help students who are performing poorly on exams, missing classes, not turning in assignments, or just struggling with the course. Often teachers will give students many “second chances.” | Although teachers want their students to succeed, they may not always realize when students are struggling. They also expect you to be proactive and take steps to help yourself. “Second chances” are less common. |

This chapter covers the types of reading and writing assignments you will encounter as a college student. You will also learn a variety of strategies for mastering these new challenges—and becoming a more confident student and writer.

Throughout this chapter, you will follow a first-year student named Crystal. After several years of working as a saleswoman in a department store, Crystal has decided to pursue a degree in elementary education and become a teacher. She is continuing to work part-time, and occasionally she finds it challenging to balance the demands of work, school, and caring for her four-year-old son. As you read about Crystal, think about how you can use her experience to get the most out of your own college experience.

Review Table 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” and think about how you have found your college experience to be different from high school so far. Respond to the following questions:

- In what ways do you think college will be more rewarding for you as a learner?

- What aspects of college do you expect to find most challenging?

- What changes do you think you might have to make in your life to ensure your success in college?

Reading Strategies

Your college courses will sharpen both your reading and your writing skills. Most of your writing assignments—from brief response papers to in-depth research projects—will depend on your understanding of course reading assignments or related readings you do on your own. And it is difficult, if not impossible, to write effectively about a text that you have not understood. Even when you do understand the reading, it can be hard to write about it if you do not feel personally engaged with the ideas discussed.

This section discusses strategies you can use to get the most out of your college reading assignments. These strategies fall into three broad categories:

- Planning strategies. To help you manage your reading assignments.

- Comprehension strategies. To help you understand the material.

- Active reading strategies. To take your understanding to a higher and deeper level.

Planning Your Reading

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam? Or found yourself skimming a detailed memo from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? The first step in handling college reading successfully is planning. This involves both managing your time and setting a clear purpose for your reading.

Managing Your Reading Time

You will learn more detailed strategies for time management in Section 1.2 “Developing Study Skills” , but for now, focus on setting aside enough time for reading and breaking your assignments into manageable chunks. If you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, try not to wait until the night before to get started. Give yourself at least a few days and tackle one section at a time.

Your method for breaking up the assignment will depend on the type of reading. If the text is very dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, you may need to read no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you will be able to handle longer sections—twenty to forty pages, for instance. And if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

As the semester progresses, you will develop a better sense of how much time you need to allow for the reading assignments in different subjects. It also makes sense to preview each assignment well in advance to assess its difficulty level and to determine how much reading time to set aside.

College instructors often set aside reserve readings for a particular course. These consist of articles, book chapters, or other texts that are not part of the primary course textbook. Copies of reserve readings are available through the university library; in print; or, more often, online. When you are assigned a reserve reading, download it ahead of time (and let your instructor know if you have trouble accessing it). Skim through it to get a rough idea of how much time you will need to read the assignment in full.

Setting a Purpose

The other key component of planning is setting a purpose. Knowing what you want to get out of a reading assignment helps you determine how to approach it and how much time to spend on it. It also helps you stay focused during those occasional moments when it is late, you are tired, and relaxing in front of the television sounds far more appealing than curling up with a stack of journal articles.

Sometimes your purpose is simple. You might just need to understand the reading material well enough to discuss it intelligently in class the next day. However, your purpose will often go beyond that. For instance, you might also read to compare two texts, to formulate a personal response to a text, or to gather ideas for future research. Here are some questions to ask to help determine your purpose:

How did my instructor frame the assignment? Often your instructors will tell you what they expect you to get out of the reading:

- Read Chapter 2 and come to class prepared to discuss current teaching practices in elementary math.

- Read these two articles and compare Smith’s and Jones’s perspectives on the 2010 health care reform bill.

- Read Chapter 5 and think about how you could apply these guidelines to running your own business.

- How deeply do I need to understand the reading? If you are majoring in computer science and you are assigned to read Chapter 1, “Introduction to Computer Science,” it is safe to assume the chapter presents fundamental concepts that you will be expected to master. However, for some reading assignments, you may be expected to form a general understanding but not necessarily master the content. Again, pay attention to how your instructor presents the assignment.

- How does this assignment relate to other course readings or to concepts discussed in class? Your instructor may make some of these connections explicitly, but if not, try to draw connections on your own. (Needless to say, it helps to take detailed notes both when in class and when you read.)

- How might I use this text again in the future? If you are assigned to read about a topic that has always interested you, your reading assignment might help you develop ideas for a future research paper. Some reading assignments provide valuable tips or summaries worth bookmarking for future reference. Think about what you can take from the reading that will stay with you.

Improving Your Comprehension

You have blocked out time for your reading assignments and set a purpose for reading. Now comes the challenge: making sure you actually understand all the information you are expected to process. Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer or more complex, so you will need a plan for how to handle them.

For any expository writing —that is, nonfiction, informational writing—your first comprehension goal is to identify the main points and relate any details to those main points. Because college-level texts can be challenging, you will also need to monitor your reading comprehension. That is, you will need to stop periodically and assess how well you understand what you are reading. Finally, you can improve comprehension by taking time to determine which strategies work best for you and putting those strategies into practice.

Identifying the Main Points

In college, you will read a wide variety of materials, including the following:

- Textbooks. These usually include summaries, glossaries, comprehension questions, and other study aids.

- Nonfiction trade books. These are less likely to include the study features found in textbooks.

- Popular magazine, newspaper, or web articles. These are usually written for a general audience.

- Scholarly books and journal articles. These are written for an audience of specialists in a given field.

Regardless of what type of expository text you are assigned to read, your primary comprehension goal is to identify the main point : the most important idea that the writer wants to communicate and often states early on. Finding the main point gives you a framework to organize the details presented in the reading and relate the reading to concepts you learned in class or through other reading assignments. After identifying the main point, you will find the supporting points , the details, facts, and explanations that develop and clarify the main point.

Some texts make that task relatively easy. Textbooks, for instance, include the aforementioned features as well as headings and subheadings intended to make it easier for students to identify core concepts. Graphic features, such as sidebars, diagrams, and charts, help students understand complex information and distinguish between essential and inessential points. When you are assigned to read from a textbook, be sure to use available comprehension aids to help you identify the main points.

Trade books and popular articles may not be written specifically for an educational purpose; nevertheless, they also include features that can help you identify the main ideas. These features include the following:

- Trade books. Many trade books include an introduction that presents the writer’s main ideas and purpose for writing. Reading chapter titles (and any subtitles within the chapter) will help you get a broad sense of what is covered. It also helps to read the beginning and ending paragraphs of a chapter closely. These paragraphs often sum up the main ideas presented.

- Popular articles. Reading the headings and introductory paragraphs carefully is crucial. In magazine articles, these features (along with the closing paragraphs) present the main concepts. Hard news articles in newspapers present the gist of the news story in the lead paragraph, while subsequent paragraphs present increasingly general details.

At the far end of the reading difficulty scale are scholarly books and journal articles. Because these texts are written for a specialized, highly educated audience, the authors presume their readers are already familiar with the topic. The language and writing style is sophisticated and sometimes dense.

When you read scholarly books and journal articles, try to apply the same strategies discussed earlier. The introduction usually presents the writer’s thesis , the idea or hypothesis the writer is trying to prove. Headings and subheadings can help you understand how the writer has organized support for his or her thesis. Additionally, academic journal articles often include a summary at the beginning, called an abstract, and electronic databases include summaries of articles, too.

For more information about reading different types of texts, see Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” .

Monitoring Your Comprehension

Finding the main idea and paying attention to text features as you read helps you figure out what you should know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

Textbooks often include comprehension questions in the margins or at the end of a section or chapter. As you read, stop occasionally to answer these questions on paper or in your head. Use them to identify sections you may need to reread, read more carefully, or ask your instructor about later.

Even when a text does not have built-in comprehension features, you can actively monitor your own comprehension. Try these strategies, adapting them as needed to suit different kinds of texts:

- Summarize. At the end of each section, pause to summarize the main points in a few sentences. If you have trouble doing so, revisit that section.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. Write down your questions and use them to test yourself on the reading. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Is the answer buried in that section of reading but just not coming across to you? Or do you expect to find the answer in another part of the reading?

- Do not read in a vacuum. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading with your classmates. Many instructors set up online discussion forums or blogs specifically for that purpose. Participating in these discussions can help you determine whether your understanding of the main points is the same as your peers’.

These discussions can also serve as a reality check. If everyone in the class struggled with the reading, it may be exceptionally challenging. If it was a breeze for everyone but you, you may need to see your instructor for help.

As a working mother, Crystal found that the best time to get her reading done was in the evening, after she had put her four-year-old to bed. However, she occasionally had trouble concentrating at the end of a long day. She found that by actively working to summarize the reading and asking and answering questions, she focused better and retained more of what she read. She also found that evenings were a good time to check the class discussion forums that a few of her instructors had created.

Choose any text that that you have been assigned to read for one of your college courses. In your notes, complete the following tasks:

- Summarize the main points of the text in two to three sentences.

- Write down two to three questions about the text that you can bring up during class discussion.

Students are often reluctant to seek help. They feel like doing so marks them as slow, weak, or demanding. The truth is, every learner occasionally struggles. If you are sincerely trying to keep up with the course reading but feel like you are in over your head, seek out help. Speak up in class, schedule a meeting with your instructor, or visit your university learning center for assistance.

Deal with the problem as early in the semester as you can. Instructors respect students who are proactive about their own learning. Most instructors will work hard to help students who make the effort to help themselves.

Taking It to the Next Level: Active Reading

Now that you have acquainted (or reacquainted) yourself with useful planning and comprehension strategies, college reading assignments may feel more manageable. You know what you need to do to get your reading done and make sure you grasp the main points. However, the most successful students in college are not only competent readers but active, engaged readers.

Using the SQ3R Strategy

One strategy you can use to become a more active, engaged reader is the SQ3R strategy , a step-by-step process to follow before, during, and after reading. You may already use some variation of it. In essence, the process works like this:

- Survey the text in advance.

- Form questions before you start reading.

- Read the text.

- Recite and/or record important points during and after reading.

- Review and reflect on the text after you read.

Before you read, you survey, or preview, the text. As noted earlier, reading introductory paragraphs and headings can help you begin to figure out the author’s main point and identify what important topics will be covered. However, surveying does not stop there. Look over sidebars, photographs, and any other text or graphic features that catch your eye. Skim a few paragraphs. Preview any boldfaced or italicized vocabulary terms. This will help you form a first impression of the material.

Next, start brainstorming questions about the text. What do you expect to learn from the reading? You may find that some questions come to mind immediately based on your initial survey or based on previous readings and class discussions. If not, try using headings and subheadings in the text to formulate questions. For instance, if one heading in your textbook reads “Medicare and Medicaid,” you might ask yourself these questions:

- When was Medicare and Medicaid legislation enacted? Why?

- What are the major differences between these two programs?

Although some of your questions may be simple factual questions, try to come up with a few that are more open-ended. Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

The next step is simple: read. As you read, notice whether your first impressions of the text were correct. Are the author’s main points and overall approach about the same as what you predicted—or does the text contain a few surprises? Also, look for answers to your earlier questions and begin forming new questions. Continue to revise your impressions and questions as you read.

While you are reading, pause occasionally to recite or record important points. It is best to do this at the end of each section or when there is an obvious shift in the writer’s train of thought. Put the book aside for a moment and recite aloud the main points of the section or any important answers you found there. You might also record ideas by jotting down a few brief notes in addition to, or instead of, reciting aloud. Either way, the physical act of articulating information makes you more likely to remember it.

After you have completed the reading, take some time to review the material more thoroughly. If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you used during reading, such as in an outline or a list.

As you review the material, reflect on what you learned. Did anything surprise you, upset you, or make you think? Did you find yourself strongly agreeing or disagreeing with any points in the text? What topics would you like to explore further? Jot down your reflections in your notes. (Instructors sometimes require students to write brief response papers or maintain a reading journal. Use these assignments to help you reflect on what you read.)

Choose another text that that you have been assigned to read for a class. Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one session, especially if the text is long.)

Be sure to complete all the steps involved. Then, reflect on how helpful you found this process. On a scale of one to ten, how useful did you find it? How does it compare with other study techniques you have used?

Using Other Active Reading Strategies

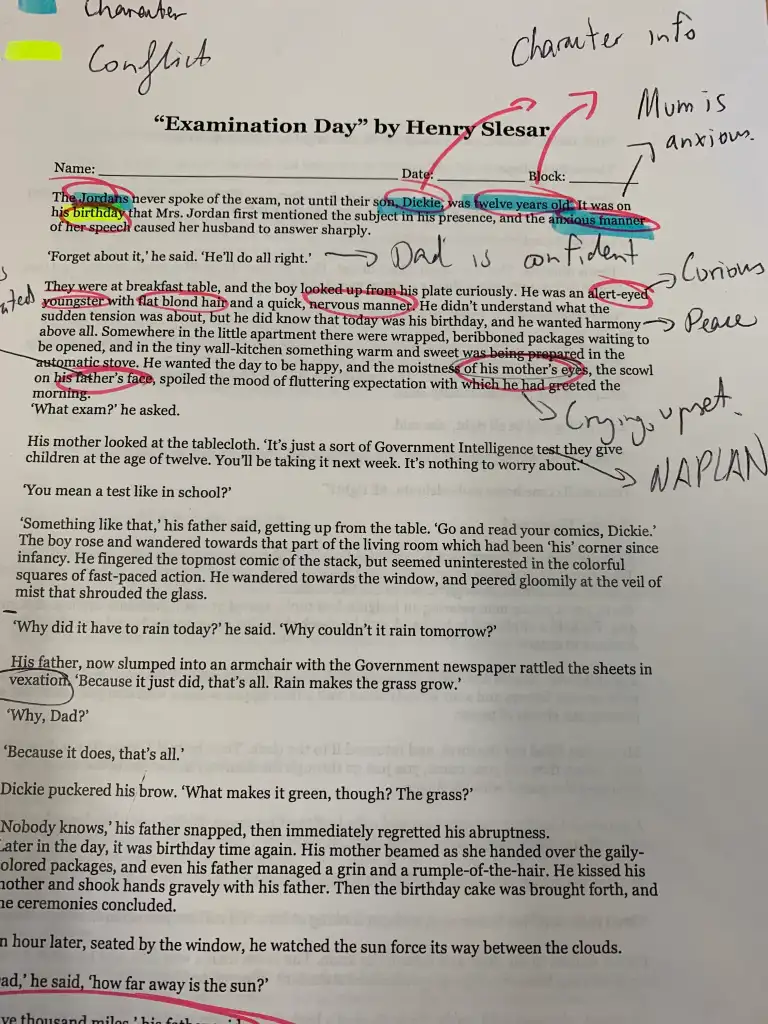

The SQ3R process encompasses a number of valuable active reading strategies: previewing a text, making predictions, asking and answering questions, and summarizing. You can use the following additional strategies to further deepen your understanding of what you read.

- Connect what you read to what you already know. Look for ways the reading supports, extends, or challenges concepts you have learned elsewhere.

- Relate the reading to your own life. What statements, people, or situations relate to your personal experiences?

- Visualize. For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are reading a narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository text that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Pay attention to graphics as well as text. Photographs, diagrams, flow charts, tables, and other graphics can help make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Understand the text in context. Understanding context means thinking about who wrote the text, when and where it was written, the author’s purpose for writing it, and what assumptions or agendas influenced the author’s ideas. For instance, two writers might both address the subject of health care reform, but if one article is an opinion piece and one is a news story, the context is different.

- Plan to talk or write about what you read. Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

As Crystal began her first semester of elementary education courses, she occasionally felt lost in a sea of new terms and theories about teaching and child development. She found that it helped to relate the reading to her personal observations of her son and other kids she knew.

Writing at Work

Many college courses require students to participate in interactive online components, such as a discussion forum, a page on a social networking site, or a class blog. These tools are a great way to reinforce learning. Do not be afraid to be the student who starts the discussion.

Remember that when you interact with other students and teachers online, you need to project a mature, professional image. You may be able to use an informal, conversational tone, but complaining about the work load, using off-color language, or “flaming” other participants is inappropriate.

Active reading can benefit you in ways that go beyond just earning good grades. By practicing these strategies, you will find yourself more interested in your courses and better able to relate your academic work to the rest of your life. Being an interested, engaged student also helps you form lasting connections with your instructors and with other students that can be personally and professionally valuable. In short, it helps you get the most out of your education.

Common Writing Assignments

College writing assignments serve a different purpose than the typical writing assignments you completed in high school. In high school, teachers generally focus on teaching you to write in a variety of modes and formats, including personal writing, expository writing, research papers, creative writing, and writing short answers and essays for exams. Over time, these assignments help you build a foundation of writing skills.

In college, many instructors will expect you to already have that foundation.

Your college composition courses will focus on writing for its own sake, helping you make the transition to college-level writing assignments. However, in most other college courses, writing assignments serve a different purpose. In those courses, you may use writing as one tool among many for learning how to think about a particular academic discipline.

Additionally, certain assignments teach you how to meet the expectations for professional writing in a given field. Depending on the class, you might be asked to write a lab report, a case study, a literary analysis, a business plan, or an account of a personal interview. You will need to learn and follow the standard conventions for those types of written products.

Finally, personal and creative writing assignments are less common in college than in high school. College courses emphasize expository writing, writing that explains or informs. Often expository writing assignments will incorporate outside research, too. Some classes will also require persuasive writing assignments in which you state and support your position on an issue. College instructors will hold you to a higher standard when it comes to supporting your ideas with reasons and evidence.

Table 1.2 “Common Types of College Writing Assignments” lists some of the most common types of college writing assignments. It includes minor, less formal assignments as well as major ones. Which specific assignments you encounter will depend on the courses you take and the learning objectives developed by your instructors.

Table 1.2 Common Types of College Writing Assignments

| Assignment Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Expresses and explains your response to a reading assignment, a provocative quote, or a specific issue; may be very brief (sometimes a page or less) or more in-depth | For an environmental science course, students watch and write about President Obama’s June 15, 2010, speech about the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. | |

| Restates the main points of a longer passage objectively and in your own words | For a psychology course, students write a one-page summary of an article about a man suffering from short-term memory loss. | |

| States and defends your position on an issue (often a controversial issue) | For a medical ethics course, students state and support their position on using stem cell research in medicine. | |

| Presents a problem, explains its causes, and proposes and explains a solution | For a business administration course, a student presents a plan for implementing an office recycling program without increasing operating costs. | |

| States a thesis about a particular literary work (or works) and develops the thesis with evidence from the work and, sometimes, from additional sources | For a literature course, a student compares two novels by the twentieth-century African American writer Richard Wright. | |

| Sums up available research findings on a particular topic | For a course in media studies, a student reviews the past twenty years of research on whether violence in television and movies is correlated with violent behavior. | |

| Investigates a particular person, group, or event in depth for the purpose of drawing a larger conclusion from the analysis | For an education course, a student writes a case study of a developmentally disabled child whose academic performance improved because of a behavioral-modification program. | |

| Presents a laboratory experiment, including the hypothesis, methods of data collection, results, and conclusions | For a psychology course, a group of students presents the results of an experiment in which they explored whether sleep deprivation produced memory deficits in lab rats. | |

| Records a student’s ideas and findings during the course of a long-term research project | For an education course, a student maintains a journal throughout a semester-long research project at a local elementary school. | |

| Presents a thesis and supports it with original research and/or other researchers’ findings on the topic; can take several different formats depending on the subject area | For examples of typical research projects, see . |

Part of managing your education is communicating well with others at your university. For instance, you might need to e-mail your instructor to request an office appointment or explain why you will need to miss a class. You might need to contact administrators with questions about your tuition or financial aid. Later, you might ask instructors to write recommendations on your behalf.

Treat these documents as professional communications. Address the recipient politely; state your question, problem, or request clearly; and use a formal, respectful tone. Doing so helps you make a positive impression and get a quicker response.

Key Takeaways

- College-level reading and writing assignments differ from high school assignments not only in quantity but also in quality.

- Managing college reading assignments successfully requires you to plan and manage your time, set a purpose for reading, practice effective comprehension strategies, and use active reading strategies to deepen your understanding of the text.

- College writing assignments place greater emphasis on learning to think critically about a particular discipline and less emphasis on personal and creative writing.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

3.3 Effective Reading Strategies

| Estimated completion time: 25 minutes. |

Questions to Consider:

- What methods can you incorporate into your routine to allow adequate time for reading?

- What are the benefits and approaches to active and critical reading?

- Do your courses or major have specific reading requirements?

Allowing Adequate Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class very early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your instructor asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment.

Depending on the makeup of your schedule, you may end up reading both primary sources—such as legal documents, historic letters, or diaries—as well as textbooks, articles, and secondary sources, such as summaries or argumentative essays that use primary sources to stake a claim. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay up to date in local or global affairs. A realistic approach to scheduling your time to allow you to read and review all the reading you have for the semester will help you accomplish what can sometimes seem like an overwhelming task.

When you allow adequate time in your hectic schedule for reading, you are investing in your own success. Reading isn’t a magic pill, but it may seem like it when you consider all the benefits people reap from this ordinary practice. Famous successful people throughout history have been voracious readers. In fact, former U.S. president Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” Writer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, inventor, and also former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson claimed “I cannot live without books” at a time when keeping and reading books was an expensive pastime. Knowing what it meant to be kept from the joys of reading, 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” And finally, George R. R. Martin, the prolific author of the wildly successful Game of Thrones empire, declared, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.”

You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include determining your usual reading pace and speed, scheduling active reading sessions, and practicing recursive reading strategies.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing

To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine your average reading pace (5 times 12 equals the 60 minutes of an hour). Of course, your reading pace will be different and take longer if you are taking notes while you read, but this calculation of reading pace gives you a good way to estimate your reading speed that you can adapt to other forms of reading.

| Reader | Pages Read in 5 Minutes | Pages per Hour | Approximate Hours to Read 500 Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marta | 4 | 48 | 10 hours, 30 minutes |

| Jordi | 3 | 36 | 13 hours |

| Estevan | 5 | 60 | 8 hours, 20 minutes |

In the table above, you can see three students with different reading speeds. So, for instance, if Marta was able to read 4 pages of a dense novel for her English class in 5 minutes, she should be able to read about 48 pages in one hour. Knowing this, Marta can accurately determine how much time she needs to devote to finishing the novel within a set amount of time, instead of just guessing. If the novel Marta is reading is 497 pages, then Marta would take the total page count (497) and divide that by her hourly reading rate (48 pages/hour) to determine that she needs about 10 to 11 hours overall. To finish the novel spread out over two weeks, Marta needs to read a little under an hour a day to accomplish this goal.

Calculating your reading rate in this manner does not take into account days where you’re too distracted and you have to reread passages or days when you just aren’t in the mood to read. And your reading rate will likely vary depending on how dense the content you’re reading is (e.g., a complex textbook vs. a comic book). Your pace may slow down somewhat if you are not very interested in what the text is about. What this method will help you do is be realistic about your reading time as opposed to waging a guess based on nothing and then becoming worried when you have far more reading to finish than the time available.

Chapter 2 , “ Managing Your Time and Priorities ,” offers more detail on how best to determine your speed from one type of reading to the next so you are better able to schedule your reading.

Scheduling Set Times for Active Reading

Active reading takes longer than reading through passages without stopping. You may not need to read your latest sci-fi series actively while you’re lounging on the beach, but many other reading situations demand more attention from you. Active reading is particularly important for college courses. You are a scholar actively engaging with the text by posing questions, seeking answers, and clarifying any confusing elements. Plan to spend at least twice as long to read actively than to read passages without taking notes or otherwise marking select elements of the text.

To determine the time you need for active reading, use the same calculations you use to determine your traditional reading speed and double it. Remember that you need to determine your reading pace for all the classes you have in a particular semester and multiply your speed by the number of classes you have that require different types of reading. The table below shows the differences in time needed between reading quickly without taking notes and reading actively.

| Reader | Pages Read in 5 Minutes | Pages per Hour | Approximate Hours to Read 500 Pages | Approximate Hours to Actively Read 500 Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marta | 4 | 48 | 10 hours, 30 minutes | 21 hours |

| Jordi | 3 | 36 | 13 hours | 26 hours |

| Estevan | 5 | 60 | 8 hours, 20 minutes | 16 hours, 40 minutes |

Practicing Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for college courses that may become frustrating is that, in a way, it never ends. For all the reading you do, you end up doing even more rereading. It may be the same content, but you may be reading the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This rereading is called recursive reading.

For most of what you read at the college level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose—not just because the topic interests or entertains you. You need your full attention to decipher everything that’s going on in complex reading material—and you even need to be considering what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive.

Specifically, this boils down to seeing reading not as a formula but as a process that is far more circular than linear. You may read a selection from beginning to end, which is an excellent starting point, but for comprehension, you’ll need to go back and reread passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and the bigger learning environment that led you to the selection—that may be a single course or a program in your college, or it may be the larger discipline, such as all biologists or the community of scholars studying beach erosion.

People often say writing is rewriting. For college courses, reading is rereading, but rereading with the intention of improving comprehension and taking notes.

Strong readers engage in numerous steps, sometimes combining more than one step simultaneously, but knowing the steps nonetheless. They include, not always in this order:

- bringing any prior knowledge about the topic to the reading session,

- asking yourself pertinent questions, both orally and in writing, about the content you are reading,

- inferring and/or implying information from what you read,

- learning unfamiliar discipline-specific terms,

- evaluating what you are reading, and eventually,

- applying what you’re reading to other learning and life situations you encounter.

Let’s break these steps into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

Application

Imagine that you were given a chapter to read in your American history class about the Gettysburg Address, now write down what you already know about this historic document. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text?

Asking Questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my professor assign this reading?

You need a place where you can actually write down these questions; a separate page in your notes is a good place to begin. If you are taking notes on your computer, start a new document and write down the questions. Leave some room to answer the questions when you begin and again after you read.

Inferring and Implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer , or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the professor will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test.

Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer may not want to come out explicitly and state a bias, but may imply or hint at his or her preference for one political party or another. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning Vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. Few people beyond undertakers and archeologists likely use the term sarcophagus in everyday communications, but for those disciplines, it is a meaningful distinction. Looking at the example, you can use context clues to figure out the meaning of the term sarcophagus because it is something undertakers and/or archeologists would recognize. At the very least, you can guess that it has something to do with death. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Intelligent people always question and evaluate. This doesn’t mean they don’t trust others; they just need verification of facts to understand a topic well. It doesn’t make sense to learn incomplete or incorrect information about a subject just because you didn’t take the time to evaluate all the sources at your disposal. When early explorers were afraid to sail the world for fear of falling off the edge, they weren’t stupid; they just didn’t have all the necessary data to evaluate the situation.

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings.

- Read through the entire passage fully.

- Question what main point the author is making.

- Decide who the audience is.

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses.

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point.

- Recognize if the author introduced any biases in the text.

When you go through a text looking for each of these elements, you need to go beyond just answering the surface question; for instance, the audience may be a specific field of scientists, but could anyone else understand the text with some explanation? Why would that be important?

Analysis Question

Think of an article you need to read for a class. Take the steps above on how to evaluate a text, and apply the steps to the article. When you accomplish the task in each step, ask yourself and take notes to answer the question: Why is this important? For example, when you read the title, does that give you any additional information that will help you comprehend the text? If the text were written for a different audience, what might the author need to change to accommodate that group? How does an author’s bias distort an argument? This deep evaluation allows you to fully understand the main ideas and place the text in context with other material on the same subject, with current events, and within the discipline.

When you learn something new, it always connects to other knowledge you already have. One challenge we have is applying new information. It may be interesting to know the distance to the moon, but how do we apply it to something we need to do? If your biology instructor asked you to list several challenges of colonizing Mars and you do not know much about that planet’s exploration, you may be able to use your knowledge of how far Earth is from the moon to apply it to the new task. You may have to read several other texts in addition to reading graphs and charts to find this information.

That was the challenge the early space explorers faced along with myriad unknowns before space travel was a more regular occurrence. They had to take what they already knew and could study and read about and apply it to an unknown situation. These explorers wrote down their challenges, failures, and successes, and now scientists read those texts as a part of the ever-growing body of text about space travel. Application is a sophisticated level of thinking that helps turn theory into practice and challenges into successes.

Preparing to Read for Specific Disciplines in College

Different disciplines in college may have specific expectations, but you can depend on all subjects asking you to read to some degree. In this college reading requirement, you can succeed by learning to read actively, researching the topic and author, and recognizing how your own preconceived notions affect your reading. Reading for college isn’t the same as reading for pleasure or even just reading to learn something on your own because you are casually interested.

In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, books, or primary sources (those original documents about which we write and study, such as letters between historic figures or the Declaration of Independence). Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

If you are about to participate in an in-depth six-week consideration of the U.S. Constitution but have never read it or anything written about it, you will have a hard time looking at anything in detail or understanding how and why it is significant. As you can imagine, a great deal has been written about the Constitution by scholars and citizens since the late 1700s when it was first put to paper (that’s how they did it then). While the actual document isn’t that long (about 12–15 pages depending on how it is presented), learning the details on how it came about, who was involved, and why it was and still is a significant document would take a considerable amount of time to read and digest. So, how do you do it all? Especially when you may have an instructor who drops hints that you may also love to read a historic novel covering the same time period . . . in your spare time , not required, of course! It can be daunting, especially if you are taking more than one course that has time-consuming reading lists. With a few strategic techniques, you can manage it all, but know that you must have a plan and schedule your required reading so you are also able to pick up that recommended historic novel—it may give you an entirely new perspective on the issue.

Strategies for Reading in College Disciplines

No universal law exists for how much reading instructors and institutions expect college students to undertake for various disciplines. Suffice it to say, it’s a LOT.

For most students, it is the volume of reading that catches them most off guard when they begin their college careers. A full course load might require 10–15 hours of reading per week, some of that covering content that will be more difficult than the reading for other courses.

You cannot possibly read word-for-word every single document you need to read for all your classes. That doesn’t mean you give up or decide to only read for your favorite classes or concoct a scheme to read 17 percent for each class and see how that works for you. You need to learn to skim, annotate, and take notes. All of these techniques will help you comprehend more of what you read, which is why we read in the first place. We’ll talk more later about annotating and note-taking, but for now consider what you know about skimming as opposed to active reading.

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page (or screen) to see if any of it sticks. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage without the need for a time-consuming reading session that involves your active use of notations and annotations. Often you will need to engage in that painstaking level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. The fact remains that neither do you need to read everything nor could you possibly accomplish that given your limited time. So learn this valuable skill of skimming as an accompaniment to your overall study tool kit, and with practice and experience, you will fully understand how valuable it is.

When you skim, look for guides to your understanding: headings, definitions, pull quotes, tables, and context clues. Textbooks are often helpful for skimming—they may already have made some of these skimming guides in bold or a different color, and chapters often follow a predictable outline. Some even provide an overview and summary for sections or chapters. Use whatever you can get, but don’t stop there. In textbooks that have some reading guides, or especially in texts that do not, look for introductory words such as First or The purpose of this article . . . or summary words such as In conclusion . . . or Finally . These guides will help you read only those sentences or paragraphs that will give you the overall meaning or gist of a passage or book.

Now move to the meat of the passage. You want to take in the reading as a whole. For a book, look at the titles of each chapter if available. Read each chapter’s introductory paragraph and determine why the writer chose this particular order. Depending on what you’re reading, the chapters may be only informational, but often you’re looking for a specific argument. What position is the writer claiming? What support, counterarguments, and conclusions is the writer presenting?

Don’t think of skimming as a way to buzz through a boring reading assignment. It is a skill you should master so you can engage, at various levels, with all the reading you need to accomplish in college. End your skimming session with a few notes—terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. And recognize that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading differs significantly from skimming or reading for pleasure. You can think of active reading as a sort of conversation between you and the text (maybe between you and the author, but you don’t want to get the author’s personality too involved in this metaphor because that may skew your engagement with the text).

When you sit down to determine what your different classes expect you to read and you create a reading schedule to ensure you complete all the reading, think about when you should read the material strategically, not just how to get it all done . You should read textbook chapters and other reading assignments before you go into a lecture about that information. Don’t wait to see how the lecture goes before you read the material, or you may not understand the information in the lecture. Reading before class helps you put ideas together between your reading and the information you hear and discuss in class.

Different disciplines naturally have different types of texts, and you need to take this into account when you schedule your time for reading class material. For example, you may look at a poem for your world literature class and assume that it will not take you long to read because it is relatively short compared to the dense textbook you have for your economics class. But reading and understanding a poem can take a considerable amount of time when you realize you may need to stop numerous times to review the separate word meanings and how the words form images and connections throughout the poem.

The SQ3R Reading Strategy

You may have heard of the SQ3R method for active reading in your early education. This valuable technique is perfect for college reading. The title stands for S urvey, Q uestion, R ead, R ecite, R eview, and you can use the steps on virtually any assigned passage. Designed by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1961 book Effective Study, the active reading strategy gives readers a systematic way to work through any reading material.

Survey is similar to skimming. You look for clues to meaning by reading the titles, headings, introductions, summary, captions for graphics, and keywords. You can survey almost anything connected to the reading selection, including the copyright information, the date of the journal article, or the names and qualifications of the author(s). In this step, you decide what the general meaning is for the reading selection.

Question is your creation of questions to seek the main ideas, support, examples, and conclusions of the reading selection. Ask yourself these questions separately. Try to create valid questions about what you are about to read that have come into your mind as you engaged in the Survey step. Try turning the headings of the sections in the chapter into questions. Next, how does what you’re reading relate to you, your school, your community, and the world?

Read is when you actually read the passage. Try to find the answers to questions you developed in the previous step. Decide how much you are reading in chunks, either by paragraph for more complex readings or by section or even by an entire chapter. When you finish reading the selection, stop to make notes. Answer the questions by writing a note in the margin or other white space of the text.

You may also carefully underline or highlight text in addition to your notes. Use caution here that you don’t try to rush this step by haphazardly circling terms or the other extreme of underlining huge chunks of text. Don’t over-mark. You aren’t likely to remember what these cryptic marks mean later when you come back to use this active reading session to study. The text is the source of information—your marks and notes are just a way to organize and make sense of that information.

Recite means to speak out loud. By reciting, you are engaging other senses to remember the material—you read it (visual) and you said it (auditory). Stop reading momentarily in the step to answer your questions or clarify confusing sentences or paragraphs. You can recite a summary of what the text means to you. If you are not in a place where you can verbalize, such as a library or classroom, you can accomplish this step adequately by saying it in your head; however, to get the biggest bang for your buck, try to find a place where you can speak aloud. You may even want to try explaining the content to a friend.

Review is a recap. Go back over what you read and add more notes, ensuring you have captured the main points of the passage, identified the supporting evidence and examples, and understood the overall meaning. You may need to repeat some or all of the SQR3 steps during your review depending on the length and complexity of the material. Before you end your active reading session, write a short (no more than one page is optimal) summary of the text you read.

Reading Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary sources are original documents we study and from which we glean information; primary sources include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Readers have to keep several factors in mind when reading both primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. It may contain personal beliefs and biases the original writer didn’t intend to be openly published, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases or preferences the secondary source writer inserts in the writing that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner.

For example, if you were to read a secondary source that is examining the U.S. Declaration of Independence (the primary source), you would have a much clearer idea of how the secondary source scholar presented the information from the primary source if you also read the Declaration for yourself instead of trusting the other writer’s interpretation. Most scholars are honest in writing secondary sources, but you as a reader of the source are trusting the writer to present a balanced perspective of the primary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source. The Internet helps immensely with this practice.

Researching Topic and Author

During your preview stage, sometimes called pre-reading, you can easily pick up on information from various sources that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. If your selection is a book, flip it over or turn to the back pages and look for an author’s biography or note from the author. See if the book itself contains any other information about the author or the subject matter.

The main things you need to recall from your reading in college are the topics covered and how the information fits into the discipline. You can find these parts throughout the textbook chapter in the form of headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations pulled out of the narrative. Use these features as you read to help you determine what the most important ideas are.