- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE FINAL EDITION

by Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 3, 2021

Students of design, politics, economics, and many other fields will delight in these provocative discussions.

A fully revised version of the 2008 bestseller about making decisions.

Thaler and Sunstein advocate what they call “libertarian paternalism,” by which consumers and citizens can be “nudged” to make decisions of their own will that guide them and society toward a more perfect union. For instance, they write, “nudges”—usually matters of design in presenting the choices to be made, from whether to tip a cab driver to combatting the deleterious effects of climate change—can be coupled with other mechanisms, including taxes and even outright bans. In the case of Scandinavian countries, for instance, drunken driving is discouraged through high taxes on alcohol, nudges of various kinds to shame drink-impaired drivers from getting behind the wheel, and harsh penalties for anyone caught driving drunk. As for climate change, “we will need jackhammers and bulldozers, with pocketknives helping where they can.” In other words, every tool helps, from nudges that encourage people to lighten their carbon footprints to cap-and-trade agreements. The authors argue effectively against what they call “required choice,” preferring instead for vendors and governments to provide transparent information, such as labeling products that contain shellfish or peanuts so that those allergic to them can avoid buying them. Still, they allow, there are instances in which required choice is the best solution: One should be able to choose whether to buy one kind of canned soup over another but perhaps not to dictate the ingredients of every restaurant meal. In the spirit of Donald Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things , which they cite, Thaler and Sunstein deliver a spirited argument to enable well-informed people to overcome various biases and “probabilistic harms” to do what is best for them and, in the present case, their fellow “American Humans.”

Pub Date: Aug. 3, 2021

ISBN: 978-0-14-313700-9

Page Count: 384

Publisher: Penguin

Review Posted Online: May 17, 2021

Kirkus Reviews Issue: June 1, 2021

CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES | PSYCHOLOGY | BUSINESS | U.S. GOVERNMENT | PUBLIC POLICY | LEADERSHIP, MANAGEMENT & COMMUNICATION | ECONOMICS | GENERAL CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES

Share your opinion of this book

More by Richard H. Thaler

- BOOK REVIEW

by Richard H. Thaler

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2020

BEYOND THE GENDER BINARY

From the pocket change collective series.

by Alok Vaid-Menon ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 2, 2020

A fierce, penetrating, and empowering call for change.

Artist and activist Vaid-Menon demonstrates how the normativity of the gender binary represses creativity and inflicts physical and emotional violence.

The author, whose parents emigrated from India, writes about how enforcement of the gender binary begins before birth and affects people in all stages of life, with people of color being especially vulnerable due to Western conceptions of gender as binary. Gender assignments create a narrative for how a person should behave, what they are allowed to like or wear, and how they express themself. Punishment of nonconformity leads to an inseparable link between gender and shame. Vaid-Menon challenges familiar arguments against gender nonconformity, breaking them down into four categories—dismissal, inconvenience, biology, and the slippery slope (fear of the consequences of acceptance). Headers in bold font create an accessible navigation experience from one analysis to the next. The prose maintains a conversational tone that feels as intimate and vulnerable as talking with a best friend. At the same time, the author's turns of phrase in moments of deep insight ring with precision and poetry. In one reflection, they write, “the most lethal part of the human body is not the fist; it is the eye. What people see and how people see it has everything to do with power.” While this short essay speaks honestly of pain and injustice, it concludes with encouragement and an invitation into a future that celebrates transformation.

Pub Date: June 2, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-593-09465-5

Page Count: 64

Publisher: Penguin Workshop

Review Posted Online: March 14, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: April 1, 2020

TEENS & YOUNG ADULT NONFICTION | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT SOCIAL THEMES | TEENS & YOUNG ADULT BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR

More In The Series

by Shavone Charles ; illustrated by Ashley Lukashevsky

by Gaby Melian

by Leo Baker ; illustrated by Ashley Lukashevsky

Google Rating

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2016

New York Times Bestseller

Pulitzer Prize Finalist

WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR

by Paul Kalanithi ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 19, 2016

A moving meditation on mortality by a gifted writer whose dual perspectives of physician and patient provide a singular...

A neurosurgeon with a passion for literature tragically finds his perfect subject after his diagnosis of terminal lung cancer.

Writing isn’t brain surgery, but it’s rare when someone adept at the latter is also so accomplished at the former. Searching for meaning and purpose in his life, Kalanithi pursued a doctorate in literature and had felt certain that he wouldn’t enter the field of medicine, in which his father and other members of his family excelled. “But I couldn’t let go of the question,” he writes, after realizing that his goals “didn’t quite fit in an English department.” “Where did biology, morality, literature and philosophy intersect?” So he decided to set aside his doctoral dissertation and belatedly prepare for medical school, which “would allow me a chance to find answers that are not in books, to find a different sort of sublime, to forge relationships with the suffering, and to keep following the question of what makes human life meaningful, even in the face of death and decay.” The author’s empathy undoubtedly made him an exceptional doctor, and the precision of his prose—as well as the moral purpose underscoring it—suggests that he could have written a good book on any subject he chose. Part of what makes this book so essential is the fact that it was written under a death sentence following the diagnosis that upended his life, just as he was preparing to end his residency and attract offers at the top of his profession. Kalanithi learned he might have 10 years to live or perhaps five. Should he return to neurosurgery (he could and did), or should he write (he also did)? Should he and his wife have a baby? They did, eight months before he died, which was less than two years after the original diagnosis. “The fact of death is unsettling,” he understates. “Yet there is no other way to live.”

Pub Date: Jan. 19, 2016

ISBN: 978-0-8129-8840-6

Page Count: 248

Publisher: Random House

Review Posted Online: Sept. 29, 2015

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Oct. 15, 2015

GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | CURRENT EVENTS & SOCIAL ISSUES

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Nudge: Summary, Review & Criticism

Nudge explains how policymakers can leverage psychology and social psychology to “ nudge ” people towards choices that are better for them and for society at large.

Nudge Quotes

Real-life applications.

About the Authors : “ Nudge ” is co-authored by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler. Thaler is a Nobel Prize winner and I loved his book “ Misbehaving “, which explains how psychology improved our understanding of economics to give birth to “Behavioral Psychology”.

#1. What’s A Nudge

The authors define a “ nudge ” as:

Any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any option or significantly changing their economic incentives

A nudge but also be simple to avoid if an individual wants to choose differently.

Choice Architecture

Choice architecture refers to the way and order in which you present the options and opportunities.

The way you present your options will naturally nudge towards one or another direction.

#2. The Rationale for “Nudging”: Libertarian Paternalism

Sunstein and Thaler explain that we don’t make rational choices that are best for ourselves and/or for our society. As a matter of fact, we often make choices that are bad either for us, for society, or both .

They make the case that we could use our knowledge of psychology to “ nudge ” people toward the best choice but ultimately let people decide if they want to do something different.

They call this stance “libertarian paternalism”.

Libertarian paternalism is about nudging towards the best choice but allowing the individual to also reject that choice .

Libertarian paternalism promotes the best choice to increase its acceptance and to help the majority of people make the best choice. The majority of people often operate in environments in which they might not know what’s the best choice, and they are likely to want and accept the nudge (ie.: choosing the best mortgage, the best health care coverage, etc.).

Libertarian paternalism is not about overriding what people want and, if people want to willingly risk high or willingly hurt themselves, they can also be given that choice.

#3. Why We Make the Wrong Choices

In the first quarter of “ Nudge, ” the authors review a few of the reasons why we make wrong choices.

- We pick the default setting (status quo bias)

We have a strong tendency to go along or stick with the default setting. For example, few people choose “custom installation” on their software.

And few people opt out of organ donation if that’s the default setting in their country. Yet, very few people opt-in to donate their organs because that’s not the default setting and because it goes against the path of least resistance (next item on the list).

- We pick the path of least resistance

We have a strong tendency to follow the path of least resistance. The path of least resistance it’s often the default setting, but the two are not exactly the same.

For example, depending on how items are stocked in a supermarket or a cafeteria, people end up consuming different quantities of food because some of them will be more convenient to reach.

- We use simplistic heuristics

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that, often, lead us to the wrong conclusions.

Among the heuristics are anchoring, availability, representativeness, overconfidence, loss aversion, etc. (read more in “ Thinking Fast and Slow “).

The most important fact to remember about heuristics is that they prevent us from optimal decision-making.

- We choose mindlessly

For some activities, we end up choosing at random even though the consequences might be important (eating, for example, as an experiment proved we don’t eat till we’re full but based on the dish size).

- We use poor mental accounting

Mental accounting is a topic very dear to Richard Thaler as it’s strictly related to behavioral economics. In brief, it says that we are not rational with the way we spend, save, or invest our money.

- We don’t understand randomness

We see more relations than actually exist (hot-hand fallacy) and end up jumping to conclusions that are often wrong.

We also have a poor understanding of randomness and we expect randomness to look random. But randomness is “XXX” much as it is “YXY” (example of London bombing map).

Also read “ Fooled by Randomness “.

#4. Temptation & Arousal

Finally, temptation deserves its own chapter. Temptation, coupled with mindlessness and arousal, is what leads most people down a path they don’t really want.

We don’t want to get fat and unhealthy, yet we keep staying on the couch when we know we should move.

And we smoke that pack of cigarettes even when we know we shouldn’t.

In these situations, nudging can be very helpful to get us going in the right direction and to decrease the incidence of smoking and obesity in the population.

Arousal refers to the bad decisions we make in a state of arousal, which we always underestimate when we’re not aroused (example of Ulysses tying himself to a mast).

#5. How to Nudge

The authors provide a lot of ideas from social-psychology research on how we can effectively nudge people.

For example:

- To decrease pollution, publish a list of the most polluting companies

- To increase saving rates, make contributions towards retirement plans the default option

If you are interested in more practical applications of persuasion, also check out Pre-Suasion , Influence , and “ best books on persuasion “.

Companies Already Use Nudging for Manipulation

Companies have an incentive to misuse nudging to make you spend more. For example, they can pre-select options that are better for them but not necessarily for you.

Why don’t these imperfections get corrected by the market? The author says that markets are not perfect and there is no invisible hand to always fix mispricings (or punish abusive practices).

When the costs are hidden or difficult to find out, companies keep selling overpriced products and services. Extended warranties are one such example

Also read “ how corporations manipulate you “.

More Applications of Libertarian Paternalism

The authors also go a bit further astray from nudging and expand on the concept of libertarian paternalism.

For example, they talk about:

- Reducing healthcare costs by foregoing the “right to sue”

- Automatically investing a higher portion of pay rises (which has a different mental accounting)

- Lock away money saved from cigarettes and only unlock it if smoke-free

The Morality of Nudging: It’s OK As Long As It’s Good For The Nudged

Libertarian paternalism is a policy choice and, as such, its acceptance varies heavily depending on political affiliations.

Says the authors:

Our basic conclusions is that the evalution of nudges depends on their effects. Whether they hurt people or help them.

The authors say that it’s not possible to avoid “choice architecture” and, hence, it’s not possible to avoid nudging people.

Thus, “positive nudging” is the only possible way.

On climate change:

If the problem of climate change is to be seriously addressed, the ultimate strategy is based on incentives and not on demand and control

I love books like “ Nudge ” which can sprinkle some great humor together with the bountiful wisdom they share. For example:

The group average does exert a significant influence, but there are exceptions. A woman will eat less on dates and a man will eat more in the belief that women are impressed by maly eating. Not for men: they’re not

On extended warranties and their general overprice:

Please note that extended are plentiful in the extended world and many people buy them. Hint: don’t

On the of “homo economicus”, which the author calls “econ”:

If you are an econ, you can skip this section of the book. Unless you want to understand the behavior of your spouse, kids, and other humans.

On getting informed ahead of troubles:

If you are married or plan to get married, do you know your state’s laws on alimony and child support? Oh, never mind, there is no chance that you will divorce

- Nudging to spend without guilt

Nudging in the US means enticing people to save more.

But for some people -like yours truly- the problem is not in saving, but in spending freely and without guilt. You can nudge yourself to spend more freely and without worrying, for example, by designating an account as a “fun account” outside of your normal accounting.

- Boomerang effect : don’t let people know their actions are better than the social norm

When you let people that their actions are better than the social norm, they feel like they can let themselves go and have “goodwill to spend”.

But the exception is when you make them feel good for their choices, in which case they don’t adjust.

- Nudging in interaction designs

Product designers should understand psychology to design good and functional products (and many don’t).

On the remote, for example, the “on” button should be the biggest, together with volume. But often, they’re not.

- Stocks are almost certain to go up (really???)

I can’t believe an author I respect as much as Thaler did come up with this BS. How on earth can he say that “on a 20-year period stocks are almost certainly to go up”?? If a war started, are stocks likely to go up?

- Some debunked psychology

Some of the examples in “ Nudge ” have been relegated to debunked psychology in the recent replication crisis .

Nudge is 30% psychology and 70% government policy.

I enjoyed the psychology part albeit there is some valid criticism to what’s included as a “nudge” and the validity of some studies. And I agree with several of the pro-social government policies it encourages.

- Best books on psychology

or get the book on Amazon

About The Author

Lucio Buffalmano

Related posts.

I’m OK – You’re OK: Summary & Review

Straight Talk, No Chaser: Summary & Review

Snakes in Suits: Summary & Review

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Book Review-Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness

Home Adoption and Change Book Review ... Book Review-Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness

- April 10, 2017

- No Comments

- Robert Bogue

- Adoption and Change , Book Review , Professional

It’s an artful thing to create the right choices so that people are nudged gently into the behaviors that are best for them. That’s what Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness is all about – helping people make the best choices for themselves. With the idea of libertarian paternalism, choice architects help to shape the way that people choose.

Choice Architects

Inherent in the idea that you can nudge someone is that doing so is subtle and something they barely notice. There is no such thing as a completely neutral design. Simple psychological factors, like the desire to pick the first option, means that choice architects carefully manage whose name is first on a ballot. Choice architects are the ones that are structuring the system such that the choice that is the best for people is the one they get most of the time.

Most of the time when we’re consumers, we have no idea what work has gone into the choice architecture. We don’t know that we’re subtly being engaged in ways that help us – or help the organization that we’re shopping with. However, these subtle influences are there, as we find impulse items on the end of the shelves in grocery stores and drive past stores that are having going out of business sales – continuously.

As architects of choices we rarely consider all the factors that might go into someone selecting a particular choice. Instead, we create a list of choices quickly and move on. Rarely do we think about the order that the choices occur in or what the default answer should be.

Nudge insists that there is no neutral choice design. So whatever we do, whether by intent or by design, will shift the results – at least slightly.

Libertarian Paternalism

Paternalism is thinking about the consumer as a child who cannot make good decisions. Authoritarian or dictatorial paternalism restricts the choices that consumers have, and only gives them the solution that they must “choose” because someone – a choice architect – said this is the only solution for them. Most of us would resist this attempt to enforce a choice on us. It’s what we expect out of communist dictators, and, certainly in the United States, we’re not going to stand for it.

Libertarian paternalism has the same basis but instead of preventing what the choice architect sees as sub-optimal solutions, the choices are allowed, but they’re deemphasized. The degree to which you must go out of your way to pick a different choice is a measure of how truly libertarian it is. If it’s easy to choose, it’s libertarian. If it’s hard to choose, it’s more authoritarian – disguised as a real choice.

The authors believe that libertarian paternalism is OK, or even a moral obligation where authoritarian paternalism is wrong, but admit that the line between these two extremes isn’t always the easiest to distinguish.

The goal is to balance the number of people getting the perceived optimal solution while maintaining their ability to make choices for themselves.

The Paradox of Choice

The first step is to ensure that the person has as many options available as makes sense. The challenge with this is knowing how many options make sense. In an ideal world, every option would be available to the chooser, but in a practical world, choices promote inaction, and inaction is frequently (if not always) not the best option.

The Paradox of Choice skillfully points out that we like our choices less the more options we have – and we make fewer decisions. In short, more options are the enemy to actions. If we want someone to make a choice, we need to manage the number of options.

Forced Choice

Brené Brown is careful when confronted with forced choices – “either-or dilemmas,” as she calls them. She wonders in Rising Strong who has something to gain by forcing the choice. In the case of our nudges, the hope is that the person making the choice is benefited. With an ethical choice architect, the forced choice causes the person to steer their own course. With luck, the choice architect created the situation to keep most of the people off the rocks most of the time.

The forced choice is a tool of the choice architect. They get to make someone choose between A or B, and in the process cause the person to indicate what they think is better. The problem with the forced choice, in addition to whether it really serves the person making the choice, is that too few people take action, even when faced with a straightforward choice, and what is to be done with the folks that fail to make a choice.

The Power of Default

The next tool in the choice architect’s toolbox is the power of the default option. If you do nothing, you’ll get option C. This option is often very powerful in terms of the number of people that fall into it. The option is typically one which isn’t particularly risky, because no one wants to inflict undue risk on someone just because they didn’t decide; so the choice architect creates a safer, but less rewarding, option to be the default.

We learned that the default answer is the one which is taken when neither the rider nor the elephant are paying attention to what’s happening. (See Rider-Elephant-Path in The Happiness Hypothesis for more on how powerful the defaults are.) The default is all too often the most popular answer, because people making the decisions are neither experts nor sufficiently engaged to research the correct result.

Without insisting that the default is a specific action, most consumers fall victim to the “status quo bias.” That is, they expect that things are going relatively OK now, so why would they change? In fact, while we sometimes describe people as change adverse, it’s not that they’re change adverse at all, they just see no point in it.

John Kotter’s work in The Heart of Change and Leading Change includes a model, in which first step is to break this inertia by creating a sense of urgency. This is sometimes called a “burning platform” from which people must jump. While this is an aggressive strategy, it’s often needed to fight the strong pull of the status quo bias.

Controlled by Experts

Too often, consumers find themselves in a foreign land. The foreign land isn’t on any map that you find, but is instead demarcated by the front door of the store they walk into. Whether it’s buying a new TV or shopping for wine for a special evening, the consumer is rarely as educated as the store workers. In this scenario, it’s relatively easy for the salesperson to overwhelm you with technical jargon and features and to nudge you into purchasing what they want you to buy.

In retail, particularly electronics, it’s common for manufacturers to run contests for store employees based on their ability to sell that manufacturer’s products – sometimes even a single product. In these cases, the manufacturers are intentionally tipping the scales in their direction through nudging the sales folks.

Nudging and Shoving

The distance between a nudge and a shove are often too close to call. Nudges aren’t forced: they are, after all, libertarian paternalism. But even in the spirit of not removing options, sometimes the influence of the “expert” salesperson can drive people to a product in a way that feels more like a shove than a nudge.

The focus of the book is on nudges, though it’s clear that, by knowing what is a nudge and not a shove, there’s an inherent risk that some people will use shoves instead of nudges – because in the short term, they’re often more effective.

Mistakes in Choosing

Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow and Hubbard in How to Measure Anything speak volumes about how our ability to make guesses, the right choices, and decisions can be systemically flawed. The rules of thumb that we use to make our decisions are sometimes grossly distorted in their applicability or effectiveness. I have a deck that isn’t square on the house, because the person I hired used the rule of thumb – based on the Pythagorean theorem – of a side length of 3 feet and a side length of 4 feet should have a diagonal of 5 feet. That’s easy enough when the deck is small, but when it’s a 20′ by 40′ deck, the amount of measurement error is substantial.

It’s because people make so many mistakes in choosing that it’s important that choice architects exist to disrupt the incorrect application of rules of thumb or other knowledge in domains where it’s not helpful.

Unintended Consequences

It used to be that Christmas clubs were great ways for banks to make money. People deposited money on a regular basis in an account that accrued little or no interest. They could withdraw these funds to purchase gifts for Christmas. It was an ingenious idea for the banks and, at a level, helped consumers. No one wanted to be caught short at Christmas and be unable to buy toys for their children. So the banks really won, and the consumers who weren’t capable of saving throughout the year with normal options were given a solution.

However, another choice opened. That is, the ability to charge things on credit. So now, even if you didn’t have the money to pay for the toys that you wanted to get your children, you could borrow that money on a credit card and pay a substantially higher interest rate on the money that you borrowed – making the banks more money.

This is a case where the choices got away from the choice architects but in a way that further favored the banks. No one would have necessarily predicted that credit cards would virtually eliminate Christmas clubs, but that’s what they did. (See Diffusion of Innovations for more on unintended consequences – even on well-intended interventions.)

Social Nudges

While I’ve shared about structural nudges – those relying on the architecture of the situation – they are not necessarily the most powerful. As is revealed in Influencer , there are many ways to influence a person, some of which are social. Social nudges have accomplices who sway the decisions of others. Whether the accomplices are knowing accomplices being paid, or are instead just caught up in the system themselves and decide to amplify the message to capture others through social media, they are accomplices nonetheless.

The researcher Solomon Asch demonstrated that if you asked someone a simple question, you could get 100% right answers – unless the subject heard someone else give the wrong answer. In those cases, even though the questions were easy, the subjects gave incorrect answers as much as 1/3 rd of the time.

So powerful are social nudges that they can sometimes create a panic. In Seattle in 1954, there was an epidemic of windshield pitting – that never actually was. Someone noticed pitting on their windshield and shared this with their friends, who also noticed the pitting. They got together to wonder what was causing this damage to their cars and proceeded to drag more people and media in. That is, until it was finally concluded that pitting was a normal effect of driving a car. The pits had been with the cars all along, but someone noticed them, and concern for folks’ precious cars continued to feed more energy into the epidemic.

This isn’t an isolated incident. It happens all the time where something has been going on “forever”, gets discovered, and becomes some conspiracy plot that must be addressed.

Epidemics are facilitated through a concept called “priming”. That is, we’re more likely to follow a train of thought once it has been laid down. This is at the heart of social hacking. Social hacking is the art of gaining access to systems, equipment, or information by use of social, rather than technical, means. In simple terms, just getting someone to say yes a few times before they answer a question they should tell you no to increases the likelihood that they’ll say yes. (See my book review of Social Hacking for more.)

By creating the expectation that there is something going on or a preferred choice, we sensitize our reticular activating system (RAS) and become more aware. The RAS is important for our wake-sleep cycle, but also pays a critical role in what we look for – and what we look for, we’ll find. (See Change or Die for more on the RAS.)

Checklist for the Choice Architect

As choice architects, we should consider how to create effective nudges, and here’s a book-provided mnemonic for that:

- i N centives

- U nderstand mappings

- G ive feedback

- E xpect error

- S tructure complex choices

You may not get your nudges exactly right but maybe this review is just the nudge you need to read Nudges .

No comment yet, add your voice below!

Add a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Share this:

Recent Posts

September Suicide Prevention

Book Review-The Oz Principle: Getting Results Through Individual and Organizational Accountability

Book Review-Attachment Theory in Practice: Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) with Individuals, Couples, and Families

Book Review-Lonely at the Top: The High Cost of Men’s Success

Book Review-Translate this Darkness: The Life of Christiana Morgan

Public Speaking

Book Review: Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein

Nudge is a book for people who want to help –but not force– others to make better decisions.

I first learned of this book when Daniel Kahneman raved about it in Thinking Fast and Slow . I was looking forward to Nudge and was not disappointed. I recommend it to anyone who might be presenting choices to others, and therefore affecting those choices.

Nudge is about choice architecture : the ways that various factors in how a choice is presented may affect the decisions made by the chooser.

The heart of the book can be summarized through a clever (if imperfect) mnemonic device: NUDGES.

- i N centives (pricing and more: bonuses that can be offered, and even penalties)

- U nderstandable options (or as the authors say “Understand mappings”)

- D efaults (they are often taken, so make the default the best choice)

- G ive feedback (it helps improve the quality of decisions)

- E xpect error (and help people recover from it)

- S tructure complex choices (a small number of choices at a time)

By using NUDGES, choice architects can be more effective at helping people to make better choices. For many excellent examples, from placement of food items in a cafeteria to software that makes you delay sending emails to that seem to be uncivil, read Nudge .

- Jun 1, 2019

Nudge - Book Review

Updated: Aug 12

" Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness ," 2008, 2017, was written by Richard H. Thaler, a Nobel Prize laureate in economics, and Cass R. Sunstein, also distinguished as a Holberg Prize winner.

Central to the book's premise is the introduction of the "nudge" concept – a subtle yet influential force capable of inciting individuals to make favorable choices and take proactive steps. Rooted in a liberal perspective, the authors adeptly navigate the delicate balance between safeguarding freedom of choice and offering gentle guidance. The ensuing summary delineates their methodology, lightly referencing illustrative examples, as the book primarily delves into real-world instances and scenarios showcasing positive shifts underpinned by their economic principles, achievable through the skillful application of nudges. These transformative instances span diverse realms: financial affairs encompassing savings, investments, loans, and the privatization of social security; considerations of well-being spanning insurance, organ donations, and environmental preservation; and matters of civil liberties, spanning the selection of educational institutions, insurance services, and the demarcation of church and state in marital affairs.

Perhaps one of the most globally renowned instances of nudge application is the placement of fly stickers inside urinals at the Amsterdam airport. This measure notably curbed incidents of misalignment.

The book covers the following topics:

NUDGE - Fundamental Concepts and Principles

NUDGE Tools

Peer pressure, aiding in decision-making, simplifying complex processes.

Incentivizing Behaviors

Integrating Knowledge into the NUDGE Framework

Addressing objections to nudge.

This summary is a valuable resource for professionals in knowledge management, product and service planning, and individuals involved in change management. For those desiring deeper insights, it is strongly recommended to delve into the book.

NUDGE - Fundamental Concepts and Principles

Introducing the NUDGE Concept and Its Underlying Principles

To foster a comprehensive comprehension of the NUDGE concept and its bedrock, let us embark by elucidating pertinent terms:

NUDGE – An inconspicuous prod possessing the potential for substantial change or influence. Consider, for instance, the dwindling markings on a fuel gauge, signifying a decline in fuel level; toggling a switch to illuminate a light hastens many of us to refuel, even though this information isn't novel. For clarity, the authors remind us: do not misconstrue this term with the Yiddish "NOODGE," which translates to "snooze" (an entertaining testament to its prevalence…).

CHOICE ARCHITECT – An individual vested with the responsibility of arranging information to facilitate decision-making. This role proves pivotal in deftly navigating the NUDGE concept, assisting us in traversing a world with knowledge and potential.

LIBERTARIAN PATERNALISM – A seemingly paradoxical term that melds liberalism with a modicum of paternalistic influence. It enables individuals' gentle steerage (or nudging) toward choices that augment their well-being. Deciphering what constitutes "good" emerges as a multifaceted matter, extensively tackled within the book. The underlying guiding principle is to direct toward avenues of maximum benefit while minimizing the risk of harm. Should professed intentions diverge from actions due to human proclivities, the paternalistic liberal stance involves offering aid and nudging back onto the right path. An unembellished example, as embodied by President Barack Obama, involves instituting initiatives to combat obesity in schools. Why is this necessary despite aligning with human desires? Because our human nature is strewn with biases that lead to irrational conduct (as expounded in Kahneman's "Thinking, Fast and Slow"): a penchant for immediate gains over long-term repercussions, avoidance of intricate actions, and aversion to decisions that appear convoluted. Notably, NUDGE proves considerably more lenient than rigid mandates and obligations.

NUDGE tools are far from arbitrary; they find their roots in our biases, encompassing representation, availability, heuristics, commitment to sustainability, framing, and beyond. These biases frequently propel us to act illogically, and NUDGE tools are fashioned to counteract these tendencies. The authors advocate the judicious employment of these tools where intervention is warranted.

The society encompassing us exerts an influence over our actions. Why does this occur? In most instances, we tend to conform and assimilate. Operating within these principles involves:

Providing information about actions taken by others.

Remaining within a group where colleagues hold sway.

Garnering people's commitment to step (priming).

NUDGE strategies encompass:

Displaying the percentage of individuals who have already decided or opted for a specific path you aim to promote.

Employing phrases like "More people prefer..."

Conveying the actions others have already embarked upon.

Instilling the expectation that an individual with a favorable opinion will be the first to voice it, thereby encouraging confident and vocal expression.

Inquiring about people's intentions concerning the topic you seek to endorse, solitary discussion can heighten their commitment to acting in that direction.

Examples include:

The "Don't Mess with Texas" campaign, which curbed littering.

Highlighting individuals' significant tax contributions to deter tax evasion.

Contrasting an account holder's power consumption graph with the entire city.

Recommendation:

More than merely informing people that their behavior is above average is required. For instance, presenting a power consumption graph, as depicted above, to those consuming less might trigger an adverse response. However, incorporating a smiling graph emoji alongside it can alleviate this impact. This touch of positive feedback prevents negative shifts in behavior that align with the norm.

The realm of choices can indeed pose challenges for us as users.

Abiding by these principles entails:

Simplifying the decision-making process.

Reducing the number of options presented.

Granting users the freedom to modify their choices effortlessly.

Acknowledging the potential for human fallibility in decision-making.

Default Setting – Establishing a default option aligned with the desired outcome. In scenarios where multiple choices exist, and a universally optimal selection is absent, the default setting is tailored to group affiliation or individual preferences.

Mandatory Selection – Prohibiting progression without opting for one of the alternatives.

Streamlining Choices – Condensing the array of available selections to the essential ones.

Supplying Personalized Supplementary Information to facilitate decision-making.

Illustrations include:

Countries implementing a "positive" default for expressing willingness to donate organs, leading to a notable surge in donor percentages.

Preventing the possibility of inserting a train ticket in the wrong orientation.

Offering information about available schools to ensure well-informed and strategic choices rather than settling for familiar or convenient options.

Recommendations:

When confronted with any choice, meticulous consideration is imperative to determine whether it's prudent to compel the user to decide or if providing a default option proves more suitable. There exists no one-size-fits-all solution...

And always bear in mind – accommodating user-initiated changes made easy.

Implementing intricate processes often proves to be a formidable challenge, frequently resulting in resistance or non-compliance among individuals.

The operational principles encompass:

Recognizing the inherent human tendency to reject complex implementations.

Prioritizing simplicity.

Disseminating knowledge.

Adapting communication to the specific target audience.

Streamlining ostensibly intricate procedures.

Identifying and rectifying common errors.

Decomplicating intricate choices into streamlined, uniform steps.

Simplifying queries and responses related to decision-making.

Furnishing pertinent information to enable personalized decision-making.

Opting for deferred decisions in the present, with automatic implementation in the future.

Enhancing congruence between accompanying symbols and desired actions.

Detecting and averting common errors through feedback and corrective suggestions.

Facilitating correction before, during, and after the process, ensuring adherence to the correct course.

Illustrations include:

Committing to heightened savings as earnings increase.

Preventing sending an email containing the term "attachment" when no file is affixed.

Forwarding a pre-filled tax refund form to an employed individual, necessitating only a signature for return.

Incorporating relevant icons alongside actions or selections.

Introducing a dedicated credit card for donations with automated recognition of tax deductions.

A synergistic relationship exists between supportive measures and the simplification of processes. It is prudent to contemplate these aspects both individually and collectively.

Incentivizing Behaviors

Incentives and pricing stand as the foundational pillars of any free-market economy. Even when applying the NUDGE approach, their significance should always be considered. It remains crucial to ascertain whether incentives, be they positive or negative, can effectively propel individuals into action.

Operational principles encompass:

Customizing incentives for groups or individuals.

Employing a "carrot or stick" paradigm.

Offering insights into available incentives or feasibility.

Spotlighting the costs of inaction or incorrect choices.

Reinforcing or underscoring familiar incentives or feasibility to stimulate decision-making and action.

Alleviating conflicts between pros and cons during the decision-making process.

Fostering feasibility by conveying content that resonates with decision-makers.

Displaying the message "Drink more water. When sweating, the body loses fluids" on pamphlets distributed at sporting events.

Portraying the feasibility of higher education by bridging the gap for high school students, juxtaposing differences between a Mercedes car and a Kia, and prominently featuring registration forms.

The "Turns on Whoever Clicks First" campaign – champions a cultural shift in seat belt usage.

When devising incentives, it is prudent to inquire: Who wields influence over the decision? (Not exclusively the user or payer) Incentive concepts should be tailored accordingly.

Ensure that the incentive is conspicuously displayed and readily noticeable by the decision-maker.

Knowledge intricately weaves into the array of previously expounded NUDGE tools. Nevertheless, a few additional pivotal points warrant emphasis.

Timely dissemination of knowledge.

Tailoring knowledge to the specific context.

Artful framing of knowledge to harmonize with NUDGE objectives.

Concentrating on pertinent knowledge.

Strategically assessing the opportune moment for NUDGE implementation and knowledge delivery.

Seamlessly integrating knowledge alongside choices, responses, and throughout the decision-making process.

Infusing lesser-known information to influence decision considerations.

llustrations include:

Orchestrating gatherings with parents of eighth-grade children to introduce university savings programs.

Mandating the prominent display of graphic fuel efficiency and environmental performance data, complemented by relative positioning based on Ministry of Transport statistics, for comparable vehicles.

Publicly disclosing a blocklist of 100 companies with subpar environmental practices (or in any other sphere).

Appending a "meets the standard" emblem for companies showcasing excellence in specific domains.

Exercise prudence to avoid inundating with an excess of knowledge.

For the authors of this book, the task of delivering a conscientious nudge while upholding a liberal perspective is a formidable challenge. This nuanced approach reverberates throughout the book, manifesting in explicit assertions and the curation of subjects warranting NUDGE implementation. Yet, the authors do not shy away from addressing potential objections and furnishing their counterarguments:

Slippery Slope

Concern: Instigating NUDGE in appropriate contexts might inadvertently pave the way for its application in less fitting scenarios.

Response: While this is a valid consideration, the drawbacks of abstaining from NUDGE outweigh the associated risks. Furthermore, the provision for effortless decision reversal acts as a protective measure against potential harm.

Problem with Choice Architects

Concern: Apprehensions arise regarding potential bias in those executing NUDGE, favoring choices aligned with their agendas.

Response: Transparency, to the maximum extent, is imperative. Upholding freedom of choice, even in the presence of bias, helps mitigate this concern.

The Right to Make Mistakes

Concern: The discourse revolves around individuals' entitlement to make choices, even if not inherently advantageous, potentially resulting in uniformity in erroneous decisions.

Response: Just as we wouldn't thrust children into deep waters due to the universality of mistakes, assisting people is prudent—especially in matters where their preferences are evident.

Resistance to Bias

Concern: Opposition may arise against intervention, even when the intervention aligns with the correct course.

Response: Tackle resistance with perseverance. Pursuing a legitimate goal remains justified.

Neutrality of Concern

Concern: Governments or public entities should maintain impartiality.

Response: In instances of providing assistance rather than harm to individuals, unswerving neutrality is not an absolute mandate.

The authors adeptly navigate these objections, striking an artful equilibrium between guided influence and preserving individual autonomy within a liberal framework.

- Change Managment

- Book reviews

Recent Posts

The E-Myth- Book Review

Change Management - Hope or Reality?

Whole Thought: The Rise of Human Intelligence- Book Review

QuestionsPresented

Book review: nudge.

The book is concerned with the way people deal with choices in their lives. The authors refer to an arrangement of options– for example, the layout of a food buffet– as choice architecture. Choice architecture is manipulable, and choice architects have the ability to control decision making in a meaningful way through the presentation and arrangement of options. “Humans predictably err,” and, by understanding these cognitive biases, choice architects can shape outcomes. Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness 7 (Penguin Books 2009) (2008). There is an entire set of studies and literature on cognitive biases that is emerging, particularly in the behavioral economics literature. Examples include confirmation bias , self-serving bias , and anchoring bias . A detailed exploration of these and other cognitive biases is beyond the scope of the book and this post. What is important for Thaler and Sunstein is that everyone has these systematic biases. Also important to Nudge is pointing out the “misconception…that it is possible to avoid influencing people’s choices”; in other words, there is no such thing as neutral choice architecture. Id. at 10; see also id. at 249-51 (discussing different types of neutrality and situations in which neutrality may be possible). Intended or not, every arrangement of options has an effect on those faced with the options.

The core of Nudge ‘s contribution is an approach to choice architecture (which also could be thought of as system organization) the authors call “libertarian paternalism.” As the authors explain:

Libertarian paternalists urge that people should be free to choose. We strive to design policies that maintain or increase freedom of choice. When we use the term libertarian to modify the word paternalism , we simply mean liberty-preserving….Libertarian paternalists want to make it easy for people to go their own way; they do not want to burden those who want to exercise their freedom. The paternalistic aspect lies in the claim that it is legitimate for choice architects to try to influence people’s behavior in order to make their lives longer, healthier, and better. In other words, we argue for self-conscious efforts, by institutions in the private sector and also by government, to steer people’s choices in directions that will improve their lives. In our understanding, a policy is “paternalistic” if it tries to influence choices in a way that will make choosers better off, as judged by themselves .

Id. at 5 (quotation marks omitted). Thaler and Sunstein call this influencing “nudging”:

A nudge…is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting the fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.

Id. at 6. The authors acknowledge that “some of our nudges do, in a sense, impose cognitive (rather than material) costs, and in that sense alter incentives,” but argue that “nudges count as such, and qualify as libertarian paternalism, only if any costs are low.” Id. at 8.

Much of the book covers case studies showing nudging in action or how the greater use of effective choice architecture could improve outcomes for people. These examples include saving money, financial investment, the privatization of social security, prescription drug plans, organ donation policies, environmental conservation, school choice, health care, and marriage policy. While I’m not sure that Thaler and Sustein’s proposal for a “privatization” of marriage in which states only issue civil unions fits neatly within this book’s framework, I do think it could make a good topic for a future post here. If you are especially interested in these and the many other examples of nudges, the revised edition of the book or the authors’ regularly updated blog are good places to look.

Near the end of the book, the authors respond to certain objections to their approach. The first objection is that of the classic slippery slope : if we permit this limited paternalistic intervention, it won’t be long before government overreaches, and “highly intrusive interventions will surely follow.” Id. at 239. Thaler and Sunstein have substantive and structural responses to this objection: first, they would prefer this sort of critic to engage with them as to the merits of the chosen policy preferences rather than the structure itself, and second, this sort of structure is inevitable: “It is pointless to ask government simply to stand aside. Choice architects, whether private or public, must do something .” Id. at 240. They continue:

Those who make this argument sometimes speak as if government can be absent– as if the default terms that set the background come from nature or from the sky. This is a big mistake. To be sure, the default terms that now apply in any particular context might be best…. But that view must be defended, not assumed. And it would be odd for those who generally hold government in extremely low esteem to think that in all domains, past governments have somehow stumbled onto a set of ideal arrangements.

Id. at 241. Thaler and Sustein also do not think that a traditionalist, Burkean response based on the wisdom of longstanding social practices has much value here because “inertia, procrastination, and imitation often drive our behavior.” Id.

A second objection is that choice architects may have their own agendas, the implication being that these agendas could be “evil” or otherwise not in people’s best interest. Recognizing “that choice architects in all walks of life have incentives to nudge people in directions that benefit the architects…rather than the users,” the authors nevertheless believe that “lin[ing] up incentives when we can, and employ[ing] monitoring and transparency when we can’t” will be sufficient to overcome this issue. Id. at 242. Freedom of choice and transparency are important in this area. Related is John Rawls’ publicity principle: “In its simplest form, the publicity principle bans government from selecting a policy that it would not be able or willing to defend publicly to its own citizens.” Id. at 247. This would prohibit secrecy on the part of the government when it alters legal default rules, for example.

Thaler and Sunstein present and respond to other objections, but, at this point, I would like to both encourage readers to include their questions and critiques in the comment section below and offer my own thoughts.

Second, I think the second objection I mentioned above– a concern over the goodness of the intentions of choice architects– is a serious one that the authors fail to rebut sufficiently. Anyone who spends time studying cognitive biases and systematic human behavior should be able to take that knowledge and design a system that preferences any particular outcome, even ones that are not “beneficial” to users. Thaler and Sunstein recognize, through the myriad examples they cite throughout their book, that this happens all the time; they simply chalk it up to bad choice architecture and poor nudging. This might very well be the case in the examples they chose. The “bad” outcomes there could be a result of a lack of organization, planning, awareness, knowledge, or forethought. But what if similarly “bad” outcomes resulted from a knowledgeable, organized, aware choice architect and choice architecture? Freedom of choice and transparency might help here, but there seems to be no special reason why they should. An early example in the book is a school cafeteria in which a choice architect may organize food in a way that makes students more likely to choose fruits and vegetables and less likely to choose junk food. The reason this works has nothing to do with the nature of the fruits and vegetables (or that nature vis-a-vis the students) and everything to do with the systematic biases of the students themselves. So long as the libertarian constraint is in place, the students can choose whatever they want, but the paternalistic element permits the choice architect to select any option as the preferred option. Fruit, vegetables, and junk food are mere variables in this arrangement. (In political theory terms, the structure here is largely deontological, the right to define “the good” resting solely with the choice architect.) Additionally, Thaler and Sunstein place no duties on the choice architect in his or her selection of the “good” alternative. An obvious one might be a duty to be informed. The cafeteria administrator might have some idea that fruits and vegetables are healthier than junk food, but we also are told that dark chocolate and red wine (though not for children) have health benefits too. How should one evaluate this particular tradeoff, and how should one evaluate it against all of the dietary decisions that go into putting together a balanced meal? Does a “balanced meal” mean the same thing for every student? For a majority of students?

An architect

I think concerns about the qualifications and motivations of choice architects are greater than Thaler and Sunstein admit, and, if nothing else, deserved a more adequate defense. Overall, though, I am glad I read the book, and I think it does a good job of spurring discourse. Irrespective of whether you’ve read Nudge , I welcome your thoughts below.

Share this:

I admire the clarity of your writing. You obviously keep your eye on what you want to say and express it without ambiguity, something I could do more often in my own writing (although ambiguity has its place). Reading your review, I was struck by a vision of millions of choice architects (advertisers, government officials, lobbyists, politicians, families, individuals) all trying to nudge us in a million different ways. On the receiving end, it becomes a challenge to maintain your own beliefs and navigational system and meet all your daily responsibilities. But that’s part of living in a pluralistic society, and essentially what shapes our personalities–the give and take with other people on this planet.

I also wondered how you feel about initiatives that go beyond nudging–take laws, for example. Is something more than a nudge necessarily a bad thing?

Thank you, and thanks for reading. To respond to your question, I think laws are, for the most part, a different animal. Under the Thaler & Sunstein approach, nudges are useful to governments or societies because they are tools to advance social policy in areas where command and control regulation is less desirable. Environmental policy is a good example because it lately tends to be a polarized area politically. For the authors, nudges must meet the libertarian paternalism requirements (costless ability to choose alternatives), so a nudge in this area toward greener practices would be a way to advance those aims that is less objectionable to opponents because they could opt out at low or no cost.

Much of nudging has to do with the setting of default rules. Parties always can bargain around default rules (and libertarian paternalism requires the cost of that bargaining to be negligible), but the setting of the default rules is important because people tend to just accept whatever terms are presented to them, even when they are not what they would choose given a blank slate (basically an inertia notion). The crux of this line of thinking is that if you can create favorable defaults, the desired result will obtain in more instances because people who are indifferent or uninformed will select that result because they don’t know or don’t care, and at least some who are opposed might still select your result because it’s easier to do. A very simple example is a motion-activated paper towel dispenser in a restroom. If the establishment manager wanted to limit paper towel consumption, he could reduce the length of paper towel that spooled out after a hand wave. (Of course, successful default rule setting probably requires some research. For example, if he sets the length too short, too many people might wave for a second or third piece.) Back to the realm of controversial political areas, hospital administrators could require doctors to ask newly pregnant patients a question about the possibility of aborting the pregnancy. The choice always would belong with the woman, but the question, merely by being asked, is likely to influence that choice. (Notably, the influence could go either direction. Cf. “Are you aware of the physical, mental, and ethical dangers of having an abortion?” with “Have you considered having an abortion in light of the substantial responsibilities that come with raising a child?”)

Getting back to your question, there are different sorts of laws. The laws I think you’re asking about are of a regulatory variety. In that case, nudges and laws could be understood as being situated along a spectrum. My interpretation of the Thaler & Sunstein view described in this comment is that nudges can advance policy objectives in areas where it is too politically difficult to do so with a legal edict. We might favor a legal approach where we think the nudge will be insufficient to result in meaningful levels of complying behavior with the chosen goal, or where the dangers of not complying are very high. We do this sort of command and control regulation with some frequency, and not everybody likes it, which probably is the impetus for the authors’ attempt at a compromise approach. (Another sort of laws work not at advancing social policies but toward protecting individual rights and liberties. I think one can have an opinion on criminal laws and civil rights laws mostly independent of one’s opinion of approaches to regulation.)

Once we say that it’s appropriate to do some command and control regulating, we face a new set of questions, including who should do the regulating (e.g., federal vs. state government, public vs. private institutions) and on what basis. The book’s contribution comes in raising an alternative to the familiar approach. Some think that there is a certain amount of paternalism inherent even in the concept and existence of government. It is hard to see how a government could function without exercising power through means more forceful than nudges. After reading all of Nudge, I’m confident that Thaler & Sunstein believe that there are some, perhaps many, areas in which nudging is inappropriate because it would be insufficient. One of their points, as I read them, is that there are some, perhaps many, areas in which something less paternalistic will work just fine.

- No trackbacks yet.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Email subscription.

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Subscribe by email

Topic Browser

Latest comments.

- life Skills Coaching on Book Review: I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition

- good coachi on Book Review: I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition

- Self improvement on Law “School”: Education or Professional Filtering?

- A Kaleidoscoped Life

- Andy Mention

- Brand Catharsis

- Bridging the Gap

- Free Lunches

- House of Bland and Blog

- House Rules

- Jackalope Brewing

- Jazz Backstory

- Law School Transparency

- Legal Theory Blog

- Mass Tort Litigation Blog

- Pastured Poetry

- Run for the Fallen

- Rustic Eats & Uniques

- Sixth Circuit Appellate Blog

- Sixth Circuit Immigration Decisions

- Tasty Gnarl

- The Alexander Hamilton Institute

- The Intercept

- The Volokh Conspiracy

- TODDJHARTLEY

- Vanderbilt Sports Line

TweeterCenter

- An error has occurred; the feed is probably down. Try again later.

From the Web

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

books that slay

book summaries & discussion guides

Nudge Summary and Key Lessons | Richard H. Thaler

“Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health , Wealth, and Happiness” is a book by economist Richard H. Thaler and legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein, published in 2008.

Quick Summary: The book popularized the concept of “nudge theory,” which suggests that positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions can significantly influence people’s behavior and decision-making processes in a way that is beneficial to them, without restricting their freedom of choice at any cost.

Nudge Full Summary

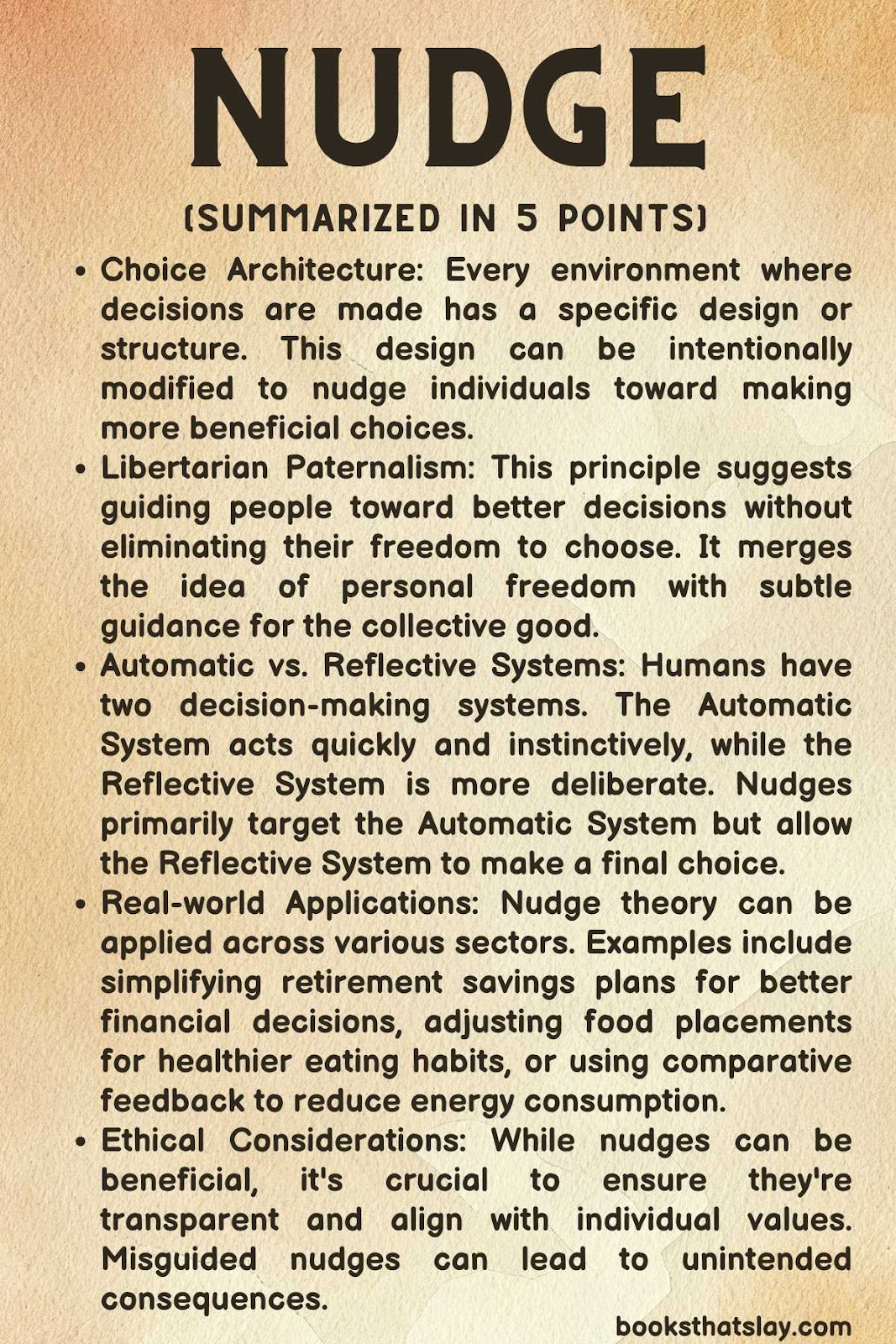

Choice architecture.

At the heart of the book is the concept of “choice architecture,” which refers to the design of environments in which people make choices.

Choice architects, like policymakers or designers of systems and processes, have the ability to structure these environments in ways that “nudge” people toward making better decisions.

Thaler and Sunstein argue that choice architecture is inevitable because some design has to exist, whether it’s carefully considered or not.

So, they contend, why not design it in a way that helps people?

Libertarian Paternalism

Thaler and Sunstein introduce the notion of “libertarian paternalism,” combining elements of libertarianism (freedom of choice) and paternalism (making decisions for the greater good of others).

The idea is to steer people in beneficial directions while still maintaining their freedom to choose.

They stress that nudges are not mandates. People remain free to go their own way, but the choice architecture makes the beneficial option more salient or easier to choose.

Automatic vs. Reflective Systems

Drawing on dual-system theories in psychology , the authors discuss two types of thinking: the “Automatic System,” which is fast, instinctive, and emotional; and the “Reflective System,” which is slower, more deliberate, and logical.

Nudges primarily aim to guide our Automatic System in the right direction while still leaving the Reflective System free to opt out or choose otherwise.

Real-world Applications

The book dives into a range of real-world applications, exploring how nudges can be used to make improvements in various aspects of society:

- Personal Finance : Simplifying the process of enrollment and selection in retirement savings plans can help people save more and make better investment choices.

- Health : Placing healthier foods at eye level in school cafeterias can nudge kids to make healthier eating choices.

- Energy Conservation : Giving people feedback about their energy usage compared to their neighbors can encourage them to use less energy.

- Government Policies : Making enrollment in public assistance programs simpler or default can nudge more eligible people to take advantage of them.

- Organ Donation : Switching from an opt-in to an opt-out system can significantly increase the number of organ donors.

Ethical Considerations

Thaler and Sunstein also address the ethical concerns surrounding nudging. They argue that since choice architecture is unavoidable, it’s better to design it in a transparent and beneficial manner. They advocate for “nudges” that are consistent with people’s values and that aim to improve their lives by their own standards.

However, they caution that poorly-designed nudges can have unintended consequences, and there are limits to what nudges can accomplish.

The authors conclude by urging professionals and policymakers to be mindful choice architects, leveraging the power of nudges to make it easier for people to make decisions that will benefit them.

The book has been highly influential, leading to the application of nudge theory in various fields such as public policy, economics , and healthcare. It has also inspired the establishment of “nudge units” in governments around the world, designed to apply behavioral insights to policy-making.

Also Read: The Innovator’s Dilemma Summary and Key Lessons

Key Lessons

1. the power of default options.

One of the most profound insights from “Nudge” is how potent default options can be. People tend to go with the flow of pre-set options, mainly because of inertia, a desire to avoid complicated decisions, or the assumption that the default is somehow endorsed or recommended.

Consider the example of organ donations.

Countries with an opt-out system (where citizens are default donors unless they choose not to be) have dramatically higher donation rates compared to those with an opt-in system.

Similarly, automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans significantly boosts participation rates.

Why it Matters ?

Recognizing the power of defaults can be used both to shape behavior for the collective good and to protect individuals from potential exploitation. Marketers, service providers, or software designers often set defaults that benefit them more than the end user.

Being aware of this can lead to more informed decisions.

Application : Whether you’re a policy designer aiming to encourage a particular behavior or an individual navigating choices, always consider the default settings. They either serve as a powerful tool for nudging in the desired direction or a potential pitfall if left unexamined.

2. Importance of Simplifying Choices

The book emphasizes that people can get overwhelmed when presented with too many choices or with overly complicated decisions. This can lead to decision paralysis or suboptimal choices.

For example, in the domain of personal finance, many employees avoid participating in retirement saving plans because the choices (which funds to pick, how much to invest, etc.) are too complex.

By simplifying the decision process or offering clearer guidance, participation can increase, and better financial outcomes can be achieved.

Complexity can be a barrier. By simplifying choices or processes, you can improve engagement, comprehension, and outcomes.

For individuals, understanding the need for simplicity can help in breaking down tasks or decisions into manageable steps, avoiding unnecessary complications.

Application : Whether designing a user interface, creating a policy, or setting personal goals, focus on clarity and simplicity. Reducing cognitive load can lead to more consistent and positive actions.

Also Read: The Mountain is You Summary and Key Lessons

3. Transparency and Ethical Nudging

Not all nudges are created equal.

While many nudges can steer people toward better outcomes, they can also be used manipulatively. The authors stress the importance of transparency and ensuring that nudges are implemented ethically.

Consider the design of a supermarket.

Placing sugary cereals at eye level for children might increase sales (a nudge), but it’s arguably not in the best interest of the children or their parents from a health perspective.

Ethical considerations ensure that nudges are aligned with the genuine well-being and preferences of those being nudged. Transparent practices ensure that individuals are aware of how choices are being presented to them and can therefore make informed decisions.

Application : If you’re in a position to design systems or choices for others (as a business owner, policymaker, or manager), always evaluate the ethical implications of your designs.

Are you helping individuals make better decisions by their standards, or are you manipulating them for personal gain?

As a consumer or participant, be mindful of how choices are presented and question the motives behind the design.

Final Thoughts

“Nudge” presents an insightful look into the interplay between behavior, decision-making, and subtle external influences. By shedding light on how simple tweaks can produce significant outcomes, Thaler and Sunstein provide a blueprint for policymakers, business leaders , and individuals to foster better decisions in various spheres of life.

It’s a must-read for those intrigued by behavioral economics and its implications for society.

Read our other summaries

- Before We Were Yours Summary and Key Lessons

- A Court of Frost and Starlight Summary and Key Lessons

- First Break All The Rules Summary and Key Lessons

- All About Love Summary and Key Lessons | Bell Hooks

- How to Read Literature Like a Professor Summary and Key Lessons

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Indicator from Planet Money

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Nudge Vs Shove: A Conversation With Richard Thaler

Greg Rosalsky

Stacey Vanek Smith

Richard Thaler is one of the most important behavioral economists in the world. The Nobel Prize laureate has written extensively on behavioral economics, such as how to get people to save more for retirement. His book, with coauthor Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness has sold millions of copies worldwide and influenced governments and companies alike.

The book challenges the notion that humans are absolutely rational in their decision making, a widely accepted model in economics for years. Instead, Thaler and Sunstein show that the decision making process can be heavily influenced for our benefit, sometimes by very small nudges. In the new and final edition of Nudge , they include a lot of new material. One notable concept is called "sludge", or ways to prevent something from happening by making it incredibly difficult to do. One real world example, according to Thaler, is the American tax filing system.

Music by Drop Electric . Find us: Twitter / Facebook / Newsletter .

Subscribe to our show on Apple Podcasts , Spotify , PocketCasts and NPR One .

- behavioral economics

- decision making

- richard thaler

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness

B elief in the existence of free will ebbs further with every page of Nudge. It couldn't be more timely: in an era in which a vast range of options paralyses decision-makers, this witty unpacking of what the authors call "choice architecture" gives an insight into what influences people when they are faced with a decision. It's fascinating but also a little alarming. The authors, distinguished academics in Economics and Law at the University of Chicago, nimbly convey difficult principles through plenty of palatable examples. Nudge is never intimidating, always amusing and elucidating: a jolly economic romp but with serious lessons within.

- Society books

- The Observer

Most viewed

Select your cookie preferences

We use cookies and similar tools that are necessary to enable you to make purchases, to enhance your shopping experiences and to provide our services, as detailed in our Cookie notice . We also use these cookies to understand how customers use our services (for example, by measuring site visits) so we can make improvements.

If you agree, we'll also use cookies to complement your shopping experience across the Amazon stores as described in our Cookie notice . Your choice applies to using first-party and third-party advertising cookies on this service. Cookies store or access standard device information such as a unique identifier. The 96 third parties who use cookies on this service do so for their purposes of displaying and measuring personalized ads, generating audience insights, and developing and improving products. Click "Decline" to reject, or "Customise" to make more detailed advertising choices, or learn more. You can change your choices at any time by visiting Cookie preferences , as described in the Cookie notice. To learn more about how and for what purposes Amazon uses personal information (such as Amazon Store order history), please visit our Privacy notice .

- Business, Finance & Law