- Programs & Services

- Delphi Center

Ideas to Action (i2a)

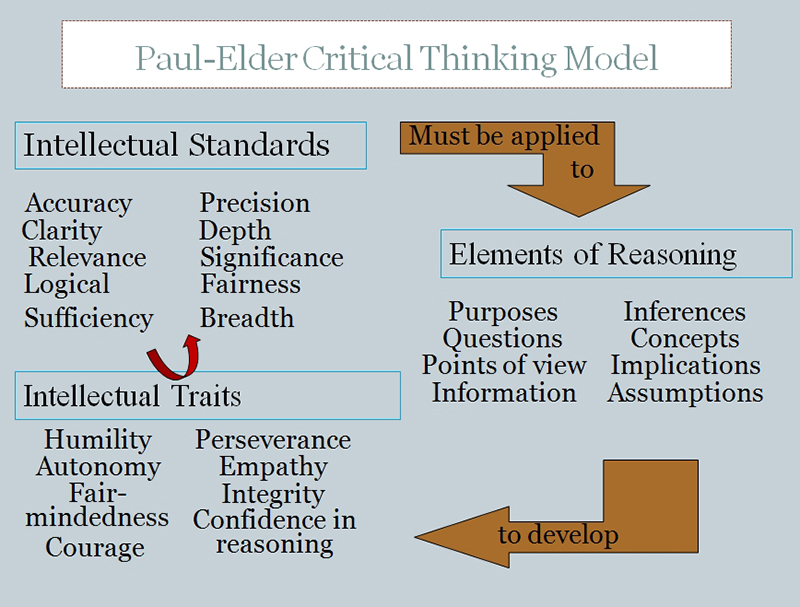

- Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them. (Paul and Elder, 2001). The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought

According to Paul and Elder (1997), there are two essential dimensions of thinking that students need to master in order to learn how to upgrade their thinking. They need to be able to identify the "parts" of their thinking, and they need to be able to assess their use of these parts of thinking.

Elements of Thought (reasoning)

The "parts" or elements of thinking are as follows:

- All reasoning has a purpose

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem

- All reasoning is based on assumptions

- All reasoning is done from some point of view

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequences

Universal Intellectual Standards

The intellectual standards that are to these elements are used to determine the quality of reasoning. Good critical thinking requires having a command of these standards. According to Paul and Elder (1997 ,2006), the ultimate goal is for the standards of reasoning to become infused in all thinking so as to become the guide to better and better reasoning. The intellectual standards include:

Intellectual Traits

Consistent application of the standards of thinking to the elements of thinking result in the development of intellectual traits of:

- Intellectual Humility

- Intellectual Courage

- Intellectual Empathy

- Intellectual Autonomy

- Intellectual Integrity

- Intellectual Perseverance

- Confidence in Reason

- Fair-mindedness

Characteristics of a Well-Cultivated Critical Thinker

Habitual utilization of the intellectual traits produce a well-cultivated critical thinker who is able to:

- Raise vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely

- Gather and assess relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively

- Come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2010). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

- SACS & QEP

- Planning and Implementation

- What is Critical Thinking?

- Why Focus on Critical Thinking?

- Culminating Undergraduate Experience

- Community Engagement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is i2a?

Copyright © 2012 - University of Louisville , Delphi Center

We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

Intellectual humility: the importance of knowing you might be wrong

Why it’s so hard to see our own ignorance, and what to do about it.

by Brian Resnick

Illustrations by Javier Zarracina

Julia Rohrer wants to create a radical new culture for social scientists. A personality psychologist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Rohrer is trying to get her peers to publicly, willingly admit it when they are wrong.

To do this, she, along with some colleagues, started up something called the Loss of Confidence Project. It’s designed to be an academic safe space for researchers to declare for all to see that they no longer believe in the accuracy of one of their previous findings. The effort recently yielded a paper that includes six admissions of no confidence. And it’s accepting submissions until January 31 .

“I do think it’s a cultural issue that people are not willing to admit mistakes,” Rohrer says. “Our broader goal is to gently nudge the whole scientific system and psychology toward a different culture,” where it’s okay, normalized, and expected for researchers to admit past mistakes and not get penalized for it.

The project is timely because a large number of scientific findings have been disproven, or become more doubtful, in recent years. One high-profile effort to retest 100 psychological experiments found only 40 percent replicated with more rigorous methods. It’s been a painful period for social scientists, who’ve had to deal with failed replications of classic studies and realize their research practices are often weak.

“Not knowing the scope of your own ignorance is part of the human condition”

It’s been fascinating to watch scientists struggle to make their institutions more humble. And I believe there’s an important and underappreciated virtue embedded in this process.

For the past few months, I’ve been talking to many scholars about intellectual humility, the characteristic that allows for admission of wrongness.

I’ve come to appreciate what a crucial tool it is for learning, especially in an increasingly interconnected and complicated world. As technology makes it easier to lie and spread false information incredibly quickly , we need intellectually humble, curious people.

I’ve also realized how difficult it is to foster intellectual humility. In my reporting on this, I’ve learned there are three main challenges on the path to humility:

- In order for us to acquire more intellectual humility, we all, even the smartest among us, need to better appreciate our cognitive blind spots. Our minds are more imperfect and imprecise than we’d often like to admit. Our ignorance can be invisible.

- Even when we overcome that immense challenge and figure out our errors, we need to remember we won’t necessarily be punished for saying, “I was wrong.” And we need to be braver about saying it. We need a culture that celebrates those words.

- We’ll never achieve perfect intellectual humility. So we need to choose our convictions thoughtfully.

This is all to say: Intellectual humility isn’t easy. But damn, it’s a virtue worth striving for, and failing for, in this new year.

Intellectual humility, explained

Intellectual humility is simply “the recognition that the things you believe in might in fact be wrong,” as Mark Leary , a social and personality psychologist at Duke University, tells me.

But don’t confuse it with overall humility or bashfulness. It’s not about being a pushover; it’s not about lacking confidence, or self-esteem. The intellectually humble don’t cave every time their thoughts are challenged.

Instead, it’s a method of thinking. It’s about entertaining the possibility that you may be wrong and being open to learning from the experience of others. Intellectual humility is about being actively curious about your blind spots. One illustration is in the ideal of the scientific method, where a scientist actively works against her own hypothesis, attempting to rule out any other alternative explanations for a phenomenon before settling on a conclusion. It’s about asking: What am I missing here?

It doesn’t require a high IQ or a particular skill set. It does, however, require making a habit of thinking about your limits, which can be painful. “It’s a process of monitoring your own confidence,” Leary says.

When I open myself up to the vastness of my own ignorance, I can’t help but feel a sudden suffocating feeling

This idea is older than social psychology. Philosophers from the earliest days have grappled with the limits of human knowledge. Michel de Montaigne, the 16th-century French philosopher credited with inventing the essay, wrote that “the plague of man is boasting of his knowledge.”

Social psychologists have learned that humility is associated with other valuable character traits: People who score higher on intellectual humility questionnaires are more open to hearing opposing views . They more readily seek out information that conflicts with their worldview. They pay more attention to evidence and have a stronger self-awareness when they answer a question incorrectly.

When you ask the intellectually arrogant if they’ve heard of bogus historical events like “Hamrick’s Rebellion,” they’ll say, “Sure.” The intellectually humble are less likely to do so. Studies have found that cognitive reflection — i.e., analytic thinking — is correlated with being better able to discern fake news stories from real ones. These studies haven’t looked at intellectual humility per se, but it’s plausible there’s an overlap.

Most important of all, the intellectually humble are more likely to admit it when they are wrong. When we admit we’re wrong, we can grow closer to the truth.

The world needs more wonder

The Unexplainable newsletter guides you through the most fascinating, unanswered questions in science — and the mind-bending ways scientists are trying to answer them. Sign up today .

One reason I’ve been thinking about the virtue of humility recently is because our president, Donald Trump, is one of the least humble people on the planet.

It was Trump who said on the night of his nomination, “I alone can fix it,” with the “it” being our entire political system. It was Trump who once said, “ I have one of the great memories of all time .” More recently, Trump told the Associated Press, “I have a natural instinct for science,” in dodging a question on climate change.

A frustration I feel about Trump and the era of history he represents is that his pride and his success — he is among the most powerful people on earth — seem to be related. He exemplifies how our society rewards confidence and bluster, not truthfulness.

Yet we’ve also seen some very high-profile examples lately of how overconfident leadership can be ruinous for companies. Look at what happened to Theranos, a company that promised to change the way blood samples are drawn. It was all hype, all bluster, and it collapsed. Or consider Enron’s overconfident executives, who were often hailed for their intellectual brilliance — they ran the company into the ground with risky, suspect financial decisions.

The problem with arrogance is that the truth always catches up. Trump may be president and confident in his denials of climate change, but the changes to our environment will still ruin so many things in the future.

Why it’s so hard to see our blind spots: “Our ignorance is invisible to us”

As I’ve been reading the psychological research on intellectual humility and the character traits it correlates with, I can’t help but fume: Why can’t more people be like this?

We need more intellectual humility for two reasons. One is that our culture promotes and rewards overconfidence and arrogance (think Trump and Theranos, or the advice your career counselor gave you when going into job interviews). At the same time, when we are wrong — out of ignorance or error — and realize it, our culture doesn’t make it easy to admit it. Humbling moments too easily can turn into moments of humiliation.

So how can we promote intellectual humility for both of these conditions?

In asking that question of researchers and scholars, I’ve learned to appreciate how hard a challenge it is to foster intellectual humility.

First off, I think it’s helpful to remember how flawed the human brain can be and how prone we all are to intellectual blind spots. When you learn about how the brain actually works, how it actually perceives the world, it’s hard not to be a bit horrified, and a bit humbled.

We often can’t see — or even sense — what we don’t know. It helps to realize that it’s normal and human to be wrong.

It’s rare that a viral meme also provides a surprisingly deep lesson on the imperfect nature of the human mind. But believe it or not, the great “Yanny or Laurel” debate of 2018 fits the bill.

For the very few of you who didn’t catch it — I hope you’re recovering nicely from that coma — here’s what happened.

An audio clip (you can hear it below) says the name “Laurel” in a robotic voice. Or does it? Some people hear the clip and immediately hear “Yanny.” And both sets of people — Team Yanny and Team Laurel — are indeed hearing the same thing.

Hearing, the perception of sound, ought to be a simple thing for our brains to do. That so many people can listen to the same clip and hear such different things should give us humbling pause. Hearing “Yanny” or “Laurel” in any given moment ultimately depends on a whole host of factors: the quality of the speakers you’re using, whether you have hearing loss, your expectations.

Here’s the deep lesson to draw from all of this: Much as we might tell ourselves our experience of the world is the truth, our reality will always be an interpretation. Light enters our eyes, sound waves enter our ears, chemicals waft into our noses, and it’s up to our brains to make a guess about what it all is.

“The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club”

Perceptual tricks like this ( “the dress” is another one) reveal that our perceptions are not the absolute truth, that the physical phenomena of the universe are indifferent to whether our feeble sensory organs can perceive them correctly. We’re just guessing. Yet these phenomena leave us indignant: How could it be that our perception of the world isn’t the only one?

That sense of indignation is called naive realism: the feeling that our perception of the world is the truth. “I think we sometimes confuse effortlessness with accuracy,” Chris Chabris , a psychological researcher who co-authored a book on the challenges of human perception, tells me . When something is so immediate and effortless to us — hearing the sound of “Yanny” — it just feels true . (Similarly, psychologists find when a lie is repeated, it’s more likely to be misremembered as being true , and for a similar reason: When you’re hearing something for the second or third time, your brain becomes faster to respond to it. And that fluency is confused with truth.)

Our interpretations of reality are often arbitrary, but we’re still stubborn about them. Nonetheless, the same observations can lead to wildly different conclusions.

(Here’s that same sentence in GIF form.)

For every sense and every component of human judgment, there are illusions and ambiguities we interpret arbitrarily.

Some are gravely serious. White people often perceive black men to be bigger, taller, and more muscular (and therefore more threatening ) than they really are. That’s racial bias — but it’s also a socially constructed illusion. When we’re taught or learn to fear other people, our brains distort their potential threat. They seem more menacing, and we want to build walls around them. When we learn or are taught that other people are less than human , we’re less likely to look upon them kindly and more likely to be okay when violence is committed against them.

Not only are our interpretations of the world often arbitrary, but we’re often overconfident in them. “Our ignorance is invisible to us,” David Dunning, an expert on human blind spots, says.

You might recognize his name as half of the psychological phenomenon that bears his name: the Dunning-Kruger effect. That’s where people of low ability — let’s say, those who fail to understand logic puzzles — tend to unduly overestimate their abilities. Inexperience masquerades as expertise.

An irony of the Dunning-Kruger effect is that so many people misinterpret it, are overconfident in their understanding of it, and get it wrong.

When people talk or write about the Dunning-Kruger effect, it’s almost always in reference to other people. “The fact is this is a phenomenon that visits all of us sooner or later,” Dunning says. We’re all overconfident in our ignorance from time to time. (Perhaps related: Some 65 percent of Americans believe they’re more intelligent than average, which is wishful thinking.)

Similarly, we’re overconfident in our ability to remember. Human memory is extremely malleable, prone to small changes. When we remember, we don’t wind back our minds to a certain time and relive that exact moment, yet many of us think our memories work like a videotape.

Dunning hopes his work helps people understand that “not knowing the scope of your own ignorance is part of the human condition,” he says. “But the problem with it is we see it in other people, and we don’t see it in ourselves. The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club.”

People are unlikely to judge you harshly for admitting you’re wrong

In 2012, psychologist Will Gervais scored an honor any PhD science student would covet: a co-authored paper in the journal Science , one of the top interdisciplinary scientific journals in the world. Publishing in Science doesn’t just help a researcher rise up in academic circles; it often gets them a lot of media attention too.

One of the experiments in the paper tried to see if getting people to think more rationally would make them less willing to report religious beliefs. They had people look at a picture of Rodin’s The Thinker or another statue. They thought The Thinker would nudge people to think harder, more analytically. In this more rational frame of mind, then, the participants would be less likely to endorse believing in something as faith-based and invisible as religion, and that’s what the study found. It was catnip for science journalists: one small trick to change the way we think.

“How would I know if I was wrong?” is actually a really, really hard question to answer

But it was a tiny, small-sample study, the exact type that is prone to yielding false positives. Several years later, another lab attempted to replicate the findings with a much larger sample size , and failed to find any evidence for the effect.

And while Gervais knew that the original study wasn’t rigorous, he couldn’t help but feel a twinge of discomfort.

“Intellectually, I could say the original data weren’t strong,” he says. “That’s very different from the human, personal reaction to it. Which is like, ‘Oh, shit, there’s going to be a published failure to replicate my most cited finding that’s gotten the most media attention .’ You start worrying about stuff like, ‘Are there going to be career repercussions? Are people going to think less of my other work and stuff I’ve done?’”

Gervais’s story is familiar: Many of us fear we’ll be seen as less competent, less trustworthy, if we admit wrongness. Even when we can see our own errors — which, as outlined above, is not easy to do — we’re hesitant to admit it.

But turns out this assumption is false . As Adam Fetterman , a social psychologist at the University of Texas El Paso, has found in a few studies , wrongness admission isn’t usually judged harshly. “When we do see someone admit that they are wrong, the wrongness admitter is seen as more communal, more friendly,” he says. It’s almost never the case, in his studies, “that when you admit you’re wrong, people think you are less competent.”

Sure, there might be some people who will troll you for your mistakes. There might be a mob on Twitter that converges in order to shame you . Some moments of humility could be humiliating. But this fear must be vanquished if we are to become less intellectually arrogant and more intellectually humble.

Humility can’t just come from within — we need environments where it can thrive

But even if you’re motivated to be more intellectually humble, our culture doesn’t always reward it.

The field of psychology, overall, has been reckoning with a “ replication crisis ” where many classic findings in the science don’t hold up under rigorous scrutiny. Incredibly influential textbook findings in psychology — like the “ ego depletion” theory of willpower or the “ marshmallow test ” — have been bending or breaking.

I’ve found it fascinating to watch the field of psychology deal with this. For some researchers, the reckoning has been personally unsettling. “I’m in a dark place,” Michael Inzlicht, a University of Toronto psychologist, wrote in a 2016 blog post after seeing the theory of ego depletion crumble before his eyes. “Have I been chasing puffs of smoke for all these years?”

“It’s bad to think of problems like this like a Rubik’s cube: a puzzle that has a neat and satisfying solution that you can put on your desk”

What I’ve learned from reporting on the “replication crisis” is that intellectual humility requires support from peers and institutions. And that environment is hard to build.

“What we teach undergrads is that scientists want to prove themselves wrong,” says Simine Vazire , a psychologist and journal editor who often writes and speaks about replication issues. “But, ‘How would I know if I was wrong?’ is actually a really, really hard question to answer. It involves things like having critics yell at you and telling you that you did things wrong and reanalyze your data.”

And that’s not fun. Again: Even among scientists — people who ought to question everything — intellectual humility is hard. In some cases, researchers have refused to concede their original conclusions despite the unveiling of new evidence . (One famous psychologist under fire recently told me angrily , “I will stand by that conclusion for the rest of my life, no matter what anyone says.”)

Psychologists are human. When they reach a conclusion, it becomes hard to see things another way. Plus, the incentives for a successful career in science push researchers to publish as many positive findings as possible.

There are two solutions — among many — to make psychological science more humble, and I think we can learn from them.

One is that humility needs to be built into the standard practices of the science. And that happens through transparency. It’s becoming more commonplace for scientists to preregister — i.e., commit to — a study design before even embarking on an experiment. That way, it’s harder for them to deviate from the plan and cherry-pick results. It also makes sure all data is open and accessible to anyone who wants to conduct a reanalysis.

That “sort of builds humility into the structure of the scientific enterprise,” Chabris says. “We’re not all-knowing and all-seeing and perfect at our jobs, so we put [the data] out there for other people to check out, to improve upon it, come up with new ideas from and so on.” To be more intellectually humble, we need to be more transparent about our knowledge. We need to show others what we know and what we don’t.

And two, there needs to be more celebration of failure, and a culture that accepts it. That includes building safe places for people to admit they were wrong, like the Loss of Confidence Project .

But it’s clear this cultural change won’t come easily.

“In the end,” Rohrer says, after getting a lot of positive feedback on the project, “we ended up with just a handful of statements.”

We need a balance between convictions and humility

There’s a personal cost to an intellectually humble outlook. For me, at least, it’s anxiety.

When I open myself up to the vastness of my own ignorance, I can’t help but feel a sudden suffocating feeling. I have just one small mind, a tiny, leaky boat upon which to go exploring knowledge in a vast and knotty sea of which I carry no clear map.

Why is it that some people never seem to wrestle with those waters? That they stand on the shore, squint their eyes, and transform that sea into a puddle in their minds and then get awarded for their false certainty? “I don’t know if I can tell you that humility will get you farther than arrogance,” says Tenelle Porter, a University of California Davis psychologist who has studied intellectual humility.

Of course, following humility to an extreme end isn’t enough. You don’t need to be humble about your belief that the world is round. I just think more humility, sprinkled here and there, would be quite nice.

“It’s bad to think of problems like this like a Rubik’s cube: a puzzle that has a neat and satisfying solution that you can put on your desk,” says Michael Lynch , a University of Connecticut philosophy professor. Instead, it’s a problem “you can make progress at a moment in time, and make things better. And that we can do — that we can definitely do.”

For a democracy to flourish, Lynch argues, we need a balance between convictions — our firmly held beliefs — and humility. We need convictions, because “an apathetic electorate is no electorate at all,” he says. And we need humility because we need to listen to one another. Those two things will always be in tension.

The Trump presidency suggests there’s too much conviction and not enough humility in our current culture.

“The personal question, the existential question that faces you and I and every thinking human being, is, ‘How do you maintain an open mind toward others and yet, at the same time, keep your strong moral convictions?’” Lynch says. “That’s an issue for all of us.”

To be intellectually humble doesn’t mean giving up on the ideas we love and believe in. It just means we need to be thoughtful in choosing our convictions, be open to adjusting them, seek out their flaws, and never stop being curious about why we believe what we believe. Again, that’s not easy.

You might be thinking: “All the social science cited here about how intellectual humility is correlated with open-minded thinking — what if that’s all bunk?” To that, I’d say the research isn’t perfect. Those studies are based on self-reports, where it can be hard to trust that people really do know themselves or that they’re being totally honest. And we know that social science findings are often upended.

But I’m going to take it as a point of conviction that intellectual humility is a virtue. I’ll draw that line for myself. It’s my conviction.

Could I be wrong? Maybe. Just try to convince me otherwise.

- Future Perfect

Most Popular

- Trump’s biggest fans aren’t who you think

- Conservatives are shocked — shocked! — that Tucker Carlson is soft on Nazis

- There’s a fix for AI-generated essays. Why aren’t we using it?

- Organize your kitchen like a chef, not an influencer

- Has The Bachelorette finally gone too far?

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

Is anything really “cruelty-free”?

February?! Until February?!?! Boeing slip leaves astronauts in limbo.

The privately funded venture will test out new aerospace technology.

Scientific fraud kills people. Should it be illegal?

The case against Medicare drug price negotiations doesn’t add up.

But there might be global consequences.

Intellectual Humility: Definitions, Questions, and Scott O. Lilienfeld as a Case Example

- First Online: 01 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Shauna M. Bowes 4 ,

- Adele Strother 4 ,

- Rachel J. Ammirati 5 &

- Robert D. Latzman 6

690 Accesses

2 Altmetric

In this chapter, we focus on the construct of intellectual humility (IH), which has been of increasing interest in psychological science over the last several years. We identify why IH is an important construct in psychology, review emerging research on its nature and boundaries, and highlight its potential utility in the domain of critical thinking and reasoning. To hopefully make these points come to life, we conclude the chapter with an overview of what we see as a model for IH in science. Specifically, we conclude with an account of how Dr. Scott O. Lilienfeld embodied key aspects of IH in his scientific pursuits, mentorship, and teaching. We see the study of IH as crucial for the future of psychological science and understanding cognitive bias proneness at large.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Intellectual Humility and Owning One’s Limitations

Intellectual Humility, Confidence, and Argumentation

Intellectual humility: beyond the learner paradigm.

IH is sometimes referred to as epistemic humility. Although these two terms can be used interchangeably to some extent, they are not isomorphic. Epistemic humility is an intellectual virtue that (a) fosters rational beliefs, (b) is rooted in scientific methods and attitudes, and (c) is founded upon the notion that most bodies of knowledge are characterized by uncertainty and human bias (see Lilienfeld et al., 2017 ). Hence, epistemic humility is typically more closely tied to philosophies of science than IH.

Alfano, M., Iurino, K., Stey, P., Robinson, B., Christen, M., Yu, F., & Lapsley, D. (2018). Development and validation of a multi-dimensional measure of intellectual humility. PLoS One, 12 , 1–28.

Google Scholar

Bak, W., & Kutnik, J. (2021). Domains of intellectual humility: Self-esteem and narcissism as independent predictors. Personality and Individual Differences, 177 . Advance online publication.

Bowes, S. M., Blanchard, M. C., Costello, T. H., Abramowitz, A. I., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020a). Intellectual humility and between-party animus: Implications for affective polarization in two community samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 88 . Advanced online publication.

Bowes, S. M., Ammirati, R. J., Costello, T. H., Basterfield, C., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020b). Cognitive biases, heuristics, and logical fallacies in clinical practice: A brief field guide for practicing clinicians and supervisors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51 , 435–445.

Article Google Scholar

Bowes, S. M., Costello, T. H., Ma, W., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020c). Looking under the tinfoil hat: Clarifying the personological and psychopathological correlates of conspiracy beliefs. Journal of Personality . Advance online publication.

Bowes, S. M., Costello, T. H., Lee, C., McElroy-Heltzel, S., Davis, D. E., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2021). Stepping outside the echo chamber: Is intellectual humility associated with less political myside bias? . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Advance online publication.

Church, I. M., & Samuelson, P. L. (2017). Intellectual humility: An introduction to the philosophy and science . Bloomsbury.

Book Google Scholar

Costello, T. H., Bowes, S. M., Stevens, S. T., Waldman, I. D., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2021). Clarifying the structure and nature of left-wing authoritarianism . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Personality Processes and Individual Differences.

Davis, D. E., Rice, K., McElroy, S., DeBlaere, C., Choe, E., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Hook, J. N. (2016). Distinguishing intellectual humility and general humility. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11 , 215–224.

Deffler, S. A., Leary, M. R., & Hoyle, R. H. (2016). Knowing what you know: Intellectual humility and judgments of recognition memory. Personality and Individual Differences, 96 , 255–259.

Epstein, S., & O’Brien, E. J. (1985). The person–situation debate in historical and current perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 98 , 513–537.

Fearon, P. A., Götz, F. M., & Good, D. (2020). Pivotal moment for trust in science-don’t waste it. Nature, 580 , 456–457.

Gervais, W. M. (2013). In godlessness we distrust: Using social psychology to solve the puzzle of anti-atheist prejudice. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7 , 366–377.

Haggard, M., Rowatt, W. C., Leman, J. C., Meagher, B., Moore, C., Fergus, T., et al. (2018). Finding middle ground between intellectual arrogance and intellectual servility: Development and assessment of the limitations-owning intellectual humility scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 124 , 184–193.

Hall, M. P., & Raimi, K. T. (2018). Is belief superiority justified by superior knowledge? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76 , 290–306.

Harding, T. P. (2007). Clinical decision-making: How prepared are we? Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1 , 95–104.

Hazlett, A. (2012). Higher-order epistemic attitudes and intellectual humility. Episteme, 9 , 205–223.

Hill, P. C., Lewis Hall, M. E., Wang, D., & Decker, L. A. (2021). Theistic intellectual humility and well-being: Does ideological context matter? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16 , 155–167.

Hodge, A. S., Mosher, D. K., Davis, C. W., Captari, L. E., Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2020). Political humility and forgiveness of a political hurt or offense. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 48 , 142–153.

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Van Tongeren, D. R., Hill, P. C., Worthington, E. L., Jr., Farrell, J. E., & Dieke, P. (2015). Intellectual humility and forgiveness of religious leaders. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 , 499–506.

Hook, J. N., Farrell, J. E., Johnson, K. A., Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, D. E., & Aten, J. D. (2017). Intellectual humility and religious tolerance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12 , 29–35.

Hoyle, R. H., Davisson, E. K., Diebels, K. J., & Leary, M. R. (2016). Holding specific views with humility: Conceptualization and measurement of specific intellectual humility. Personality and Individual Differences, 97 , 165–172.

Huynh, H. P., & Senger, A. R. (2021). A little shot of humility: Intellectual humility predicts vaccination attitudes and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Journal of Applied Social Psychology . Advance online publication.

Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine, 2 .

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22 , 129–146.

Kalmoe, N. P., & Mason, L. (2019). Lethal mass partisanship: Prevalence, correlates, and electoral contingencies . Paper presented at the NCAPSA American Politics Meeting.

Koetke, J., Schumann, K., & Porter, T. (2021). Intellectual humility predicts scrutiny of COVID-19 misinformation . Social Psychological and Personality Science. Advanced online publication.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J. (2017). Intellectual humility and prosocial values: Direct and mediated effects. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12 , 13–28.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Newman, B. (2020). Intellectual humility in the sociopolitical domain. Self and Identity , 1–28.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive intellectual humility scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98 , 209–221.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., Haggard, M. C., LaBouff, J. P., & Rowatt, W. C. (2020). Links between intellectual humility and acquiring knowledge. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15 , 155–170.

Lack, C. (2018, November 14). Energy psychology: An APA-endorsed pseudoscience. Center for Inquiry. https://centerforinquiry.org/blog/energy-psychology-an-apa-endorsed-pseudoscience/ .

Leary, M. R., Diebels, K. J., Davisson, E. K., Jongman-Sereno, K. P., Isherwood, J. C., Raimi, K. T., et al. (2017). Cognitive and interpersonal features of intellectual humility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43 , 793–813.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2018). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment, 25 , 543–556.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2007). Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2 , 53–70.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2010). Can psychology become a science? Personality and Individual Differences, 49 , 281–288.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2012). Public skepticism of psychology: Why many people perceive the study of human behavior as unscientific. American Psychologist, 67 , 111–129.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2013). Is psychopathy a syndrome? Commentary on Marcus, Fulton, and Edens. Personality Disorder: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 4 , 85–86.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2016). How can skepticism do better? Skeptical Inquirer, 40 . Online publication.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017). Psychology’s replication crisis and the grant culture: Righting the ship. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12 , 660–664.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017b). Microaggressions: Strong claims, inadequate evidence. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12 , 138–169.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Microaggression research and application: Clarifications, corrections, and common ground. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15 , 27–37.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020b). Embracing unpopular ideas: Introduction to the special section on heterodox issues in psychology. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 8 , 1–4.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Bowes, S. M. (2018). Intellectual humility: A key priority for psychological research and practice. Psynopsis (Canadian Psychological Association), 3 , 20–21.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Thames, A. D. (2009). Review of correcting fallacies about educational and psychological testing [Review of the book Correcting fallacies about educational and psychological testing , by R. P. Phelps, Eds.]. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 24 , 631–633.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Bowes, S. M. (in press). Intellectual humility: Ten unresolved questions. In P. Graf (Ed.), Current breakthroughs in applied psychology . Springer.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1 , 27–66.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Ammirati, R., & Landfield, K. (2009). Giving debiasing away: Can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4 , 390–398.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., Ruscio, J., & Beyerstein, B. L. (2010). 50 great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior. Wiley-Blackwell.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Ritschel, L. A., Lynn, S. J., Cautin, R. L., & Latzman, R. D. (2014). Why ineffective psychotherapies appear to work: A taxonomy of causes of spurious therapeutic effectiveness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9 , 355–387.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Smith, S. F., & Watts, A. L. (2016). The perils of unitary models of the etiology of mental disorders—The response modulation hypothesis of psychopathy as a case example: Rejoinder to Newman and Baskin-Sommers. Psychological Bulletin, 142 , 1394–1403.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., O’Donohue, W. T., & Latzman, R. D. (2017). Epistemic humility: An overarching educational philosophy for clinical psychology programs. Clinical Psychologist, 70 , 6–14.

MacLean, N., Neal, T., Morgan, R. D., & Murrie, D. C. (2019). Forensic clinicians’ understanding of bias. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 25 , 323–330.

McElroy, S. E., Rice, K. G., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., Hill, P. C., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2014). Intellectual humility: Scale development and theoretical elaborations in the context of religious leadership. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 42 , 19–30.

McElroy-Heltzel, S. E., Davis, D. E., DeBlaere, C., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Hook, J. N. (2019). Embarrassment of riches in the measurement of humility: A critical review of 22 measures. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14 , 393–404.

Meagher, B. R., Leman, J. C., Bias, J. P., Latendresse, S. J., & Rowatt, W. C. (2015). Contrasting self-report and consensus ratings of intellectual humility and arrogance. Journal of Research in Personality, 58 , 35–45.

Meagher, B. R., Leman, J. C., Heidenga, C. A., Ringquist, M. R., & Rowatt, W. C. (2021). Intellectual humility in conversation: Distinct behavioral indicators of self and peer ratings. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16 , 417–429.

Meichenbaum, D., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2018). How to spot hype in the field of psychotherapy: A 19-item checklist. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49 , 22–30.

Mendel, R., Traut-Mattausch, E., Jonas, E., Leucht, S., Kane, J. M., Maino, K., Kissling, W., & Hamann, J. (2011). Confirmation bias: Why psychiatrists stick to wrong preliminary diagnoses. Psychological Medicine, 41 , 2651–2659.

Nosek, B. A., Aarts, A. A., Anderson, J. E., Kappes, H. B., & Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349 .

O’Donohue, W. T., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Fowler, K. A. (2012). Science is an essential safeguard against human error. In The great ideas of clinical science (pp. 33–58). Routledge.

Porter, T., & Schumann, K. (2018). Intellectual humility and openness to the opposing view. Self and Identity, 17 , 139–162.

Porter, T., Schumann, K., Selmeczy, D., & Trzesniewski, K. (2020). Intellectual humility predicts mastery behaviors when learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 80 , 101888.

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y., & Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28 , 369–381.

Roberts, R. C., & Wood, W. J. (2018). Understanding, humility, and the vices of pride. In The Routledge handbook of virtue epistemology (pp. 363–376). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Rodriguez, C. G., Moskowitz, J. P., Salem, R. M., & Ditto, P. H. (2017). Partisan selective exposure: The role of party, ideology and ideological extremity over time. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 3 , 254–271.

Satel, S. L., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2013). Brainwashed: The seductive appeal of mindless neuroscience . Basic Books.

Senger, A. R., & Huynh, H. P. (2020). Intellectual humility’s association with vaccine attitudes and intentions. Psychology, Health & Medicine , 1–10.

Shrout, P. E., & Rodgers, J. L. (2018). Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: Broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annual Review of Psychology, 69 , 487–510.

Stanley, M. L., Sinclair, A. H., & Seli, P. (2020). Intellectual humility and perceptions of political opponents. Journal of Personality , 1–21.

Swift, V., & Peterson, J. B. (2019). Contextualization as a means to improve the predictive validity of personality models. Personality and Individual Differences, 144 , 153–163.

Tangney, J. P. (2000). Humility: Theoretical perspectives, empirical findings and directions for future research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19 , 70–82.

Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., Witvliet, & van Oyen, C. (2019). Humility. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28 , 463–468.

Whitcomb, D., Battaly, H., Baehr, J., & Howard-Snyder, D. (2017). Intellectual humility: Owning our limitations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 94 , 509–539.

Zachar, P. (2015). Popper, Meehl, and progress: The evolving concept of risky test in the science of psychopathology. Psychological Inquiry, 26 , 279–285.

Zhang, H., Hook, J. N., Farrell, J. E., Mosher, D. K., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Davis, D. E. (2018). The effect of religious diversity on religious belonging and meaning: The role of intellectual humility. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10 , 72–78.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Shauna M. Bowes & Adele Strother

Emory University School of Medicine, Druid Hills, GA, USA

Rachel J. Ammirati

Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Robert D. Latzman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Human Development and Family Science, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA

Cory L. Cobb

Department of Psychology, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY, USA

Steven Jay Lynn

Department of Psychology, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA

William O’Donohue

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Bowes, S.M., Strother, A., Ammirati, R.J., Latzman, R.D. (2022). Intellectual Humility: Definitions, Questions, and Scott O. Lilienfeld as a Case Example. In: Cobb, C.L., Lynn, S.J., O’Donohue, W. (eds) Toward a Science of Clinical Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14332-8_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14332-8_6

Published : 01 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-14331-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-14332-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Power of Intellectual Humility

What does it mean to be intellectually humble when it counts.

Posted April 13, 2022 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

I enjoy talking to strangers when I’m travelling. This might be because I’m a psychologist, or because I always try to look for the best in people, or perhaps it’s a reflection of the fact that a dear family friend christened me “Tigger” when I was a child because of my apparently rampant extraversion .

Regardless, whether it’s in a cab, on a plane, or at a party, I’m likely to be the one happily chatting away with people I’ve never met before and will perhaps never see again. I’ve received primers on the history of tobacco in North Carolina, been subjected to multiple attempts at conversion by practitioners of various religions, discussed the question of whether all languages are in fact governed by universal laws, and been complimented as apparently “one of the good ones” (I try not to overthink that one now).

I take particular joy when strangers ask me what I do for a living. I always give them the same answer: I study happiness . They usually find this hilarious and tell me either that it suits my personality (a compliment?) or ask me what the keys to happiness are (I usually go with having close relationships, or not sweating the small stuff).

However, if I’m being honest, I’m not telling them the whole truth about what I study, which is how we can live good lives. That is—how we can live lives of happiness, meaning, and purpose by successfully overcoming the challenges, failures, and adversity that are defining features of our lives, and how can we successfully develop into the best version of ourselves.

The good life is not simply about feeling happy, but also doing things of value, feeling some control over your life, and figuring out what’s true about our world. These days, I tend to think that perhaps the most important key to living well is the ability to see and understand both yourself and the world for what it really is. This means having: a) an accurate sense of oneself, and b) insight into what we can and cannot control.

This is much harder than you’d think. We as individuals routinely believe that we’re better than average on pretty much any conceivable trait or ability. Many of us who grew up in cultural settings that prioritize individual choice and action further believe that we are masters of our universe and that we can bend our environment to meet our desires. This belief typically decreases as we age and are subjected to multiple life lessons that teach us the importance of luck in our lives.

Seeing the world for what it really is is a form of wisdom . But it turns out that being wise is very hard. We each have our own biases (towards our own preferred in-groups, our families, our countries, our ideological commitments) that often shield us from the truth. Are there traits of character that we can develop to ensure that we understand the world the way it is?

I think intellectual humility may be one such trait. Being intellectually humble involves understanding your cognitive limitations—in simpler terms, it means acknowledging that you could be wrong about something. If you’re not open to acknowledging that you could be wrong, you can’t learn anything new about the world; you’re not going to be able to change your beliefs and grow.

As a human being, you probably intuit that this is a very hard thing to do.

It turns out that there is some evidence that backs up this intuition . In a study my colleagues and I at Wake Forest University conducted in 2017, we asked college students twice a day for three weeks if they had exhibited the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors characteristic of intellectual humility in an argument with someone over the previous twelve hours. The students then rated the extent to which they sought out reasons for why their current opinions could be wrong and used new information to reevaluate their existing beliefs. It turns out that they were more likely to manifest humility in situations where they saw the person they were arguing with as moral and therefore trustworthy.

Conversely, they were less likely to deploy humility in situations where they found the interaction to be disagreeable. Interestingly, the content of the disagreement— morality , facts, personal opinions—didn’t have an impact on the degree of intellectual humility. More important was what the speaker thought of their interlocutor.

What does it mean to be intellectually humble when it counts? I don’t know, to be honest (See what I did there?). But perhaps one way forward is to be mindful of how easily we can slip into defensiveness when we get into arguments, given that we all too easily see critiques of our understanding as critiques of our character. If we can remind ourselves of this tendency, perhaps we can find a way to remind ourselves that our interlocutors are not bad people, and that we can disagree without being disagreeable. This is a hard task, especially in the current political climate, as engaging with people we disagree with in this manner takes trust, curiosity, and open-mindedness.

I’ve learned a lot from my fellow passengers on my travels—not only new insights in areas outside my expertise, but also how other Americans outside a university setting understand and approach their world. These conversations have not always been easy, and I have confronted my limits at times. For example, while I think I generally handle comments that are arguably prejudiced with some degree of grace, I have recently found debating with anti-vaxxers to be an impossible task. Understanding the world involves understanding the perspectives that others bring to it, and this requires both patience and skill that can sometimes be difficult to muster.

One key challenge, I think, is remaining intellectually humble and open-minded as you grow older and develop (reasonably justifiable) beliefs about your own competence and abilities. For example, as a psychologist with what I believe to be a deep understanding of the research on well-being and personality, as well as a broader appreciation of the scientific method and scientific thinking, I unconsciously approach most conversations that touch on these topics with an “expert” mindset. However, Socrates taught us many years ago that “knowing oneself” involved interrogating one’s claims to knowledge, and that true knowledge may in fact involve a deep recognition of one’s ignorance.

In a way, gaining knowledge also involves dealing with the curse of knowledge—that complacent feeling that you’ve got it all figured out. In academia, I’ve found that increasing seniority is typically met with deference and occasionally (unwarranted) veneration. As the classicist Edith Hall noted in a 2019 talk, remaining critical of one’s own ideas and open-minded to others’ views in such a context takes some pretty significant—and constant—effort.

Both our psychology and our contexts make admitting what we don’t know very hard. We care about fitting in with family and friends, maintaining our ideological commitments, and feeling good about ourselves, all of which make facing up to the truth challenging. But I think we are also creatures that care about the truth. Caring about the truth involves being vulnerable about what we don’t know and inhabiting such a state can be unnerving. However, I think that taking such chances in our daily lives is key to achieving a rich and fulfilling life.

This essay is reprinted from the book Radical Humility , published by Belt Publishing, and edited by Rebekah Modrak and Jamie Vander Broek.

Eranda Jayawickreme, Ph.D. , is the Harold W. Tribble Professor of Psychology and Senior Research Fellow at the Program for Leadership and Character at Wake Forest University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Defining Critical Thinking

|

| ||

|

Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008)

Teacher’s College, Columbia University, 1941) | ||

| | ||

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 27 June 2022

Predictors and consequences of intellectual humility

- Tenelle Porter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4037-0412 1 ,

- Abdo Elnakouri 2 ,

- Ethan A. Meyers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6171-6780 2 ,

- Takuya Shibayama 2 ,

- Eranda Jayawickreme 3 &

- Igor Grossmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2681-3600 2

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 1 , pages 524–536 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

34k Accesses

52 Citations

523 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social behaviour

In a time of societal acrimony, psychological scientists have turned to a possible antidote — intellectual humility. Interest in intellectual humility comes from diverse research areas, including researchers studying leadership and organizational behaviour, personality science, positive psychology, judgement and decision-making, education, culture, and intergroup and interpersonal relationships. In this Review, we synthesize empirical approaches to the study of intellectual humility. We critically examine diverse approaches to defining and measuring intellectual humility and identify the common element: a meta-cognitive ability to recognize the limitations of one’s beliefs and knowledge. After reviewing the validity of different measurement approaches, we highlight factors that influence intellectual humility, from relationship security to social coordination. Furthermore, we review empirical evidence concerning the benefits and drawbacks of intellectual humility for personal decision-making, interpersonal relationships, scientific enterprise and society writ large. We conclude by outlining initial attempts to boost intellectual humility, foreshadowing possible scalable interventions that can turn intellectual humility into a core interpersonal, institutional and cultural value.

Similar content being viewed by others

In Japan, individuals of higher social class engage in other-oriented humor

Aspiring to greater intellectual humility in science.

Sordid genealogies: a conjectural history of Cambridge Analytica’s eugenic roots

Introduction.

Intellectual humility involves recognizing that there are gaps in one’s knowledge and that one’s current beliefs might be incorrect. For instance, someone might think that it is raining, but acknowledge that they have not looked outside to check and that the sun might be shining. Research on intellectual humility offers an intriguing avenue to safeguard against human errors and biases. Although it cannot eliminate them entirely, recognizing the limitations of knowledge might help to buffer people from some of their more authoritarian, dogmatic, and biased proclivities.

Although acknowledging the limits of one’s insights might be easy in low-stakes situations, people are less likely to exhibit intellectual humility when the stakes are high. For instance, people are unlikely to act in an intellectually humble manner when motivated by strong convictions or when their political, religious or ethical values seem to be challenged 1 , 2 . Under such circumstances, many people hold tightly to existing beliefs and fail to appreciate and acknowledge the viewpoints of others 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . These social phenomena have troubled scholars and policymakers for decades 3 . Consequently, interest in cultivating intellectual humility has come from multiple research areas and subfields in psychology, including social-personality, cognitive, clinical, educational, and leadership and organizational behaviour 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . Cumulatively, research suggests that intellectual humility can decrease polarization, extremism and susceptibility to conspiracy beliefs, increase learning and discovery, and foster scientific credibility 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 .

The growing interdisciplinary interest in intellectual humility has led to multiple definitions and assessments, raising a question about commonality across definitions of the concept. Claims about its presumed societal and individual benefits further raise questions about the strength of evidence that supports these claims.

In this Review, we provide an overview of empirical intellectual humility research. We first examine approaches for defining and measuring intellectual humility across various subfields in psychology, synthesizing the common thread across seemingly disparate definitions. We next describe how individual, interpersonal and cultural factors can work for or against intellectual humility. We conclude by highlighting the importance of intellectual humility and detailing interventions to increase its prevalence.

Defining intellectual humility

Intellectual humility is conceptually distinct from general humility, modesty, perspective-taking and open-mindedness 9 . Whereas general humility involves how people think about their shortcomings and strengths across domains, intellectual humility is chiefly concerned with epistemic limitations 16 . In a similar vein, modesty emphasizes increased social awareness and not wanting to monopolize the spotlight or draw too much attention to one’s accomplishments, whereas intellectual humility focuses on recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility 17 . General humility and modesty are also psychometrically distinct from intellectual humility 18 , 19 .

There are subtle differences between intellectual humility and perspective-taking. Perspective-taking is the ability to recognize and understand alternative points of view 20 . By contrast, intellectual humility is the ability to recognize shortcomings or potential limitations in one’s own point of view. Building on perspective-taking, open-mindedness refers to unbiased or fair consideration of different views regardless of one’s beliefs 21 . Although open-mindedness is theoretically and empirically related to intellectual humility, being open-minded does not always involve considering the limitations of one’s knowledge or beliefs 22 , 23 . Although it is distinct from these related phenomena, intellectual humility has multiple definitions, reflecting its use in different fields.

Intellectual humility has a wide range of philosophical roots 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 . Some philosophical accounts focus on attributes of people who frequently exhibit intellectually humble thoughts and behaviour (such as the tendency to recognize one’s fallibility and own one’s limitations) 28 . Most accounts define intellectual humility as a virtuous balance between intellectual arrogance (overvaluing one’s beliefs) and intellectual diffidence (undervaluing one’s beliefs) 28 , 29 , 30 . This definition has its roots in the Aristotelian ideal of the Golden Mean — a calibration of particular virtues to the demands of the situation at hand 30 , 31 . Because situations vary in their demands, a logical consequence of the Aristotelian approach is that intellectual humility is virtuous only as a dynamic, situation-sensitive construct 30 , 31 , 32 . Simultaneously, the Aristotelian approach means that the same psychological characteristics attributed to intellectual humility are unlikely to always be virtuous 32 .

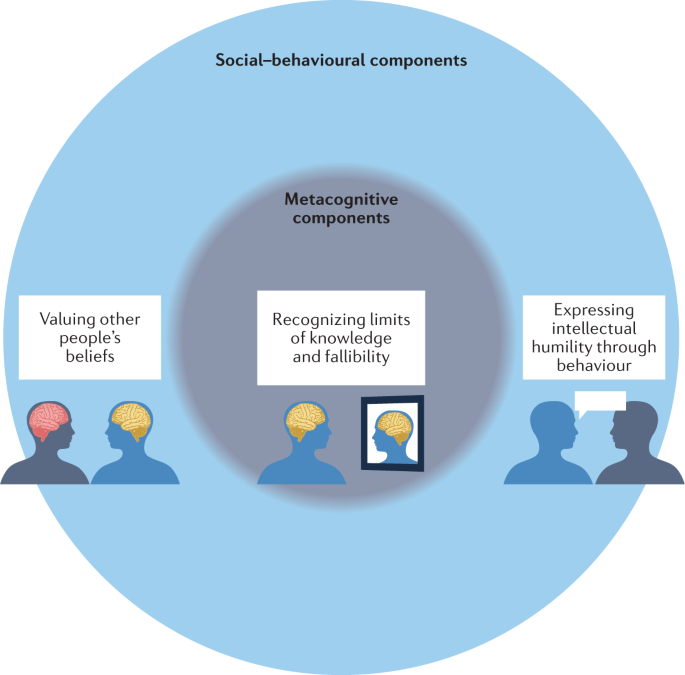

Psychological scientists also define intellectual humility in a myriad of ways. Some scholars approach intellectual humility as a form of metacognition, reflecting how people regulate and reflect on their beliefs and thoughts. This view emphasizes the inherent limitations of human knowledge and beliefs, such as recognizing that beliefs might be wrong and that opinions are based on partial information 9 , 29 , 33 , 34 . Other scholars approach intellectual humility as a multidimensional phenomenon, advocating that intellectual humility includes a combination of metacognition, valuing other people’s beliefs, admitting one’s ignorance or errors to other people, and being motivated by an intrinsic desire to seek the truth 35 , 36 , 37 .

Scholars favouring broader accounts of intellectual humility argue that a strict focus on metacognition excludes appreciation for other people’s insights, behavioural responses when one recognizes that they might be wrong or confused, and motives for thinking and acting. In turn, scholars who endorse a metacognitive account of intellectual humility argue that encumbering intellectual humility with multiple features weakens the ability to examine it with conceptual clarity and methodological rigour. For example, multidimensional instruments might be difficult to interpret because a person high in one dimension and low in another could receive the same intellectual humility score as someone with the opposite psychological profile.

Preference for these competing accounts of intellectual humility varies across subfields of psychology, linked to methodological preferences and historical emphasis on social and contextual factors. Cognitive psychologists tend to favour metacognitive accounts that emphasize how people think about evidence, knowledge and beliefs, without much attention to social contexts 13 . Conversely, developmental, educational and clinical psychologists tend to favour a multidimensional account that considers how real world, cognitive, behavioural and interpersonal factors come together to form intellectual humility 38 , 39 , 40 . Social and personality psychologists, including those in the applied organizational sciences, consider metacognitive and multidimensional accounts 9 , 33 . Rather than endorsing a single definition, these researchers call for a clear distinction when measuring unique features of intellectual humility to reveal how the distinctive features relate to and shape one another 41 .

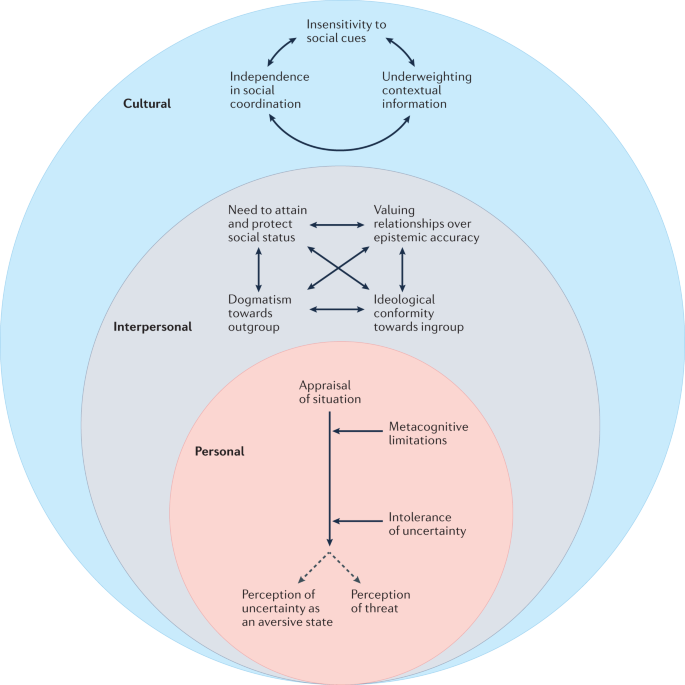

A cumulative science of intellectual humility benefits from clear definitions and explicit modelling of relationships between psychological processes and behavioural outcomes. Despite different conceptual approaches, most philosophers and psychologists agree that intellectual humility necessarily includes recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility 26 . Hence, we focus on the metacognitive features of intellectual humility because they have consensus support from the scholarly community. Furthermore, these features are empirically plausible: they are scientifically testable and hence falsifiable. Taking a middle ground between metacognitive and multidimensional accounts, we argue that consideration of interpersonal contexts is beneficial for understanding how intellectual humility manifests, what factors inhibit and promote it, and how intellectual humility can be developed. At the same time, isolating the metacognitive core of intellectual humility permits scholars to identify its contextual and interpersonal correlates and reduces the likelihood of mistakenly labelling distinct processes and outcomes as intellectual humility (the jingle fallacy) or providing distinct names to the same family of metacognitive components of intellectual humility (the jangle fallacy) 41 . Thus, we define intellectual humility in terms of a metacognitive core composed of recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge and awareness of one’s fallibility (Fig. 1 ). This core is expressed by demonstrations of intellectual humility through behaviour and valuing the intellect of others.

The core metacognitive components of intellectual humility (grey) include recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge and being aware of one’s fallibility. The peripheral social and behavioural features of intellectual humility (light blue) include recognizing that other people can hold legitimate beliefs different from one’s own and a willingness to reveal ignorance and confusion in order to learn. The boundaries of the core and peripheral region are permeable, indicating the mutual influence of metacognitive features of intellectual humility for social and behavioural aspects of the construct and vice versa.

Measuring intellectual humility

Psychological scientists have developed several measures of intellectual humility (Table 1 ). These measures can be organized in terms of the aspect of intellectual humility they target and the type of measure. In terms of aspect, some measures aim to capture intellectual humility as a trait — the degree to which people are intellectually humble in general — whereas others examine it as a state — the degree to which people are intellectually humble in specific contexts. In both cases, intellectual humility is measured along a continuum rather than as a binary measure.

One type of measurement is to ask participants to self-report on their intellectual humility in a questionnaire 26 . Questionnaires are used to assess trait and state (including belief-specific) intellectual humility. Another measurement type relies on behavioural tasks designed to elicit meaningful differences in a particular kind of response. For example, a researcher might ask people to play a game where the goal is to answer questions correctly and see how often participants delegate questions to more knowledgeable peers — an indication that people realize their own knowledge is incomplete (this task has been used to measure intellectual humility in children 38 ). Both of these measurement types can contribute to estimates of trait and state intellectual humility.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are often used to assess intellectual humility. A trait questionnaire might ask how much a person “[accepts] that [their] beliefs and attitudes may be wrong” 9 . A belief-specific questionnaire on the issue of gun control might ask how much a person “[recognizes] that [their] views about gun control are based on limited evidence” 33 . A state questionnaire might ask how intellectually humble a person feels in the moment or how much they “searched actively for reasons why [their] beliefs might be wrong” during a recent disagreement or conflict 37 . A closely related self-report measure asks people to indicate, for example, their attitude change or depth of understanding. These self-report tasks have been used as indirect measures of intellectual humility 42 .

Over the last decade, psychological scientists have developed many questionnaire measures of intellectual humility at the trait level 26 . The popularity of these measures is due to some level of predictive capacity and cost-effectiveness. People seem to be capable of reporting on their trait level of intellectual humility with some degree of accuracy, as supported by small-to-moderate positive correlations between self-reported intellectual humility and peer-reported intellectual humility 9 , 11 , 19 , 43 . Scores on self-reported trait-level intellectual humility (across different measures) are also positively associated with scores on self-report measures of other epistemic traits, such as intellect and open-mindedness, and to behaviours understood to be central to intellectual humility (including information-seeking, cognitive flexibility, acknowledgement of intellectual failings and argument evaluation) 9 , 11 , 19 , 43 , 44 .

Nevertheless, trait-level questionnaires of intellectual humility have limitations. All questionnaires rely on subjective judgements and are therefore vulnerable to response biases. Relevant biases include not accurately recalling one’s past experience, selecting positive responses on the measure by default, seeing oneself more positively than is warranted and focusing on favourable group comparisons when evaluating one’s behaviour. Thus, self-reports of one’s general intellectual humility provides numerous opportunities for error 45 , 46 .

Finally, it is difficult to assess socially desirable constructs with self-report measures. Scores obtained via trait-style measures of intellectual humility positively correlate with social desirability bias. In situations where intellectual humility is desirable, such as a job interview, self-report questionnaires make it easy to create a false impression of high intellectual humility 47 , 48 . Notably, response biases are attenuated when intellectual humility questionnaires ask people to report how intellectually humble they were in specific interpersonal situations in their lives, highlighting the value of more contextualized assessment of responses to specific situations (or states) 49 . In particular, reporting on how one searched for information or whether one recognized one’s fallibility during a specific event does not require as much mental effort because of access to specific memory cues, compared to reporting on how intellectually humble one is across many situations. In addition, when recalling a specific situation, a desire to present oneself in a positive light might be trumped by a stronger desire to provide an honest response about a particular event. Thus, questionnaires that ask about intellectual humility in specific situations or relevant to specific events might be less vulnerable to response bias than questionnaires that measure trait-level intellectual humility.

In sum, trait-level questionnaires might seem to be an efficient tool for obtaining an initial, general picture about one’s intellectual humility. However, these scores should be considered in light of their limitations. Although trait measures can be useful for describing typical ways of being in the world, they are not particularly good at detecting variability. Thus, they are not well suited to studying how intellectual humility might vary in daily life or change in response to an intervention. In response to these limitations, some researchers have examined intellectual humility in specific contexts or in response to specific issues. Scholars studying these questions have developed state-specific questionnaires about one’s beliefs, reasoning or behaviour that tap into intellectual humility about specific issues, such as gun control, vaccine mandates or more mundane interpersonal disagreements 37 , 49 , 50 . State measures enable researchers to capture how people’s intellectual humility varies as they move through various contexts and situations 37 , 50 , 51 .

Although individuals differ in their trait-level intellectual humility, they can also demonstrate a high degree of systematic variation depending on the demands of specific contexts. Capturing only global self-perceptions of intellectual humility with a trait measure glosses over this variability and nuance. By contrast, focus on state-specific measures echoes modern personality science, which defines a trait via a person’s profile of states 52 , 53 . A person’s profile — when aggregating across state-specific expressions of a characteristic — is typically stable over time. At the same time, state-specific expression of a characteristic will systematically vary across situations. Indeed, daily diary and experience-sampling studies demonstrate substantial within-person variability in intellectual humility 37 , 50 .

When researchers are interested in people’s overall patterns of intellectual humility across situations and variability from situation to situation, we recommend integrating state and trait approaches by taking repeated situation-specific assessments. We recommend reports of intellectual humility in the context of specific situations. Ideally, these assessments should be administered multiple times. We suggest using trait-level assessments of intellectual humility only for research focused on people’s global attributions of intellectual humility to themselves (self-reports) or close others (informant reports). A profile of intellectual humility can be further established by modelling responses across multiple situations.

If researchers are solely interested in participants’ general self-perceptions of intellectual humility, trait assessments might be suitable, with the caveats outlined above. Notably, little work has directly compared benefits of trait assessments of intellectual humility to repeated situation-specific assessments of intellectual humility, and further research on this topic is needed.

Behavioural tasks

A key advantage of behavioural tasks over other measures is that their scores do not typically depend on subjective judgements and therefore are not as prone to response biases and faking 45 , 47 , 48 . For example, measuring whether a person delegates a question to a more knowledgeable peer captures a real behaviour in the moment, in contrast to a self-report of a person’s impression of their behaviour in general or in a past situation. In addition, behavioural tasks depend less on language than questionnaires and might therefore be better for assessing intellectual humility in young children or in different cultural contexts. Behavioural tasks also put all participants in the same situation with the same opportunity to exhibit intellectual humility. By comparison, estimates of intellectual humility via questionnaires suffer from the confound of natural variability in the opportunity to be intellectually humble in daily life.

Nonetheless, custom-designed behavioural tasks can be less effective at measuring typical rather than extraordinary performance 54 . Experimental tasks capture only a small segment of behaviour in an artificial situation contrived by a researcher. A participant might be highly motivated to perform well on the task by displaying high levels of intellectual humility, rendering a score that captures their maximal capacity rather than their typical or externally valid intellectual humility. Behavioural measures also assume that the assessed behaviour is motivated by recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility, which might not always be the case. Such behaviour might be motivated by situational pressures or other processes not characteristic of intellectual humility.