Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

- Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed numerically. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

- Qualitative research gathers non-numerical data (words, images, sounds) to explore subjective experiences and attitudes, often via observation and interviews. It aims to produce detailed descriptions and uncover new insights about the studied phenomenon.

On This Page:

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography .

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

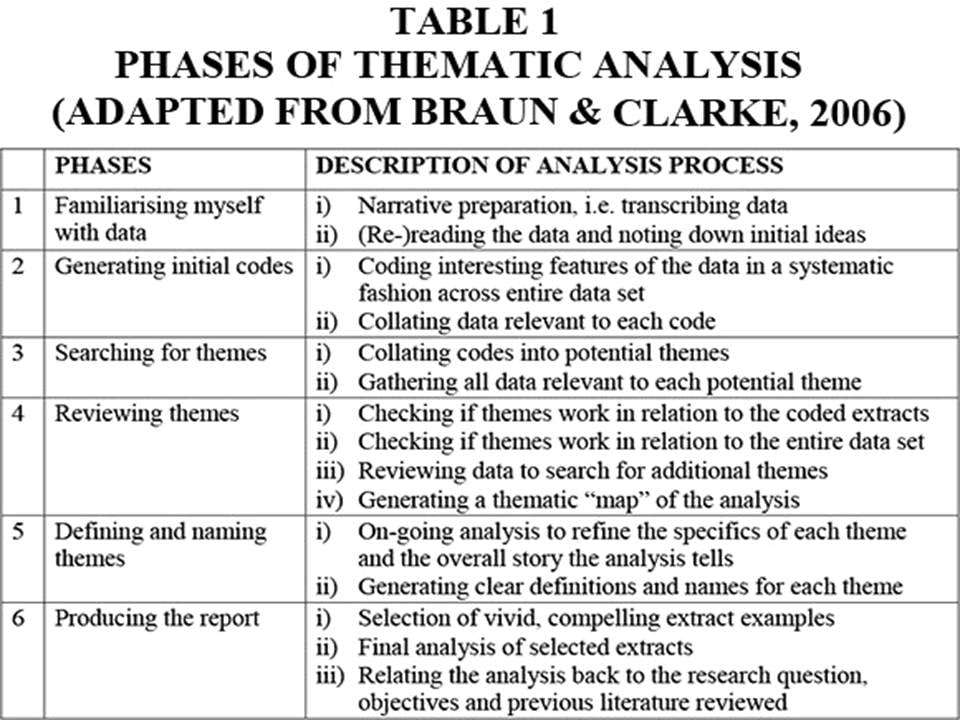

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis .

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded .

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

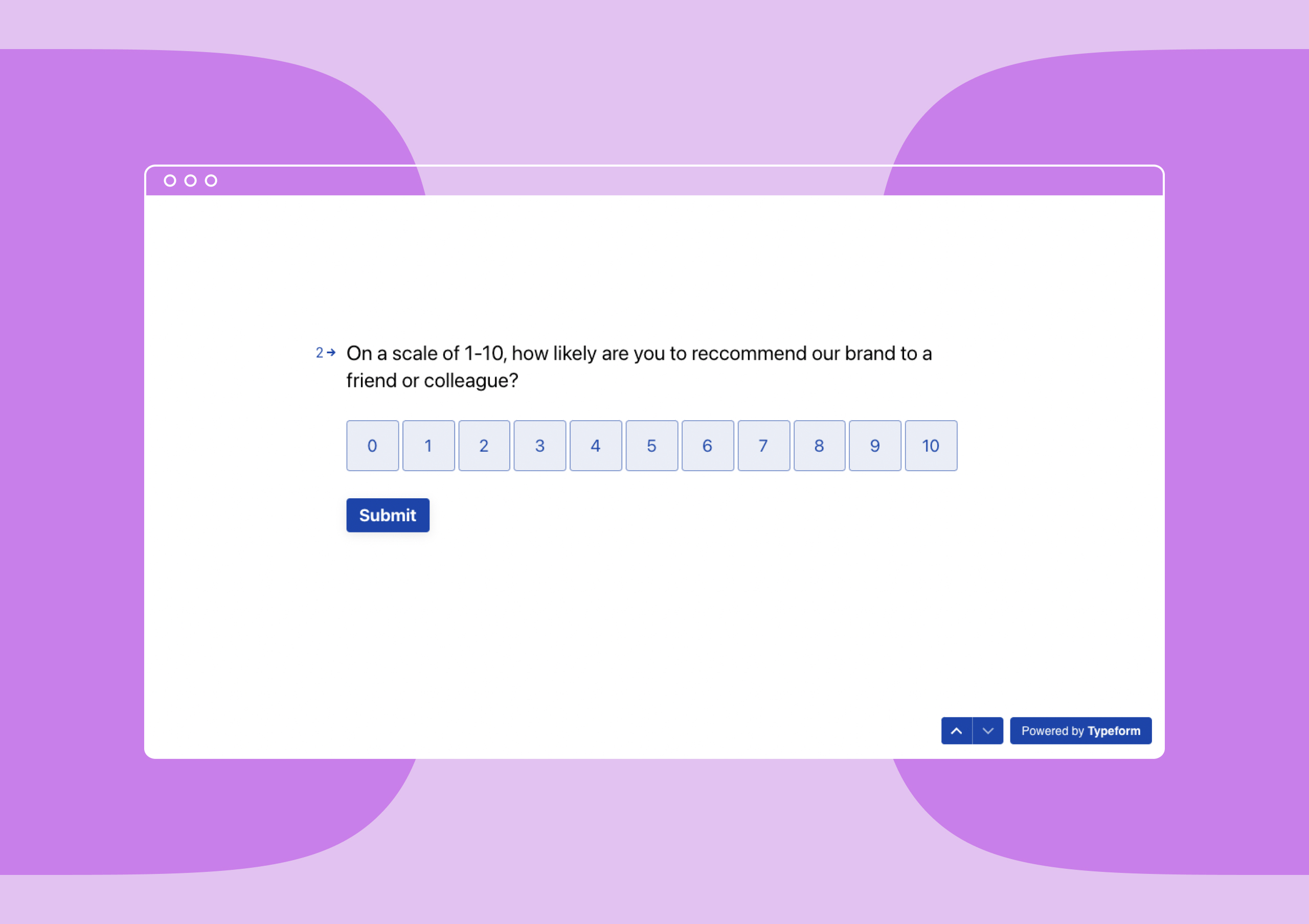

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Mixed methods research

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

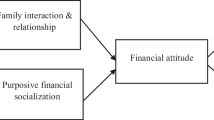

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

| Quantitative research questions | Quantitative research hypotheses |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research questions | Simple hypothesis |

| Comparative research questions | Complex hypothesis |

| Relationship research questions | Directional hypothesis |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| Hypothesis-testing | |

| Qualitative research questions | Qualitative research hypotheses |

| Contextual research questions | Hypothesis-generating |

| Descriptive research questions | |

| Evaluation research questions | |

| Explanatory research questions | |

| Exploratory research questions | |

| Generative research questions | |

| Ideological research questions | |

| Ethnographic research questions | |

| Phenomenological research questions | |

| Grounded theory questions | |

| Qualitative case study questions |

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

| Quantitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Measures responses of subjects to variables | |

| - Presents variables to measure, analyze, or assess | |

| What is the proportion of resident doctors in the hospital who have mastered ultrasonography (response of subjects to a variable) as a diagnostic technique in their clinical training? | |

| Comparative research question | |

| - Clarifies difference between one group with outcome variable and another group without outcome variable | |

| Is there a difference in the reduction of lung metastasis in osteosarcoma patients who received the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group with outcome variable) compared with osteosarcoma patients who did not receive the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group without outcome variable)? | |

| - Compares the effects of variables | |

| How does the vitamin D analogue 22-Oxacalcitriol (variable 1) mimic the antiproliferative activity of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (variable 2) in osteosarcoma cells? | |

| Relationship research question | |

| - Defines trends, association, relationships, or interactions between dependent variable and independent variable | |

| Is there a relationship between the number of medical student suicide (dependent variable) and the level of medical student stress (independent variable) in Japan during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

| Quantitative research hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Simple hypothesis | |

| - Predicts relationship between single dependent variable and single independent variable | |

| If the dose of the new medication (single independent variable) is high, blood pressure (single dependent variable) is lowered. | |

| Complex hypothesis | |

| - Foretells relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables | |

| The higher the use of anticancer drugs, radiation therapy, and adjunctive agents (3 independent variables), the higher would be the survival rate (1 dependent variable). | |

| Directional hypothesis | |

| - Identifies study direction based on theory towards particular outcome to clarify relationship between variables | |

| Privately funded research projects will have a larger international scope (study direction) than publicly funded research projects. | |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| - Nature of relationship between two variables or exact study direction is not identified | |

| - Does not involve a theory | |

| Women and men are different in terms of helpfulness. (Exact study direction is not identified) | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| - Describes variable interdependency | |

| - Change in one variable causes change in another variable | |

| A larger number of people vaccinated against COVID-19 in the region (change in independent variable) will reduce the region’s incidence of COVID-19 infection (change in dependent variable). | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| - An effect on dependent variable is predicted from manipulation of independent variable | |

| A change into a high-fiber diet (independent variable) will reduce the blood sugar level (dependent variable) of the patient. | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| - A negative statement indicating no relationship or difference between 2 variables | |

| There is no significant difference in the severity of pulmonary metastases between the new drug (variable 1) and the current drug (variable 2). | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| - Following a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis predicts a relationship between 2 study variables | |

| The new drug (variable 1) is better on average in reducing the level of pain from pulmonary metastasis than the current drug (variable 2). | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory | |

| Dairy cows fed with concentrates of different formulations will produce different amounts of milk. | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| - Assumption about the value of population parameter or relationship among several population characteristics | |

| - Validity tested by a statistical experiment or analysis | |

| The mean recovery rate from COVID-19 infection (value of population parameter) is not significantly different between population 1 and population 2. | |

| There is a positive correlation between the level of stress at the workplace and the number of suicides (population characteristics) among working people in Japan. | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| - Offers or proposes an explanation with limited or no extensive evidence | |

| If healthcare workers provide more educational programs about contraception methods, the number of adolescent pregnancies will be less. | |

| Hypothesis-testing (Quantitative hypothesis-testing research) | |

| - Quantitative research uses deductive reasoning. | |

| - This involves the formation of a hypothesis, collection of data in the investigation of the problem, analysis and use of the data from the investigation, and drawing of conclusions to validate or nullify the hypotheses. | |

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

| Qualitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Contextual research question | |

| - Ask the nature of what already exists | |

| - Individuals or groups function to further clarify and understand the natural context of real-world problems | |

| What are the experiences of nurses working night shifts in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic? (natural context of real-world problems) | |

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Aims to describe a phenomenon | |

| What are the different forms of disrespect and abuse (phenomenon) experienced by Tanzanian women when giving birth in healthcare facilities? | |

| Evaluation research question | |

| - Examines the effectiveness of existing practice or accepted frameworks | |

| How effective are decision aids (effectiveness of existing practice) in helping decide whether to give birth at home or in a healthcare facility? | |

| Explanatory research question | |

| - Clarifies a previously studied phenomenon and explains why it occurs | |

| Why is there an increase in teenage pregnancy (phenomenon) in Tanzania? | |

| Exploratory research question | |

| - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated to have a deeper understanding of the research problem | |

| What factors affect the mental health of medical students (areas that have not yet been fully investigated) during the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

| Generative research question | |

| - Develops an in-depth understanding of people’s behavior by asking ‘how would’ or ‘what if’ to identify problems and find solutions | |

| How would the extensive research experience of the behavior of new staff impact the success of the novel drug initiative? | |

| Ideological research question | |

| - Aims to advance specific ideas or ideologies of a position | |

| Are Japanese nurses who volunteer in remote African hospitals able to promote humanized care of patients (specific ideas or ideologies) in the areas of safe patient environment, respect of patient privacy, and provision of accurate information related to health and care? | |

| Ethnographic research question | |

| - Clarifies peoples’ nature, activities, their interactions, and the outcomes of their actions in specific settings | |

| What are the demographic characteristics, rehabilitative treatments, community interactions, and disease outcomes (nature, activities, their interactions, and the outcomes) of people in China who are suffering from pneumoconiosis? | |

| Phenomenological research question | |

| - Knows more about the phenomena that have impacted an individual | |

| What are the lived experiences of parents who have been living with and caring for children with a diagnosis of autism? (phenomena that have impacted an individual) | |

| Grounded theory question | |

| - Focuses on social processes asking about what happens and how people interact, or uncovering social relationships and behaviors of groups | |

| What are the problems that pregnant adolescents face in terms of social and cultural norms (social processes), and how can these be addressed? | |

| Qualitative case study question | |

| - Assesses a phenomenon using different sources of data to answer “why” and “how” questions | |

| - Considers how the phenomenon is influenced by its contextual situation. | |

| How does quitting work and assuming the role of a full-time mother (phenomenon assessed) change the lives of women in Japan? | |

| Qualitative research hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis-generating (Qualitative hypothesis-generating research) | |

| - Qualitative research uses inductive reasoning. | |

| - This involves data collection from study participants or the literature regarding a phenomenon of interest, using the collected data to develop a formal hypothesis, and using the formal hypothesis as a framework for testing the hypothesis. | |

| - Qualitative exploratory studies explore areas deeper, clarifying subjective experience and allowing formulation of a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach. | |

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

| Variables | Unclear and weak statement (Statement 1) | Clear and good statement (Statement 2) | Points to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research question | Which is more effective between smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion? | “Moreover, regarding smoke moxibustion versus smokeless moxibustion, it remains unclear which is more effective, safe, and acceptable to pregnant women, and whether there is any difference in the amount of heat generated.” | 1) Vague and unfocused questions |

| 2) Closed questions simply answerable by yes or no | |||

| 3) Questions requiring a simple choice | |||

| Hypothesis | The smoke moxibustion group will have higher cephalic presentation. | “Hypothesis 1. The smoke moxibustion stick group (SM group) and smokeless moxibustion stick group (-SLM group) will have higher rates of cephalic presentation after treatment than the control group. | 1) Unverifiable hypotheses |

| Hypothesis 2. The SM group and SLM group will have higher rates of cephalic presentation at birth than the control group. | 2) Incompletely stated groups of comparison | ||

| Hypothesis 3. There will be no significant differences in the well-being of the mother and child among the three groups in terms of the following outcomes: premature birth, premature rupture of membranes (PROM) at < 37 weeks, Apgar score < 7 at 5 min, umbilical cord blood pH < 7.1, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and intrauterine fetal death.” | 3) Insufficiently described variables or outcomes | ||

| Research objective | To determine which is more effective between smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion. | “The specific aims of this pilot study were (a) to compare the effects of smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion treatments with the control group as a possible supplement to ECV for converting breech presentation to cephalic presentation and increasing adherence to the newly obtained cephalic position, and (b) to assess the effects of these treatments on the well-being of the mother and child.” | 1) Poor understanding of the research question and hypotheses |

| 2) Insufficient description of population, variables, or study outcomes |

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

| Variables | Unclear and weak statement (Statement 1) | Clear and good statement (Statement 2) | Points to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research question | Does disrespect and abuse (D&A) occur in childbirth in Tanzania? | How does disrespect and abuse (D&A) occur and what are the types of physical and psychological abuses observed in midwives’ actual care during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania? | 1) Ambiguous or oversimplistic questions |

| 2) Questions unverifiable by data collection and analysis | |||

| Hypothesis | Disrespect and abuse (D&A) occur in childbirth in Tanzania. | Hypothesis 1: Several types of physical and psychological abuse by midwives in actual care occur during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. | 1) Statements simply expressing facts |

| Hypothesis 2: Weak nursing and midwifery management contribute to the D&A of women during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. | 2) Insufficiently described concepts or variables | ||

| Research objective | To describe disrespect and abuse (D&A) in childbirth in Tanzania. | “This study aimed to describe from actual observations the respectful and disrespectful care received by women from midwives during their labor period in two hospitals in urban Tanzania.” | 1) Statements unrelated to the research question and hypotheses |

| 2) Unattainable or unexplorable objectives |

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

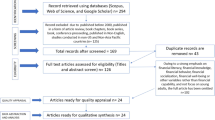

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research in Psychology

- Key Differences

Quantitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods.

- How They Relate

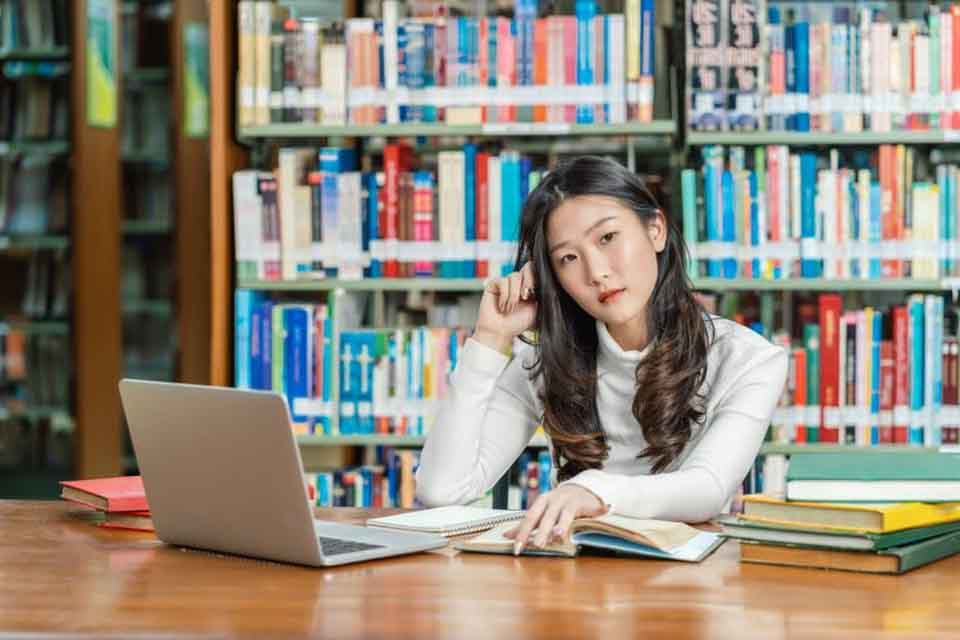

In psychology and other social sciences, researchers are faced with an unresolved question: Can we measure concepts like love or racism the same way we can measure temperature or the weight of a star? Social phenomena—things that happen because of and through human behavior—are especially difficult to grasp with typical scientific models.

At a Glance

Psychologists rely on quantitative and quantitative research to better understand human thought and behavior.

- Qualitative research involves collecting and evaluating non-numerical data in order to understand concepts or subjective opinions.

- Quantitative research involves collecting and evaluating numerical data.

This article discusses what qualitative and quantitative research are, how they are different, and how they are used in psychology research.

Qualitative Research vs. Quantitative Research

In order to understand qualitative and quantitative psychology research, it can be helpful to look at the methods that are used and when each type is most appropriate.

Psychologists rely on a few methods to measure behavior, attitudes, and feelings. These include:

- Self-reports , like surveys or questionnaires

- Observation (often used in experiments or fieldwork)

- Implicit attitude tests that measure timing in responding to prompts

Most of these are quantitative methods. The result is a number that can be used to assess differences between groups.

However, most of these methods are static, inflexible (you can't change a question because a participant doesn't understand it), and provide a "what" answer rather than a "why" answer.

Sometimes, researchers are more interested in the "why" and the "how." That's where qualitative methods come in.

Qualitative research is about speaking to people directly and hearing their words. It is grounded in the philosophy that the social world is ultimately unmeasurable, that no measure is truly ever "objective," and that how humans make meaning is just as important as how much they score on a standardized test.

Used to develop theories

Takes a broad, complex approach

Answers "why" and "how" questions

Explores patterns and themes

Used to test theories

Takes a narrow, specific approach

Answers "what" questions

Explores statistical relationships

Quantitative methods have existed ever since people have been able to count things. But it is only with the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte (which maintains that factual knowledge obtained by observation is trustworthy) that it became a "scientific method."

The scientific method follows this general process. A researcher must:

- Generate a theory or hypothesis (i.e., predict what might happen in an experiment) and determine the variables needed to answer their question

- Develop instruments to measure the phenomenon (such as a survey, a thermometer, etc.)

- Develop experiments to manipulate the variables

- Collect empirical (measured) data

- Analyze data

Quantitative methods are about measuring phenomena, not explaining them.

Quantitative research compares two groups of people. There are all sorts of variables you could measure, and many kinds of experiments to run using quantitative methods.

These comparisons are generally explained using graphs, pie charts, and other visual representations that give the researcher a sense of how the various data points relate to one another.

Basic Assumptions

Quantitative methods assume:

- That the world is measurable

- That humans can observe objectively

- That we can know things for certain about the world from observation

In some fields, these assumptions hold true. Whether you measure the size of the sun 2000 years ago or now, it will always be the same. But when it comes to human behavior, it is not so simple.

As decades of cultural and social research have shown, people behave differently (and even think differently) based on historical context, cultural context, social context, and even identity-based contexts like gender , social class, or sexual orientation .

Therefore, quantitative methods applied to human behavior (as used in psychology and some areas of sociology) should always be rooted in their particular context. In other words: there are no, or very few, human universals.

Statistical information is the primary form of quantitative data used in human and social quantitative research. Statistics provide lots of information about tendencies across large groups of people, but they can never describe every case or every experience. In other words, there are always outliers.

Correlation and Causation

A basic principle of statistics is that correlation is not causation. Researchers can only claim a cause-and-effect relationship under certain conditions:

- The study was a true experiment.

- The independent variable can be manipulated (for example, researchers cannot manipulate gender, but they can change the primer a study subject sees, such as a picture of nature or of a building).

- The dependent variable can be measured through a ratio or a scale.

So when you read a report that "gender was linked to" something (like a behavior or an attitude), remember that gender is NOT a cause of the behavior or attitude. There is an apparent relationship, but the true cause of the difference is hidden.

Pitfalls of Quantitative Research

Quantitative methods are one way to approach the measurement and understanding of human and social phenomena. But what's missing from this picture?

As noted above, statistics do not tell us about personal, individual experiences and meanings. While surveys can give a general idea, respondents have to choose between only a few responses. This can make it difficult to understand the subtleties of different experiences.

Quantitative methods can be helpful when making objective comparisons between groups or when looking for relationships between variables. They can be analyzed statistically, which can be helpful when looking for patterns and relationships.

Qualitative data are not made out of numbers but rather of descriptions, metaphors, symbols, quotes, analysis, concepts, and characteristics. This approach uses interviews, written texts, art, photos, and other materials to make sense of human experiences and to understand what these experiences mean to people.

While quantitative methods ask "what" and "how much," qualitative methods ask "why" and "how."

Qualitative methods are about describing and analyzing phenomena from a human perspective. There are many different philosophical views on qualitative methods, but in general, they agree that some questions are too complex or impossible to answer with standardized instruments.

These methods also accept that it is impossible to be completely objective in observing phenomena. Researchers have their own thoughts, attitudes, experiences, and beliefs, and these always color how people interpret results.

Qualitative Approaches

There are many different approaches to qualitative research, with their own philosophical bases. Different approaches are best for different kinds of projects. For example:

- Case studies and narrative studies are best for single individuals. These involve studying every aspect of a person's life in great depth.

- Phenomenology aims to explain experiences. This type of work aims to describe and explore different events as they are consciously and subjectively experienced.

- Grounded theory develops models and describes processes. This approach allows researchers to construct a theory based on data that is collected, analyzed, and compared to reach new discoveries.

- Ethnography describes cultural groups. In this approach, researchers immerse themselves in a community or group in order to observe behavior.

Qualitative researchers must be aware of several different methods and know each thoroughly enough to produce valuable research.

Some researchers specialize in a single method, but others specialize in a topic or content area and use many different methods to explore the topic, providing different information and a variety of points of view.

There is not a single model or method that can be used for every qualitative project. Depending on the research question, the people participating, and the kind of information they want to produce, researchers will choose the appropriate approach.

Interpretation

Qualitative research does not look into causal relationships between variables, but rather into themes, values, interpretations, and meanings. As a rule, then, qualitative research is not generalizable (cannot be applied to people outside the research participants).

The insights gained from qualitative research can extend to other groups with proper attention to specific historical and social contexts.

Relationship Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

It might sound like quantitative and qualitative research do not play well together. They have different philosophies, different data, and different outputs. However, this could not be further from the truth.

These two general methods complement each other. By using both, researchers can gain a fuller, more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

For example, a psychologist wanting to develop a new survey instrument about sexuality might and ask a few dozen people questions about their sexual experiences (this is qualitative research). This gives the researcher some information to begin developing questions for their survey (which is a quantitative method).

After the survey, the same or other researchers might want to dig deeper into issues brought up by its data. Follow-up questions like "how does it feel when...?" or "what does this mean to you?" or "how did you experience this?" can only be answered by qualitative research.

By using both quantitative and qualitative data, researchers have a more holistic, well-rounded understanding of a particular topic or phenomenon.

Qualitative and quantitative methods both play an important role in psychology. Where quantitative methods can help answer questions about what is happening in a group and to what degree, qualitative methods can dig deeper into the reasons behind why it is happening. By using both strategies, psychology researchers can learn more about human thought and behavior.

Gough B, Madill A. Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect . Psychol Methods . 2012;17(3):374-384. doi:10.1037/a0029313

Pearce T. “Science organized”: Positivism and the metaphysical club, 1865–1875 . J Hist Ideas . 2015;76(3):441-465.

Adams G. Context in person, person in context: A cultural psychology approach to social-personality psychology . In: Deaux K, Snyder M, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology . Oxford University Press; 2012:182-208.

Brady HE. Causation and explanation in social science . In: Goodin RE, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press; 2011. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0049

Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers . SAGE Open Med . 2019;7:2050312118822927. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927

Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80 . Medical Teacher . 2013;35(8):e1365-e1379. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

Salkind NJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Research Design . Sage Publishing.

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research Methods in Psychology . McGraw Hill Education.

By Anabelle Bernard Fournier Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: Differences, Examples, and Methods

There are two broad kinds of research approaches: qualitative and quantitative research that are used to study and analyze phenomena in various fields such as natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. Whether you have realized it or not, your research must have followed either or both research types. In this article we will discuss what qualitative vs quantitative research is, their applications, pros and cons, and when to use qualitative vs quantitative research . Before we get into the details, it is important to understand the differences between the qualitative and quantitative research.

Table of Contents

Qualitative v s Quantitative Research

Quantitative research deals with quantity, hence, this research type is concerned with numbers and statistics to prove or disapprove theories or hypothesis. In contrast, qualitative research is all about quality – characteristics, unquantifiable features, and meanings to seek deeper understanding of behavior and phenomenon. These two methodologies serve complementary roles in the research process, each offering unique insights and methods suited to different research questions and objectives.

Qualitative and quantitative research approaches have their own unique characteristics, drawbacks, advantages, and uses. Where quantitative research is mostly employed to validate theories or assumptions with the goal of generalizing facts to the larger population, qualitative research is used to study concepts, thoughts, or experiences for the purpose of gaining the underlying reasons, motivations, and meanings behind human behavior .

What Are the Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Qualitative and quantitative research differs in terms of the methods they employ to conduct, collect, and analyze data. For example, qualitative research usually relies on interviews, observations, and textual analysis to explore subjective experiences and diverse perspectives. While quantitative data collection methods include surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis to gather and analyze numerical data. The differences between the two research approaches across various aspects are listed in the table below.

| Understanding meanings, exploring ideas, behaviors, and contexts, and formulating theories | Generating and analyzing numerical data, quantifying variables by using logical, statistical, and mathematical techniques to test or prove hypothesis | |

| Limited sample size, typically not representative | Large sample size to draw conclusions about the population | |

| Expressed using words. Non-numeric, textual, and visual narrative | Expressed using numerical data in the form of graphs or values. Statistical, measurable, and numerical | |

| Interviews, focus groups, observations, ethnography, literature review, and surveys | Surveys, experiments, and structured observations | |

| Inductive, thematic, and narrative in nature | Deductive, statistical, and numerical in nature | |

| Subjective | Objective | |

| Open-ended questions | Close-ended (Yes or No) or multiple-choice questions | |

| Descriptive and contextual | Quantifiable and generalizable | |

| Limited, only context-dependent findings | High, results applicable to a larger population | |

| Exploratory research method | Conclusive research method | |

| To delve deeper into the topic to understand the underlying theme, patterns, and concepts | To analyze the cause-and-effect relation between the variables to understand a complex phenomenon | |

| Case studies, ethnography, and content analysis | Surveys, experiments, and correlation studies |

Data Collection Methods