Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 15 August 2024

Exploration of first onsets of mania, schizophrenia spectrum disorders and major depressive disorder in perimenopause

- Lisa M. Shitomi-Jones ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-7433-0498 1 ,

- Clare Dolman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7466-1651 2 ,

- Ian Jones ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5821-5889 1 , 3 ,

- George Kirov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3427-3950 1 ,

- Valentina Escott-Price ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1784-5483 1 ,

- Sophie E. Legge ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6617-0289 1 &

- Arianna Di Florio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0338-2748 1

Nature Mental Health ( 2024 ) Cite this article

22 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Bipolar disorder

- Schizophrenia

Although the relationship between perimenopause and changes in mood has been well established, knowledge of risk of a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders associated with reproductive aging is limited. Here we investigate whether the perimenopause (that is, the years around the final menstrual period (FMP)) is associated with increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders compared with the late reproductive stage. Information on menopausal timing and psychiatric history was obtained from nurse-administered interviews and online questionnaires from 128,294 female participants within UK Biobank. Incidence rates of psychiatric disorders during the perimenopause (4 years surrounding the FMP) were compared with the reference premenopausal period (6–10 years before the FMP). The rates were calculated for major depressive disorder (MDD), mania, schizophrenia spectrum disorders and other diagnoses. Overall, of 128,294 participants, 753 (0.59%) reported their first onset of a psychiatric disorder during the late reproductive stage (incidence rate 1.53 per 1,000 person-years) and 1,133 (0.88%) during the perimenopause (incidence rate 2.33 per 1,000 person-years). Compared with the reference reproductive period, incidence rates of psychiatric disorders significantly increased during the perimenopause (incidence rate ratio (RR) of 1.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.39–1.67) and decreased back down to that observed in the premenopausal period in the postmenopause (RR of 1.09 (95% CI 0.98–1.21)). The effect was primarily driven by increased incidence rates of MDD, with an incidence RR of 1.30 (95% CI 1.16–1.45). However, the largest effect size at perimenopause was observed for mania (RR of 2.12 (95% CI 1.30–3.52)). No association was found between perimenopause and incidence rates of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (RR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.48–1.88)). In conclusion, perimenopause was associated with an increased risk of developing MDD and mania. No association was found between perimenopause and first onsets of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Major depression, physical health and molecular senescence markers abnormalities

Key subphenotypes of bipolar disorder are differentially associated with polygenic liabilities for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depressive disorder

Epidemiologic and genetic associations of female reproductive disorders with depression or dysthymia: a Mendelian randomization study

There are estimated to be greater than 945 million women and those assigned female at birth aged between 40 and 60 years in the world 1 . During perimenopause (the years around the final menstrual period (FMP)), approximately 80% of people develop neuropsychiatric symptoms, most commonly hot flushes, cognitive dysfunction, sleep disturbances and mood-related symptoms 2 . It has been suggested that perimenopause is also a high-risk period for the onset or exacerbation of psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder; although, research thus far has predominately measured only depressive symptoms 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . A two- to four-times greater risk of a depressive episode during perimenopause compared with the reproductive stage has been observed by the limited studies that have investigated MDD, even after controlling for other predictors and perimenopausal symptoms 8 , 9 , 10 . However, failure to account for multiple testing, retrospective design and focus on mild symptomatology have limited the generalizability of the results. Very little research has been conducted on the association between perimenopause and onset of disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Observations thus far have been limited to risk of recurrence in women with preexisting disorders and have shown that midlife in women is associated with worsening bipolar symptoms 11 , as well as an increased risk of hospitalizations for psychosis compared with men of the same age 12 . A major limitation of researching the association between reproductive aging and psychiatric disorders is related to the difficulties in obtaining reliable evaluations of ovarian aging, especially in epidemiological studies, with most studies using age as a proxy for age at FMP 13 . However, there is an over 20-year range variation in age at menopause, with research advocating that chronological age is not a valid proxy for menopausal status 14 , 15 , 16 . The UK Biobank represents a unique opportunity to study the effects of reproductive aging, with information on menopausal timing and deep longitudinal data collected on over 200,000 female participants recruited at 40–69 years of age 17 . Here, we focus on ‘late’ first onsets, because studies on the effect of reproductive aging on first-onset severe mental illness (that is, schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder) are lacking. This is likely due to the low prevalence and, therefore, difficulty to detect any effect in epidemiological studies specifically designed to study menopause. In this article, we aim to exploit a unique and specific asset of the UK Biobank: the combination of questions on first-onset psychiatric illness and age at FMP in an epidemiological study large enough to detect less prevalent, devastating outcomes, such as first incidence of bipolar disorder/schizophrenia, at a population level. The aim of this study is to test the hypothesis that perimenopause is a time of increased rate of first-onset psychiatric disorders, including MDD, mania and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, compared with the late reproductive stage.

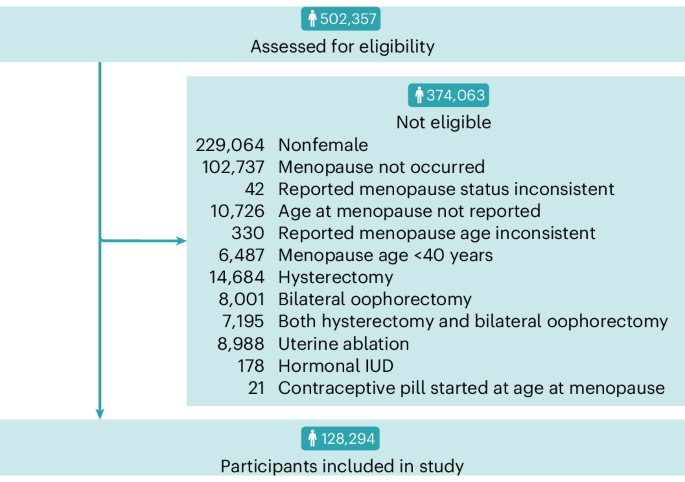

A total of 128,294 participants from the UK Biobank met inclusion criteria, as shown in Fig. 1 . The mean age at recruitment into this study was 59.6 years (standard deviation (s.d.) of 5.69 years) with an average follow-up period of 2.98 years (s.d. of 3.92 years) and mean age at menopause of 50.6 years of age (range of 40–68 years; s.d. of 4.00 years), as displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1 . Demographic characteristics of female participants, including self-reported ethnicity, are presented in Table 1 . As presented in Table 2 , a total of 753 participants (0.59%) had a first onset of a psychiatric disorder 6–10 years before the FMP (premenopause period), 1,133 participants (0.88%) between 2 years prior and 2 years following FMP (perimenopause) and 637 participants (0.50%) 6–10 years following the FMP (postmenopause), with incidence rates per 1,000 person-years of 1.53, 2.33 and 1.66, respectively. Trends in the number of new onsets of each psychiatric disorder for both female and male participants are displayed in Fig. 2 .

Please note that each exclusion criterion was implemented sequentially, with the number of participants removed at each stage calculated on the basis of the participants remaining after the previous criteria had been applied.

a , Female participants for MDD (left), mania (middle left), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (middle right) and other diagnoses (right). b , Male participants for MDD (left), mania (middle left), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (middle right) and other diagnoses (right). Please note that not all participants were followed up for 10 years after the FMP (or matched ‘FMP’ proxy for male participants), and thus, later numbers of new onsets are likely to be underestimated.

The perimenopause was associated with a significant increase in the incidence rates of psychiatric disorders compared with the premenopause period (incidence rate ratio (RR) of 1.52 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.39–1.67); Table 2 ). During the postmenopause, the incidence rate decreased back down to that observed in the premenopause period (RR of 1.09 (95% CI 0.98–1.21)).

Disorder-specific analyses

MDD was found to have a higher incidence rate during the perimenopause compared with the premenopause stage, with a RR of 1.30 (95% CI 1.16–1.45) (Fig. 3 and Table 2 ). The incidence rate of MDD became significantly lower in the postmenopause compared with the premenopause (RR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.59–0.78)).

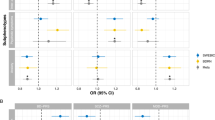

The dots indicate the incidence RR calculated relative to the premenopausal period (6–10 years before FMP). The whiskers indicate 95% CIs. Total sample sizes analyzed for each disorder are as follows: MDD ( n = 39,800), mania ( n = 128,105), schizophrenia spectrum disorders ( n = 128,170) and other diagnoses ( n = 127,292). Perimenopause is between 2 years before and 2 years after FMP, and postmenopause is 6–10 years after FMP.

The incidence rate of mania significantly increased in the perimenopause compared with the premenopause (RR of 2.12 (95% CI 1.30–3.52)), to then return to the premenopause level during the postmenopause (RR of 0.98 (95% CI 0.51–1.86)).

Perimenopause was not found to be significantly associated with a change in incidence rate of schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared with the premenopause stage (RR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.48–1.88)), though rates were found to be lower during the postmenopause (RR of 0.37 (95% CI 0.12–0.96)).

Both perimenopause and postmenopause were found to be significantly associated with an increased incidence rate of other diagnoses compared with the premenopause, with incidence RRs of 2.10 (95% CI 1.78–2.49) and 2.08 (95% CI 1.74–2.49), respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses did not detect any effect of potential confounders on results. Compared with the premenopause, an association between perimenopause and an increased incidence rate of psychiatric disorders was observed in those with low and high Townsend Deprivation Indexes, those of healthy, preobese and obese body mass index (BMI) categories, across all six alcohol intake frequency categories and in both previous and never smokers (Supplementary Table 1 ). Perimenopause was not found to be significantly associated with an increase in incidence rate of psychiatric disorders compared with the premenopause in those with underweight BMI or current smokers.

Analysis of male participants

Demographic characteristics of male participants are available in Supplementary Table 2 . No individual disorder had any significant peak of incidence at the interval period that matched ‘perimenopause’ (Extended Data Fig. 1 ). First onsets of MDD had a similar pattern in male and female participants; although, this did not reach statistical significance in the male sample during the ‘perimenopause’ proxy (RR of 1.13 (95% CI 1.00–1.29); Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3 ). In male participants, no increase in incidence rate was observed during the ‘perimenopause’ proxy compared with the ‘premenopause’ proxy for mania (RR of 0.88 (95% CI 0.55–1.41)) nor schizophrenia spectrum disorders (RR of 0.57 (95% CI 0.26–1.22); Supplementary Table 3 ). Similarly to the female sample, both the perimenopause and postmenopause proxies in male participants were associated with an increased rate of other diagnoses compared with the premenopause proxy, with incidence RRs of 1.44 (95% CI 1.20–1.74) and 1.36 (95% CI 1.11–1.67), respectively.

Our results show that the perimenopause is a period of increased risk of first-onset psychiatric disorders, with compelling evidence for a specific link with mania. We found that participants without previous history of mania were over twice as likely to develop mania for the first time in the perimenopause than in the late reproductive stage. The increased risk was specific for the perimenopause, as the rates of first-onset mania returned to premenopause levels in the postmenopause.

Main findings

Our results highlight the importance of considering the FMP rather than chronological age in both clinical practice and research concerning mental health and reproductive aging. Previous studies using chronological age had not been able to detect the effect of perimenopause on mania/bipolar disorder 18 . Given the 20-year range variation in age at FMP 14 , inferring age at menopause on solely chronological age can lead to errors and, in research, to false negatives. The disease-specific and narrow time window (4 years) of increased risk for mania also suggests that specific changes associated with the perimenopause may trigger mania in people without previous psychiatric history of mania. The lack of any association in male participants corroborates the idea that sex-specific factors are associated with the first occurrence of mania at the time of the perimenopause. For bipolar disorder and mania, evidence suggests a trimodal distribution of age of onset, reflecting possible biological heterogeneity 19 . By selecting a period of 4–10 years prior the FMP as reference, our analyses focused on the late onset group, providing for the first time direct evidence of a possible link between mania and the hormonal fluctuations of the perimenopause. Intriguingly, one of the most robust pieces of evidence in psychiatry is that of the association between mania and the first few weeks after childbirth, with a 23 times increased risk of first-onset mania in the 30 days postpartum compared with 12 months after giving birth 20 . Although the effect we found for perimenopause is much smaller than that observed for childbirth, our results support the theory that there is a link between mania/bipolar disorder and reproductive events beyond childbirth. It has been suggested that menopausal mood disorders could be predicted by sensitivity to estradiol, with 27% of individuals sensitive to either withdrawal (7%) or absolute change (20%) in estradiol levels 21 . As the postpartum period is associated with a sharp decline in estradiol levels, it may be that individuals with an estradiol-sensitive predisposition may have already developed an onset of mania during postpartum, reducing the number of first onsets at perimenopause.

Contrary to mania, we did not find any specific association between schizophrenia spectrum disorders and the perimenopause. While the lack of effect may be due to the small sample size, we did find that the incidence rate of schizophrenia spectrum disorder was significantly lower in the postmenopause compared with the premenopausal stage. Our findings, therefore, do not support the widely discussed hypothesis that hypoestrogenism may trigger the first onset of schizophrenia but are in line with those of a large collaborative study on over 130,000 incident cases of schizophrenia, showing a decline in new onsets in women after the age of 40 years 22 .

Our results corroborate findings from previous studies that have observed an increased risk of depression in the perimenopause 3 , 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 . The effect was smaller than that for mania, but the CIs were narrower, as there were more people who developed major depression than people who developed mania. Interestingly, while rates of first-onset MDD decreased in the postmenopause, rates of first-onset depressive symptoms remained high in the postmenopause (Supplementary Table 4 ). The mechanisms underpinning the link between first-onset depressive symptoms and reproductive aging may, therefore, be complex and include not only hormonal changes associated with the perimenopause, but also biopsychosocial challenges associated with aging. Depression is likely an umbrella term for several conditions with heterogeneous disease pathways. It is then possible that onsets at different reproductive stages are linked to different mechanisms. Given that our study ascertained age at first diagnosis by a health care professional, it is also possible that some participants who experienced depressive symptoms during the perimenopause delayed seeking help or that their symptoms had become severe enough to seek help only in the postmenopause. Curiously, although the male analysis revealed a similar trend of depression risk, upon closer inspection of the number of onsets around the FMP proxy (Fig. 2 ), they lack the sharp peak present in the female analysis. The present study observed a decline in risk of a first onset of MDD during the postmenopausal period compared with premenopause in both the female and male proxy analysis. Although older populations often have high prevalence of depression 23 , with the course of MDD becoming poorer with age 24 , our results are in line with previous studies which observe a decline in first-ever onsets of depression in the decade following the average age at FMP (~50 years of age) 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 . As such, it may be that while the onset of depression occurs during perimenopause or earlier in life, some individuals may remain depressed during the postmenopause, leading to a high prevalence.

Strengths and limitations

Using data from the UK Biobank has allowed us to use a reported age at menopause to determine reproductive timing and, thus, estimate time periods to capture the pre-, peri- and postmenopausal life stages. This is a major strength over many previous studies, which have often used chronological age as a proxy for menopause despite the large variability in reproductive timing between individuals 14 . However, the UK Biobank does not include additional information on the menstrual cycle, which would provide more fine grain information on the stages of reproductive aging and menopausal symptoms. Aware of this UK Biobank limitation and of the variability in the length of the early menopause transition, we focused our analyses on the late menopausal transition and the early postmenopause, as: (1) they have less variability in their length 29 and (2) previous studies have suggested that the late menopause transition is the period of highest risk of new-onset depression 9 . We then chose the reference period of 6–10 years before the FMP, as only very few people will experience a late menopausal transition longer than 6 years 29 .

Another unique strength of the UK Biobank is that the large sample size, the collection on information on FMP and the cohort design allow inference on a range of psychiatric disorders, including less prevalent and more severe ones, such as mania and psychosis. However, due to the particularly low prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, we were not able to run fine-grained analyses considering the different disorders separately. Further replication of our results should be carried out before definitive conclusions can be drawn. Additionally, representativeness of UK Biobank has been an area of controversy, with diverging views on the validity of its measures of association 30 , 31 . Our sensitivity analyses show the robustness of our findings across several socioeconomic, health and lifestyle characteristics. The increased incidence of psychiatric conditions at perimenopause were present across different levels of the Townsend Deprivation Index, BMI categories, alcohol intake frequencies and in previous and never smokers. Additionally, we note that our study design selects for those without a diagnosis of severe mental illness before 10 years before the FMP and, thus, will be ‘healthier’ by definition as is the design of the study, rather than due to an unintended selection bias.

We emphasize that the incidence and prevalence estimates of our study are not the focus of the paper and should not be taken as representative of the UK population as a whole. Moreover, our study focused on the effect of the perimenopause on the first incidence of psychiatric disorders. By using as a reference group people 10 years before their FMP, by design, we selected a population that has reached the middle age without any psychiatric diagnosis. This study design has the advantage of excluding the well-established peak of severe psychiatric disorders in early adulthood, which would mask the effect of the perimenopause.

Directions for future work

Our study focused on the first onset of psychiatric disorders during the perimenopause. The study of recurrence of preexisting psychiatric disorders was beyond the scope of this paper and would have required a different study design. Further research focusing on large cohorts of people with previous history of mental illness is necessary to improve their risk prediction and mitigation associated with reproductive aging.

Conclusions

Our results highlight the importance of diagnostic accuracy in the assessment of psychiatric phenomena associated with aging. First, research and clinicians should consider interpersonal variability in reproductive aging rather than use demographic age as a proxy. Second, differential diagnosis is key, and not all psychiatric symptoms with onset at the perimenopause should be considered depressive symptoms etiologically related to the perimenopause. Mechanistic research needs to differentiate between clinical manifestation that are mostly epiphenomena from those that may be triggered by the physiological changes associated with reproductive aging. Clinically, the link with mania was particularly striking and significant: although first-onset bipolar disorder is usually associated with younger age, the perimenopause represents a period of increased risk of manic onset in those without previous psychiatric history of mania. Primary care physicians should be aware of this late onset presentation of bipolar disorder to avoid the risks associated with a delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis with depression. Antidepressants without mood stabilizers can in fact precipitate manic episodes in those with bipolar diathesis 32 .

Study design and participants

The initial sample consisted of 502,357 individuals from the UK Biobank 17 . The UK Biobank is a large-scale biomedical database designed to enable research into genetic and environmental determinants of disease. Participants were recruited at 40–69 years of age between 2006 and 2010 and undertook extensive data collection. Measurements included assessment center visits, genotyping and longitudinal follow-up of health outcomes including linkage to medical records. The North West Multi-Centre Ethics Committee granted ethical approval to the UK Biobank, and all participants provided written informed consent. This study was conducted under project number 13310.

Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using interviews and a self-report web-based questionnaire (the UK Biobank mental health questionnaire). Interviews were conducted by trained nurses and included questions on past and current medical conditions and date of diagnosis. The mental health questionnaire was based on the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form 33 and integrated elements of other validated tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (9-question version), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire 7-item 34 and bespoke additional questions. Although some participants also have linked medical primary health care records and hospital admission records, these data were not used in the present study as only more recent records are available electronically; thus, admission dates were not trusted as valid proxies for first onsets of psychiatric disorders.

Sample demographic variables include ethnicity. This was self-reported via touchscreen questionnaire at the initial assessment center visit by the question: ‘What is your ethnic background?’.

Selection of individuals for analysis

Figure 1 illustrates sample selection. The UK Biobank dataset was restricted to participants of female sex, as reported in the NHS central registry at the time of recruitment; although, in some instances this was updated by the participant (field identification (ID) 31). Of the 502,357 participants in the UK Biobank, 273,293 (54.4%) were of female sex. The sample was then limited to the 170,556 participants (62.4%) that had reported menopause occurrence (field ID 2724), which is defined as the cessation of menstrual periods for 12 months 29 . At each assessment center visit, participants were asked to self-report if menopause had occurred via touchscreen questionnaire (field ID 2724). Of the 22,971 individuals (13.5%) who had answered this question at multiple assessment center visits, 42 individuals (0.18%) who answered ‘yes’ but then responded ‘no’ to the same question at a subsequent visit were excluded, leaving 170,514 participants in the sample. Age at menopause, defined as age at the FMP, was asked via touchscreen questionnaire (field ID 3581) if the participant had responded ‘yes’ when asked if menopause had occurred. As this question was administered at each assessment center visit, 13,311 participants (7.81%) answered the question more than once. Of these, 442 participants (3.32%) reported different ages when asked again, and 330 (2.48%) whose reported ages at menopause varied by two or more years were excluded from the study due to potential unreliability. For the 112 individuals (0.84%) with multiple reported ages at menopause that did not vary by two or more years, the response from the earliest available assessment center visit was taken to reduce the probability of recall bias. A total of 10,726 participants (6.30%) had no age at menopause reported, having responded, ‘do not know’ or ‘prefer not to answer’ and were subsequently excluded from the study. A further 6,487 (4.07%) reported an age at menopause (field ID 3581) before 40 years of age and were excluded, as primary ovarian insufficiency is associated with major depression 35 , leaving 152,971 participants in the sample. A total of 15,490 participants (10.1%) who reported a hysterectomy (field ID 3591) or a bilateral oophorectomy (field ID 2834) were excluded from the study as these procedures have also been linked with an increased risk of depression 36 , 37 , 38 . Those who had undergone uterine ablations (8,988) were excluded, as this can cause cessation of menstrual periods (field ID 41272, OPCS4 codes: Q07, Q08, Q10, Q16). As contraceptive use can also cause cessation of menstrual periods, 199 participants (0.15%) who reported using a hormonal intrauterine device (IUD) or who reported starting oral contraceptives at the same age they experienced menopause were excluded from analysis, resulting in a sample size of 128,294.

Diagnostic criteria

First onsets of MDD, mania, schizophrenia spectrum disorders and an ‘other diagnoses’ category were investigated in the present study. These disorders were chosen on the basis of previous literature investigating the effect of childbirth 20 , as these events both cause changes in sex hormone levels, and thus, new onsets of disorders during these periods may share hormone-driven etiological pathways 2 , 21 .

The diagnosis of MDD was based on answers from the online mental health questionnaire and mapped on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (DSM-5) criteria. Such approach has been previously validated by Cai and colleagues 39 , who found this approach to have higher SNP-based heritability than any other definition of depression available in the UK Biobank, including medical record-based criteria. Details of this diagnostic criteria are available in Supplementary Note: Diagnostic Criteria . Briefly, a classification of MDD required at least two cardinal symptoms, as well as at least five total symptoms, and excluded individuals with a history of substance abuse and/or manic/psychotic conditions. Age at first onset was defined as the age at first episode of depression (field ID 20433). Analyses of individuals self-reporting depressive symptoms are available in Supplementary Note: Diagnostic Criteria (Supplementary Table 4 ).

The diagnoses of mania/bipolar/manic–depression (henceforth referred to as ‘mania’), schizophrenia spectrum disorders and an ‘other diagnoses’ category were based on the nurse-conducted interviews (field IDs 20002 and 20009). Individuals who reported having schizophrenia at interview were combined with individuals who reported a diagnosis of schizophrenia or ‘any other type of psychosis or psychotic illness’ in those who completed the mental health questionnaire (field IDs 20544 and 20461) to form a ‘schizophrenia spectrum disorders’ group. The ‘other diagnoses’ group included participants who reported any of the following conditions at a nurse-conducted interview: ‘anxiety/panic attacks’, ‘substance abuse/dependency’, ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’, anorexia/bulimia/other eating disorder’, ‘stress’, ‘obsessive compulsive disorder’ or ‘insomnia’.

Finally, a combined ‘psychiatric disorder’ group was formed of all the above diagnoses combined. In the case of the combined ‘psychiatric disorder’ group, if multiple diagnoses were present in a single participant, the earliest age at onset was prioritized.

For each diagnosis group, individuals were removed from analysis if they met the diagnostic criteria but did not have onset age data available, as detailed in Supplementary Note: Diagnostic Criteria .

Statistical analysis

Age at first onset of any given psychiatric disorder relative to age at FMP was calculated as self-reported age at menopause (field ID 3581) subtracted from the age at onset. These values were grouped to form the following three life stages: premenopause (6–10 years before the FMP), perimenopause (2 years before and 2 years following FMP) and postmenopause (6–10 years after the FMP). The values between 2 and 6 years from the FMP were excluded to increase distinction between the time periods and to minimize the likelihood of misclassification due to inaccuracies in menopausal timing. The premenopause represents the reference life stage against which the other life stages were compared. The late reproductive stage (6–10 years before the FMP) was used as the refence premenopausal period to reduce the effect of recall bias and to minimize inclusion of adolescent and postnatal onsets within the reference period.

A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used for each diagnosis group to determine the likelihood of disorder onset at each life stage. This was conducted using the ‘survival’ R package in RStudio, version 4.2.1 (refs. 40 , 41 ). Incidence rates in person-years for each time period were calculated as the number of cases divided by four times the total number of cases and controls, as each time period was 4 years long. Incidence RRs were calculated to compare the rate of first onsets in the perimenopause and postmenopause compared with the premenopausal stage, using the two-sided ‘rateratio.test’ R package 42 , with a confidence level of 0.95. The false discovery rate correction was applied to correct for 50 tests (10 tests in Table 2 , 30 tests in Supplementary Table 1 , 8 tests in Supplementary Table 3 and 2 tests in Supplementary Table 4 ) 43 . We provide P values both with and without correction for multiple testing.

Sensitivity analyses

Previous literature has observed that the UK Biobank participants differ from UK Census data on several socioeconomic, health and lifestyle characteristics 30 . Participants have been found to be more likely to live in less deprived geographical areas and less likely to be obese, to currently smoke or to drink alcohol daily. To consider the effect of this sampling bias, we investigated the effects of Townsend Deprivation Index, BMI, smoking status and alcohol intake frequency on the findings of the present study by stratifying the sample on these characteristics. Further details are available in Supplementary Note: Sensitivity Analysis .

Analyses of male participants

It is possible that the observed effects may not be driven by the hormonal fluctuations that characterized the perimenopause. Rather, they could be driven by age or by unknown ascertainment and assessment bias. The same analyses were, therefore, conducted in male participants enrolled in UK Biobank.

First, we matched male participants to female participants on the basis of their most recent age that they came into the assessment center (field ID 21003). Then, for each male participant, we constructed a timeline centered around the age at the FMP of their matched female participant. So, for example, if we matched a female and male participant based on the age at the last assessment of 62 and the female participant had an age at the FMP of 50 years, we then centered the timeline of the male participant around 50. The three time periods considered as a proxy in this case would be 40–44 years for premenopause, 48–52 years for perimenopause and 56–60 years for postmenopause. This was carried out to account for the variation and distribution of menopausal timing in female participants to consider the effect of attrition based on the age of most recent follow-up and to create equal sample sizes to homogenize the statistical power. This resulted in 128,294 male participants being included in analysis. All following statistical analyses mirrored the analyses conducted in the female sample.

Patient and public involvement

People with lived experience were involved in the design of the study, in the interpretation of the results and in the writing of the manuscript. C.D., a researcher with lived experience and coauthor on the publication, provided expertise and voiced the issues experienced by people affected by severe mental illness. In her roles within the charities Bipolar UK and Action on Postpartum Psychosis, C.D. has provided support to women with lived experience of illness during the perimenopause over several years and has worked as patient and public involvement lead. Moreover, the design of the current study was informed by a Bipolar UK survey designed and conducted by C.D., which received over 1,000 responses,

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the data used in this study, both raw and derived, are available from the UK Biobank ( https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ ). This study was conducted under project number 13310. Our access to the data does not allow for data redistribution.

Code availability

Code used for analysis is available online at https://lms-j.github.io/perimeno-first-onsets/ .

World Population Prospects 2022. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ (2022).

Brinton, R. D., Yao, J., Yin, F., Mack, W. J. & Cadenas, E. Perimenopause as a neurological transition state. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11 , 393–405 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tangen, T. & Mykletun, A. Depression and anxiety through the climacteric period: an epidemiological study (HUNT-II). J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 29 , 125–131 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Lin, H.-L., Hsiao, M.-C., Liu, Y.-T. & Chang, C.-M. Perimenopause and incidence of depression in midlife women: a population-based study in Taiwan. Climacteric 16 , 381–386 (2013).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Timur, S. & Sahin, N. H. The prevalence of depression symptoms and influencing factors among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause 17 , 545–551 (2010).

Bromberger, J. T. et al. Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J. Affect. Disord. 103 , 267–272 (2007).

Maartens, L. W. F., Knottnerus, J. A. & Pop, V. J. Menopausal transition and increased depressive symptomatology: a community based prospective study. Maturitas 42 , 195–200 (2002).

Freeman, E. W., Sammel, M. D., Boorman, D. W. & Zhang, R. Longitudinal pattern of depressive symptoms around natural menopause. JAMA Psychiatry 71 , 36–43 (2014).

Schmidt, P. J., Haq, N. & Rubinow, D. R. A longitudinal evaluation of the relationship between reproductive status and mood in perimenopausal women. Am. J. Psychiatry 161 , 2238–2244 (2004).

Bromberger, J. T. & Kravitz, H. M. Mood and menopause: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) over 10 years. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 38 , 609–625 (2011).

Perich, T., Ussher, J. & Meade, T. Menopause and illness course in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 19 , 434–443 (2017).

Sommer, I. E. et al. Women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders after menopause: a vulnerable group for relapse. Schizophr. Bull. 49 , 136–143 (2023).

Culbert, K. M., Thakkar, K. N. & Klump, K. L. Risk for midlife psychosis in women: critical gaps and opportunities in exploring perimenopause and ovarian hormones as mechanisms of risk. Psychol. Med. 52 , 1612–1620 (2022).

Brinton, R. D. in Brocklehurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology 8th edn, Ch. 13 (eds Fillit H., Rockwood K. and Young J.) 76–81 (Elsevier, 2017).

Gold, E. B. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 38 , 425–440 (2011).

Chan, S., Gomes, A. & Singh, R. S. Is menopause still evolving? Evidence from a longitudinal study of multiethnic populations and its relevance to women’s health. BMC Womens Health 20 , 74 (2020).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12 , e1001779 (2015).

Kennedy, N. et al. Gender differences in incidence and age at onset of mania and bipolar disorder over a 35-year period in Camberwell, England. Am. J. Psychiatry 162 , 257–262 (2005).

Bolton, S., Warner, J., Harriss, E., Geddes, J. & Saunders, K. E. A. Bipolar disorder: trimodal age-at-onset distribution. Bipolar Disord. 23 , 341–356 (2021).

Munk-Olsen, T., Laursen, T. M., Pedersen, C. B., Mors, O. & Mortensen, P. B. New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA 296 , 2582–2589 (2006).

Gordon, J. L., Sander, B., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A. & Tottenham, L. S. Mood sensitivity to estradiol predicts depressive symptoms in the menopause transition. Psychol. Med. 51 , 1733–1741 (2021).

van der Werf, M. et al. Systematic review and collaborative recalculation of 133,693 incident cases of schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 44 , 9–16 (2014).

Zenebe, Y., Akele, B., W/Selassie, M. & Necho, M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 20 , 55 (2021).

Schaakxs, R. et al. Associations between age and the course of major depressive disorder: a 2-year longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 5 , 581–590 (2018).

Zisook, S. et al. Effect of age at onset on the course of major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 , 1539–1546 (2007).

Zhu, T. et al. Admixture analysis of age at onset in major depressive disorder. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 34 , 686–691 (2012).

Pedersen, C. B. et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71 , 573–581 (2014).

Plana-Ripoll, O. et al. Temporal changes in sex- and age-specific incidence profiles of mental disorders—a nationwide study from 1970 to 2016. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 145 , 604–614 (2022).

Harlow, S. D. et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 , 1159–1168 (2012).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186 , 1026–1034 (2017).

Keyes, K. M. & Westreich, D. UK Biobank, big data, and the consequences of non-representativeness. Lancet 393 , 1297 (2019).

Viktorin, A. et al. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am. J. Psychiatry 171 , 1067–1073 (2014).

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Mroczek, D., Ustun, B. & Wittchen, H.-U. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 7 , 171–185 (1998).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 32 , 345–359 (2010).

Schmidt, P. J. et al. Depression in women with spontaneous 46, XX primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96 , E278–E287 (2011).

Choi, H. G., Rhim, C. C., Yoon, J. Y. & Lee, S. W. Association between hysterectomy and depression: a longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Menopause 27 , 543–549 (2020).

Kim, H. et al. Increased risk of depression before and after unilateral or bilateral oophorectomy: a self-controlled case series study using a nationwide cohort in South Korea. J. Affect. Disord. 285 , 47–54 (2021).

Rocca, W. A. et al. Long-term risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause 25 , 1275–1285 (2018).

Cai, N. et al. Minimal phenotyping yields genome-wide association signals of low specificity for major depression. Nat. Genet. 52 , 437–447 (2020).

Therneau, T. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (2022).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing https://www.R-project.org/ (2022).

Fay, M. rateratio.test: exact rate ratio test. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rateratio.test (2022).

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. The Control of the False Discovery Rate in Multiple Testing Under Dependency. Ann. Stat. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013699998 (2001).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for funding from the Medical Research Council (grant MR/W004658/1), awarded to Cardiff University and the National Centre for Mental Health, for supporting this research. A.D.F. is also funded by the European Research Council (grant 947763). S.E.L. is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01MH124873). V.E.-P. is supported by the Medical Research Council (grants UKDRI-3003 and MR/Y004094/1). We are also grateful to the participants and staff of the UK Biobank for their time in producing the data used in this study. We thank M. Hamshere for her comments and suggestions, which helped to refine this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Division of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK

Lisa M. Shitomi-Jones, Ian Jones, George Kirov, Valentina Escott-Price, Sophie E. Legge & Arianna Di Florio

Bipolar UK, London, UK

Clare Dolman

National Centre for Mental Health, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.D.F., C.D., G.K. and I.J. conceptualized the study and acquired funding. Data curation and data analysis were carried out by L.M.S.-J. and supervised by S.E.L., V.E.-P. and A.D.F. L.M.S.-J. and S.E.L. had access to and verified the data. L.M.S.-J. and A.D.F. prepared the manuscript. Review and editing of the manuscript were conducted by L.M.S.-J., C.D., G.K., I.J., V.E.-P., S.E.L. and A.D.F. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. The study sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation or submission for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arianna Di Florio .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Mental Health thanks Veerle Bergink and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended data fig. 1 incidence rate ratios of psychiatric disorders for male participants during matched ‘perimenopause’ and ‘postmenopause’ proxies, relative to the matched ‘premenopause’ period proxy..

Note that age-based classifications were based on values from matched female participants. Dots indicate the incidence rate ratio calculated relative to the premenopausal period proxy (6-10 years before the assigned FMP). Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals. Total sample sizes analysed for each disorder are as follows: major depressive disorder (n = 37 719); mania (n = 128 131), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (n = 128 108); other diagnoses (n = 127 449). Perimenopause = Between −2 years before and 2 years after FMP; Postmenopause = 6-10 years after FMP.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Incidence rate ratios of psychiatric disorders in female participants during the perimenopause (2 years prior - 2 years following FMP) compared to male participants during the matched ‘perimenopause’ proxy (2 years prior - 2 years following assigned FMP).

Note that age at FMP in male participants was based on values from matched female participants. Dots indicate the incidence rate ratio calculated relative to the premenopausal period (6-10 years before FMP). Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals. Sample sizes analysed for each disorder are as follows: major depressive disorder (n female = 39 800, n male = 37 719); mania (n female = 128 105, n male = 128 131), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (n female = 128 170, n male = 128 108); other diagnoses (n female = 127 292, n male = 127 449). Perimenopause = Between −2 years before and 2 years after FMP; Postmenopause = 6-10 years after FMP.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary methods (diagnostic criteria and sensitivity analysis), Tables 1–4 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shitomi-Jones, L.M., Dolman, C., Jones, I. et al. Exploration of first onsets of mania, schizophrenia spectrum disorders and major depressive disorder in perimenopause. Nat. Mental Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00292-4

Download citation

Received : 13 November 2023

Accepted : 24 June 2024

Published : 15 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00292-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Module 11: Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

Case studies: schizophrenia spectrum disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify schizophrenia and psychotic disorders in case studies

Case Study: Bryant

Thirty-five-year-old Bryant was admitted to the hospital because of ritualistic behaviors, depression, and distrust. At the time of admission, prominent ritualistic behaviors and depression misled clinicians to diagnose Bryant with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Shortly after, psychotic symptoms such as disorganized thoughts and delusion of control were noticeable. He told the doctors he has not been receiving any treatment, was not on any substance or medication, and has been experiencing these symptoms for about two weeks. Throughout the course of his treatment, the doctors noticed that he developed a catatonic stupor and a respiratory infection, which was identified by respiratory symptoms, blood tests, and a chest X-ray. To treat the psychotic symptoms, catatonic stupor, and respiratory infection, risperidone, MECT, and ceftriaxone (antibiotic) were administered, and these therapies proved to be dramatically effective. [1]

Case Study: Shanta

Shanta, a 28-year-old female with no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, was sent to the local emergency room after her parents called 911; they were concerned that their daughter had become uncharacteristically irritable and paranoid. The family observed that she had stopped interacting with them and had been spending long periods of time alone in her bedroom. For over a month, she had not attended school at the local community college. Her parents finally made the decision to call the police when she started to threaten them with a knife, and the police took her to the local emergency room for a crisis evaluation.

Following the administration of the medication, she tried to escape from the emergency room, contending that the hospital staff was planning to kill her. She eventually slept and when she awoke, she told the crisis worker that she had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) a month ago. At the time of this ADHD diagnosis, she was started on 30 mg of a stimulant to be taken every morning in order to help her focus and become less stressed over the possibility of poor school performance.

After two weeks, the provider increased her dosage to 60 mg every morning and also started her on dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets (10 mg) that she took daily in the afternoon in order to improve her concentration and ability to study. Shanta claimed that she might have taken up to three dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets over the past three days because she was worried about falling asleep and being unable to adequately prepare for an examination.

Prior to the ADHD diagnosis, the patient had no known psychiatric or substance abuse history. The urine toxicology screen taken upon admission to the emergency department was positive only for amphetamines. There was no family history of psychotic or mood disorders, and she didn’t exhibit any depressive, manic, or hypomanic symptoms.

The stimulant medications were discontinued by the hospital upon admission to the emergency department and the patient was treated with an atypical antipsychotic. She tolerated the medications well, started psychotherapy sessions, and was released five days later. On the day of discharge, there were no delusions or hallucinations reported. She was referred to the local mental health center for aftercare follow-up with a psychiatrist. [2]

Another powerful case study example is that of Elyn R. Saks, the associate dean and Orrin B. Evans professor of law, psychology, and psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California Gould Law School.

Saks began experiencing symptoms of mental illness at eight years old, but she had her first full-blown episode when studying as a Marshall scholar at Oxford University. Another breakdown happened while Saks was a student at Yale Law School, after which she “ended up forcibly restrained and forced to take anti-psychotic medication.” Her scholarly efforts thus include taking a careful look at the destructive impact force and coercion can have on the lives of people with psychiatric illnesses, whether during treatment or perhaps in interactions with police; the Saks Institute, for example, co-hosted a conference examining the urgent problem of how to address excessive use of force in encounters between law enforcement and individuals with mental health challenges.

Saks lives with schizophrenia and has written and spoken about her experiences. She says, “There’s a tremendous need to implode the myths of mental illness, to put a face on it, to show people that a diagnosis does not have to lead to a painful and oblique life.”

In recent years, researchers have begun talking about mental health care in the same way addiction specialists speak of recovery—the lifelong journey of self-treatment and discipline that guides substance abuse programs. The idea remains controversial: managing a severe mental illness is more complicated than simply avoiding certain behaviors. Approaches include “medication (usually), therapy (often), a measure of good luck (always)—and, most of all, the inner strength to manage one’s demons, if not banish them. That strength can come from any number of places…love, forgiveness, faith in God, a lifelong friendship.” Saks says, “We who struggle with these disorders can lead full, happy, productive lives, if we have the right resources.”

You can view the transcript for “A tale of mental illness | Elyn Saks” here (opens in new window) .

- Bai, Y., Yang, X., Zeng, Z., & Yang, H. (2018). A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. BMC psychiatry , 18(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1655-5 ↵

- Henning A, Kurtom M, Espiridion E D (February 23, 2019) A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Cureus 11(2): e4126. doi:10.7759/cureus.4126 ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Wallis Back for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A tale of mental illness . Authored by : Elyn Saks. Provided by : TED. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6CILJA110Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Authored by : Ashley Henning, Muhannad Kurtom, Eduardo D. Espiridion. Provided by : Cureus. Located at : https://www.cureus.com/articles/17024-a-case-study-of-acute-stimulant-induced-psychosis#article-disclosures-acknowledgements . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Elyn Saks. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elyn_Saks . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. Authored by : Yuanhan Bai, Xi Yang, Zhiqiang Zeng, and Haichen Yangcorresponding. Located at : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5851085/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

Our Most Troubling Madness: Case Studies in Schizophrenia Across Cultures

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options.

Information

Published in.

- Schizophrenia

- Case Studies

- Clinical Anthropology

- Social Defeat

- Serious Psychotic Disorder

- Diagnostic Neutrality

Funding Information

Export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - American Journal of Psychiatry

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Schizophrenia case studies: putting theory into practice

This article considers how patients with schizophrenia should be managed when their condition or treatment changes.

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Treatments for schizophrenia are typically recommended by a mental health specialist; however, it is important that pharmacists recognise their role in the management and monitoring of this condition. In ‘ Schizophrenia: recognition and management ’, advice was provided that would help with identifying symptoms of the condition, and determining and monitoring treatment. In this article, hospital and community pharmacy-based case studies provide further context for the management of patients with schizophrenia who have concurrent conditions or factors that could impact their treatment.

Case study 1: A man who suddenly stops smoking

A man aged 35 years* has been admitted to a ward following a serious injury. He has been taking olanzapine 20mg at night for the past three years to treat his schizophrenia, without any problems, and does not take any other medicines. He smokes 25–30 cigarettes per day, but, because of his injury, he is unable to go outside and has opted to be started on nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in the form of a patch.

When speaking to him about his medicines, he appears very drowsy and is barely able to speak. After checking his notes, it is found that the nurses are withholding his morphine because he appears over-sedated. The doctor asks the pharmacist if any of the patient’s prescribed therapies could be causing these symptoms.

What could be the cause?

Smoking is known to increase the metabolism of several antipsychotics, including olanzapine, haloperidol and clozapine. This increase is linked to a chemical found in cigarettes, but not nicotine itself. Tobacco smoke contains aromatic hydrocarbons that are inducers of CYP1A2, which are involved in the metabolism of several medicines [1] , [2] , [3] . Therefore, smoking cessation and starting NRT leads to a reduction in clearance of the patient’s olanzapine, leading to increased plasma levels of the antipsychotic olanzapine and potentially more adverse effects — sedation in this case.

Patients who want to stop, or who inadvertently stop, smoking while taking antipsychotics should be monitored for signs of increased adverse effects (e.g. extrapyramidal side effects, weight gain or confusion). Patients who take clozapine and who wish to stop smoking should be referred to their mental health team for review as clozapine levels can increase significantly when smoking is stopped [3] , [4] .

For this patient, olanzapine is reduced to 15mg at night; consequently, he seems much brighter and more responsive. After a period on the ward, he has successfully been treated for his injury and is ready to go home. The doctor has asked for him to be supplied with olanzapine 15mg for discharge along with his NRT.

What should be considered prior to discharge?

It is important to discuss with the patient why his dose was changed during his stay in hospital and to ask whether he intends to start smoking again or to continue with his NRT. Explain to him that if he wants to begin, or is at risk of, smoking again, his olanzapine levels may be impacted and he may be at risk of becoming unwell. It is necessary to warn him of the risk to his current therapy and to speak to his pharmacist or mental health team if he does decide to start smoking again. In addition, this should be used as an opportunity to reinforce the general risks of smoking to the patient and to encourage him to remain smoke-free.

It is also important to speak to the patient’s community team (e.g. doctors, nurses), who specialise in caring for patients with mental health disorders, about why the olanzapine dose was reduced during his stay, so that they can then monitor him in case he does begin smoking again.

Case 2: A woman with constipation

A woman aged 40 years* presents at the pharmacy. The pharmacist recognises her as she often comes in to collect medicine for her family. They are aware that she has a history of schizophrenia and that she was started on clozapine three months ago. She receives this from her mental health team on a weekly basis.

She has visited the pharmacy to discuss constipation that she is experiencing. She has noticed that since she was started on clozapine, her bowel movements have become less frequent. She is concerned as she is currently only able to go to the toilet about once per week. She explains that she feels uncomfortable and sick, and although she has been trying to change her diet to include more fibre, it does not seem to be helping. The patient asks for advice on a suitable laxative.

What needs to be considered?

Constipation is a very common side effect of clozapine . However, it has the potential to become serious and, in rare cases, even fatal [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] . While minor constipation can be managed using over-the-counter medicines (e.g. stimulant laxatives, such as senna, are normally recommended first-line with stool softeners, such as docusate, or osmotic laxatives, such as lactulose, as an alternative choice), severe constipation should be checked by a doctor to ensure there is no serious bowel obstruction as this can lead to paralytic ileus, which can be fatal [9] . Symptoms indicative of severe constipation include: no improvement or bowel movement following laxative use, fever, stomach pain, vomiting, loss of appetite and/or diarrhoea, which can be a sign of faecal impaction overflow.

As the patient has been experiencing this for some time and is only opening her bowels once per week, as well as having other symptoms (i.e. feeling uncomfortable and sick), she should be advised to see her GP as soon as possible.

The patient returns to the pharmacy again a few weeks later to collect a prescription for a member of their family and thanks the pharmacist for their advice. The patient was prescribed a laxative that has led to resolution of symptoms and she explains that she is feeling much better. Although she has a repeat prescription for lactulose 15ml twice per day, she says she is not sure whether she needs to continue to take it as she feels better.

What advice should be provided?

As she has already had an episode of constipation, despite dietary changes, it would be best for the patient to continue with the lactulose at the same dose (i.e. 15ml twice daily), to prevent the problem occurring again. Explain to the patient that as constipation is a common side effect of clozapine, it is reasonable for her to take laxatives before she gets constipation to prevent complications.

Pharmacists should encourage any patient who has previously had constipation to continue taking prescribed laxatives and explain why this is important. Pharmacists should also continue to ask patients about their bowel habits to help pick up any constipation that may be returning. Where pharmacists identify patients who have had problems with constipation prior to starting clozapine, they can recommend the use of a prophylactic laxative such as lactulose.

Case 3: A mother is concerned for her son who is talking to someone who is not there

A woman has been visiting the pharmacy for the past 3 months to collect a prescription for her son, aged 17 years*. In the past, the patient has collected his own medicine. Today the patient has presented with his mother; he looks dishevelled, preoccupied and does not speak to anyone in the pharmacy.

His mother beckons you to the side and expresses her concern for her son, explaining that she often hears him talking to someone who is not there. She adds that he is spending a lot of time in his room by himself and has accused her of tampering with his things. She is not sure what she should do and asks for advice.

What action can the pharmacist take?

It is important to reassure the mother that there is help available to review her son and identify if there are any problems that he is experiencing, but explain it is difficult to say at this point what he may be experiencing. Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness which has several symptoms that are classified as positive (e.g. hallucinations and delusions), negative (e.g. social withdrawal, self-neglect) and cognitive (e.g. poor memory and attention).

Many patients who go on to be diagnosed with schizophrenia will experience a prodromal period before schizophrenia is diagnosed. This may be a period where negative symptoms dominate and patients may become isolated and withdrawn. These symptoms can be confused with depression, particularly in younger people, though depression and anxiety disorders themselves may be prominent and treatment for these may also be needed. In this case, the patient’s mother is describing potential psychotic symptoms and it would be best for her son to be assessed. She should be encouraged to take her son to the GP for an assessment; however, if she is unable to do so, she can talk to the GP herself. It is usually the role of the doctor to refer patients for an assessment and to ensure that any other medical problems are assessed.

Three months later, the patient comes into the pharmacy and seems to be much more like his usual self, having been started on an antipsychotic. He collects his prescription for risperidone and mentions that he is very worried about his weight, which has increased since he started taking the newly prescribed tablets. Although he does not keep track of his weight, he has noticed a physical change and that some of his clothes no longer fit him.

What advice can the pharmacist provide?

Weight gain is common with many antipsychotics [10] . Risperidone is usually associated with a moderate chance of weight gain, which can occur early on in treatment [6] , [11] , [12] . As such, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends weekly monitoring of weight initially [13] . As well as weight gain, risperidone can be associated with an increased risk of diabetes and dyslipidaemia, which must also be monitored [6] , [11] , [12] . For example, the lipid profile and glucose should be assessed at 12 weeks, 6 months and then annually [12] .

The pharmacist should encourage the patient to attend any appointments for monitoring, which may be provided by his GP or mental health team, and to speak to his mental health team about his weight gain. If he agrees, the pharmacist could inform the patient’s mental health team of his weight gain and concerns on his behalf. It is important to tackle weight gain early on in treatment, as weight loss can be difficult to achieve, even if the medicine is changed.

The pharmacist should provide the patient with advice on healthy eating (e.g. eating a balanced diet with at least five fruit and vegetables per day) and exercising regularly (e.g. doing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week), and direct him to locally available services. The pharmacist can record the adverse effect on the patient’s medical record, which will help flag this in the future and thus help other pharmacists to intervene should he be prescribed risperidone again.

*All case studies are fictional.

Useful resources

- Mind — Schizophrenia

- Rethink Mental Illness — Schizophrenia

- Mental Health Foundation — Schizophrenia

- Royal College of Psychiatrists — Schizophrenia

- NICE guidance [CG178] — Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management

- NICE guidance [CG155] — Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management

- British Association for Psychopharmacology — Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology

About the author

Nicola Greenhalgh is lead pharmacist, Mental Health Services, North East London NHS Foundation Trust

[1] Chiu CC, Lu ML, Huang MC & Chen KP. Heavy smoking, reduced olanzapine levels, and treatment effects: a case report. Ther Drug Monit 2004;26(5):579–581. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200410000-00018

[2] de Leon J. Psychopharmacology: atypical antipsychotic dosing: the effect of smoking and caffeine. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55(5):491–493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.491

[3] Mayerova M, Ustohal L, Jarkovsky J et al . Influence of dose, gender, and cigarette smoking on clozapine plasma concentrations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018;14:1535–1543. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S163839

[4] Ashir M & Petterson L. Smoking bans and clozapine levels. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2008;14(5):398–399. doi: 10.1192/apt.14.5.398b

[5] Young CR, Bowers MB & Mazure CM. Management of the adverse effects of clozapine. Schizophr Bull 1998;24(3):381–390. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033333

[6] Taylor D, Barnes TRE & Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry . 13th edn. London: Wiley Blackwell; 2018

[7] Oke V, Schmidt F, Bhattarai B et al . Unrecognized clozapine-related constipation leading to fatal intra-abdominal sepsis — a case report. Int Med Case Rep J 2015;8:189–192. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S86716

[8] Hibbard KR, Propst A, Frank DE & Wyse J. Fatalities associated with clozapine-related constipation and bowel obstruction: a literature review and two case reports. Psychosomatics 2009;50(4):416–419. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.416

[9] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Clozapine: reminder of potentially fatal risk of intestinal obstruction, faecal impaction, and paralytic ileus. 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/clozapine-reminder-of-potentially-fatal-risk-of-intestinal-obstruction-faecal-impaction-and-paralytic-ileus (accessed April 2020)

[10] Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382(9896):951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3

[11] Bazire S. Psychotropic Drug Directory . Norwich: Lloyd-Reinhold Communications LLP; 2018

[12] Cooper SJ & Reynolds GP. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol 2016;30(8):717–748. doi: 10.1177/0269881116645254

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 (accessed April 2020)

You might also be interested in…

Nearly half of long-term antidepressant users could safely taper off medication using helpline

Boots UK shuts online mental health service to new patients

Eating disorders: identification, treatment and support

- DOI: 10.7759/cureus.66306

- Corpus ID: 271753481

Caffeine-Induced Psychosis: A Case Report and Review of Literature

- Dylan Mannix , Kate Mulholland , Fintan Byrne

- Published in Cureus 6 August 2024

- Psychology, Medicine

20 References

Adenosine a2a and dopamine d2 receptor interaction controls fatigue resistance, psychosis following caffeine consumption in a young adolescent: review of case and literature, a method for tapering antipsychotic treatment that may minimize the risk of relapse, caffeine-induced psychosis and a review of statutory approaches to involuntary intoxication, the safety of ingested caffeine: a comprehensive review, psychopathology related to energy drinks: a psychosis case report, caffeine increases striatal dopamine d2/d3 receptor availability in the human brain, low-dose caffeine may exacerbate psychotic symptoms in people with schizophrenia., caffeine use disorder: a comprehensive review and research agenda., the neuroprotective effects of caffeine, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

The relationship between clinical and psychophysical assessments of visual perceptual disturbances in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: a preliminary study.

1. Introduction

2. materials and methods, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Yung, A.R.; McGorry, P.D.; McFarlane, C.A.; Jackson, H.J.; Patton, G.C.; Rakkar, A. Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 1996 , 22 , 283–303. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Schultze-Lutter, F.; Michel, C.; Schmidt, S.J.; Schimmelmann, B.G.; Maric, N.P.; Salokangas, R.K.; Riecher-Rossler, A.; van der Gaag, M.; Nordentoft, M.; Raballo, A.; et al. EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur. Psychiatry 2015 , 30 , 405–416. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]