- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The History Behind Tensions Between Israelis And Palestinians

The conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians is long and complex. NPR's Lulu Garcia-Navarro explains what has lead up to the latest attacks, and how it's different than before.

Copyright © 2021 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Back to Map

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Center for Preventive Action

Hamas launched its deadly attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, prompting the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) to engage in aerial campaigns and ground operations within the Gaza Strip. On June 8, the IDF undertook an operation in central Gaza to rescue four hostages while Gazan authorities reported that 274 Palestinians were killed, and hundreds of others were injured. Other efforts to free the more than one hundred remaining Israeli and foreign hostages taken by Hamas on October 7 have been largely unsuccessful, and their location and health status are unknown. Almost two million Gazans—more than 85 percent of the population—have fled their homes since October 2023. Recent casualty estimates from the Hamas-run Gazan Health Ministry place the death toll in Gaza at around 40,000, though such numbers are challenging to verify due to limited international access to the strip. On July 13, Israel conducted a major strike on south Gaza, targeting two top Hamas commanders that killed at least seventy-one people. Meanwhile, neither Hamas nor Israel have agreed to the terms laid out by U.S. President Joe Biden for a ceasefire and hostage release.

The conflict has sparked increased regional tensions across the Middle East. Hezbollah fighters in Lebanon have engaged in cross-border skirmishes with the IDF, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have shot missiles at Israel and commercial ships in the Red Sea, and other Iran-backed groups have launched dozens of attacks on U.S. military positions in Iraq and Syria. (For more on the direct confrontation between Iran and Israel and the role of the United States, visit the “ Confrontation with Iran ” page. For more on the direct confrontation between Hezbollah and Israel, visit the “ Instability in Lebanon ” page.)

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dates back to the end of the nineteenth century. In 1947, the United Nations adopted Resolution 181 , known as the Partition Plan, which sought to divide the British Mandate of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states. On May 14, 1948, the State of Israel was created, sparking the first Arab-Israeli War. The war ended in 1949 with Israel’s victory, but 750,000 Palestinians were displaced, and the territory was divided into 3 parts: the State of Israel, the West Bank (of the Jordan River), and the Gaza Strip.

Over the following years, tensions rose in the region, particularly between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Following the 1956 Suez Crisis and Israel’s invasion of the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt, Jordan, and Syria signed mutual defense pacts in anticipation of a possible mobilization of Israeli troops. In June 1967, following a series of maneuvers by Egyptian President Abdel Gamal Nasser, Israel preemptively attacked Egyptian and Syrian air forces, starting the Six-Day War. After the war, Israel gained territorial control over the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt; the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan; and the Golan Heights from Syria.

Six years later, in what is referred to as the Yom Kippur War or the October War, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise two-front attack on Israel to regain their lost territory; the conflict did not result in significant gains for Egypt, Israel, or Syria, but Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat declared the war a victory for Egypt as it allowed Egypt and Syria to negotiate over previously ceded territory . Finally, in 1979, following a series of cease-fires and peace negotiations, representatives from Egypt and Israel signed the Camp David Accords , a peace treaty that ended the thirty-year conflict between Egypt and Israel.

Even though the Camp David Accords improved relations between Israel and its neighbors, the question of Palestinian self-determination and self-governance remained unresolved. In 1987, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip rose up against the Israeli government in what is known as the first intifada. The 1993 Oslo I Accords mediated the conflict, setting up a framework for the Palestinians to govern themselves in the West Bank and Gaza, and enabled mutual recognition between the newly established Palestinian Authority and Israel’s government. In 1995, the Oslo II Accords expanded on the first agreement, adding provisions that mandated the complete withdrawal of Israel from 6 cities and 450 towns in the West Bank.

In 2000, sparked in part by Palestinian grievances over Israel’s control over the West Bank, a stagnating peace process, and former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s visit to the al-Aqsa mosque—the third holiest site in Islam—in September 2000, Palestinians launched the second intifada, which would last until 2005. In response, the Israeli government approved the construction of a barrier wall around the West Bank in 2002, despite opposition from the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court.

Factionalism among the Palestinians flared up when Hamas won the Palestinian Authority’s parliamentary elections in 2006, deposing longtime majority party Fatah. This gave Hamas, a political and militant movement inspired by the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood, control of the Gaza Strip. Gaza is a small piece of land on the Mediterranean Sea that borders Egypt to the south and has been under the rule of the semi-autonomous Palestinian Authority since 1993. The United States and European Union, among others, did not acknowledge Hamas’ electoral victory, as the group has been considered a terrorist organization by western governments since the late 1990s. Following Hamas’ seizure of control, violence broke out between Hamas and Fatah. Between 2006 and 2011, a series of failed peace talks and deadly confrontations culminated in an agreement to reconcile. Fatah entered into a unity government with Hamas in 2014.

In the summer of 2014, clashes in the Palestinian territories precipitated a military confrontation between the Israeli military and Hamas in which Hamas fired nearly three thousand rockets at Israel, and Israel retaliated with a major offensive in Gaza. The skirmish ended in late August 2014 with a cease-fire deal brokered by Egypt, but only after 73 Israelis and 2,251 Palestinians were killed . After a wave of violence between Israelis and Palestinians in 2015, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas of Fatah announced that Palestinians would no longer be bound by the territorial divisions created by the Oslo Accords .

In March of 2018, Israeli troops killed 183 Palestinians and wounded 6,000 others after some Palestinians stormed the perimeter fence between the Gaza Strip and Israel and threw rocks during an otherwise peaceful demonstration. Just months later, Hamas militants fired over one hundred rockets into Israel, and Israel responded with strikes on more than fifty targets in Gaza during a twenty-four-hour flare-up. The tense political atmosphere resulted in a return to disunity between Fatah and Hamas, with Mahmoud Abbas’ Fatah party controlling the Palestinian Authority from the West Bank and Hamas de facto ruling the Gaza Strip.

The Donald J. Trump administration reversed longstanding U.S. policy by canceling funding for the UN Relief and Works Agency, which provides aid to Palestinian refugees, and relocating the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. The Trump administration also helped broker the Abraham Accords , under which Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates normalized relations with Israel, becoming only the third and fourth countries in the region—following Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994—to do so. Similar deals followed with Morocco [PDF] and Sudan . Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas of Fatah rejected the accords, as did Hamas .

In early May 2021, after a court ruled in favor of the eviction of several Palestinian families from East Jerusalem properties, protests erupted, with Israeli police employing force against demonstrators. After several consecutive days of violence, Hamas, the militant group which governs Gaza, and other Palestinian militant groups launched hundreds of rockets into Israeli territory. Israel responded with artillery bombardments and airstrikes, killing more than twenty Palestinians and hitting both military and non-military infrastructure, including residential buildings, media headquarters , and refugee and healthcare facilities . After eleven days, Israel and Hamas agreed to a cease-fire , with both sides claiming victory. The fighting killed more than 250 Palestinians and at least 13 Israelis, wounded nearly 2,000 others, and displaced 72,000 Palestinians.

The most far-right and religious government in Israel’s history, led by Benjamin ‘Bibi’ Netanyahu and his Likud party and comprising two ultra-Orthodox parties and three far-right parties, was inaugurated in late December 2022. The coalition government prioritized the expansion and development of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, endorsed discrimination against LGBTQ+ people on religious grounds, and voted to limit judicial oversight of the government in May 2023 after a delay due to nationwide protests in March.

Following the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas on October 7, 2023, President Joe Biden made a strong statement of support for Israel. On the same day that Israel declared war against Hamas, the United States announced that it would send renewed shipments of arms and move its Mediterranean Sea warships closer to Israel. While the UN Security Council called an emergency meeting to discuss the renewed violence, the members failed to come to a consensus statement. Given the history of brutality when Israel and Palestinian extremist groups have fought in the past, international groups quickly expressed concern for the safety of civilians in Israel and the Palestinian territories as well as those being held hostage by militants in Gaza. In the first month of fighting, approximately 1,300 Israelis and 10,000 Palestinians were killed. Increasing loss of life is of primary concern in the conflict.

While the United States said there was “no direct evidence” that Iranian intelligence and security forces directly helped Hamas plan its October 7 attack, Iran has a well-established patronage relationship with Hamas and other extremist groups across the Middle East. Israel has exchanged artillery fire with Iran-backed Hezbollah almost daily and struck Syrian military targets and airports, prompting concern that the war could expand north. To the south, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have launched multiple rounds of missiles at Israel as well. Meanwhile, the Islamic Resistance of Iraq, a coalition of Iranian-backed militias, has claimed responsibility for dozens of attacks on U.S. military targets in Iraq and Syria since the war began.

A 2023 effort by the United States to help broker a normalization accord between Israel and Saudi Arabia was thrown into chaos by the October conflict. Saudi Arabia has long advocated for the rights and safety of Palestinian Arab populations in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. Especially in Gaza, those populations are now in the path of IDF operations, jeopardizing the progress the Israelis and Saudis made toward a common understanding. However, the United States says the Saudis have indicated they are still interested in the deal.

In early October 2023, Hamas fighters fired rockets into Israel and stormed southern Israeli cities and towns across the border of the Gaza Strip, killing more than 1,300 Israelis, injuring 3,300, and taking hundreds of hostages. The attack took Israel by surprise, though the state quickly mounted a deadly retaliatory operation. One day after the October 7 attack, the Israeli cabinet formally declared war against Hamas, followed by a directive from the defense minister to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) to carry out a “complete siege” of Gaza. It is the most significant escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in several decades.

Israel ordered more than one million Palestinian civilians in northern Gaza to evacuate ahead of a ground invasion that began on October 27th. The ground invasion began in the north in conjunction with Israel’s continued aerial assault. The first stage of the ground invasion ended on November 24 with the hostage-for-prisoner swap that also allowed more aid into Gaza. After seven days, the war resumed—particularly in Khan Younis , the largest city in southern Gaza that Israel claims is a Hamas stronghold.

Under pressure from its principal ally, the United States, Israel announced it would begin to withdraw soldiers from the Gaza Strip in January 2024. Since then, military analysts speculate that the IDF has pulled out at least 90 percent of the troops that were in the territory a few months ago, leaving one remaining brigade. Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, however, is unwavering in his position that an Israeli offensive in Rafah, the southernmost city in the Gaza Strip where over one million Palestinians have taken refuge, is essential to eradicating Hamas.

In mid-March, Israel conducted a two-week raid on al-Shifa Hospital, the largest medical center in Gaza. Israel claimed Hamas was operating out of al-Shifa, and it reportedly killed 200 fighters and captured an additional 500. The U.S. intelligence community later determined that Hamas had used al-Shifa as a command center and held some hostages there, but the Islamist group evacuated the complex days prior to the Israeli operation. In late April, two mass graves were discovered at al-Shifa and Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis, another target of an Israeli operation. More than 300 bodies were found among the two sites; the United Nations has called for an independent investigation.

On April 1, Israel launched an airstrike on an Iranian consular building in Damascus, Syria, killing multiple senior Iranian military officers. In response, Iran engaged directly in the war by launching over 300 drones and missiles at Israel on April 13. Though Israel was able to ward off the attack and only sustained minor damage to an air base, the escalation marked Iran’s first-ever direct attack on Israel. As Israel weighed an extensive counterstrike on multiple military targets in Iran, the United States and other allies advised against actions that they feared would further widen the war. Israel ultimately launched a more limited aerial strike on military bases in Isfahan and Tabriz on April 19. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi later downplayed the response, suggesting Iran aimed to avoid further escalation.

Gaza is desperately low on water, fuel, and supplies as Hamas has rejected the most recent cease-fire proposals mediated by the United States and Egypt, while Israel has limited the amount of aid that can enter. Many humanitarian agencies suspended their operations after Israel killed seven World Center Kitchen employees in an airstrike. The World Food Programme warns famine is now imminent in Gaza. Only eleven out of thirty-five hospitals in the strip remain partially functional due to attacks on medical infrastructure and a lack of basic supplies. The World Health Organization has warned of disease spread in addition to mounting civilian casualties.

The displacement of millions more Palestinians presents a challenge for Egypt and Jordan, which have absorbed hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in the past but have resisted accepting anyone during the current war. They fear that Gazans, many of whom were already displaced from elsewhere in Israel, will not be allowed to return once they leave. Egypt also fears that Hamas fighters could enter Egypt and trigger a new war in the Sinai by launching attacks on Israel or destabilizing the authoritarian regime of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi by supporting the Muslim Brotherhood. So far, negotiations have resulted in only 1,100 people exiting Gaza through the Rafah border crossing to Egypt. The other 1.5 million displaced Gazans—70 percent of the territory’s population—remained confined to southern Gaza and face increasingly dire living conditions and security risks.

Latest News

Sign up for our newsletter, receive the center for preventive action's quarterly snapshot of global hot spots with expert analysis on ways to prevent and mitigate deadly conflict..

Home — Essay Samples — War — Israeli Palestinian Conflict — Israel-Palestine Conflict: Historical Context, Causes, and Resolution

Israel-palestine Conflict: Historical Context, Causes, and Resolution

- Categories: Israeli Palestinian Conflict

About this sample

Words: 612 |

Published: Jan 31, 2024

Words: 612 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical context, causes of the conflict, major parties involved, international involvement, consequences and impacts, attempts at resolution, current situation and future prospects.

- United Nations. "Israel-Palestine Conflict: An Overview." https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/israel-palestine-conflict/

- BBC News. "Israel and Palestinians: The Conflict Explained." https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-43789452

- Council on Foreign Relations. "The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict." https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/israeli-palestinian-conflict

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: War

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1038 words

2 pages / 1074 words

3 pages / 1286 words

4 pages / 1788 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Israeli Palestinian Conflict

Conflict between Israel and Palestine has far-reaching implications, not only for the region but also for the global economy and politics. Possible scenarios of how the conflict might shape global economic and political [...]

One of the most powerful ways to understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is through personal narratives. These stories provide a window into the everyday lives of individuals on both sides who are affected by the ongoing [...]

Rooted in historical, religious, and territorial grievances, the conflict has drawn the attention of numerous global actors, each attempting to influence its resolution. This essay delves into the multifaceted roles played by [...]

The conflict between Israel and Palestine has persisted for decades, marked by cycles of violence, failed negotiations, and deep-rooted animosities. As the world entered 2023, the prospects for peace remained uncertain amidst [...]

The Israeli and Palestine conflict is an ongoing crisis between Muslims and Jews. There have been various attempts made to resolve the conflict, but the Israelis and Palestinians have failed to solve a final peace arrangement. [...]

The political aspect and amount of acknowledgment of human rights of any country or part of the world is a crucial facet when considering violence, environmental issues, economic issues, education, and much more. The middle east [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Civil Society

- Constitutions

- Freedom of Expression

- Gulf Countries

- Human Rights

- Islamist Politics

- Palestinians

- Parliaments

- Political Parties

- Political Reform

- Religious Freedom

- Saudi Arabia

- United Arab Emirates

- Women & Gender

- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Religion and the Israel-Palestinian Conflict: Cause, Consequence, and Cure

Mohamed Galal Mostafa is a former Egyptian diplomat, and currently a researcher at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is driven by several factors: ethnic, national, historical, and religious. This brief essay focuses on the religious dimension of the conflict, which both historical and recent events suggest lies at its core. That much is almost a truism. What is less often appreciated, however, is how much religion impacts the identity of actors implicated in this conflict, the practical issues at stake, and the relevant policies and attitudes -- even of non-religious participants on both sides. It follows that religion must also be part of any real solution to this tragic and protracted conflict, in ways a concluding paragraph will very briefly outline.

Why is religion at the core of this conflict?

Several religious factors pertinent to Islam and Judaism dictate the role of religion as the main factor in the conflict, notably including the sanctity of holy sites and the apocalyptic narratives of both religions, which are detrimental to any potential for lasting peace between the two sides. Extreme religious Zionists in Israel increasingly see themselves as guardians and definers of the how the Jewish state should be, and are very stringent when it comes to any concessions to the Arabs. On the other hand, Islamist groups in Palestine and elsewhere in the Islamic world advocate the necessity of liberating the “holy” territories and sites for religious reasons, and preach violence and hatred against Israel and the Jewish people.

Religion-based rumors propagated by extremists in the media and social media about the hidden religious agendas of the other side exacerbate these tensions. Examples include rumors about a “Jewish Plan” to destroy al Aqsa mosque and build the Jewish third temple on its remnants, and, on the other side rumors that Muslims hold the annihilation of Jews at the core of their belief.

In addition, worsening socio-economic conditions in the Arab and Islamic world contribute to the growth of religious radicalism, pushing a larger percentage of youth towards fanaticism, and religion-inspired politics.

The advent of the Arab spring, ironically, also posed a threat to Arab-Israeli peace, as previously stable regimes were often challenged by extreme political views. A prominent example was the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, who after succeeding to the presidency in 2012, threatened to compromise the peace agreement with Israel based on their religious ideology – even if they did not immediately tear up the treaty.

Practical Consequences O n Negotiations

If we take a closer look at the permanent status issues – borders, security, mutual recognition, refugees, the Jewish settlements in the West Bank, and the issue of authority over Jerusalem -- we find that the last two are directly linked to the faiths of Jewish people and Muslim people around the world. The original ownership and authority over Jerusalem are highly contested due to the presence of holy sites for Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the city. This conflict is also deeply rooted in history, in which Jerusalem has been attacked fifty-two times, captured and recaptured forty-four times, besieged twenty-three times, and destroyed twice. The city was ruled by the Ancient Egyptians, the Canaanites, the Israelites, the Greeks, the Romans, the Persians, Byzantines, the Islamic Caliphates, the Crusaders, the Ottomans, and finally the British, before its division into Israeli and Jordanian sectors from 1948 to 1967.

In Jewish and Biblical history, Jerusalem was the capital of the Kingdom of Israel during the reign of King David. It is also home to the Temple Mount, and the Western Wall, both highly sanctified sites in Judaism. In Islamic history, the city was the first Muslim Qiblah (the direction which Muslims face during their prayer). It is also the place where Prophet Muhammad’s Isra’ and Mi'raj (bringing forward and ascension to heaven, also called the night journey) ensued according to the Qur’an.

Thus the sanctity of Jerusalem resonates among many Muslims around the world, not just Palestinians. Reactions in the Arab and the Islamic world to the recent violence in Gaza and the West Bank after the U.S. decision to relocate the embassy to Jerusalem suggest that many view this issue mainly in a religious light. The narratives on social media platforms and the media in general in those countries usually included references to religion, even among seemingly secular people.

The issue of West Bank settlements, too, has a religious aspect. It concerns the physical restoration of the biblical land of Israel before the return of the Messiah, something central to the beliefs of some orthodox Jews. They continue to settle the West Bank to fulfill this prophecy, clashing with the local Palestinians.

On the other hand, according to fundamentalist schools of Islam, at the end of days, the whole land of Israel and Palestine should be under Islamic rule. Prophecies surrounding this issue are deeply rooted in some versions of the Hadith (traditional sayings of the Prophet), although only implied in the Qur’an.

Historical and Organizational Consequences

As far back as the 1948 war, some Jewish extremist groups justified their contribution to the conflict as part of a divinely promised return to the holy land of Israel. More recently, however, the most extreme such groups, like the “Gush Emunim Underground” which plotted to bomb the mosques in the Temple Mount area back in the 1980s, have been banned by the Israeli authorities

On the other side, several religious extremist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood justified their contribution to the conflict in 1948 as an eschatological event pertinent to the approach of the Day of Judgment. Nowadays, terrorist Brotherhood offshoots like Hamas call for using violence against Israel in the name of Islam, without distinction between civilian and military targets. They continue to use religion to gain supporters in Gaza and elsewhere by propagating this apocalyptic narrative. This Muslim Brotherhood group ideology, stretching through many Arab (and several non-Arab) countries, seeks to revive Islam and re-establish the historical Islamic Caliphate by seizing power. They consider Israel to be a “foreign object” in the continuum of a potential Islamic Caliphate, and they continue to call for the use of violence against it.

In parallel to this extreme Sunni side, ever since the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979, Iran has been the fiercest in opposing Israel. Its radical regime calls openly for the destruction of Israel and asserts the necessity of this quest from a theological standpoint. It finances Hezbollah and Hamas and supplies them with weapons and training, as well as supporting Assad’s forces in Syria, thereby posing a direct security threat to Israel – all allegedly in the name of Islam.

Social Consequences

For two Arab countries, Egypt and Jordan, direct peacemaking was achieved with Israel. Nevertheless, that did not entail the people-to-people or cultural normalization that is assumed to accompany peace, due to many reasons -- including religious ones. Accepting peace with Israel may be viewed as religious treachery, which goes against the beliefs not only of extremists but also of many relative moderates in Arab states. The key point is that these various forms of religion-based conflict drivers are not limited to religious groups, but are linked to much wider bases in society. This results from two major factors, as follows:

Interest and Identity Overlap: Interests of religious extremists who are directly linked to the religious drivers at many instances overlap with other segments in the Arab and Islamic societies. They share some elements of their identities, if not the whole. For example, a secular nationalist Palestinian and an extremely religious, Salafi Palestinian in the Qassam Brigades of Hamas may share very similar views of Israel. Much the same is true of some secularists, traditionalists, and fundamentalists in other Arab or Islamic societies.

Systematic Abuse of Linkages to Wider Bases in Societies: Religious extremists in the Arab and Islamic world and in Israel, whether violent or not, have used deliberately the ideological and functional linkages to connect to wider bases in their respective countries. Ideologically, links with the wider society are established by trying to radicalize elements that have this potential, either due to natural tendencies toward perceived communal self-defense, or to the superficial knowledge of their religions. For example, extremists would use an isolated incident of violence against the Jewish community to justify retaliation by their wider society. A non-religious traditional Arab might well share the fear of secularization, and of “Jewish influence,” with the Islamist. Functionally, extreme Imams have very strong tools at their disposals across the Arab and Islamic world to promote violence through their mosques and privately funded media, subjecting people repeatedly to the narrative and rhetoric of violence against Israel in particular and Jewish people in general.

Possible Interventions

To contribute to curbing the religious violence in this conflict, several interventions can be considered: interfaith dialogue; the remembrance of past fruitful cooperation between Jews and Muslims, ever since the seventh century; and focusing on religious texts asserting positive and tolerant religious values, and reinforcing these values in educational systems on both sides. These are perhaps not new ideas. What should be new, however, is the urgency and centrality of this religious component as part of any current effort to achieve an Israeli-Palestinian “deal of the century” – or even just to mitigate the conflict and pave the way for peaceful coexistence in the long-term future.

Recommended

- Frzand Sherko

- Sabina Henneberg

- Neomi Neumann

Stay up to date

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Timeline

Explore the history and important events behind the long-standing Middle East conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians from 1947 to today.

Smoke rises in Gaza following Israeli strikes on October 9, 2023.

Source: Mohammed Salem / Reuters

The conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians reflects a long-standing struggle in the region encompassing the land between the Jordan River to the east and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. That conflict has deep historical roots, shaped by statehood claims from the Israelis and the Palestinians that have been supported by various international agendas and activities over time.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dates back more than a century, with flashpoints building from the United Nations’ 1947 initial UN Partition Plan to the 1973 Yom Kippur War, to the recent Israel-Hamas war sparked in October 2023.

Despite continued efforts at brokering peace—including the 1979 Camp David Accords, the Oslo Accords of the 1990s, and the 2020 Abraham Accords—conflict has persisted.

This timeline explores some of the pivotal moments in the conflict from 1947 to today.

Universal History Archive

The UN General Assembly passes Resolution 181 calling for the partition of the Palestinian territories into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. The resolution also envisions an international, UN-run body to administer Jerusalem. The Palestinian territories had been under the military and administrative control of the United Kingdom (known as a mandate) since the 1917 defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Civil strife and violence between the Jewish and Arab communities of the Palestinian territories intensifies.

Saar Yaacov/Israel GPO

Israel declares its independence as the British rule ends. Sparked by Israel’s declaration of independence, the first Arab-Israeli War begins. Egypt (supported by Saudi Arabian, Sudanese, and Yemeni troops), Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria invade Israel. The fighting continues until 1949, when Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria sign armistice agreements.

Bettmann / Getty Images

Over the course of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, at least seven hundred thousand Palestinian refugees flee their homes in an exodus known to Palestinians as the nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”). Israel wins the war, retaining the territory provided to it by the United Nations and capturing some of the areas designated for the imagined future Palestinian state. Israel gains control of West Jerusalem, Egypt gains the Gaza Strip, and Jordan gains the West Bank and East Jerusalem, including the Old City and its historic Jewish quarter. In 1948, the UN General Assembly passes Resolution 194, which calls for the repatriation of Palestinian refugees . The Palestinians will later point to Resolution 194 as having established a “right of return” for Palestinian refugees and their descendants. The specific parameters of that return are debated in the decades that follow, including among many descendants from the 1948 refugees and the three hundred thousand Palestinians who will flee their homes during the June 1967 war.

Israel GPO.

Israel and several of its Arab neighbors fight the Six-Day War. Israel wins a decisive victory: it suffers seven hundred casualties; its adversaries suffer nearly twenty thousand. Israel emerges with control of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—areas inhabited primarily by Palestinians—as well as all of East Jerusalem. Israel also takes control of Syria’s Golan Heights and the Sinai Peninsula, which is part of Egypt. Israel will stay in the Sinai Peninsula until April 1982.

Yutaka Nagata / United Nations

The UN Security Council passes Resolution 242 calling for Israeli “withdrawal … from territories occupied in the recent conflict” and for the termination of “states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgement of the sovereignty , territorial integrity, and political independence of every state in the area and the right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries.” The resolution establishes the concept of land for peace .

Another Arab-Israeli war, known variously as the Yom Kippur War, the Ramadan War, and the October War, is fought when Egypt and Syria attempt to retake the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights. Cold War tensions spike as the Soviet Union aids Egypt and Syria and the United States aids Israel. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries begins an oil embargo on countries that support Israel, and the price of oil skyrockets. The fighting ends after a UN-sponsored cease-fire (negotiated by the United States and the Soviet Union) takes hold. The UN Security Council passes Resolution 338, which calls for implementing UN Security Council Resolution 242.

Warren K. Leffler / Library of Congress.

Israel and Egypt sign the Camp David Accords, which establish a basis for a peace treaty between the two countries. The accords also commit the Israeli and Egyptian governments, along with other parties, to negotiate the disposition of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

François Lochon / Getty Images

Egypt and Israel sign a peace treaty, the first between Israel and one of its Arab neighbors. The treaty commits Israel to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and evacuate its settlements there. The termination of the state of war between Egypt and Israel leads to the normalization of diplomatic and commercial relations between the two countries. Israel’s prime minister and Egypt’s president exchange letters reaffirming their commitment—outlined in the Camp David Accords—to negotiate the disposition of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Jim Hollander / Reuters

An Israeli driver kills four Palestinians in a car accident that sparks the first intifada, or uprising, against Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. The image of Palestinians throwing rocks at Israeli tanks becomes the enduring image of the intifada. Over the next six years, roughly 200 Israelis and 1,300 Palestinians are killed.

A Palestinian cleric named Sheikh Ahmed Yassin establishes the militant group Hamas as an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas endorses jihad as a way to regain territory for Muslims; the United States designates Hamas a foreign terrorist organization in 1997.

Ali Jareki / Reuters

King Hussein of Jordan relinquishes his country’s claims to the West Bank and East Jerusalem in favor of the claims of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In December of the same year, PLO Chairman Yasir Arafat denounces violence, recognizes Israel’s right to exist, and acknowledges UN Security Council Resolution 242 and the concept of land for peace. The United States responds to Arafat’s announcement by beginning direct talks with him, though it suspends the talks following a Palestinian terrorist attack against Israel.

David Valdez / U.S. National Archives

The Madrid Peace Conference begins, sponsored jointly by the United States and the Soviet Union . Israeli, Jordanian, Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian delegates attend the first negotiations among those parties. The talks proceed along bilateral tracks between Israel and its neighbors, though the Lebanese join the Syrian delegation and the Jordanian team includes Palestinian representatives. A multilateral track includes the wider Arab world and addresses regional issues. The talks last for two years without any breakthroughs.

Saar Yaacov / Israel GPO.

Secret negotiations in Norway result in the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, also known as the Oslo Accords. Before the accords are signed, Israel and the PLO recognize each other in an exchange of letters. Israel and the PLO agree to the creation of the Palestinian Authority to temporarily administer the Gaza Strip and West Bank. Israel also agrees to begin withdrawing from parts of the West Bank, though large swaths of land and Israeli settlements remain under the Israeli military’s exclusive control. The Oslo Accords envision a peace agreement by 1999. Palestinian leader Arafat, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 for their efforts on the Oslo Accords.

Patrick Baz / AFP / Getty Images

The Israelis and the Palestinians sign the Gaza-Jericho Agreement, which begins implementation of the Oslo Accords. The agreement provides for an Israeli military withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho, a town in the West Bank, and for a transfer of authority from Israeli administration to the newly formed Palestinian Authority. The agreement also establishes the structure and composition of the Palestinian Authority, its jurisdiction and legislative powers, a Palestinian police force, and relations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Arafat returns to the Gaza Strip after a long absence.

Sa'ar Ya'acov / Israel Government Press Office Photo

Israel and Jordan sign a peace treaty, settling their territorial dispute and agreeing to future cooperation in sectors such as trade and tourism. This is Israel’s second peace treaty with an Arab state. It accords special administrative responsibilities for Jerusalem’s Muslim holy places to Jordan.

Israeli and Palestinian negotiators sign the Interim Agreement, sometimes called Oslo II. It gives the Palestinians control over additional areas of the West Bank and defines the security, electoral, public administration, and economic arrangements that will govern those areas until a final peace agreement is reached in 1999.

President Bill Clinton hosts Israeli and Palestinian leaders for talks at Camp David. Reports indicate that Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak is prepared to accept, among other things, Palestinian sovereignty over some 91 percent of the West Bank and certain parts of Jerusalem. The deal would include a land swap in which some Israeli land would go to the Palestinians in compensation for the remaining 9 percent of the West Bank, which would go to Israel. Two weeks of intensive discussion, however, fails to produce an agreement. President Clinton blames Arafat for the failure. Before leaving office several months later, Clinton lays out proposals for both sides. Talks between them continue, but without success.

Natalie Behring / Reuters

Israeli politicians, including Ariel Sharon, a controversial retired Israeli general, visit the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. The Palestinians view the visit as an effort to change the status quo at the holy site. The ensuing demonstrations turn violent, marking the beginning of a second intifada. It will last until 2005 and be markedly more violent than the first intifada. Four thousand Palestinians and one thousand Israelis die.

Nir Elias / Reuters

A terrorist attack kills thirty people at a Passover celebration at a hotel in the Israeli city of Netanya. As a result, the Israeli military reoccupies portions of the West Bank, including the city of Ramallah, where the Palestinian Authority is located and where Arafat has his West Bank headquarters.

Israel begins building a security barrier in the West Bank to protect Israeli cities and towns from terrorist attacks. The barrier, which is a wall in some stretches and a fence in others, is controversial because in places it cuts deep into West Bank territory to protect settlements. The Palestinians are cut off from Jerusalem, some Palestinian villages are sliced in half, and some Palestinians are unable to get to work or school as a result of the security barrier’s path. Israel’s Supreme Court forces changes in the barrier’s route, but the barrier continues to impede Palestinian movement and commerce in certain areas.

Ali Jarekji / Reuters

The Quartet, an informal group created to pursue Middle East peace comprising the United States, Russia, the United Nations, and the European Union , puts forth a Road Map for Peace based on the outline President George W. Bush offered in his 2002 speech. The road map lays out a plan for peace based on Palestinian reforms and a cessation of terrorism in return for an end to Israeli settlements and a new Palestinian state.

Paul Hanna / Reuters

Israel begins a unilateral withdrawal of settlers and military forces from the Gaza Strip. The Israeli military remains in control of Gaza’s borders (except the Gaza-Egypt border, which is controlled by Egypt), airspace, and coastline. After Israel’s withdrawal, Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad , and other smaller militant groups fire rockets from Gaza into southern Israel.

Ahmed Jadallah / Reuters

Hamas defeats Fatah, a Palestinian political faction founded in 1950s which was a long-dominant faction within the PLO, in Palestinian elections. The United States and other countries suspend their aid to the Palestinian Authority because they consider Hamas to be a terrorist organization. Fatah and Hamas make a deal to govern the West Bank and Gaza Strip together. The deal quickly fails, and Hamas takes over the Gaza Strip in 2007.

Ronen Zvulun / Reuters

Hamas operatives kidnap an Israeli soldier named Gilad Shalit on Israeli soil near the Gaza Strip. The Israeli military tries and fails to free him. He is held captive in Gaza until Israel—with the help of Egypt and the United States—negotiates his release in 2012.

Ammar Awad / Reuters

Israel attacks the Gaza Strip following nearly eight hundred rocket attacks from Gaza on Israeli towns in the months of November and December. The war lasts less than a month but kills hundreds of civilians, in addition to hundreds of combatants, and sparks international criticism.

Jonathan Ernst / Reuters

Secretary of State John Kerry seeks to restart final status negotiations. The process begins with the Israeli’s agreement to release 104 Palestinian prisoners and the Palestinians’ agreement not to use their new observer state status at the United Nations to advance the cause of statehood. Negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority collapsed in April 2014 over such issues as Israeli settlement growth, the status of a final round of prisoners, and Palestinian attempts to join several international organizations.

Suhaib Salem / Reuters

The PLO and Hamas sign an agreement to form a unity government. Tensions between the factions remain, however, and no unity government is formed. Gaza and the West Bank remain disconnected and under the control of rival Palestinian leaderships.

Baz Ratner / Reuters

After tit-for-tat attacks on Israeli and Palestinian civilians by extremists on both sides, Israel invades the Gaza Strip. The operation, code-named Protective Edge, lasts for fifty days, killing about two thousand Gazans, sixty-six Israeli soldiers, and five Israeli civilians. Unlike the conflicts from 2008 to 2009 and in 2012, Palestinian rocket fire targets major Israeli cities. The war ends after the United States, in consultation with Egypt, Israel, and other regional powers, brokers a cease-fire .

Muhammad Hamed / Reuters

Changing long-standing U.S. policy, U.S. President Donald Trump formally recognizes Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. He also pledges to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to that city, though the move is not set to occur immediately. Numerous foreign leaders, including those of Egypt, France, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, along with UN Secretary-General António Guterres, criticize the policy change. It also sparks protests and violence throughout East Jerusalem, Gaza, and the West Bank, as well as in Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and Jordan. In January 2018, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas declines to meet with U.S. Vice President Mike Pence during Pence’s trip to the region.

Carlos Barria / Reuters

The Trump administration recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, which Israel had formally annexed from Syria in 1981. The United States is the first country other than Israel to recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the territory.

Trump unveils his administration’s proposed Israeli-Palestinian peace plan, crafted by U.S. and Israeli diplomats without Palestinian input. The plan calls for a two-state solution with significant economic aid to the Palestinians. Many analysts criticize the plan as being one sided, stipulating impossible requirements for Palestinian statehood and paving the way for Israeli annexation of the West Bank. Palestinian authorities reject the plan immediately. Following the plan’s announcement, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announces Israel’s plan to annex portions of the West Bank as outlined in Trump’s proposal.

Tom Brenner / Reuters

Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates agree to normalize diplomatic relations with Israel, becoming the first Arab countries to do so in over twenty-five years. In return, Israel announces the suspension of its plans to annex territory in the West Bank. Morocco and Sudan subsequently also sign on to the agreement and normalize relations with Israel.

Evictions of Palestinians in East Jerusalem and clashes at al-Aqsa Mosque spark conflict between Israel and Hamas. Over two hundred people in Gaza and at least ten in Israel die. The Joe Biden administration helps mediate a truce and restores some U.S. aid and diplomatic contact with the Palestinians.

Israel launches a counterterrorism operation in the West Bank in response to attacks by Palestinians against Jewish Israelis. The operation and resulting resurgence contribute to the deadliest year for both sides since 2005, an uptick in violence that only turned out to rise in 2023.

Mohammed Salem / Reuters

Hamas launches an unprecedented surprise attack on Israel, leading to an explosion of violence. According to the Israeli government, the attack kills approximately 1,200 people, many of them civilians. Over 200 people are also taken hostage. The attack is the deadliest in Israel’s history. Hamas military leaders justify the attack by citing Israel’s long-running blockade on Gaza and its occupation of Palestinian lands. Following the attack, Israel launches a deadly counter offensive aiming to eradicate Hamas in Gaza. International bodies, including the International Criminal Court and International Court of Justice, have since issued investigations into Israeli and Hamas officials for violating international law . Both parties reject these claims. Despite a growing humanitarian crisis, as well as numerous attempts to broker ceasefire deals, the warring parties remain in conflict. As of July 2024, over 35,000 Palestinians have been killed, many of them civilians. Over 100 Israeli hostages are still held by Hamas.

What’s the Israel-Palestine conflict about? A simple guide

It’s killed tens of thousands of people and displaced millions. And its future lies in its past. We break it down.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has claimed tens of thousands of lives and displaced many millions of people and has its roots in a colonial act carried out more than a century ago.

With Israel declaring war on the Gaza Strip after an unprecedented attack by the armed Palestinian group Hamas on Saturday, the world’s eyes are again sharply focused on what might come next.

Keep reading

From hubris to humiliation: the 10 hours that shocked israel, fears of a ground invasion of gaza grow as israel vows ‘mighty vengeance’, ‘my voice is our lifeline’: gaza journalist and family amid israel bombing.

Hamas fighters have killed more than 800 Israelis in assaults on multiple towns in southern Israel. In response, Israel has launched a bombing campaign in the Gaza Strip, killing more than 500 Palestinians. It has mobilised troops along the Gaza border, apparently in preparation for a ground attack. And on Monday, it announced a “total blockade” of the Gaza Strip, stopping the supply of food, fuel and other essential commodities to the already besieged enclave in an act that under international law amounts to a war crime.

But what unfolds in the coming days and weeks has its seed in history.

For decades, Western media outlets, academics, military experts and world leaders have described the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as intractable, complicated and deadlocked.

Here’s a simple guide to break down one of the world’s longest-running conflicts:

What was the Balfour Declaration?

- More than 100 years ago, on November 2, 1917, Britain’s then-foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, wrote a letter addressed to Lionel Walter Rothschild, a figurehead of the British Jewish community.

- The letter was short – just 67 words – but its contents had a seismic effect on Palestine that is still felt to this day.

- It committed the British government to “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” and to facilitating “the achievement of this object”. The letter is known as the Balfour Declaration .

- In essence, a European power promised the Zionist movement a country where Palestinian Arab natives made up more than 90 percent of the population.

- A British Mandate was created in 1923 and lasted until 1948. During that period, the British facilitated mass Jewish immigration – many of the new residents were fleeing Nazism in Europe – and they also faced protests and strikes. Palestinians were alarmed by their country’s changing demographics and British confiscation of their lands to be handed over to Jewish settlers.

What happened during the 1930s?

- Escalating tensions eventually led to the Arab Revolt, which lasted from 1936 to 1939.

- In April 1936, the newly formed Arab National Committee called on Palestinians to launch a general strike, withhold tax payments and boycott Jewish products to protest British colonialism and growing Jewish immigration.

- The six-month strike was brutally repressed by the British, who launched a mass arrest campaign and carried out punitive home demolitions , a practice that Israel continues to implement against Palestinians today.

- The second phase of the revolt began in late 1937 and was led by the Palestinian peasant resistance movement, which targeted British forces and colonialism.

- By the second half of 1939, Britain had massed 30,000 troops in Palestine. Villages were bombed by air, curfews imposed, homes demolished, and administrative detentions and summary killings were widespread.

- In tandem, the British collaborated with the Jewish settler community and formed armed groups and a British-led “counterinsurgency force” of Jewish fighters named the Special Night Squads.

- Within the Yishuv, the pre-state settler community, arms were secretly imported and weapons factories established to expand the Haganah, the Jewish paramilitary that later became the core of the Israeli army.

- In those three years of revolt, 5,000 Palestinians were killed, 15,000 to 20,000 were wounded and 5,600 were imprisoned.

What was the UN partition plan?

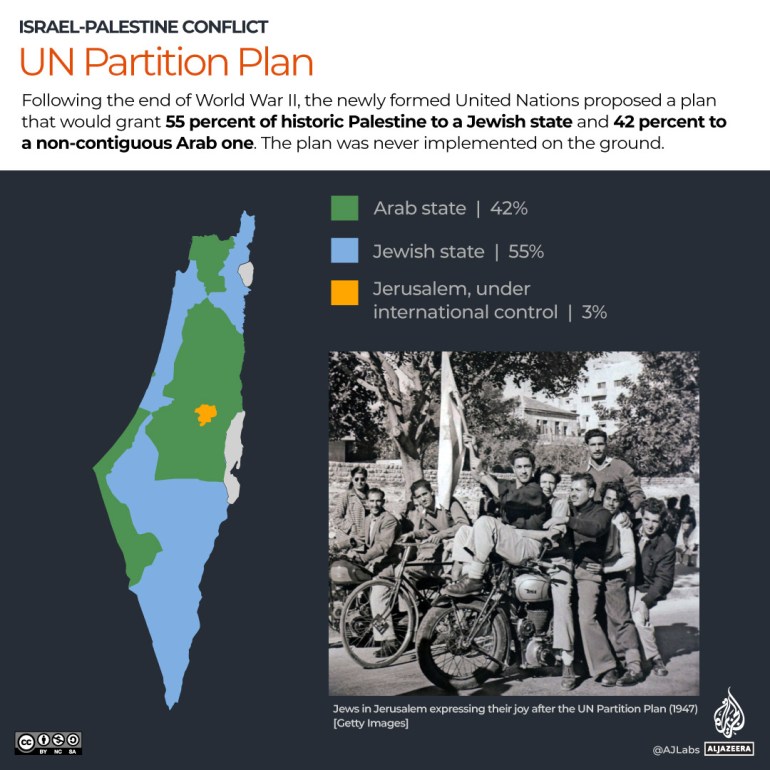

- By 1947, the Jewish population had ballooned to 33 percent of Palestine, but they owned only 6 percent of the land.

- The United Nations adopted Resolution 181, which called for the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states.

- The Palestinians rejected the plan because it allotted about 55 percent of Palestine to the Jewish state, including most of the fertile coastal region.

- At the time, the Palestinians owned 94 percent of historic Palestine and comprised 67 percent of its population.

The 1948 Nakba, or the ethnic cleansing of Palestine

- Even before the British Mandate expired on May 14, 1948, Zionist paramilitaries were already embarking on a military operation to destroy Palestinian towns and villages to expand the borders of the Zionist state that was to be born.

- In April 1948, more than 100 Palestinian men, women and children were killed in the village of Deir Yassin on the outskirts of Jerusalem.

- That set the tone for the rest of the operation, and from 1947 to 1949, more than 500 Palestinian villages, towns and cities were destroyed in what Palestinians refer to as the Nakba , or “catastrophe” in Arabic.

- An estimated 15,000 Palestinians were killed, including in dozens of massacres.

- The Zionist movement captured 78 percent of historic Palestine. The remaining 22 percent was divided into what are now the occupied West Bank and the besieged Gaza Strip.

- An estimated 750,000 Palestinians were forced out of their homes.

- Today their descendants live as six million refugees in 58 squalid camps throughout Palestine and in the neighbouring countries of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Egypt.

- On May 15, 1948, Israel announced its establishment.

- The following day, the first Arab-Israeli war began and fighting ended in January 1949 after an armistice between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria.

- In December 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194, which calls for the right of return for Palestinian refugees.

The years after the Nakba

- At least 150,000 Palestinians remained in the newly created state of Israel and lived under a tightly controlled military occupation for almost 20 years before they were eventually granted Israeli citizenship.

- Egypt took over the Gaza Strip, and in 1950, Jordan began its administrative rule over the West Bank.

- In 1964, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) was formed, and a year later, the Fatah political party was established.

The Naksa, or the Six-Day War and the settlements

- On June 5, 1967, Israel occupied the rest of historic Palestine, including the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Syrian Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula during the Six-Day War against a coalition of Arab armies.

- For some Palestinians, this led to a second forced displacement, or Naksa, which means “setback” in Arabic.

- In December 1967, the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine was formed. Over the next decade, a series of attacks and plane hijackings by leftist groups drew the world’s attention to the plight of the Palestinians.

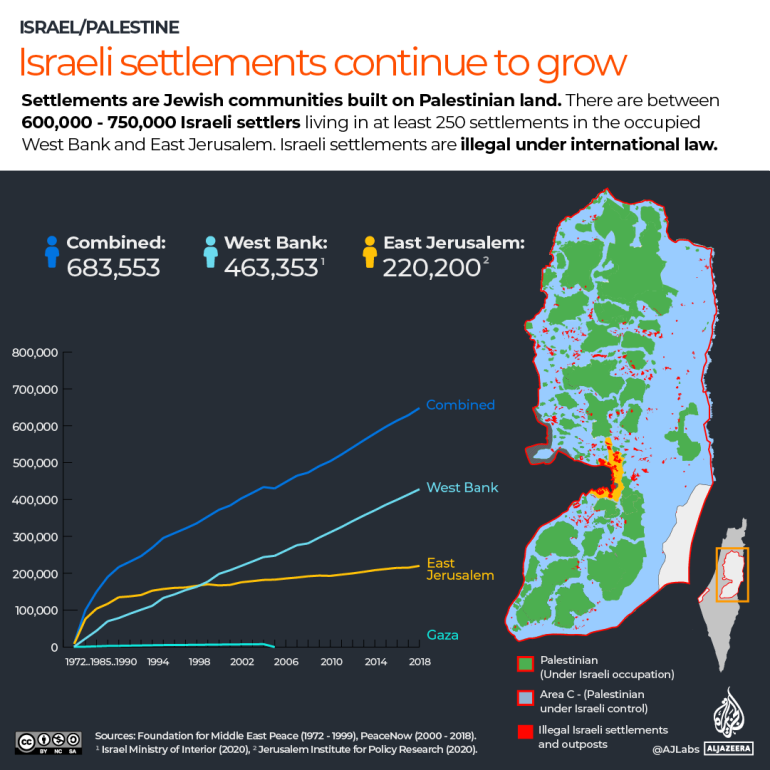

- Settlement construction began in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. A two-tier system was created with Jewish settlers afforded all the rights and privileges of being Israeli citizens whereas Palestinians had to live under a military occupation that discriminated against them and barred any form of political or civic expression.

The first Intifada 1987-1993

- The first Palestinian Intifada erupted in the Gaza Strip in December 1987 after four Palestinians were killed when an Israeli truck collided with two vans carrying Palestinian workers.

- Protests spread rapidly to the West Bank with young Palestinians throwing stones at Israeli army tanks and soldiers.

- It also led to the establishment of the Hamas movement, an off-shoot of the Muslim Brotherhood that engaged in armed resistance against the Israeli occupation.

- The Israeli army’s heavy-handed response was encapsulated by the “Break their Bones” policy advocated by then-Defence Minister Yitzhak Rabin. It included summary killings, closures of universities, deportations of activists and destruction of homes.

- The Intifada was primarily carried out by young people and was directed by the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising, a coalition of Palestinian political factions committed to ending the Israeli occupation and establishing Palestinian independence.

- In 1988, the Arab League recognised the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinian people.

- The Intifada was characterised by popular mobilisations, mass protests, civil disobedience, well-organised strikes and communal cooperatives.

- According to the Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem, 1,070 Palestinians were killed by Israeli forces during the Intifada, including 237 children. More than 175,000 Palestinians were arrested.

- The Intifada also prompted the international community to search for a solution to the conflict.

The Oslo years and the Palestinian Authority

- The Intifada ended with the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 and the formation of the Palestinian Authority (PA), an interim government that was granted limited self-rule in pockets of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.

- The PLO recognised Israel on the basis of a two-state solution and effectively signed agreements that gave Israel control of 60 percent of the West Bank, and much of the territory’s land and water resources.

- The PA was supposed to make way for the first elected Palestinian government running an independent state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip with its capital in East Jerusalem, but that has never happened.

- Critics of the PA view it as a corrupt subcontractor to the Israeli occupation that collaborates closely with the Israeli military in clamping down on dissent and political activism against Israel.

- In 1995, Israel built an electronic fence and concrete wall around the Gaza Strip, snapping interactions between the split Palestinian territories.

The second Intifada

- The second Intifada began on September 28, 2000, when Likud opposition leader Ariel Sharon made a provocative visit to the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound with thousands of security forces deployed in and around the Old City of Jerusalem.

- Clashes between Palestinian protesters and Israeli forces killed five Palestinians and injured 200 over two days.

- The incident sparked a widespread armed uprising. During the Intifada, Israel caused unprecedented damage to the Palestinian economy and infrastructure.

- Israel reoccupied areas governed by the Palestinian Authority and began construction of a separation wall that along with rampant settlement construction, destroyed Palestinian livelihoods and communities.

- Settlements are illegal under international law, but over the years, hundreds of thousands of Jewish settlers have moved to colonies built on stolen Palestinian land. The space for Palestinians is shrinking as settler-only roads and infrastructure slice up the occupied West Bank, forcing Palestinian cities and towns into bantustans, the isolated enclaves for Black South Africans that the country’s former apartheid regime created.

- At the time the Oslo Accords were signed, just over 110,000 Jewish settlers lived in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Today, the figure is more than 700,000 living on more than 100,000 hectares (390sq miles) of land expropriated from the Palestinians.

The Palestinian division and the Gaza blockade

- PLO leader Yasser Arafat died in 2004, and a year later, the second Intifada ended, Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip were dismantled, and Israeli soldiers and 9,000 settlers left the enclave.

- A year later, Palestinians voted in a general election for the first time.

- Hamas won a majority. However, a Fatah-Hamas civil war broke out, lasting for months, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of Palestinians.

- Hamas expelled Fatah from the Gaza Strip, and Fatah – the main party of the Palestinian Authority – resumed control of parts of the West Bank.

- In June 2007, Israel imposed a land, air and naval blockade on the Gaza Strip, accusing Hamas of “terrorism”.

The wars on the Gaza Strip

- Israel has launched four protracted military assaults on Gaza: in 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2021. Thousands of Palestinians have been killed, including many children , and tens of thousands of homes, schools and office buildings have been destroyed.

- Rebuilding has been next to impossible because the siege prevents construction materials, such as steel and cement, from reaching Gaza.

- The 2008 assault involved the use of internationally banned weaponry, such as phosphorus gas.

- In 2014, over a span of 50 days, Israel killed more than 2,100 Palestinians, including 1,462 civilians and close to 500 children.

- During the assault , called Operation Protective Edge by the Israelis, about 11,000 Palestinians were wounded, 20,000 homes were destroyed and half a million people displaced .

Settlements and the Israel-Palestine Conflict: Background Reading

Scholarship about Israeli settlement in occupied Palestinian territories provides historical context for recent violence in the region.

After a relatively dormant period, the Israel-Palestine conflict erupted into open war in May of 2021. Hamas in Gaza and the Israeli army engaged in the first sustained exchange of rocket fire and airstrikes in seven years. The near-term cause of the fighting was a series of disputes over the usage of the Al-Aqsa Mosque and nearby Wailing Wall in Jerusalem , as Israel’s national holidays conflicted with the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Moreover, both the governments of Israel and the Palestinian Authority are weak in 2021, discouraging either side from compromise. At that time, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu failed to attract the necessary cohort of far-right wing politicians to form a coalition government in Israel’s parliamentary system. The President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, canceled elections to avoid a potential loss. This emboldened Hamas, which broke with Abbas’ party Fatah in 2007 and has remained in sole control of Gaza since that time.

Audio brought to you by curio.io

However, the most important long-term factor has been the continuing Israeli efforts to displace Palestinian residents of the occupied Palestine territories and to settle Israeli citizens in their place. Israel occupied the Palestinian territories of Gaza and the West Bank in the 1967 war, which had been formerly under the administration of Egypt and Jordan, respectively. Israel has permitted hundreds of thousands of settlers to make land claims based on pre-1948 ownership in these territories, and to establish entirely new communities on land claimed by the state in the intervening decade. The UN has formally denounced this policy as a violation of international law.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

This long process also arrived at a significant turning point in early 2021, as Israel courts ordered several Palestinian families to vacate their Sheikh Jarrah homes, where many had lived for decades. Those official decrees to remove Palestinian families from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem near Al-Aqsa triggered Palestinian street protests and violent clashes involving Israeli police by May of 2021.

The following research available for free via the links below offers valuable insight and historical context on the topic of the Israeli settlements.

Joel Beinin, “Mixing, Separation and Violence in Urban Spaces and The Rural Frontier in Palestine,” The Arab Studies Journal , Spring 2013, Vol. 21, No. 1, TWENTIETH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE, pp. 14-47.

Beinin situates the phenomenon of the Israeli settlements in historical context. In the era of Ottoman Palestine and even the British mandate that followed World War I, Christian, Muslim and Jewish communities lived side-by-side in Palestine’s major cities Jerusalem and Jaffa. They socialized together and invested in each other’s business ventures as the Levant entered the industrial world. Although many early Zionist settlers, and the later Labor Zionist movement, idealized rural settlement and agriculture as the principal way of creating a Jewish homeland community, Beinin demonstrates that it was largely cities that Zionist immigrants moved to and sought to transform, both before and after the formation of Israel in 1948 and the 1967 war.

“Despite its preponderantly urban character, the post-1967 settlement project has produced a diametrically opposite model of urban life than the norms of late Ottoman Palestine—in practice and as the settlers’ ideal,” Beinin writes. “Jews exclusively inhabit all settlements—urban, suburban, or rural, ideologically or economically inspired—though Palestinians are often employed in them, even to construct them. All Jews are Israeli citizens with greater rights and subject to different laws and norms than their non-citizen neighbors.”

Janet Abu-Lughod, “Israeli Settlements in Occupied Arab Lands: Conquest to Colony,” Journal of Palestine Studies , Winter 1982, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 16-54.

Written only 15 years after the 1967 war, Abu-Lughod’s research provides valuable insight into Israel’s initial government and settlement strategies of the Palestinian territories. Although some right-wing politicians made immediate demands to annex Gaza and the West Bank, in spite of international law, most Israeli leaders realized that this would raise the question of giving citizenship to Palestinians. They then sought other means of legally expropriating land and diminishing the power of occupied Palestinians.

Indeed, Abu-Lughod argues Israel drew on the experience of urban planning inside Israel between 1948 and 1967 to diminish the concentration of Arab Israeli citizens in certain parts of the country when planning the distribution of occupied territory settlements. The justification for taking possession of this land comes “from the fiction of government succession.” The legal practice of freehold private property developed later in the Muslim world than in Europe, and much of the marginal land in the West Bank remained unregistered or in religious foundations (waqfs), which Israel claimed as state land after 1967. “While the confiscation and reassignment of ‘state land’ to Jewish settlers is inherently no more legitimate than any other form of expropriation, the Israelis have made much of this distinction between public and private ownership in their defensive arguments,” she writes.

Marina Sergides, “Housing in East Jerusalem: Marina Sergides reports on a legal mission to the Occupied Palestine Territory,” Socialist Lawyer , No. 60 (February 2012), pp. 14-17.

This is a deep dive into the social and legal situations of the Palestinian families in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem living on land with disputed ownership. Twenty-eight refugee families with 500 people had been living in homes they had built on land granted to them by UNRWH after fleeing from other homes inside Israel after its creation in 1948. Since 1967 and the Israeli declared annexation of East Jerusalem, the Nahalat Shimon company has brought Ottoman-era documents claiming some of the land in the neighborhood had been owned by Jewish families in the 19th century. It succeeded in forcing out four of the families in 2009.

Sergides questions of the legal proceedings of applying domestic Israeli law to Palestinians in territory recognized as occupied under international law. “Moreover, the delegation observed that there is an asymmetry in the way the Israeli courts treat the question of pre-1948 property rights,” she writes. “While the courts have been willing to uphold claims by Jewish organisations in relation to property in Sheikh Jarrah allegedly owned by Jewish families before 1948, similar claims by the Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah in relation to lands which their families owned in what is now the State of Israel would not be entertained.” She concludes by highlighting the ways Israeli demolitions of Palestinian homes and restriction on new construction is causing a housing crisis in East Jerusalem.

Raja Shehadeh, “From Jerusalem to the Rest of the West Bank,” Review of Middle East Studies , June 2019, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 6-19.

The most recent installment on this list, Shehadeh reviews the politics of settlement in recent decades in light of the Trump administration’s decision to move the US Embassy to Jerusalem, recognizing it as Israel’s capital on Dec. 6, 2017. In particular, he highlights the failures of the two-state solution to reconcile the existence of settlements within Palestinian territory, an inherent flaw in the 1990s’ Oslo Peace Accords.

The Accords divided land in the West Bank into three areas: A) Palestinian control; B) Palestinian civil control with Israeli military control and C) Full Israeli control. The resulting map is a Swiss cheese of administrative areas. Combined with Israel’s direct annexation of East Jerusalem, it divided Palestinian settlement into a patchwork difficult to govern. Although the PLO made these compromises to win recognition from Israel, the resulting devolution of political power only heightened the distinction between settlers, who enjoy citizenship rights and state services, and the disenfranchisement of Palestinians.

Joyce Dalsheim and Assaf Harel, “Representing Settlers,” Review of Middle East Studies , Winter 2009, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Winter 2009), pp. 219-238.

This review essay is a cultural critique of the way religious Israeli settlers are conceived in the news media and academic works. Works in both fields, Dalsheim and Harel write, depict these Israeli settlers as religious fundamentalists that are seeking both to create socially alienated communities and to fulfill a religious commitment to reclaim what they see as land promised them in the bible, despite international law. However much this reflects the truth for some communities, they argue it does not reflect the huge diversity of people actually settling in the occupied territories. Moreover, it serves as symbolic legitimization of other brands of Zionism.

“These representations of settlers not only portray religious settlers as categorically different from ‘ordinary’ or ‘mainstream’ Israelis, they also project a sense of moral legitimacy for those writing against the settlers,” Dalsheim and Harel argue. “They reaffirm a moral high ground for Israelis by inscribing a deep division between Israel inside its internationally recognized borders and its settlements in the post-1967 occupied territories.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Labor Day: A Celebration of Working in America

- A Selection of Student Confessions

- Thurgood Marshall

The Bawdy House Riots of 1668

Recent posts.

- Playing It Straight and Catching a Break

- Finding Caves on the Moon Is Great. On Mars? Even Better.

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

A Century of Conflict: Professor Eugene Rogan’s Historical Perspective on Israel-Palestine

Professor Eugene Rogan is a renowned scholar in Modern Middle Eastern History, serving as the Director of the Middle East Centre and a Fellow of St Antony's College at the University of Oxford. He authored The Arabs: A History —acclaimed by The Economist, The Financial Times, and The Atlantic Monthly as one of the best books of 2009—and his latest work, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, 1914-1920 , continues to contribute significantly to the field.

You have written extensively about the Ottoman Empire in The Fall of the Ottomans and Frontiers of the State in Late Ottoman Empire as well as more generally about Arab history in The Arabs . Where do you see the Israeli-Palestinian conflict fitting into this narrative?

Since 1948, and indeed well before, the conflict between the Zionist movement in Palestine and the emerging state of Israel was to define the Middle East as a zone of conflict. What was an Arab-Israeli conflict through the 1970s has, since the Camp David Accords, developed into a much more focused conflict between Israel and Palestine. There have been exceptions: Israel has fought wars in southern Lebanon against Hezbollah and has had small engagements with Syria. However, if you want to get to the heart of the unresolved, it really is Israel-Palestine. We can talk about a conflict that has endured unresolved since 1948 and continues to define the politics of the region and its place in the world.

You mention 1948—what do you see as the starting point of the Israel-Palestine conflict, and how have early events like the creation of modern Zionism, the Balfour Declaration, or the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 shaped its course?

Israel did not emerge from a vacuum in 1948. The 1917 Balfour Declaration is a really important point. Before 1917, Zionism was a very unrealistic nationalism, because the demography of the movement was in diaspora. Nationalism [is usually] based on the idea that the demography [is based] on a geography, [a] struggle for self-determination within the boundaries of a certain territory of land. Zionism was an appeal to Jews across four continents, and it took the support of a major power to take that idea from romantic and idealistic to something you could hope to act on. By gaining the direct support of the British government—not for the Zionist movement, not for the creation of a Jewish state, but at the very least for the creation of a Jewish national home—Zionism [was given] a political basis on which to begin to realize that dream of statehood.

More specifically, how did British policies and actions during the mandate period contribute to these growing tensions between Israeli and Arab populations?

I believe that Britain saw the Zionist movement as a partner for managing a new mandate and Palestine—a territory Britain had not designated as [a] desired addition to the British Empire until well into World War I. In my view, [this was] a reflection of [Britain’s] growing awareness of the vulnerability of the Suez Canal from Palestine, because Palestine was the last water source you had before the bone-dry Sinai Peninsula. Twice [during] World War I, the Ottomans had managed to strike the Suez Canal from Palestine across Sinai. It seems very clear deductively that the British came to recognize the strategic importance of Palestine but knew they would face resistance from the indigenous population to them coming in as a colonial power. They had hoped, in partnership with the Zionist movement, to have a community in Palestine that would work with their administration, and they envisaged a compact minority that [would] be dependent and reliable.