The turning point: Why we must transform education now

Global warming. Accelerated digital revolution. Growing inequalities. Democratic backsliding. Loss of biodiversity. Devastating pandemics. And the list goes on. These are just some of the most pressing challenges that we are facing today in our interconnected world.

The diagnosis is clear: Our current global education system is failing to address these alarming challenges and provide quality learning for everyone throughout life. We know that education today is not fulfilling its promise to help us shape peaceful, just, and sustainable societies. These findings were detailed in UNESCO’s Futures of Education Report in November 2021 which called for a new social contract for education.

That is why it has never been more crucial to reimagine the way we learn, what we learn and how we learn. The turning point is now. It’s time to transform education. How do we make that happen?

Here’s what you need to know.

Why do we need to transform education?

The current state of the world calls for a major transformation in education to repair past injustices and enhance our capacity to act together for a more sustainable and just future. We must ensure the right to lifelong learning by providing all learners - of all ages in all contexts - the knowledge and skills they need to realize their full potential and live with dignity. Education can no longer be limited to a single period of one’s lifetime. Everyone, starting with the most marginalized and disadvantaged in our societies, must be entitled to learning opportunities throughout life both for employment and personal agency. A new social contract for education must unite us around collective endeavours and provide the knowledge and innovation needed to shape a better world anchored in social, economic, and environmental justice.

What are the key areas that need to be transformed?

- Inclusive, equitable, safe and healthy schools

Education is in crisis. High rates of poverty, exclusion and gender inequality continue to hold millions back from learning. Moreover, COVID-19 further exposed the inequities in education access and quality, and violence, armed conflict, disasters and reversal of women’s rights have increased insecurity. Inclusive, transformative education must ensure that all learners have unhindered access to and participation in education, that they are safe and healthy, free from violence and discrimination, and are supported with comprehensive care services within school settings. Transforming education requires a significant increase in investment in quality education, a strong foundation in comprehensive early childhood development and education, and must be underpinned by strong political commitment, sound planning, and a robust evidence base.

- Learning and skills for life, work and sustainable development

There is a crisis in foundational learning, of literacy and numeracy skills among young learners. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, learning poverty has increased by a third in low- and middle-income countries, with an estimated 70% of 10-year-olds unable to understand a simple written text. Children with disabilities are 42% less likely to have foundational reading and numeracy skills compared to their peers. More than 771 million people still lack basic literacy skills, two-thirds of whom are women. Transforming education means empowering learners with knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to be resilient, adaptable and prepared for the uncertain future while contributing to human and planetary well-being and sustainable development. To do so, there must be emphasis on foundational learning for basic literacy and numeracy; education for sustainable development, which encompasses environmental and climate change education; and skills for employment and entrepreneurship.

- Teachers, teaching and the teaching profession

Teachers are essential for achieving learning outcomes, and for achieving SDG 4 and the transformation of education. But teachers and education personnel are confronted by four major challenges: Teacher shortages; lack of professional development opportunities; low status and working conditions; and lack of capacity to develop teacher leadership, autonomy and innovation. Accelerating progress toward SDG 4 and transforming education require that there is an adequate number of teachers to meet learners’ needs, and all education personnel are trained, motivated, and supported. This can only be possible when education is adequately funded, and policies recognize and support the teaching profession, to improve their status and working conditions.

- Digital learning and transformation

The COVID-19 crisis drove unprecedented innovations in remote learning through harnessing digital technologies. At the same time, the digital divide excluded many from learning, with nearly one-third of school-age children (463 million) without access to distance learning. These inequities in access meant some groups, such as young women and girls, were left out of learning opportunities. Digital transformation requires harnessing technology as part of larger systemic efforts to transform education, making it more inclusive, equitable, effective, relevant, and sustainable. Investments and action in digital learning should be guided by the three core principles: Center the most marginalized; Free, high-quality digital education content; and Pedagogical innovation and change.

- Financing of education

While global education spending has grown overall, it has been thwarted by high population growth, the surmounting costs of managing education during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the diversion of aid to other emergencies, leaving a massive global education financial gap amounting to US$ 148 billion annually. In this context, the first step toward transformation is to urge funders to redirect resources back to education to close the funding gap. Following that, countries must have significantly increased and sustainable financing for achieving SDG 4 and that these resources must be equitably and effectively allocated and monitored. Addressing the gaps in education financing requires policy actions in three key areas: Mobilizing more resources, especially domestic; increasing efficiency and equity of allocations and expenditures; and improving education financing data. Finally, determining which areas needs to be financed, and how, will be informed by recommendations from each of the other four action tracks .

What is the Transforming Education Summit?

UNESCO is hosting the Transforming Education Pre-Summit on 28-30 June 2022, a meeting of over 140 Ministers of Education, as well as policy and business leaders and youth activists, who are coming together to build a roadmap to transform education globally. This meeting is a precursor to the Transforming Education Summit to be held on 19 September 2022 at the UN General Assembly in New York. This high-level summit is convened by the UN Secretary General to radically change our approach to education systems. Focusing on 5 key areas of transformation, the meeting seeks to mobilize political ambition, action, solutions and solidarity to transform education: to take stock of efforts to recover pandemic-related learning losses; to reimagine education systems for the world of today and tomorrow; and to revitalize national and global efforts to achieve SDG-4.

- More on the Transforming Education Summit

- More on the Pre-Summit

Related items

- Future of education

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent news

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

America's Education News Source

Copyright 2024 The 74 Media, Inc

- EDlection 2024

- Hope Rises in Pine Bluff

- Artificial Intelligence

- science of reading

Best Education Articles of 2022: Our 22 Most Shared Stories About Students & Schools

Amid a fourth school year disrupted by covid, our 22 most discussed articles about learning loss, student safety, innovation, mental health & more.

Every December at The 74, we take a moment to recap and spotlight our most read, shared and debated education articles of the year. Looking back now at our time capsules from December 2020 and December 2021 , one can chart the rolling impact of the pandemic on America’s students, families and school communities. Two years ago, we were just beginning to process the true cost of emergency classroom closures across the country and the depth of students’ unfinished learning. Last year, as we looked back in the shadow of Omicron, a growing sense of urgency to get kids caught up was colliding with bureaucratic and logistical challenges in figuring out how to rapidly convert federal relief funds into meaningful, scalable student assistance.

This year’s list, publishing amid new calls for mask mandates and yet another spike in hospitalizations, powerfully frames our surreal new normal: mounting concerns about historic test score declines; intensifying political divides that would challenge school systems even if there weren’t simultaneous health, staffing and learning crises to manage; broader economic stresses that are making it harder to manage school systems; and a sustained push by many educators and families to embrace innovations and out-of-the-box thinking to help kids accelerate their learning by any means necessary.

Now, 2½ years into one of the most turbulent periods in the history of American education, these were our 22 most discussed articles of 2022:

The COVID School Years: 700 Days Since Lockdown

Learning Loss: 700 days. As we reported Feb. 14, that’s how long it had been since more than half the nation’s schools crossed into the pandemic era. On March 16, 2020, districts in 27 states, encompassing almost 80,000 schools, closed their doors for the first long educational lockdown. Since then, schools have reopened, closed and reopened again. The effects have been immediate — students lost parents, teachers mourned fallen colleagues — and hopelessly abstract as educators weighed “pandemic learning loss,” the sometimes crude measure of COVID’s impact on students’ academic performance.

With spring approaching, there were reasons to be hopeful. More children had been vaccinated. Mask mandates were ending. But even if the pandemic recedes and a “new normal” emerges, there are clear signs that the issues surfaced during this period will linger. COVID heightened inequities that have long been baked into the American educational system. The social contract between parents and schools has frayed. And teachers are burning out. To mark a third spring of educational disruption, Linda Jacobson interviewed educators, parents, students and researchers who spoke movingly, often unsparingly, about what Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, called “a seismic interruption to education unlike anything we’ve ever seen.” Read her full report .

- A 700-Day Parental Awakening : Marguerite Roza, of Georgetown’s Edunomics Lab, reflects on the past years

- 700 Days of Missed Opportunities — and Lingering Inequities : Robin Lake, of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, looks back (and forwards)

- 700 Days of Balancing Student Safety Against Keeping Classrooms Open : Superintendent Pedro Martinez reflects

- 700 Days in Pictures : 24 months inside one resilient school district

- The COVID School Years : See our special report, looking back on 700 days of the pandemic

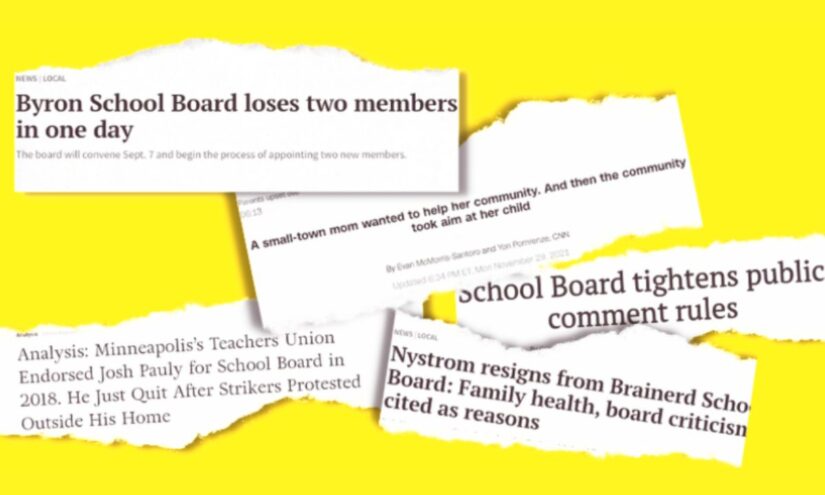

Threatened & Trolled, School Board Members Quit in Record Numbers

School Leadership : By the time we published this report in May, the chaos and violence at big city school board meetings had dominated headlines for months, as protesters, spurred by ideological interest groups and social media campaigns, railed about race, gender and a host of other hot-button issues. But what does it look like when the boardroom is located in a small community, where the elected officials under fire often have lifelong ties to the people doing the shouting? Over the last 18 months, Minnesota K-12 districts have seen a record number of board members resign before the end of their term. As one said in a tearful explanation to her constituents, “The hate is just too much.” Beth Hawkins takes a look at the possible ramifications .

- Million-Dollar Records Request : From COVID and critical race theory to teachers’ names & schools, districts flooded with freedom of information document demands

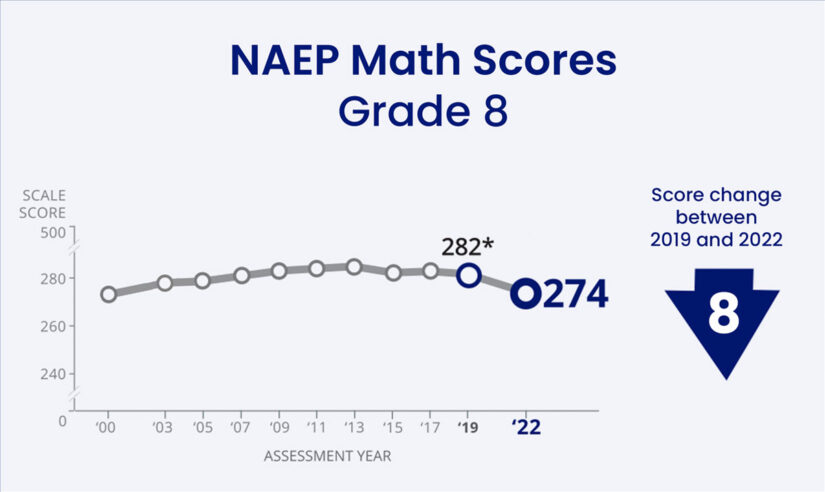

Nation’s Report Card Shows Largest Drops Ever Recorded in 4th and 8th Grade Math

Student Achievement : In a moment the education world had anxiously awaited, the latest round of scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress were released in October — and the news was harsh. Math scores saw the largest drops in the history of the exam, while reading performance also fell in a majority of states. National Center for Education Statistics Commissioner Peggy Carr said the “decline that we’re seeing in the math data is stark. It is troubling. It is significant.” Even as some state-level data has shown evidence of a rebound this year, federal officials warned COVID-19’s lost learning won’t be easily restored. The 74’s Kevin Mahnken breaks down the results .

- Lost Decades : ‘Nation’s Report Card’ shows 20 years of growth wiped out by two years of pandemic

- Economic Toll : Damage from NAEP math losses could total nearly $1 trillion

- COVID Recovery : Can districts rise to the challenge of new NAEP results? Outlook’s not so good

Virtual Nightmare: One Student’s Journey Through the Pandemic

Mental Health : As the debate over the lingering effects of school closures continues, the term “pandemic recovery” can often lose its meaning. For Jason Finuliar, a California teen whose Bay Area school district was among those shuttered the longest, the journey has been painful and slow. Once a happy, high-achieving student, he descended into academic failure and a depression so severe that he spent 10 days in a residential mental health facility. “I felt so worthless,” he said. It’s taking compassionate counselors, professional help and parents determined to save their son for Jason to regain hope for the future. Linda Jacobson reports .

16 Under 16: Meet The 74’s 2022 Class of STEM Achievers

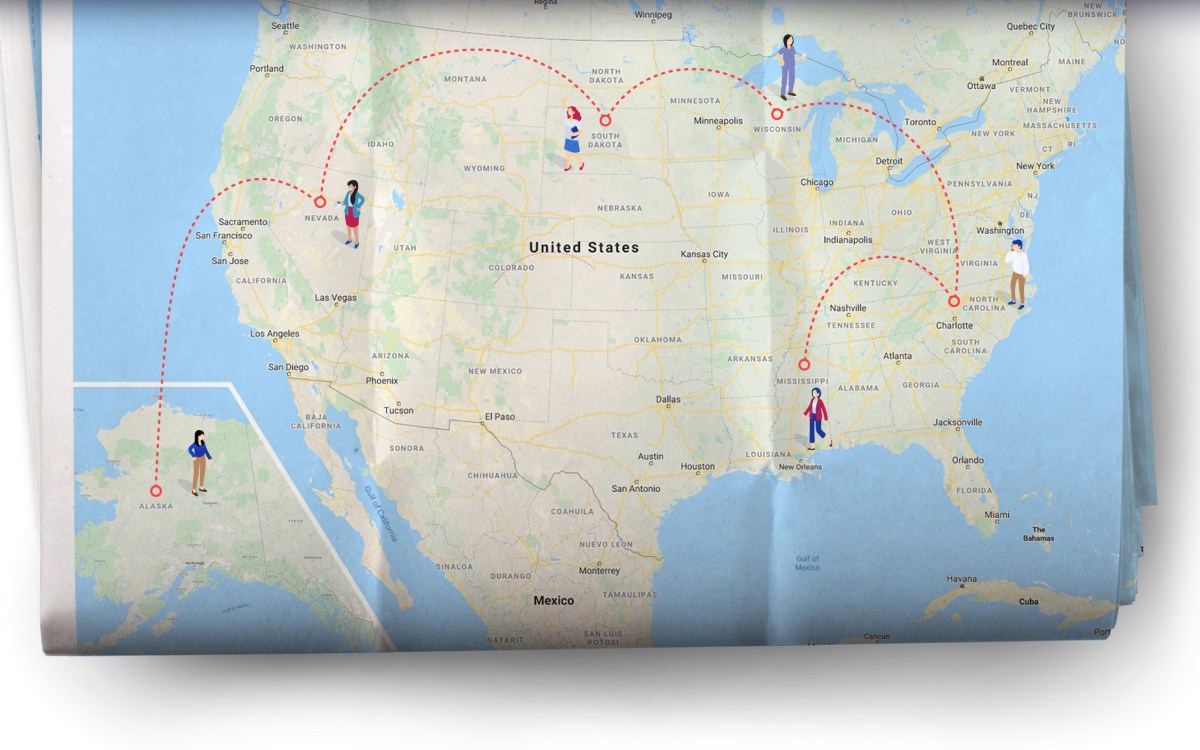

This spring, we asked for the country’s help identifying some of the most impressive students, age 16 or younger, who have shown extraordinary achievement in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. After an extensive and comprehensive selection process, we’re thrilled to introduce this year’s class of 16 Under 16 in STEM. The honorees range in age from 12 to 16, specialize in fields from medicine to agriculture to invention and represent the country from coast to coast. We hope these incredible youngsters can inspire others — and offer reassurance that our future can be in pretty good hands. Emmeline Zhao offers a closeup of the 2022 class of 16 Under 16 in STEM — click here to read and watch more about them .

A ‘National Teacher Shortage’? New Research Reveals Vastly Different Realities Between States & Regions

School Staffing : Adding to efforts to understand America’s teacher shortages, a new report and website maps the K-12 teaching vacancy data. Nationally, an estimated 36,504 full-time teacher positions are unfilled, with shortages currently localized in nine states. “There are substantial vacant teacher positions in the United States. And for some states, this is much higher than for other states. … It’s just a question of how severe it is,” said author Tuan Nguyen. Marianna McMurdock reports on America’s uneven crisis .

Meet the Gatekeepers of Students’ Private Lives

School Surveillance : Megan Waskiewicz used to sit at the top of the bleachers and hide her face behind the glow of a laptop monitor. While watching one of her five children play basketball on the court below, the Pittsburgh mother didn’t want other parents in the crowd to know she was also looking at child porn. Waskiewicz worked on contract as a content moderator for Gaggle, a surveillance company that monitors the online behaviors of some 5 million students across the U.S. on their school-issued Google and Microsoft accounts in an effort to prevent youth violence and self-harm. As a result, kids’ deepest secrets — like nude selfies and suicide notes — regularly flashed onto Waskiewicz’s screen. Waskiewicz and other former moderators at Gaggle believe the company helped protect kids, but they also surfaced significant questions about its efficacy, employment practices and effect on students’ civil rights. Eight former moderators shared their experiences at Gaggle with The 74, describing insufficient safeguards to protect students’ sensitive data, a work culture that prioritized speed over quality, scheduling issues that sent them scrambling to get hours and frequent exposure to explicit content that left some traumatized. Read the latest investigation by The 74’s Mark Keierleber .

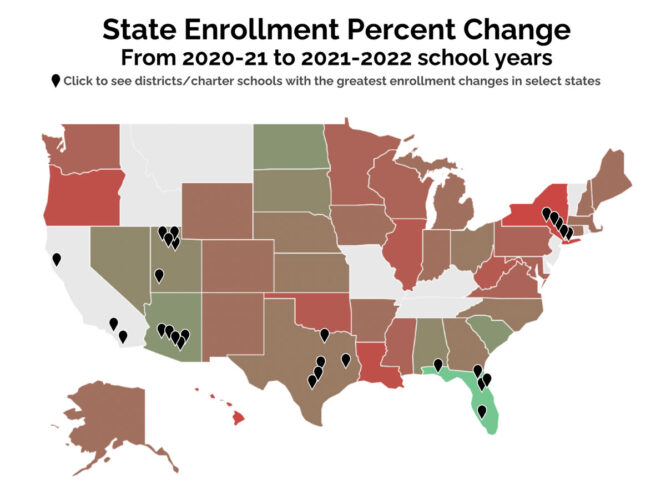

Students Continue to Flee Urban Districts as Boom Towns, Virtual Schools Thrive

Exclusive Data : A year after the nation’s schools experienced a historic decline in enrollment, data shows many urban districts are still losing students, and those that rebounded this year typically haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels. Of 40 states and the District of Columbia, few have seen more than a 1% increase compared with 2020-21, when some states experienced declines as high as 5%, according to data from Burbio, a company that tracks COVID-related education trends. Flat enrollment this year “means those kids did not come back,” said Thomas Dee, an education professor at Stanford University. While many urban districts were already losing students before the pandemic, COVID “accelerated” movement into outlying areas and to states with stronger job markets. Experts say that means many districts will have to make some tough decisions in the coming years. Linda Jacobson reports .

‘Hybrid’ Homeschooling Making Inroads as Families Seek New Models

School Choice : As public school enrollments dip to historic lows, researchers are beginning to track families to hybrid homeschooling arrangements that meet in person a few days per week and send students home for the rest of the time. More formal than learning pods or microschools, many still rely on parents for varying levels of instruction and grading. About 60% to 70% are private, according to a new research center on hybrid schools based at Kennesaw State University, northwest of Atlanta. Greg Toppo reports .

Educators’ ‘Careless’ Child Abuse Reports Devastate Thousands of NYC Families

Student Safety : Thousands of times every year, New York City school staff report what they fear may be child abuse or neglect to a state hotline. But the vast majority of the resulting investigations yield no evidence of maltreatment while plunging the families, most of them Black, Hispanic and low income, into fear and lasting trauma. Teachers are at the heart of the problem: From August 2019 to January 2022, two-thirds of their allegations were false alarms, data obtained by The 74 show. “Teachers, out of fear that they’re going to get in trouble, will report even if they’re just like, ‘Well, it could be abuse.’ … It also could be 10 million other things,” one Bronx teacher said. Read Asher Lehrer-Small’s report .

The Contagion Effect: From Buffalo to Uvalde, 16 Mass Shootings in Just 10 Days

Gun Violence : May’s mass school shooting in Texas — the deadliest campus attack in about a decade — has refocused attention on the frequency of such devastating carnage on American victims. The tragedy unfolded just 10 days after a mass shooting at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York. It could be more than a coincidence: A growing body of research suggests these assaults have a tendency to spread like a viral disease. In fact, The U.S. has experienced 16 mass shootings with at least four victims in just 10 days. Read Mark Keierleber’s report .

Teachers Leaving Jobs During Pandemic Find ‘Fertile’ Ground in New School Models

Microschools : Feeling that she could no longer effectively meet children’s needs in a traditional school, former counselor Heather Long is among those who left district jobs this year to teach in an alternative model — a microschool based in her New Hampshire home. “For the first time in their lives, they have options,” Jennifer Carolan of Reach Capital, an investment firm supporting online programs and ed tech ventures, told reporter Linda Jacobson. Some experts wonder if microschools are sustainable, but others say the ground is “fertile.” Read our full report .

Facing Pandemic Learning Crisis, Districts Spend Relief Funds at a Snail’s Pace

School Funding : Schools that were closed the longest due to COVID have spent just a fraction of the billions in federal relief funds targeted to students who suffered the most academically, according to an analysis by The 74. The delay is significant, experts say, because research points to a direct correlation between the closures and lost learning. Of the 25 largest districts, the 12 that were in remote learning for at least half the 2020-21 school year have spent on average roughly 15% of their American Rescue Plan funds — and districts are increasing pressure on the Education Department for more time. Linda Jacobson reports .

Slave Money Paved the Streets. Now, This Posh Rhode Island City Strives to Teach Its Past

Teaching History : Every year, millions of tourists marvel at Newport, Rhode Island’s colonial architecture, savor lobster rolls on the wharf and gaze at waters that — many don’t realize — launched more slave trading voyages than anywhere else in North America. But after years of invisibility, that obscured chapter is becoming better known, partly because the Ocean State passed a law in 2021 requiring schools to teach Rhode Island’s “African Heritage History.” Amid recent headlines that the state’s capital city is now moving forward with a $10 million reparations program, read Asher Lehrer-Small’s examination of how Newport is looking to empower schools to confront the city’s difficult past .

Harvard Economist Thomas Kane on Learning Loss, and Why Many Schools Aren’t Prepared to Combat It

74 Interview : This spring, Harvard economist Thomas Kane co-authored one of the biggest — and most pessimistic — studies yet of COVID learning loss, revealing that school closures massively set back achievement for low-income students. The effects appear so large that, by his estimates, many schools will need to spend 100% of their COVID relief to counteract them. Perversely, though, many in the education world don’t realize that yet. “Once that sinks in,” he said, “I think people will realize that more aggressive action is necessary.” Read Kevin Mahnken’s full interview .

In White, Wealthy Douglas County, Colorado, a Conservative School Board Majority Fires the Superintendent, and Fierce Backlash Ensues

Politics : The 2021 election of four conservative members to Colorado’s Douglas County school board led to the firing in February of schools Superintendent Corey Wise, who had served the district in various capacities for 26 years. The decision, which came at a meeting where public comment was barred, swiftly mobilized teachers, students and community members in opposition. Wise’s ouster came one day after a 1,500-employee sickout forced the shutdown of the state’s third-largest school district . A few days later, students walked out of school en masse, followed by litigation and talk of a school board recall effort. The battle mirrors those being fought in numerous districts throughout the country, with conservative parents, newly organized during the pandemic, championing one agenda and more moderate and liberal parent groups beginning to rise up to counter those views. Jo Napolitano reports .

Weaving Stronger School Communities: Nebraska’s Teacher of the Year Challenges Her Rural Community to Wrestle With the World

Inspiring : Residents of tiny Taylor, Nebraska, call Megan Helberg a “returner” — one of the few kids to grow up in the town of 190 residents, leave to attend college in the big city and then return as an adult to rejoin this rural community in the Sandhills. Honored as the state’s 2020 Teacher of the Year, Helberg says she sees her role as going well beyond classroom lessons and academics. She teaches her students to value their deep roots in this close-knit circle. She advocates on behalf of her school — the same school she attended as a child — which is always threatened with closure due to small class sizes. She has also launched travel clubs through her schools, which Helberg says has strengthened her community by breaking students, parents and other community members out of their comfort zone and helping them gain a better view of the world outside Nebraska while also seeing their friends and neighbors in a whole new light. This past winter, as part of a broader two-month series on educators weaving community, a team from The 74 made multiple visits to Taylor to meet Helberg and see her in action with her students. Watch the full documentary by Jim Fields, and read our full story about Helberg’s background and inspiration by Laura Fay .

Other profiles from this year’s Weaver series:

- Texas’s Alejandro Salazar : The band teacher who kept his school community connected through COVID’s chaos

- Hawaii’s Heidi Maxie : How an island teacher builds community bridges through her Hawaii school

- Georgia’s Allie Reeser : Living and learning among refugees in the ‘Ellis Island of the South’

- See the full series : Meet 12 educators strengthening school communities amid the pandemic

Research: Babies Born During COVID Talk Less with Caregivers, Slower to Develop Critical Language Skills

Big Picture : Independent studies by Brown University and a national nonprofit focused on early language development found infants born during the pandemic produced significantly fewer vocalizations and had less verbal back-and-forth with their caretakers compared with those born before COVID. Both used the nonprofit LENA’s “talk pedometer” technology, which delivers detailed information on what children hear throughout the day, including the number of words spoken near the child and the child’s own language-related vocalizations. It also counts child-adult interactions, called “conversational turns,” which are critical to language acquisition. The joint finding is the latest troubling evidence of developmental delays discovered when comparing babies born before and after COVID. “I’m worried about how we set things up going forward such that our early childhood teachers and early childhood interventionalists are prepared for what is potentially a set of children who maybe aren’t performing as we expect them to,” Brown’s Sean Deoni tells The 74’s Jo Napolitano. Read our full report .

Minneapolis Teacher Strike Lasted 3 Weeks. The Fallout Will Be Felt for Years

Two days after Minneapolis teachers ended their first strike in 50 years this past May, Superintendent Ed Graff walked out of a school board meeting, ostensibly because a student protester had used profanity. The next morning, he resigned. The swearing might have been the last straw, but the kit-bag of problems left unresolved by the district’s agreement with the striking unions is backbreaking indeed. Four-fifths of the district’s federal pandemic aid is now committed to staving off layoffs and giving classroom assistants and teachers bonuses and raises, leaving little for academic recovery at a moment when the percentage of disadvantaged students performing at grade level has dipped into the single digits. From potential school closures and misinformation about how much money the district actually has to layoffs of Black teachers, a lack of diversity in the workforce and how to make up for lost instructional time, Beth Hawkins reports on the aftermath .

After Steering Mississippi’s Unlikely Learning Miracle, Carey Wright Steps Down

Profile : Mississippi, one of America’s poorest and least educated states, emerged in 2019 as a fast-rising exemplar in math and reading growth. The transformation of the state’s long-derided school system came about through intense work — in the classroom and the statehouse — to raise learning standards, overhaul reading instruction and reinvent professional development. And with longtime State Superintendent Carey Wright retiring at the end of June, The 74’s Kevin Mahnken looked at what comes next .

As Schools Push for More Tutoring, New Research Points to Its Effectiveness — and the Challenge of Scaling it to Combat Learning Loss

Learning Acceleration : In the two years that COVID-19 has upended schooling for millions of families, experts and education leaders have increasingly touted one tool as a means for coping with learning loss: personalized tutors. In February, just days after the secretary of education declared that every struggling student should receive 90 minutes of tutoring each week, a newly released study offers more evidence of the strategy’s potential — and perhaps its limitations. An online tutoring pilot launched last spring did yield modest, if positive, learning benefits for the hundreds of middle schoolers who participated. But those gains were considerably smaller than the impressive results from some previous studies, perhaps because of the project’s design: It relied on lightly trained volunteers, rather than professional educators, and held its sessions online instead of in person. “There is a tradeoff in navigating the current climate where what is possible might not be scalable,” the study’s co-author, Matthew Kraft, told The 74’s Kevin Mahnken. “So instead of just saying, ‘Come hell or high water, I’m going to build a huge tutoring program,’ we might be better off starting off with a small program and building it over time.” Read our full report .

Florida Teen Invents World’s First Sustainable Electric Vehicle Motor

STEM : Robert Sansone was born to invent. His STEM creations range from springy leg extensions for sprinting to a go-kart that can reach speeds of 70 mph. But his latest project aims to solve a global problem: the unsustainability of electric car motors that use rare earth materials that are nonrenewable, expensive and pollute the environment during the mining and refining process. In Video Director James Field’s video profile, the Florida high schooler talks about his creation, inspiration and what he plans to do with his $75,000 prize from the 2022 Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair. Learn more right here , and watch our full portrait below:

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Steve Snyder is CEO of The 74

- best of 2022

- best of the month

- education reform

- learning recovery

- school innovations

- school safety

- Student Privacy

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74's republishing terms.

Best of 2022: The Year’s Top Stories About Education & America’s Schools

By Steve Snyder

This story first appeared at The 74 , a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

On The 74 Today

- Our Mission

The 10 Most Significant Education Studies of 2020

We reviewed hundreds of educational studies in 2020 and then highlighted 10 of the most significant—covering topics from virtual learning to the reading wars and the decline of standardized tests.

In the month of March of 2020, the year suddenly became a whirlwind. With a pandemic disrupting life across the entire globe, teachers scrambled to transform their physical classrooms into virtual—or even hybrid—ones, and researchers slowly began to collect insights into what works, and what doesn’t, in online learning environments around the world.

Meanwhile, neuroscientists made a convincing case for keeping handwriting in schools, and after the closure of several coal-fired power plants in Chicago, researchers reported a drop in pediatric emergency room visits and fewer absences in schools, reminding us that questions of educational equity do not begin and end at the schoolhouse door.

1. To Teach Vocabulary, Let Kids Be Thespians

When students are learning a new language, ask them to act out vocabulary words. It’s fun to unleash a child’s inner thespian, of course, but a 2020 study concluded that it also nearly doubles their ability to remember the words months later.

Researchers asked 8-year-old students to listen to words in another language and then use their hands and bodies to mimic the words—spreading their arms and pretending to fly, for example, when learning the German word flugzeug , which means “airplane.” After two months, these young actors were a remarkable 73 percent more likely to remember the new words than students who had listened without accompanying gestures. Researchers discovered similar, if slightly less dramatic, results when students looked at pictures while listening to the corresponding vocabulary.

It’s a simple reminder that if you want students to remember something, encourage them to learn it in a variety of ways—by drawing it , acting it out, or pairing it with relevant images , for example.

2. Neuroscientists Defend the Value of Teaching Handwriting—Again

For most kids, typing just doesn’t cut it. In 2012, brain scans of preliterate children revealed crucial reading circuitry flickering to life when kids hand-printed letters and then tried to read them. The effect largely disappeared when the letters were typed or traced.

More recently, in 2020, a team of researchers studied older children—seventh graders—while they handwrote, drew, and typed words, and concluded that handwriting and drawing produced telltale neural tracings indicative of deeper learning.

“Whenever self-generated movements are included as a learning strategy, more of the brain gets stimulated,” the researchers explain, before echoing the 2012 study: “It also appears that the movements related to keyboard typing do not activate these networks the same way that drawing and handwriting do.”

It would be a mistake to replace typing with handwriting, though. All kids need to develop digital skills, and there’s evidence that technology helps children with dyslexia to overcome obstacles like note taking or illegible handwriting, ultimately freeing them to “use their time for all the things in which they are gifted,” says the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity.

3. The ACT Test Just Got a Negative Score (Face Palm)

A 2020 study found that ACT test scores, which are often a key factor in college admissions, showed a weak—or even negative —relationship when it came to predicting how successful students would be in college. “There is little evidence that students will have more college success if they work to improve their ACT score,” the researchers explain, and students with very high ACT scores—but indifferent high school grades—often flamed out in college, overmatched by the rigors of a university’s academic schedule.

Just last year, the SAT—cousin to the ACT—had a similarly dubious public showing. In a major 2019 study of nearly 50,000 students led by researcher Brian Galla, and including Angela Duckworth, researchers found that high school grades were stronger predictors of four-year-college graduation than SAT scores.

The reason? Four-year high school grades, the researchers asserted, are a better indicator of crucial skills like perseverance, time management, and the ability to avoid distractions. It’s most likely those skills, in the end, that keep kids in college.

4. A Rubric Reduces Racial Grading Bias

A simple step might help undercut the pernicious effect of grading bias, a new study found: Articulate your standards clearly before you begin grading, and refer to the standards regularly during the assessment process.

In 2020, more than 1,500 teachers were recruited and asked to grade a writing sample from a fictional second-grade student. All of the sample stories were identical—but in one set, the student mentions a family member named Dashawn, while the other set references a sibling named Connor.

Teachers were 13 percent more likely to give the Connor papers a passing grade, revealing the invisible advantages that many students unknowingly benefit from. When grading criteria are vague, implicit stereotypes can insidiously “fill in the blanks,” explains the study’s author. But when teachers have an explicit set of criteria to evaluate the writing—asking whether the student “provides a well-elaborated recount of an event,” for example—the difference in grades is nearly eliminated.

5. What Do Coal-Fired Power Plants Have to Do With Learning? Plenty

When three coal-fired plants closed in the Chicago area, student absences in nearby schools dropped by 7 percent, a change largely driven by fewer emergency room visits for asthma-related problems. The stunning finding, published in a 2020 study from Duke and Penn State, underscores the role that often-overlooked environmental factors—like air quality, neighborhood crime, and noise pollution—have in keeping our children healthy and ready to learn.

At scale, the opportunity cost is staggering: About 2.3 million children in the United States still attend a public elementary or middle school located within 10 kilometers of a coal-fired plant.

The study builds on a growing body of research that reminds us that questions of educational equity do not begin and end at the schoolhouse door. What we call an achievement gap is often an equity gap, one that “takes root in the earliest years of children’s lives,” according to a 2017 study . We won’t have equal opportunity in our schools, the researchers admonish, until we are diligent about confronting inequality in our cities, our neighborhoods—and ultimately our own backyards.

6. Students Who Generate Good Questions Are Better Learners

Some of the most popular study strategies—highlighting passages, rereading notes, and underlining key sentences—are also among the least effective. A 2020 study highlighted a powerful alternative: Get students to generate questions about their learning, and gradually press them to ask more probing questions.

In the study, students who studied a topic and then generated their own questions scored an average of 14 percentage points higher on a test than students who used passive strategies like studying their notes and rereading classroom material. Creating questions, the researchers found, not only encouraged students to think more deeply about the topic but also strengthened their ability to remember what they were studying.

There are many engaging ways to have students create highly productive questions : When creating a test, you can ask students to submit their own questions, or you can use the Jeopardy! game as a platform for student-created questions.

7. Did a 2020 Study Just End the ‘Reading Wars’?

One of the most widely used reading programs was dealt a severe blow when a panel of reading experts concluded that it “would be unlikely to lead to literacy success for all of America’s public schoolchildren.”

In the 2020 study , the experts found that the controversial program—called “Units of Study” and developed over the course of four decades by Lucy Calkins at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project—failed to explicitly and systematically teach young readers how to decode and encode written words, and was thus “in direct opposition to an enormous body of settled research.”

The study sounded the death knell for practices that de-emphasize phonics in favor of having children use multiple sources of information—like story events or illustrations—to predict the meaning of unfamiliar words, an approach often associated with “balanced literacy.” In an internal memo obtained by publisher APM, Calkins seemed to concede the point, writing that “aspects of balanced literacy need some ‘rebalancing.’”

8. A Secret to High-Performing Virtual Classrooms

In 2020, a team at Georgia State University compiled a report on virtual learning best practices. While evidence in the field is "sparse" and "inconsistent," the report noted that logistical issues like accessing materials—and not content-specific problems like failures of comprehension—were often among the most significant obstacles to online learning. It wasn’t that students didn’t understand photosynthesis in a virtual setting, in other words—it was that they didn’t find (or simply didn't access) the lesson on photosynthesis at all.

That basic insight echoed a 2019 study that highlighted the crucial need to organize virtual classrooms even more intentionally than physical ones. Remote teachers should use a single, dedicated hub for important documents like assignments; simplify communications and reminders by using one channel like email or text; and reduce visual clutter like hard-to-read fonts and unnecessary decorations throughout their virtual spaces.

Because the tools are new to everyone, regular feedback on topics like accessibility and ease of use is crucial. Teachers should post simple surveys asking questions like “Have you encountered any technical issues?” and “Can you easily locate your assignments?” to ensure that students experience a smooth-running virtual learning space.

9. Love to Learn Languages? Surprisingly, Coding May Be Right for You

Learning how to code more closely resembles learning a language such as Chinese or Spanish than learning math, a 2020 study found—upending the conventional wisdom about what makes a good programmer.

In the study, young adults with no programming experience were asked to learn Python, a popular programming language; they then took a series of tests assessing their problem-solving, math, and language skills. The researchers discovered that mathematical skill accounted for only 2 percent of a person’s ability to learn how to code, while language skills were almost nine times more predictive, accounting for 17 percent of learning ability.

That’s an important insight because all too often, programming classes require that students pass advanced math courses—a hurdle that needlessly excludes students with untapped promise, the researchers claim.

10. Researchers Cast Doubt on Reading Tasks Like ‘Finding the Main Idea’

“Content is comprehension,” declared a 2020 Fordham Institute study , sounding a note of defiance as it staked out a position in the ongoing debate over the teaching of intrinsic reading skills versus the teaching of content knowledge.

While elementary students spend an enormous amount of time working on skills like “finding the main idea” and “summarizing”—tasks born of the belief that reading is a discrete and trainable ability that transfers seamlessly across content areas—these young readers aren’t experiencing “the additional reading gains that well-intentioned educators hoped for,” the study concluded.

So what works? The researchers looked at data from more than 18,000 K–5 students, focusing on the time spent in subject areas like math, social studies, and ELA, and found that “social studies is the only subject with a clear, positive, and statistically significant effect on reading improvement.” In effect, exposing kids to rich content in civics, history, and law appeared to teach reading more effectively than our current methods of teaching reading. Perhaps defiance is no longer needed: Fordham’s conclusions are rapidly becoming conventional wisdom—and they extend beyond the limited claim of reading social studies texts. According to Natalie Wexler, the author of the well-received 2019 book The Knowledge Gap , content knowledge and reading are intertwined. “Students with more [background] knowledge have a better chance of understanding whatever text they encounter. They’re able to retrieve more information about the topic from long-term memory, leaving more space in working memory for comprehension,” she recently told Edutopia .

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

EVs fight warming but are costly. Why aren’t we driving $10,000 Chinese imports?

Toll of QAnon on families of followers

The urgent message coming from boys

Rubén Rodriguez/Unsplash

Time to fix American education with race-for-space resolve

Harvard Staff Writer

Paul Reville says COVID-19 school closures have turned a spotlight on inequities and other shortcomings

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As former secretary of education for Massachusetts, Paul Reville is keenly aware of the financial and resource disparities between districts, schools, and individual students. The school closings due to coronavirus concerns have turned a spotlight on those problems and how they contribute to educational and income inequality in the nation. The Gazette talked to Reville, the Francis Keppel Professor of Practice of Educational Policy and Administration at Harvard Graduate School of Education , about the effects of the pandemic on schools and how the experience may inspire an overhaul of the American education system.

Paul Reville

GAZETTE: Schools around the country have closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do these massive school closures have any precedent in the history of the United States?

REVILLE: We’ve certainly had school closures in particular jurisdictions after a natural disaster, like in New Orleans after the hurricane. But on this scale? No, certainly not in my lifetime. There were substantial closings in many places during the 1918 Spanish Flu, some as long as four months, but not as widespread as those we’re seeing today. We’re in uncharted territory.

GAZETTE: What lessons did school districts around the country learn from school closures in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and other similar school closings?

REVILLE: I think the lessons we’ve learned are that it’s good [for school districts] to have a backup system, if they can afford it. I was talking recently with folks in a district in New Hampshire where, because of all the snow days they have in the wintertime, they had already developed a backup online learning system. That made the transition, in this period of school closure, a relatively easy one for them to undertake. They moved seamlessly to online instruction.

Most of our big systems don’t have this sort of backup. Now, however, we’re not only going to have to construct a backup to get through this crisis, but we’re going to have to develop new, permanent systems, redesigned to meet the needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis. For example, we have always had large gaps in students’ learning opportunities after school, weekends, and in the summer. Disadvantaged students suffer the consequences of those gaps more than affluent children, who typically have lots of opportunities to fill in those gaps. I’m hoping that we can learn some things through this crisis about online delivery of not only instruction, but an array of opportunities for learning and support. In this way, we can make the most of the crisis to help redesign better systems of education and child development.

GAZETTE: Is that one of the silver linings of this public health crisis?

REVILLE: In politics we say, “Never lose the opportunity of a crisis.” And in this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly. There are things we can learn in the messiness of adapting through this crisis, which has revealed profound disparities in children’s access to support and opportunities. We should be asking: How do we make our school, education, and child-development systems more individually responsive to the needs of our students? Why not construct a system that meets children where they are and gives them what they need inside and outside of school in order to be successful? Let’s take this opportunity to end the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

GAZETTE: How seriously are students going to be set back by not having formal instruction for at least two months, if not more?

“The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling,” Paul Reville said of the current situation. “We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

REVILLE: The first thing to consider is that it’s going to be a variable effect. We tend to regard our school systems uniformly, but actually schools are widely different in their operations and impact on children, just as our students themselves are very different from one another. Children come from very different backgrounds and have very different resources, opportunities, and support outside of school. Now that their entire learning lives, as well as their actual physical lives, are outside of school, those differences and disparities come into vivid view. Some students will be fine during this crisis because they’ll have high-quality learning opportunities, whether it’s formal schooling or informal homeschooling of some kind coupled with various enrichment opportunities. Conversely, other students won’t have access to anything of quality, and as a result will be at an enormous disadvantage. Generally speaking, the most economically challenged in our society will be the most vulnerable in this crisis, and the most advantaged are most likely to survive it without losing too much ground.

GAZETTE: Schools in Massachusetts are closed until May 4. Some people are saying they should remain closed through the end of the school year. What’s your take on this?

REVILLE: That should be a medically based judgment call that will be best made several weeks from now. If there’s evidence to suggest that students and teachers can safely return to school, then I’d say by all means. However, that seems unlikely.

GAZETTE: The digital divide between students has become apparent as schools have increasingly turned to online instruction. What can school systems do to address that gap?

REVILLE: Arguably, this is something that schools should have been doing a long time ago, opening up the whole frontier of out-of-school learning by virtue of making sure that all students have access to the technology and the internet they need in order to be connected in out-of-school hours. Students in certain school districts don’t have those affordances right now because often the school districts don’t have the budget to do this, but federal, state, and local taxpayers are starting to see the imperative for coming together to meet this need.

Twenty-first century learning absolutely requires technology and internet. We can’t leave this to chance or the accident of birth. All of our children should have the technology they need to learn outside of school. Some communities can take it for granted that their children will have such tools. Others who have been unable to afford to level the playing field are now finding ways to step up. Boston, for example, has bought 20,000 Chromebooks and is creating hotspots around the city where children and families can go to get internet access. That’s a great start but, in the long run, I think we can do better than that. At the same time, many communities still need help just to do what Boston has done for its students.

Communities and school districts are going to have to adapt to get students on a level playing field. Otherwise, many students will continue to be at a huge disadvantage. We can see this playing out now as our lower-income and more heterogeneous school districts struggle over whether to proceed with online instruction when not everyone can access it. Shutting down should not be an option. We have to find some middle ground, and that means the state and local school districts are going to have to act urgently and nimbly to fill in the gaps in technology and internet access.

GAZETTE : What can parents can do to help with the homeschooling of their children in the current crisis?

“In this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly.”

More like this

The collective effort

Notes from the new normal

‘If you remain mostly upright, you are doing it well enough’

REVILLE: School districts can be helpful by giving parents guidance about how to constructively use this time. The default in our education system is now homeschooling. Virtually all parents are doing some form of homeschooling, whether they want to or not. And the question is: What resources, support, or capacity do they have to do homeschooling effectively? A lot of parents are struggling with that.

And again, we have widely variable capacity in our families and school systems. Some families have parents home all day, while other parents have to go to work. Some school systems are doing online classes all day long, and the students are fully engaged and have lots of homework, and the parents don’t need to do much. In other cases, there is virtually nothing going on at the school level, and everything falls to the parents. In the meantime, lots of organizations are springing up, offering different kinds of resources such as handbooks and curriculum outlines, while many school systems are coming up with guidance documents to help parents create a positive learning environment in their homes by engaging children in challenging activities so they keep learning.

There are lots of creative things that can be done at home. But the challenge, of course, for parents is that they are contending with working from home, and in other cases, having to leave home to do their jobs. We have to be aware that families are facing myriad challenges right now. If we’re not careful, we risk overloading families. We have to strike a balance between what children need and what families can do, and how you maintain some kind of work-life balance in the home environment. Finally, we must recognize the equity issues in the forced overreliance on homeschooling so that we avoid further disadvantaging the already disadvantaged.

GAZETTE: What has been the biggest surprise for you thus far?

REVILLE: One that’s most striking to me is that because schools are closed, parents and the general public have become more aware than at any time in my memory of the inequities in children’s lives outside of school. Suddenly we see front-page coverage about food deficits, inadequate access to health and mental health, problems with housing stability, and access to educational technology and internet. Those of us in education know these problems have existed forever. What has happened is like a giant tidal wave that came and sucked the water off the ocean floor, revealing all these uncomfortable realities that had been beneath the water from time immemorial. This newfound public awareness of pervasive inequities, I hope, will create a sense of urgency in the public domain. We need to correct for these inequities in order for education to realize its ambitious goals. We need to redesign our systems of child development and education. The most obvious place to start for schools is working on equitable access to educational technology as a way to close the digital-learning gap.

GAZETTE: You’ve talked about some concrete changes that should be considered to level the playing field. But should we be thinking broadly about education in some new way?

REVILLE: The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling. We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives. In order for children to come to school ready to learn, they need a wide array of essential supports and opportunities outside of school. And we haven’t done a very good job of providing these. These education prerequisites go far beyond the purview of school systems, but rather are the responsibility of communities and society at large. In order to learn, children need equal access to health care, food, clean water, stable housing, and out-of-school enrichment opportunities, to name just a few preconditions. We have to reconceptualize the whole job of child development and education, and construct systems that meet children where they are and give them what they need, both inside and outside of school, in order for all of them to have a genuine opportunity to be successful.

Within this coronavirus crisis there is an opportunity to reshape American education. The only precedent in our field was when the Sputnik went up in 1957, and suddenly, Americans became very worried that their educational system wasn’t competitive with that of the Soviet Union. We felt vulnerable, like our defenses were down, like a nation at risk. And we decided to dramatically boost the involvement of the federal government in schooling and to increase and improve our scientific curriculum. We decided to look at education as an important factor in human capital development in this country. Again, in 1983, the report “Nation at Risk” warned of a similar risk: Our education system wasn’t up to the demands of a high-skills/high-knowledge economy.

We tried with our education reforms to build a 21st-century education system, but the results of that movement have been modest. We are still a nation at risk. We need another paradigm shift, where we look at our goals and aspirations for education, which are summed up in phrases like “No Child Left Behind,” “Every Student Succeeds,” and “All Means All,” and figure out how to build a system that has the capacity to deliver on that promise of equity and excellence in education for all of our students, and all means all. We’ve got that opportunity now. I hope we don’t fail to take advantage of it in a misguided rush to restore the status quo.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Share this article

You might like.

Experts say tension between trade, green-tech policies hampers climate change advances; more targeted response needed

New book by Nieman Fellow explores pain, frustration in efforts to help loved ones break free of hold of conspiracy theorists

When we don’t listen, we all suffer, says psychologist whose new book is ‘Rebels with a Cause’

Billions worldwide deficient in essential micronutrients

Inadequate levels carry risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, blindness

You want to be boss. You probably won’t be good at it.

Study pinpoints two measures that predict effective managers

Weight-loss drug linked to fewer COVID deaths

Large-scale study finds Wegovy reduces risk of heart attack, stroke

Quality education an ‘essential pillar’ of a better future, says UN chief

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Education is an “essential pillar” to achieving the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, UN chief António Guterres told an audience on Tuesday at the Paris headquarters of UNESCO, the UN Educational, Scientific and Culture Organization, ahead of the agency’s General Conference .

We must ensure universal access to basic education for every child, everywhere. Tijjani Muhammad-Bande, President, UN General Assembly

Mr. Guterres, who noted that one-fifth of young people are out of work, lack education or adequate training, praised UNESCO ’s fundamental role in coordinating and monitoring global efforts, such as the agency’s initiative on the future of education.

The theme was taken up by Tijjani Muhammad-Bande, President of the UN General Assembly, in his opening remarks to a ministerial meeting on education at the Conference.

Mr. Muhammad-Bande referred to estimates showing that some 265 million children are out of school. The number is projected to fall to 220 million over the next decade, but he declared that the illiteracy figures forecast for 2030 remain a scandal: “We must remove all barriers to education. We must ensure, at a minimum, universal access to basic education for every child, everywhere.”

He also highlighted the importance of educating children effectively, and equipping them with the necessary analytical and critical thinking abilities, in “an ever-changing and more complex world”.

Recalling his former experience as an educator in his home country of Nigeria, Mr. Muhammad-Bande called for more efforts to ensure that teachers are adequately qualified, because “no educational system can rise above the quality of its teachers”.

António Guterres, UN Secretary-General

Other important measures cited by the General Assembly President include strong curricula that fully integrate Information and Communications Technology (ICT); ensuring that girls complete at least 12 years of education (which, according to the World Bank, would add some $30 trillion to the global economy); and the effective monitoring and evaluation of learning.

Mr. Muhammad-Bande called on nations to meet their commitments to education spending, and for donor countries to increase international aid directed towards education.

‘Powerful agents of change’

As well as the difficulties in accessing quality education, Mr. Guterres also outlined several other challenges faced by young people: the fact that millions of girls become mothers while they are still children; that one quarter are affected by violence or conflict; and that online bullying and harassment are adding to high levels of stress, which see some 67,000 adolescents die from suicide or self-harm every year.

World leaders, and others who wield power, he continued, must treat young people not as subjects to be protected, but as powerful agents for change, and the role of the powerful is not to solve the enormous challenges faced by young people, but rather to give them the tools to tackle their problems.

Mr Guterres underscored the importance of bringing young people to the table as key partners, and praised UNESCO’s efforts to include their voices, which include holding a major event at the General Conference, and the Youth Forum .

- quality education

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Is Online Learning Effective?

A new report found that the heavy dependence on technology during the pandemic caused “staggering” education inequality. What was your experience?

By Natalie Proulx

During the coronavirus pandemic, many schools moved classes online. Was your school one of them? If so, what was it like to attend school online? Did you enjoy it? Did it work for you?

In “ Dependence on Tech Caused ‘Staggering’ Education Inequality, U.N. Agency Says ,” Natasha Singer writes:

In early 2020, as the coronavirus spread, schools around the world abruptly halted in-person education. To many governments and parents, moving classes online seemed the obvious stopgap solution. In the United States, school districts scrambled to secure digital devices for students. Almost overnight, videoconferencing software like Zoom became the main platform teachers used to deliver real-time instruction to students at home. Now a report from UNESCO , the United Nations’ educational and cultural organization, says that overreliance on remote learning technology during the pandemic led to “staggering” education inequality around the world. It was, according to a 655-page report that UNESCO released on Wednesday, a worldwide “ed-tech tragedy.” The report, from UNESCO’s Future of Education division, is likely to add fuel to the debate over how governments and local school districts handled pandemic restrictions, and whether it would have been better for some countries to reopen schools for in-person instruction sooner. The UNESCO researchers argued in the report that “unprecedented” dependence on technology — intended to ensure that children could continue their schooling — worsened disparities and learning loss for hundreds of millions of students around the world, including in Kenya, Brazil, Britain and the United States. The promotion of remote online learning as the primary solution for pandemic schooling also hindered public discussion of more equitable, lower-tech alternatives, such as regularly providing schoolwork packets for every student, delivering school lessons by radio or television — and reopening schools sooner for in-person classes, the researchers said. “Available evidence strongly indicates that the bright spots of the ed-tech experiences during the pandemic, while important and deserving of attention, were vastly eclipsed by failure,” the UNESCO report said. The UNESCO researchers recommended that education officials prioritize in-person instruction with teachers, not online platforms, as the primary driver of student learning. And they encouraged schools to ensure that emerging technologies like A.I. chatbots concretely benefited students before introducing them for educational use. Education and industry experts welcomed the report, saying more research on the effects of pandemic learning was needed. “The report’s conclusion — that societies must be vigilant about the ways digital tools are reshaping education — is incredibly important,” said Paul Lekas, the head of global public policy for the Software & Information Industry Association, a group whose members include Amazon, Apple and Google. “There are lots of lessons that can be learned from how digital education occurred during the pandemic and ways in which to lessen the digital divide. ” Jean-Claude Brizard, the chief executive of Digital Promise, a nonprofit education group that has received funding from Google, HP and Verizon, acknowledged that “technology is not a cure-all.” But he also said that while school systems were largely unprepared for the pandemic, online education tools helped foster “more individualized, enhanced learning experiences as schools shifted to virtual classrooms.” Education International, an umbrella organization for about 380 teachers’ unions and 32 million teachers worldwide, said the UNESCO report underlined the importance of in-person, face-to-face teaching. “The report tells us definitively what we already know to be true, a place called school matters,” said Haldis Holst, the group’s deputy general secretary. “Education is not transactional nor is it simply content delivery. It is relational. It is social. It is human at its core.”

Students, read the entire article and then tell us:

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea karyn lewis , and karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).

Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were 0.20-0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09-0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees .

Even more concerning, test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math (corresponding to 0.20 SDs) and 15% in reading (0.13 SDs), primarily during the 2020-21 school year. Further, achievement tended to drop more between fall 2020 and 2021 than between fall 2019 and 2020 (both overall and differentially by school poverty), indicating that disruptions to learning have continued to negatively impact students well past the initial hits following the spring 2020 school closures.