- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early life and works

- The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

- Other projects

- The Medici Chapel

- The Laurentian Library and fortifications

- Other projects and writing

- The last decades

- Legacy and influence

What is Michelangelo best known for?

Why is michelangelo so famous, how did michelangelo paint the ceiling of the sistine chapel, what was michelangelo like as a person, what makes michelangelo a renaissance man.

Michelangelo

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Digital Commons at Lindenwood University - Michelangelo's Last Judgement: A crisis of conscience

- Official Site of Michelangelo

- Art in Context - Biography of Michelangelo Buonarroti

- The Art Story - Biography of Michelangelo

- World History Encyclopedia - Michelangelo

- Web Gallery of Art - Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Smart History - Who was Michelangelo?

- Michelangelo - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Michelangelo - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

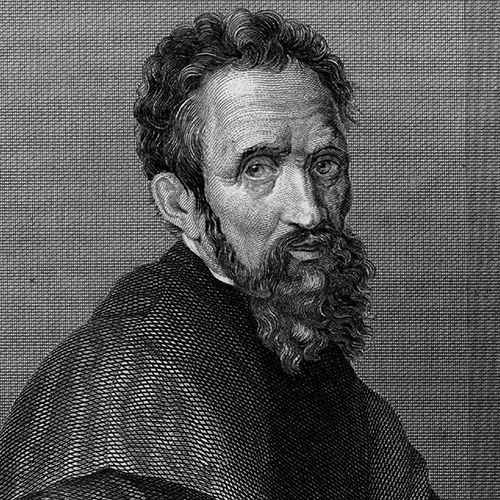

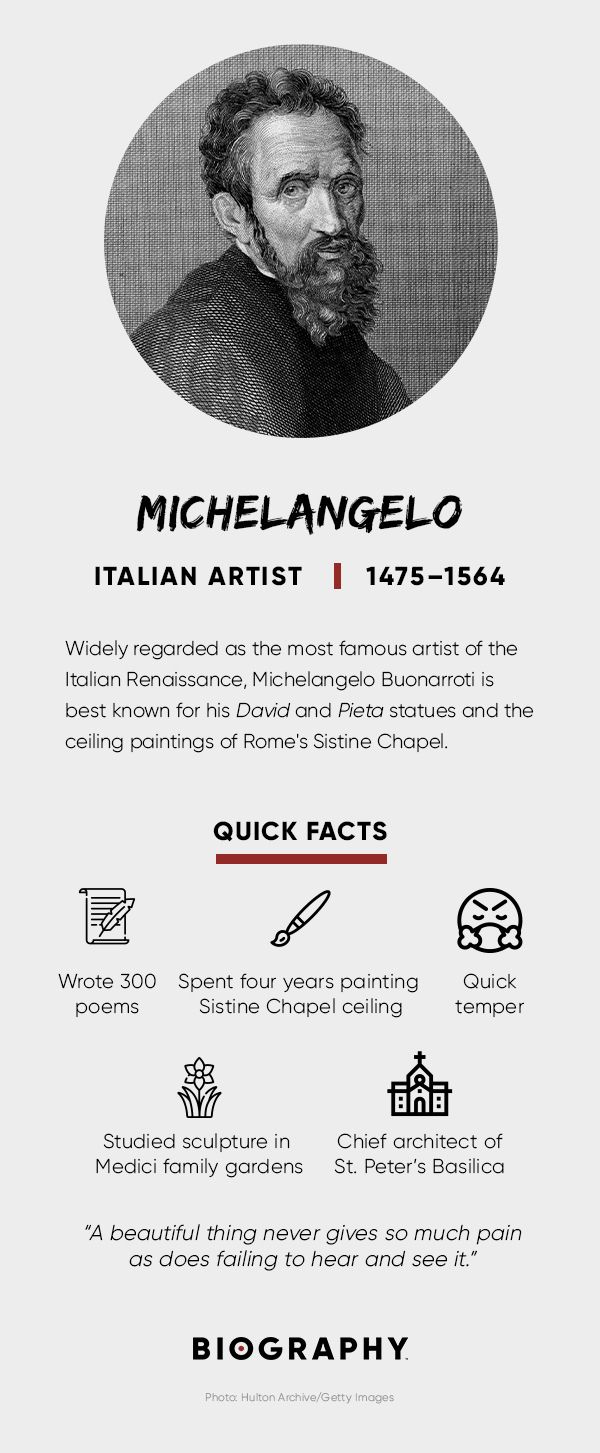

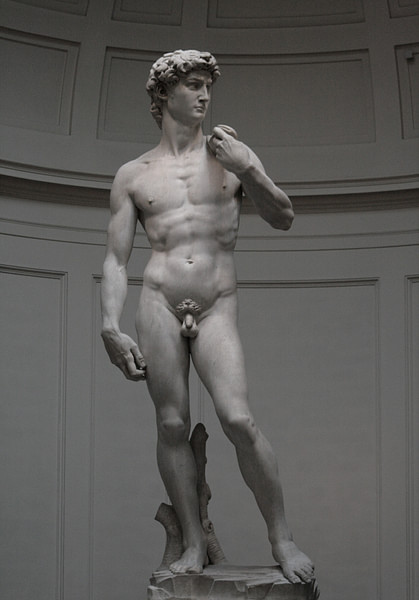

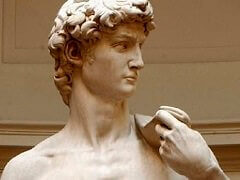

The frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508–12) in the Vatican , which include the iconic depiction of the creation of Adam interpreted from Genesis , are probably the best known of Michelangelo’s works today, but the artist thought of himself primarily as a sculptor. His famed sculptures include the David (1501), now in the Accademia in Florence, and the Pietà (1499), now in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

Michelangelo first gained notice in his 20s for his sculptures of the Pietà (1499) and David (1501) and cemented his fame with the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel (1508–12). He was celebrated for his art’s complexity, physical realism, psychological tension, and thoughtful consideration of space, light, and shadow. Many writers have commented on his ability to turn stone into flesh and to imbue his painted figures with energy. Michelangelo’s talent continued to be recognized in subsequent centuries, and thus his fame has endured into the 21st century.

Michelangelo painted the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel not lying down as sometimes described but standing on an extensive scaffold, reaching up and craning his neck. Because he had never worked in fresco before, Michelangelo and his assistants worked from hundreds of his sketches to transfer outlines onto a freshly plastered surface. Once he became comfortable with the medium, however, he abandoned the sketches. To add colour, Michelangelo used the buon fresco technique, in which the artist paints quickly on wet plaster before it dries. Some scholars believe that for detailed work, such as a figure’s face, Michelangelo probably used the fresco secco technique, in which the artist paints on a dry plaster surface.

Many writers have described Michelangelo as the archetype of a brooding and difficult artist, and, although he was indeed hot-tempered, his character was much more complex than the sullen artist stereotype. He was also deeply religious and could be very generous toward his assistants. There has been some speculation that Michelangelo might have been gay, but scholars cannot confirm his sexual preference. He led a mostly solitary life with few known intimate relationships.

The Renaissance man is an ideal that developed in Renaissance Italy from one of its most-accomplished representatives, Leon Battista Alberti , who stated that “a man can do all things if he will.” This led to the notion that men should try to embrace all knowledge and develop their own capacities as fully as possible, and thus gifted men of the Renaissance sought to develop skills in all areas of knowledge, in physical development, in social accomplishments, and in the arts. Michelangelo exemplified the ideal through his accomplishments in sculpture , painting , architecture , and poetry .

Michelangelo (born March 6, 1475, Caprese, Republic of Florence [Italy]—died February 18, 1564, Rome , Papal States) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor, painter, architect, and poet who exerted an unparalleled influence on the development of Western art.

Michelangelo was considered the greatest living artist in his lifetime, and ever since then he has been held to be one of the greatest artists of all time. A number of his works in painting , sculpture , and architecture rank among the most famous in existence. Although the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (Vatican; see below ) are probably the best known of his works, the artist thought of himself primarily as a sculptor. His practice of several arts, however, was not unusual in his time, when all of them were thought of as based on design, or drawing . Michelangelo worked in marble sculpture all his life and in the other arts only during certain periods. The high regard for the Sistine ceiling is partly a reflection of the greater attention paid to painting in the 20th century and partly, too, because many of the artist’s works in other media remain unfinished.

A side effect of Michelangelo’s fame in his lifetime was that his career was more fully documented than that of any artist of the time or earlier. He was the first Western artist whose biography was published while he was alive—in fact, there were two rival biographies. The first was the final chapter in the series of artists’ lives (1550) by the painter and architect Giorgio Vasari . It was the only chapter on a living artist and explicitly presented Michelangelo’s works as the culminating perfection of art, surpassing the efforts of all those before him. Despite such an encomium, Michelangelo was not entirely pleased and arranged for his assistant Ascanio Condivi to write a brief separate book (1553); probably based on the artist’s own spoken comments, this account shows him as he wished to appear. After Michelangelo’s death, Vasari in a second edition (1568) offered a rebuttal. While scholars have often preferred the authority of Condivi, Vasari’s lively writing, the importance of his book as a whole, and its frequent reprinting in many languages have made it the most usual basis of popular ideas on Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists. Michelangelo’s fame also led to the preservation of countless mementos, including hundreds of letters, sketches, and poems, again more than of any contemporary. Yet despite the enormous benefit that has accrued from all this, in controversial matters often only Michelangelo’s side of an argument is known.

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born to a family that had for several generations belonged to minor nobility in Florence but had, by the time the artist was born, lost its patrimony and status. His father had only occasional government jobs, and at the time of Michelangelo’s birth he was administrator of the small dependent town of Caprese. A few months later, however, the family returned to its permanent residence in Florence. It was something of a downward social step to become an artist, and Michelangelo became an apprentice relatively late, at 13, perhaps after overcoming his father’s objections. He was apprenticed to the city’s most prominent painter, Domenico Ghirlandaio , for a three-year term, but he left after one year, having (Condivi recounts) nothing more to learn. Several drawings, copies of figures by Ghirlandaio and older great painters of Florence, Giotto and Masaccio , survive from this stage; such copying was standard for apprentices, but few examples are known to survive. Obviously talented, he was taken under the wing of the ruler of the city, Lorenzo de’ Medici , known as the Magnificent. Lorenzo surrounded himself with poets and intellectuals , and Michelangelo was included. More important, he had access to the Medici art collection , which was dominated by fragments of ancient Roman statuary. (Lorenzo was not such a patron of contemporary art as legend has made him; such modern art as he owned was to ornament his house or to make political statements.) The bronze sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni , a Medici friend who was in charge of the collection, was the nearest he had to a teacher of sculpture, but Michelangelo did not follow his medium or in any major way his approach. Still, one of the two marble works that survive from the artist’s first years is a variation on the composition of an ancient Roman sarcophagus , and Bertoldo had produced a similar one in bronze. This composition is the Battle of the Centaurs (c. 1492). The action and power of the figures foretell the artist’s later interests much more than does the Madonna of the Stairs (c. 1491), a delicate low relief that reflects recent fashions among such Florentine sculptors as Desiderio da Settignano .

Florence was at this time regarded as the leading centre of art, producing the best painters and sculptors in Europe, and the competition among artists was stimulating. The city was, however, less able than earlier to offer large commissions, and leading Florentine-born artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Leonardo’s teacher, Andrea del Verrocchio , had moved away for better opportunities in other cities. The Medici were overthrown in 1494, and even before the end of the political turmoil Michelangelo had left.

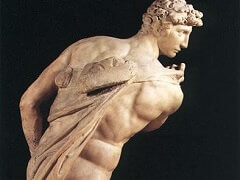

In Bologna he was hired to succeed a recently deceased sculptor and carve the last small figures required to complete a grand project, the tomb and shrine of St. Dominic (1494–95). The three marble figures are original and expressive. Departing from his predecessor’s fanciful agility, he imposed seriousness on his images by a compactness of form that owed much to Classical antiquity and to the Florentine tradition from Giotto onward. This emphasis on seriousness is also reflected in his choice of marble as his medium, while the accompanying simplification of masses is in contrast to the then more usual tendency to let representations match as completely as possible the texture and detail of human bodies. To be sure, although these are constant qualities in Michelangelo’s art, they often are temporarily abandoned or modified because of other factors, such as the specific functions of works or the stimulating creations of other artists. This is the case with Michelangelo’s first surviving large statue, the Bacchus , produced in Rome (1496–97) following a brief return to Florence. (A wooden crucifix, recently discovered, attributed by some scholars to Michelangelo and now housed in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, has also been proposed as the antecedent of the Bacchus in design by those who credit it as the artist’s work.) The Bacchus relies on ancient Roman nude figures as a point of departure, but it is much more mobile and more complex in outline. The conscious instability evokes the god of wine and Dionysian revels with extraordinary virtuosity. Made for a garden, it is also unique among Michelangelo’s works in calling for observation from all sides rather than primarily from the front.

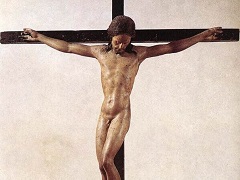

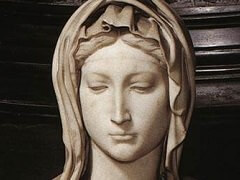

The Bacchus led at once to the commission (1498) for the Pietà , now in St. Peter’s Basilica . The name refers not (as is often presumed) to this specific work but to a common traditional type of devotional image, this work being today the most famous example. Extracted from narrative scenes of the lamentation after Christ’s death, the concentrated group of two is designed to evoke the observer’s repentant prayers for sins that required Christ’s sacrificial death. The patron was a French cardinal, and the type was earlier more common in northern Europe than in Italy . The complex problem for the designer was to extract two figures from one marble block, an unusual undertaking in all periods. Michelangelo treated the group as one dense and compact mass as before so that it has an imposing impact, yet he underlined the many contrasts present—of male and female, vertical and horizontal, clothed and naked, dead and alive—to clarify the two components.

The artist’s prominence, established by this work, was reinforced at once by the commission (1501) of the David for the cathedral of Florence. For this huge statue, an exceptionally large commission in that city, Michelangelo reused a block left unfinished about 40 years before. The modeling is especially close to the formulas of classical antiquity, with a simplified geometry suitable to the huge scale yet with a mild assertion of organic life in its asymmetry. It has continued to serve as the prime statement of the Renaissance ideal of perfect humanity. Although the sculpture was originally intended for the buttress of the cathedral, the magnificence of the finished work convinced Michelangelo’s contemporaries to install it in a more prominent place, to be determined by a commission formed of artists and prominent citizens. They decided that the David would be installed in front of the entrance of the Palazzo dei Priori (now called Palazzo Vecchio) as a symbol of the Florentine Republic. It was later replaced by a copy, and the original was moved to the Galleria dell’Accademia .

On the side Michelangelo produced in the same years (1501–04) several Madonnas for private houses, the staple of artists’ work at the time. These include one small statue, two circular reliefs that are similar to paintings in suggesting varied levels of spatial depth, and the artist’s only easel painting . While the statue ( Madonna and Child ) is blocky and immobile, the painting ( Holy Family ) and one of the reliefs ( Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John ) are full of motion; they show arms and legs of figures interweaving in actions that imply movement through time. The forms carry symbolic references to Christ’s future death, common in images of the Christ Child at the time; they also betray the artist’s fascination with the work of Leonardo . Michelangelo regularly denied that anyone influenced him, and his statements have usually been accepted without demur. But Leonardo’s return to Florence in 1500 after nearly 20 years was exciting to younger artists there, and later scholars generally agreed that Michelangelo was among those affected. Leonardo’s works were probably the most powerful and lasting outside influence to modify Michelangelo’s work, and he was able to blend Leonardo’s ability to show momentary processes with his own to suggest weight and strength, without losing any of the latter quality. The resulting images, of massive bodies in forceful action, are those special creations that constitute the larger part of his most admired major works.

The Holy Family , probably commissioned for the birth of the first child of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni, was a particularly innovative painting that would later be influential in the development of early Florentine Mannerism . Its spiraling composition and cold, brilliant colour scheme underline the sculptural intensity of the figures and create a dynamic and expressive effect. The iconographic interpretation has caused countless scholarly debates, which to the present day have not been entirely resolved.

Michelangelo

Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

(1475-1564)

Who Was Michelangelo?

Michelangelo Buonarroti was a painter, sculptor, architect and poet widely considered one of the most brilliant artists of the Italian Renaissance . Michelangelo was an apprentice to a painter before studying in the sculpture gardens of the powerful Medici family .

What followed was a remarkable career as an artist, famed in his own time for his artistic virtuosity. Although he always considered himself a Florentine, Michelangelo lived most of his life in Rome, where he died at age 88.

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, the second of five sons.

When Michelangelo was born, his father, Leonardo di Buonarrota Simoni, was briefly serving as a magistrate in the small village of Caprese. The family returned to Florence when Michelangelo was still an infant.

His mother, Francesca Neri, was ill, so Michelangelo was placed with a family of stonecutters, where he later jested, "With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues."

Indeed, Michelangelo was less interested in schooling than watching the painters at nearby churches and drawing what he saw, according to his earliest biographers (Vasari, Condivi and Varchi). It may have been his grammar school friend, Francesco Granacci, six years his senior, who introduced Michelangelo to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Michelangelo's father realized early on that his son had no interest in the family financial business, so he agreed to apprentice him, at the age of 13, to Ghirlandaio and the Florentine painter's fashionable workshop. There, Michelangelo was exposed to the technique of fresco (a mural painting technique where pigment is placed directly on fresh, or wet, lime plaster).

Medici Family

From 1489 to 1492, Michelangelo studied classical sculpture in the palace gardens of Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici of the powerful Medici family. This extraordinary opportunity opened to him after spending only a year at Ghirlandaio’s workshop, at his mentor’s recommendation.

This was a fertile time for Michelangelo; his years with the family permitted him access to the social elite of Florence — allowing him to study under the respected sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni and exposing him to prominent poets, scholars and learned humanists.

He also obtained special permission from the Catholic Church to study cadavers for insight into anatomy, though exposure to corpses had an adverse effect on his health.

These combined influences laid the groundwork for what would become Michelangelo's distinctive style: a muscular precision and reality combined with an almost lyrical beauty. Two relief sculptures that survive, "Battle of the Centaurs" and "Madonna Seated on a Step," are testaments to his phenomenal talent at the tender age of 16.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MICHELANGELO FACT CARD

Move to Rome

Political strife in the aftermath of Lorenzo de' Medici’s death led Michelangelo to flee to Bologna, where he continued his study. He returned to Florence in 1495 to begin work as a sculptor, modeling his style after masterpieces of classical antiquity.

There are several versions of an intriguing story about Michelangelo's famed "Cupid" sculpture, which was artificially "aged" to resemble a rare antique: One version claims that Michelangelo aged the statue to achieve a certain patina, and another version claims that his art dealer buried the sculpture (an "aging" method) before attempting to pass it off as an antique.

Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio bought the "Cupid" sculpture, believing it as such, and demanded his money back when he discovered he'd been duped. Strangely, in the end, Riario was so impressed with Michelangelo's work that he let the artist keep the money. The cardinal even invited the artist to Rome, where Michelangelo would live and work for the rest of his life.

Personality

Though Michelangelo's brilliant mind and copious talents earned him the regard and patronage of the wealthy and powerful men of Italy, he had his share of detractors.

He had a contentious personality and quick temper, which led to fractious relationships, often with his superiors. This not only got Michelangelo into trouble, it created a pervasive dissatisfaction for the painter, who constantly strived for perfection but was unable to compromise.

He sometimes fell into spells of melancholy, which were recorded in many of his literary works: "I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts," he once wrote.

In his youth, Michelangelo had taunted a fellow student, and received a blow on the nose that disfigured him for life. Over the years, he suffered increasing infirmities from the rigors of his work; in one of his poems, he documented the tremendous physical strain that he endured by painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Political strife in his beloved Florence also gnawed at him, but his most notable enmity was with fellow Florentine artist Leonardo da Vinci , who was more than 20 years his senior.

Poetry and Personal Life

Michelangelo's poetic impulse, which had been expressed in his sculptures, paintings and architecture, began taking literary form in his later years.

Although he never married, Michelangelo was devoted to a pious and noble widow named Vittoria Colonna, the subject and recipient of many of his more than 300 poems and sonnets. Their friendship remained a great solace to Michelangelo until Colonna's death in 1547.

Soon after Michelangelo's move to Rome in 1498, the cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, a representative of the French King Charles VIII to the pope, commissioned "Pieta," a sculpture of Mary holding the dead Jesus across her lap.

Michelangelo, who was just 25 years old at the time, finished his work in less than one year, and the statue was erected in the church of the cardinal's tomb. At 6 feet wide and nearly as tall, the statue has been moved five times since, to its present place of prominence at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.

Carved from a single piece of Carrara marble, the fluidity of the fabric, positions of the subjects, and "movement" of the skin of the Piet — meaning "pity" or "compassion" — created awe for its early viewers, as it does even today.

It is the only work to bear Michelangelo’s name: Legend has it that he overheard pilgrims attribute the work to another sculptor, so he boldly carved his signature in the sash across Mary's chest. Today, the "Pieta" remains a universally revered work.

Between 1501 and 1504, Michelangelo took over a commission for a statue of "David," which two prior sculptors had previously attempted and abandoned, and turned the 17-foot piece of marble into a dominating figure.

The strength of the statue's sinews, vulnerability of its nakedness, humanity of expression and overall courage made the "David" a highly prized representative of the city of Florence.

Originally commissioned for the cathedral of Florence, the Florentine government instead installed the statue in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. It now lives in Florence’s Accademia Gallery .

Sistine Chapel

Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to switch from sculpting to painting to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which the artist revealed on October 31, 1512. The project fueled Michelangelo’s imagination, and the original plan for 12 apostles morphed into more than 300 figures on the ceiling of the sacred space. (The work later had to be completely removed soon after due to an infectious fungus in the plaster, then recreated.)

Michelangelo fired all of his assistants, whom he deemed inept, and completed the 65-foot ceiling alone, spending endless hours on his back and guarding the project jealously until completion.

The resulting masterpiece is a transcendent example of High Renaissance art incorporating the symbology, prophecy and humanist principles of Christianity that Michelangelo had absorbed during his youth.

'Creation of Adam'

The vivid vignettes of Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling produce a kaleidoscope effect, with the most iconic image being the " Creation of Adam," a famous portrayal of God reaching down to touch the finger of man.

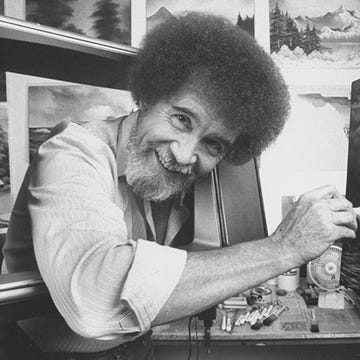

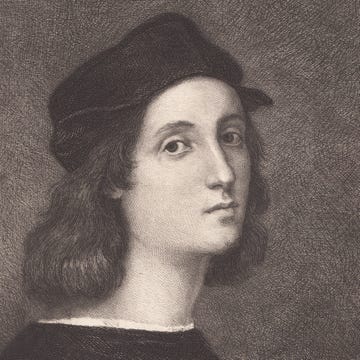

Rival Roman painter Raphael evidently altered his style after seeing the work.

'Last Judgment'

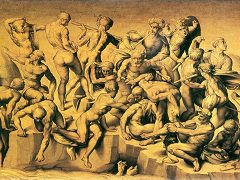

Michelangelo unveiled the soaring "Last Judgment" on the far wall of the Sistine Chapel in 1541. There was an immediate outcry that the nude figures were inappropriate for so holy a place, and a letter called for the destruction of the Renaissance's largest fresco.

The painter retaliated by inserting into the work new portrayals: his chief critic as a devil and himself as the flayed St. Bartholomew.

Architecture

Although Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint throughout his life, following the physical rigor of painting the Sistine Chapel he turned his focus toward architecture.

He continued to work on the tomb of Julius II, which the pope had interrupted for his Sistine Chapel commission, for the next several decades. Michelangelo also designed the Medici Chapel and the Laurentian Library — located opposite the Basilica San Lorenzo in Florence — to house the Medici book collection. These buildings are considered a turning point in architectural history.

But Michelangelo's crowning glory in this field came when he was made chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica in 1546.

Was Michelangelo Gay?

In 1532, Michelangelo developed an attachment to a young nobleman, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, and wrote dozens of romantic sonnets dedicated to Cavalieri.

Despite this, scholars dispute whether this was a platonic or a homosexual relationship.

Michelangelo died on February 18, 1564 — just weeks before his 89th birthday — at his home in Macel de'Corvi, Rome, following a brief illness.

A nephew bore his body back to Florence, where he was revered by the public as the "father and master of all the arts." He was laid to rest at the Basilica di Santa Croce — his chosen place of burial.

Unlike many artists, Michelangelo achieved fame and wealth during his lifetime. He also had the peculiar distinction of living to see the publication of two biographies about his life, written by Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi.

Appreciation of Michelangelo's artistic mastery has endured for centuries, and his name has become synonymous with the finest humanist tradition of the Renaissance.

Watch "Michelangelo: Artist and Man" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Birth Year: 1475

- Birth date: March 6, 1475

- Birth City: Caprese (Republic of Florence)

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Michelangelo was just 25 years old at the time when he created the 'Pieta' statue.

- For the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo fired all of his assistants and painted the 65-foot ceiling alone.

- Despite his immense talent, Michelangelo had a quick temper and contempt for authority.

- Death Year: 1564

- Death date: February 18, 1564

- Death City: Rome

- Death Country: Italy

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Michelangelo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/michelangelo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 4, 2020

- Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

- I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

- I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts.

- With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues.

- A beautiful thing never gives so much pain as does failing to hear and see it.

- Faith in oneself is the best and safest course.

- If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn't seem so wonderful at all.

- Critique by creating.

- The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- With few words I will make thee understand my soul.

- Lord, make me see thy glory in every place.

- Genius is eternal patience.

- If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn't call it genius.

Famous Painters

Frida Kahlo

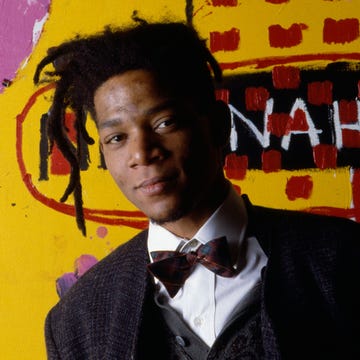

Jean-Michel Basquiat

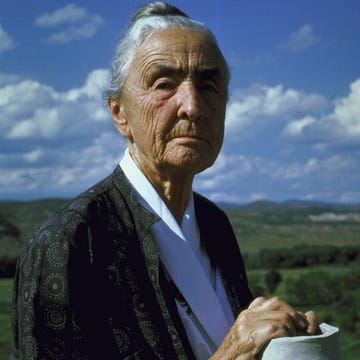

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Michelangelo

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 6, 2019 | Original: October 18, 2010

Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter and architect widely considered to be one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance—and arguably of all time. His work demonstrated a blend of psychological insight, physical realism and intensity never before seen. His contemporaries recognized his extraordinary talent, and Michelangelo received commissions from some of the most wealthy and powerful men of his day, including popes and others affiliated with the Catholic Church. His resulting work, most notably his Pietà and David sculptures and his Sistine Chapel paintings, has been carefully tended and preserved, ensuring that future generations would be able to view and appreciate Michelangelo’s genius.

Early Life and Training

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni) was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy. His father worked for the Florentine government, and shortly after his birth his family returned to Florence, the city Michelangelo would always consider his true home.

Did you know? Michelangelo received the commission to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling as a consolation prize of sorts when Pope Julius II temporarily scaled back plans for a massive sculpted memorial to himself that Michelangelo was to complete.

Florence during the Italian Renaissance period was a vibrant arts center, an opportune locale for Michelangelo’s innate talents to develop and flourish. His mother died when he was 6, and initially his father initially did not approve of his son’s interest in art as a career.

At 13, Michelangelo was apprenticed to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, particularly known for his murals. A year later, his talent drew the attention of Florence’s leading citizen and art patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici , who enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of being surrounded by the city’s most literate, poetic and talented men. He extended an invitation to Michelangelo to reside in a room of his palatial home.

Michelangelo learned from and was inspired by the scholars and writers in Lorenzo’s intellectual circle, and his later work would forever be informed by what he learned about philosophy and politics in those years. While staying in the Medici home, he also refined his technique under the tutelage of Bertoldo di Giovanni, keeper of Lorenzo’s collection of ancient Roman sculptures and a noted sculptor himself. Although Michelangelo expressed his genius in many media, he would always consider himself a sculptor first.

Sculptures: The Pieta and David

Michelangelo was working in Rome by 1498 when he received a career-making commission from the visiting French cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, envoy of King Charles VIII to the pope. The cardinal wanted to create a substantial statue depicting a draped Virgin Mary with her dead son resting in her arms—a Pieta—to grace his own future tomb. Michelangelo’s delicate 69-inch-tall masterpiece featuring two intricate figures carved from one block of marble continues to draw legions of visitors to St. Peter’s Basilica more than 500 years after its completion.

Michelangelo returned to Florence and in 1501 was contracted to create, again from marble, a huge male figure to enhance the city’s famous Duomo, officially the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. He chose to depict the young David from the Old Testament of the Bible as heroic, energetic, powerful and spiritual and literally larger than life at 17 feet tall. The sculpture, considered by scholars to be nearly technically perfect, remains in Florence at the Galleria dell’Accademia , where it is a world-renowned symbol of the city and its artistic heritage.

Paintings: Sistine Chapel

In 1505, Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to sculpt a grand tomb with 40 life-size statues, and the artist began work. But the pope’s priorities shifted away from the project as he became embroiled in military disputes and his funds became scarce, and a displeased Michelangelo left Rome (although he continued to work on the tomb, off and on, for decades).

However, in 1508, Julius called Michelangelo back to Rome for a less expensive, but still ambitious painting project: to depict the 12 apostles on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel , a most sacred part of the Vatican where new popes are elected and inaugurated.

Instead, over the course of the four-year project, Michelangelo painted 12 figures—seven prophets and five sibyls (female prophets of myth)—around the border of the ceiling and filled the central space with scenes from Genesis.

Critics suggest that the way Michelangelo depicts the prophet Ezekiel—as strong yet stressed, determined yet unsure—is symbolic of Michelangelo’s sensitivity to the intrinsic complexity of the human condition. The most famous Sistine Chapel ceiling painting is the emotion-infused The Creation of Adam, in which God and Adam outstretch their hands to one another.

Architecture & Poems

The quintessential Renaissance man, Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint until his death, although he increasingly worked on architectural projects as he aged: His work from 1520 to 1527 on the interior of the Medici Chapel in Florence included wall designs, windows and cornices that were unusual in their design and introduced startling variations on classical forms.

Michelangelo also designed the iconic dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (although its completion came after his death). Among his other masterpieces are Moses (sculpture, completed 1515); The Last Judgment (painting, completed 1534); and Day, Night, Dawn and Dusk (sculptures, all completed by 1533).

Later Years

From the 1530s on, Michelangelo wrote poems; about 300 survive. Many incorporate the philosophy of Neo-Platonism—that a human soul, powered by love and ecstasy, can reunite with an almighty God—ideas that had been the subject of intense discussion while he was an adolescent living in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s household.

After he left Florence permanently in 1534 for Rome, Michelangelo also wrote many lyrical letters to his family members who remained there. The theme of many was his strong attachment to various young men, especially aristocrat Tommaso Cavalieri. Scholars debate whether this was more an expression of homosexuality or a bittersweet longing by the unmarried, childless, aging Michelangelo for a father-son relationship.

Michelangelo died at age 88 after a short illness in 1564, surviving far past the usual life expectancy of the era. A pieta he had begun sculpting in the late 1540s, intended for his own tomb, remained unfinished but is on display at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence—not very far from where Michelangelo is buried, at the Basilica di Santa Croce .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Michelangelo

Michelangelo was known as il divino , (in English, “the divine one”) and it is easy for us to see why.

Learn about some of the materials and techniques Michelangelo employed.

- Quarrying and carving marble

- Carving marble with traditional tools

- Almost Invisible: The Cartoon Transfer Process

videos + essays

Replicating michelangelo.

Replicas form a vital component of Michelangelo’s legacy, and they have helped transform him into a global cultural icon

Can stone be that soft? Contrast defines this sculpture. Mary is sweet but strong, and Christ, real yet ideal.

Where’s Goliath? David scans for his enemy. This colossal sculpture is itself a giant of 16th-century Renaissance art.

The many meanings of Michelangelo's David

Location, location, location. Meant for the cathedral, David presided over a public square—and now stands inside.

Unfinished business—Michelangelo and the Pope

Michelangelo left many sculptures unfinished, but perhaps none are more beautiful than The Prisoners .

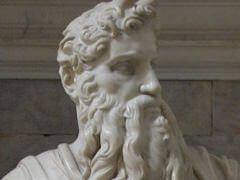

The Hebrew prophet at the center of this tomb exudes energy and power, from his intense gaze to his twisted pose.

Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

God created the world in seven days, but it took Michelangelo four years to depict it on this remarkable ceiling.

Studies for the Libyan Sibyl

Michelangelo transforms a male model into a female figure. Discover the artist’s working process.

Slaves for the Tomb of Pope Julius II

Bound to rock, these figures struggle to escape their marble prisons. One closes his eyes; the other looks to God.

Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel

As demons harvest new souls and angels wake the dead, Mary crouches, powerless beside Christ.

Medici Chapel (New Sacristy)

Night and day, rough and polish—this chapel embodies opposition and traps the viewer in a moment of transition.

Laurentian Library

Michelangelo turns book learning on its head. Defying classical grammar, he speaks his own architectural language.

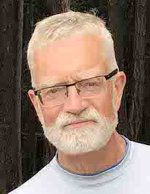

Attributed to Daniele da Volterra, Michelangelo Buonarroti , c. 1545, oil on wood, 88.3 x 64.1 cm ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art )

“Who was Michelangelo?”

Essay by Dr. Tamara Smithers

Michelangelo Buonarotti—the Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, and poet—was called “Il Divino” (The Divine One) by his contemporaries because they perceived his artworks to be otherworldly. His art was in high demand, and thought to have terribilità , poorly translated as “terribleness” and better described as powerfulness. He was mythologized by followers, emulated by artists, celebrated by humanists, and patronized by a total of nine popes. As commemorations, over one hundred portraits of him were created during the sixteenth century alone, far more than any other artist at the time. Despite three biographies written about the artist during his own lifetime, we know the most about the sometimes-generous and often-humorous perfectionist through his letters. Not only do we have more primary sources on Michelangelo than any other historical artist, he is one of the most written-about artists of all time. In today’s terms, Michelangelo was a workaholic homebody whose cats missed him when he was away. He did not like to debate art, waste time, or show his work before he was ready. Despite a few mid-career collaborations, Michelangelo was careful and guarded, never running a typical workshop, locking his studio, and burning drawings. He also complained a lot, and, at times, could be overconfident, curt, and blunt, once resulting in a punch in the nose.

Better late than never

Although he became an artistic superstar, Michelangelo’s start was different from most artists of his time. His initial success can be credited to his family’s connections to the powerful, noble Florentine family, the Medici. In the early 1490s, he learned carving under the tutelage of a student of Donatello , Bertoldo di Giovanni, at the Medici sculpture garden. Upon entering the workshop of the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio , Michelangelo began his official professional training at the age of thirteen, several years later than usual (and unlike typical apprentices who had to pay to study under a master, Michelangelo was paid, perhaps due to his family’s relations to the Medici or his innate talent). However, he desired to sculpt instead, stating that he drank in his love of stone carving from his wet nurse , who came from a family of simple pastoral stonecutters.[1] To emphasize this aspect of himself for the first few decades of his career, he signed his letters “Michelangelo Sculptor.” Also important to his formative years was the dissection of cadavers to learn anatomy. The challenging conditions—after hours by candlelight and without refrigeration—called to only the most dedicated artists.

Michelangelo, Pietà , marble, 1498–1500 (Saint Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Photo: Stanislav Traykov , CC BY 2.5)

At twenty-three years old, Michelangelo accepted his first large-scale public project: to carve two full-scale figures within one piece of stone, a very difficult task. St. Peter’s Pietà , commissioned for the tomb of Cardinal Bilhères de Lagraulas, initiated his rise to fame. The pressure was on: the contract stated that the sculpture was to be the most beautiful work in Rome. After six months at the quarries to find the perfect marble, Michelangelo began carving the Pietà . When the sculpture was put on display in Old St. Peter’s Basilica (before the rebuilding initiated by Pope Julius II), pilgrims questioned who had made such a beautiful work. As the story goes, the sculptor overheard a group incorrectly attribute the work to another sculptor. Michelangelo snuck back in late that night with a lantern, hammer, and chisel to carve his name on the Virgin’s sash. It is the only work he ever signed, and he later regretted this act of excessive pride.

Already famous

Michelangelo, David , marble, 1501–04 (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence)

Soon after, Michelangelo received an important commission in Florence. A figure of David was desired for up high on an outside buttress of the Duomo . He was tasked to re-use a nearly twenty-foot tall piece of marble nicknamed “The White Giant” that another artist had attempted but failed to carve forty years prior. Michelangelo stepped up to the challenge, completing the colossal statue in two years. In the end, the sculpture was placed outside the Palazzo Signoria .

The success of David led to a large-scale civic commission inside the palazzo to paint a battle scene for the Florentine government, the Battle of Cascina . This arrangement placed him in direct competition with Leonardo , who was already at work on the Battle of Anghiari on the opposite wall. While neither painting was ever finished, copies of both survive. Michelangelo’s cartoon (a full-scale preparatory drawing for the fresco), served as a sort of art school for younger artists who came to copy his figures. His drawings from this period are some of his most superbly rendered figures, with a distinct cross-hatching chiaroscuro technique. Disegno , or drawing, was considered both a manual pursuit and an intellectual endeavor and was the most important part of his practice. Sketching from the male nude was central to his art making.

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (detail), 1508–12 (Vatican, Rome)

In his next major fresco project, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel commissioned by Pope Julius II , the main narrative represents nine stories of the Book of Genesis, such as the Creation of Adam . Michelangelo’s bulky, muscular figures were inspired by the ancient Laocoön , which he witnessed being unearthed in Rome in 1506. The study for the Libyan Sibyl is an exquisite preparatory drawing from this time, revealing his use of a male model for a female figure.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto), c. 1510–11, red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, 28.9 × 21.4 cm ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art )

Michelangelo began painting the ceiling with the traditional method of using cartoons to transfer the design onto the wet plaster, but he became so proficient towards the end, he worked freehand. He also claimed to work without assistants (despite evidence otherwise), and preferred to keep his work private until finished. One story relays that he threw planks at Pope Julius II from the scaffolding, mistaking him for a spy![2]

Michelangelo, AB XIII, 111 Sonnet and self-portrait, 1509/1512 (Casa Buonarotti, Florence)

The ceiling took Michelangelo over four years to paint. Initially, he did not want the commission, claiming that painting was not his art. He wrote a satirical poem about his personal struggle paired with a caricature of himself standing to paint: “With my beard towards heaven… I am bent like a Syrian bow….”[3]

Michelangelo, Creation of Adam , ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (detail), 1508–12, Vatican, Rome

Mid-Career but not middle of the pack

Michelangelo was initially called to Rome in 1505 to carve the tomb of Julius II intended for the center of New St. Peter’s Basilica , soon to be under construction. If fully realized, the monument would have contained over forty life-size figures, impossible for Michelangelo to ever have finished. The memorial was finally erected, in a reduced form in 1545, as a wall tomb in S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Moses , 1513–15, Carrara marble, 254 cm (8 feet, 3 inches) high, Tomb of Pope Julius II (della Rovere), 1505–45, San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome (photo: Jörg Bittner Unna , CC BY 3.0)

The monumental Moses , intended for an upper corner, is now featured as the main figure. Two series of figures were never placed in the final arrangement: two bound “ slaves ” in the Louvre Museum in Paris and four struggling “captives” in the Accademia Museum in Florence. The Captives , likely carved in the 1520s, are bulky, block-like, and rough, where one can see the artist’s cross-hatching marks made with the gradina , a multi–toothed chisel . His preferred tool, the cane , a dog-toothed chisel, left distinct groove lines on the surface of the marble. Because of the roughness, these, and other sculptures, have been labeled non-finito , or unfinished, a topic much debated in scholarship.

From left to right: Michelangelo, Slaves (commonly referred to as the Dying Slave and the Rebellious Slave ), 1513–15, marble, 2.09 m high (Musée du Louvre, Paris, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Captives (commonly referred to as the Atlas Captive and the Bearded Captive ), c. 1530–34, marble, 2.77 m and 2.63 m high (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Michelangelo traveled back and forth from Rome and Florence during the late 1510s and 20s. In Florence, he worked for Julius’ successor, Pope Leo X de’ Medici, on the façade of the family’s church, San Lorenzo, which was never completed. It was here, though, where he honed his entrepreneurial skills, managing hundreds of workers under his direction. Michelangelo continued Medici employment under Pope Clement VII, designing the Laurentian Library and the New Sacristy .

Michelangelo, Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, 1526-33, marble, 630 x 420 cm (New Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 1527, during a period of political turmoil, the Florentine Republic took back control from the Medici. Two years later, the city came under siege by troops of Holy Roman Empire and the Medici were reinstalled. Despite his longtime connections to the family, Michelangelo, a republican at heart, left Florence forever in 1534.

Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–1541 (Vatican City, Rome) (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

Late life in the Eternal City

Michelangelo’s second fresco in the Sistine Chapel in Rome, the Last Judgment , was commissioned by Pope Paul III and was painted between 1535 and 1541. It also functioned as a study tool for artists. Giorgio Vasari, the sixteenth-century artist and biographer, claimed that artists no longer needed to study live models from nature since every conceivable human position was represented in Michelangelo’s fresco. To accomplish this, Michelangelo positioned tiny wax models to help develop the complex, large-scale composition. Reliance on Michelangelo’s contorted figures by later artists resulted in a sense of artificiality, a prized characteristic of Mannerism . The artist was constantly developing new working practices. For example, in order to extend working hours, Michelangelo made a headlamp with a special wax candle so he could paint into the late hours of the night, often forgetting to eat. Long days proved dangerous though, and he took a bad fall off the scaffolding, nearly breaking his leg.

Left: Michelangelo, Piazza and palazzi of the Capitoline Hill, Rome, 1536–1546 (photo: Lawrence OP , CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); Right: Michelangelo, Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, Rome, 1546–1564 (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Michelangelo became a Roman citizen in 1537, and it was here that he established his legacy as an architect. During the last two decades of his long life, Michelangelo focused on architectural commissions, sculpting only for himself. His major projects included renovating the Capitoline Hill and overseeing the construction of St. Peter’s (without pay for not only the salvation of his soul but also to retain complete creative control). As a devout Christian, Michelangelo made pilgrimage to all of Rome’s seven martyr churches during his old age. As he aged, he became more and more stubborn, riding his horse in the rain, for example. Owning horses was seen as an aristocratic endeavor, a status the artist became increasingly concerned with over the years. In his 1553 biography by Ascanio Condivi written with the artist’s consultation, Michelangelo emphasized his family’s nobility as a descendent of the counts of Canossa.

Michelangelo, Pietà for Vittoria Colonna, c. 1538–44, black chalk on paper, 28.9 x 18.9 cm ( Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum , Boston)

The artist never had children (he claimed his artworks were his children), or even proper students. Instead, he sought to groom his nephew Lionardo as the sole Buonarotti heir. Michelangelo also established many great friendships such as that with Vittoria Colonna, whom he gifted a devotional Pietà drawing. He turned to this theme for his own tomb memorial, now known as the Florentine Pietà . Michelangelo attempted to carve four figures out of one marble block, a nearly impossible task. This act was in direct competition with the famed ancient Laocoön , which, despite legend, was discovered by the artist to have been made of several pieces of stone. Here, Mary holds the dead Christ with Mary Magdalene on the left and Nicodemus behind them, figures who each witnessed the death of Christ. Michelangelo carved his self-portrait in the face of Nicodemus, placing himself over Christ in a last wish for salvation. In the end, this image did not adorn his tomb. However, he continued to carve almost daily up until his death in 1564; an onlooker described the eighty-something year old’s blows with a hammer as incredible.

Michelangelo, Deposition (The Florentine Pietà ), c. 1547–55, marble, 2.26 m high (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen , CC-BY 2.5)

The Florentine Art Academy, founded under the leadership of Vasari a year before Michelangelo died, erected the largest funerary memorial for an artist to date, naming him the father of the arts. Artists throughout the ages—from Caravaggio to Bernini, to Reynolds to Rodin , to Picasso to Hockney—looked to the art of Michelangelo as the founder of a forceful, new figural style. Michelangelo elevated the status of the artist more than any other artist of his time. He valued artistic freedom and personal expression, making art his way. Only with this in mind, can his creative vision and legend truly be appreciated.

Michelangelo’s tomb, Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence (photo: Walwyn , CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects , vol. IX, translated by Gaston du C. de Vere (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1912, p. 4–5).

- Ibid, p. 25.

- James Saslow, trans. The Poetry of Michelangelo (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), p. 70.

Additional resources:

Vasari’s Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects in English translation at Project Gutenberg

Second edition of Vasari’s Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects in Italian at Archive.org

Virtual tour of the Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo’s design for the Tomb of Pope Julius II della Rovere at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

See more pictures of the Medici Chapel (New Sacristy)

James Ackerman, The Architecture of Michelangelo (Chicago: University Chicago Press, 1986)

Francis Ames-Lewis and Paul Joannides, eds. Reactions to the Master: Michelangelo’s Effect on Art and Artists in the Sixteenth Century (Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2003)

Umberto Baldini and Perugi Liberto, The Complete Sculpture of Michelangelo (London. Thames and Hudson, 1982)

Carmen C Bambach, et. al, eds., Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman & Designer (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017)

Leonard Barkan, Michelangelo: A Life on Paper (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011)

Bernadine Barnes, Michelangelo and the Viewer in his Time (London: Reaction Books, 2017)

Paul Barolsky, Michelangelo’s Nose: A Myth and its Maker (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997)

______ , The Faun in the Garden: Michelangelo and the Poetic Origins of Italian Renaissance Art (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994)

Anscanio Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo . Edited by Hellmut Wohl. Translated by Alice Sedgwick Wohl. 2nd ed. (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999)

Robert J. Clements, Michelangelo: A Self-Portrait (New York: New York University Press, 1968)

Charles De Tolnay, Michelangelo: Sculptor, Painter, Architect (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975)

Rona Goffen. Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004)

Marcia B. Hall, ed. Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Howard Hibbard, Michelangelo . 2nd ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1974)

Deborah Parker, Michelangelo and the Art of Letter Writing (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Lisa Pon, “Michelangelo’s Lives : Sixteenth-Century Books by Vasari, Condivi, and Others.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 27 (1997): 1015–1037.

Pina Ragionieri and Gary M. Radke, Michelangelo: The Man and the Myth , exhibition catalogue. Translated by Christian and Silvia DuPont (Syracuse, NY: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008)

James M. Saslow, The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991)

Tamara Smithers, ed., Michelangelo in the New Millennium (Boston: Brill, 2016)

______ , The Cults of Raphael and Michelangelo: Artistic Sainthood and Memorials as a Second Life (New York and London: Routledge, 2023)

David Summers, Michelangelo and the Language of Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981)

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects . 10 vols. Translated by Gaston du C. De Vere ( New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1912)

______ , Lives of the Artists . 2. vols. Translated by George Bull (London: Penguin, 1965)

William E. Wallace, Michelangelo, God’s Architect: The Story of his Final Years and Greatest Masterpiece . Princeton: Princeton University, 2019.

______ , Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man and His Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010)

______ , Michelangelo: The Complete Sculpture, Painting, Architecture (New York: Universe, 2009)

______ , ed. Michelangelo, Selected Scholarship in English : Life and Early Works . 5 vols. (New York: Garland Publishing, 1995)

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Michelangelo

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) was an Italian artist, architect and poet, who is considered one of the greatest and most influential of all Renaissance figures. His most celebrated works, from a breathtaking portfolio of masterpieces, include the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome and the giant marble statue of David, which resides in the Galleria dell'Accademia of Florence.

Esteemed by his contemporaries as the greatest of living artists, Michelangelo was hugely influential on the artistic styles of High Renaissance, Mannerism, and Baroque. Still today, the great man's works continue to wrench from art lovers worldwide the feelings he expressly intended to produce in all of his art no matter the medium: admiration of form and motion, surprise and awe.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti was born in 1475 CE in Caprese, a small town near Florence, Italy . Unlike many other famous artists, Michelangelo was born into a prosperous family. When he reached 13 years of age, he was sent off to study in Florence under the celebrated fresco painter Domenico Ghirlandaio (c. 1449-1494 CE). The young artist spent two years as Ghirlandaio's apprentice but also visited many churches in the city , studying their artworks and making sketches. Michelangelo's big break came when his work was noticed by Lorenzo de Medici (1449-1492 CE), head of the great Florentine family of that name and a generous patron of the arts. It was in Lorenzo's impressive sculpture garden that the young artist was able to study firsthand the works of the great sculptors of antiquity, especially Roman sarcophagi decorated in high relief, and learn from the garden's artistic curator and noted sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni (c. 1420-1491 CE). Michelangelo would later create Lorenzo de Medici's marble tomb in the Medici family church of San Lorenzo in Florence.

The influence these Classical works had on Michelangelo is evident in the writhing figures in one of his first great masterpieces, the relief sculpture known as The Battle of Centaurs and Lapiths which is now on display in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence. The artist's preoccupation with antiquity in the first half of his career is amply evidenced in his work but also in his numerous deliberate attempts to pass off sculptures as actually ancient. In 1496 CE, for example, he sculpted the Sleeping Cupid (now lost) which he purposely aged to make it appear an authentic ancient work and which he successfully sold to Cardinal Raffaele Riario.

Michelangelo was, then, already focussing on the technique known as disegno where an artist concentrated above all in trying to capture the form, musculature, and poses of the human body through sketches on paper of Classical works which were then transformed into an entirely new sculpture or painting. Michelangelo also added to this artistic heritage a passion for rendering his figures with dramatic poses and doing so on a monumental scale, which perhaps explains his own preference for sculpture over other media . The combination of realist execution, grandeur, and dynamism would become the hallmark of the master's works in all media as he strove to create a world more beautiful than actually existed in reality.

The Leading Renaissance Artist

In 1496 CE Michelangelo moved on to Rome which gave him yet more opportunities to study examples of Classical art and architecture . It was in this period he created another masterpiece, the Pietà (see below). Returning to Florence c. 1500 CE, the artist was now well established and he was commissioned to create a figure for no less a place than the Cathedral of Florence. Michelangelo was given a massive block of highly-prized Carrara marble that nobody quite knew what to do with. The result was another masterpiece, probably the artist's most famous sculpture of all: David (see below). Next up was a chef-d'oeuvre using paints, demonstrating Michelangelo was by no means limited to sculpture. The Holy Family was painted in 1503 CE and the work is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Next came an intriguing meeting of great minds when Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) both worked on frescoes in the Council Hall of Florence. The subject of Michelangelo's work was the Battle of Cascina but, like Leonardo's effort here, it was left unfinished. It can only be speculated what each great artist might have learned from the other at this time.

Michelangelo returned to Rome to work on the tomb of Pope Julius II (r. 1503-1513 CE), and then he was given perhaps his most challenging commission - to paint the ceiling of the Vatican City's Sistine Chapel (see below). Despite working largely alone and very often in an uncomfortable position on top of a scaffold, the ceiling was completed remarkably quickly. Finished by 1512 CE, the work may not have pleased everyone in the Church, but its central vision of God amongst the clouds reaching out to touch the finger of Adam has become one of the most reproduced images of all time.

Michelangelo would continue to sculpt and, much more rarely, paint for the rest of his life. He continued to write his much-admired sonnets which were frequently dedicated to the poetess Vittoria Colonna (1490-1547 CE), although many were scribbled on the backs of sketches and bills. In this example, Sonnet 151 (c. 1538-1544 CE), the artist compares art's failure to prevent death with the search for true love:

Not even the best of artists has any conception that a single marble block does not contain within its excess, and that is only attained by the hand that obeys the intellect. The pain I flee from and the joy I hope for are similarly hidden in you, lovely lady, lofty and divine; but, to my mortal harm, my art gives results the reverse of what I wish. Love, therefore, cannot be blamed for my pain, nor can your beauty, your hardness, or your scorn, nor fortune, nor my destiny, nor chance, if you hold both death and mercy in your heart at the same time, and my lowly wits, though burning, cannot draw from it anything but death. (Paoletti, 404)

There were, too, many important architectural projects, such as the Laurentian Library, San Lorenzo, Florence (1525 CE) with its 46-metre (150 ft.) long reading room, a triumphal combination of aesthetics and function. Other projects included the new-look Capitoline Hill in Rome (begun in 1544 CE), the soaring dome of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome (from 1547 CE but not completed until 1590 CE) for which Michelangelo refused to accept a salary, and the Medici sepulchral chapel in Florence. Fittingly, throughout the 16th century CE, the Medici chapel became a place frequently visited by aspiring artists who came to admire and learn from this master of the arts' unique and visionary combination of architecture and sculpture. Michelangelo died on 18 February 1564 CE in Rome and was buried with much ceremony in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence.

Reputation & Legacy

The great artist was himself captured in several surviving works of art. One striking example is the bronze bust by his compatriot Daniele da Volterra (1509-1566 CE), which, created c. 1564 CE, now resides in the Bargello of Florence. The sculpture is realistic and shows the bearded Michelangelo with wrinkles aplenty and with the slightly flattened nose he had carried ever since the artist Pietro Torrigiano (1472-1528 CE) had broken it when the pair were youths (Torrigiano was exiled from Florence as a consequence).

A more detailed record of Michelangelo survives in two biographies written during the artist's lifetime by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574 CE) and Ascanio Condivi (1525-1574 CE). The Tuscan artist Vasari completed his The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors in 1550 CE but then extensively revised and expanded the work in 1568 CE. The history is a monumental record of Renaissance artists, their works and the anecdotal stories associated with them, and so Vasari is considered one of the pioneers of art history. Fellow Italian artist Condivi, meanwhile, was a pupil of Michelangelo's in Rome, and he wrote his Life of Michelangelo in 1553 CE, a work which was supervised by the great master himself (which perhaps explains a number of fictitious or exaggerated elements).

These two biographies helped establish Michelangelo's reputation as a living legend as fellow artists recognised his genius and contribution to the revival of art during the Renaissance. Naturally, Michelangelo's great works spoke for themselves, and those who could not see them in person could admire or study them in the many engravings made which were distributed across Europe . His fame also went beyond Europe. The Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512 CE) heard of the artist's skills and invited him, without success, to his court. Michelangelo's works were even being collected, especially in France. In short, Michelangelo was considered nothing less than divine - a term frequently used for the artist during his lifetime - and a possessor of awesome artistic power, what his contemporaries termed terribilità . The light the great man cast on Western art and architecture continued to shine long after his death and his work was especially influential on the development of Mannerism and the subsequent Baroque style.

Masterpieces

The Pietà is a depiction in marble of the Virgin Mary who mourns over the body of Jesus Christ which rests across her lap. Completed between 1497 and 1500 CE, the work was commissioned by a French cardinal for his tomb in a chapel in Rome. Standing 1.74 metres (5 ft. 8 inches) tall, it now resides in St. Peter's Basilica. The work combines all aspects of the sculptor's art: a hyper-realistic depiction of the human body, complex folds of drapery, the serene and contemplative face of Mary, the languid corpse of Jesus , and a composition that reminds of northern devotional statues but offers something never before seen in Italian art. That Michelangelo was highly satisfied with the result is evidenced in the anecdote that he subsequently added his signature after a rival artist had claimed to have been its creator.

As mentioned above, Michelangelo's offering to the Cathedral of Florence was a marble sculpture of the Biblical king David who, in his youth, famously killed the troublesome giant Goliath. The figure is much larger than life-size - around 5.20 metres (17 feet) tall - and so big that it could not be placed on the roof of the cathedral as intended but was stood instead in the facing square. Michelangelo received around 400 florins for a work he had started in 1501 CE and completed in 1504 CE. David now stands in the Accademia Gallery of Florence while a full-size replica stands in the open air of the Palazzo della Signoria.

The figure is all white now but originally had three gilded elements: the tree stump support, a waist belt of leaves and a garland on his head. The only identification that this is a figure of David is the sling over the figure's left shoulder. Further, the maturity of the body for what really should be a youth, together with the nudity of the figure, strongly remind of the colossal statues of antiquity, especially of Hercules . It cannot be coincidental that Hercules also appeared on the official seal of the city of Florence. Here, then, was a message in art that the city believed itself the equal, perhaps even the better of any city in antiquity. Michelangelo has clearly gone beyond the restraints of Classical sculpture and created a figure which is palpably tense, an effect only accentuated by David's furrowed brow and determined stare.

The Sistine Chapel

As noted, Michelangelo was commissioned to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, a building only just completed in 1480 CE. The ceiling had cracked badly in 1504 CE and was repaired. This, then, was an opportunity to add to the chapel's already impressive interior decoration. Michelangelo was far from keen on the project which would occupy him from 1508 to 1512 CE - and there were frequent heated quarrels with the Pope - but it is today considered one of his signature works. The frescos are painted in very bright colours and, to aid the viewer who must stand some metres below, Michelangelo used the technique of contrasting colours next to each other.

The entire ceiling covers an area measuring 39 x 13.7 metres (128 x 45 ft.). The separate panels show a cycle of episodes from the Bible narrating the Creation to the time of Noah . Interestingly, the creation of Eve is the central panel, not the creation of Adam, although this may simply be because the scenes are chronological starting from the altar wall . There are also seven prophets, five sibyls, and four ignudi which have nothing whatsoever to do with the religious narrative but which show Michelangelo's love of boldly rendered figures in dramatic poses.

The work was an immediate success with almost everyone who saw it but there were some rumblings of discontent. The main objection was the amount of nudity and the depiction of genitalia in a handful of figures. In addition, The Last Judgement section of the chapel, which was added to the altar much later by Michelangelo between 1536 and 1541 CE, was also not well-received by some members of the clergy. The fact that Jesus did not have his conventional beard and looked a bit younger than usual were particular points of contention. The artist's grasp of essential theology, or perhaps his lack of concern with it for he was noted for his piety, and the appearance of yet more genitalia led to some clergy going so far as to declare the work a heresy. There were even calls to destroy it. Fortunately for posterity, the more moderate strategy was adopted of covering the offending nude elements. The task of retouching the frescoes was given to Daniele da Volterra, and this artist consequently gained the rather unfortunate nickname of Il Braghettone or 'the breeches-maker'.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

As mentioned, Michelangelo was commissioned by Julius II in 1505 CE to design an imposing tomb for the leader of the Roman Church. Starting out on paper as a grandiose monument, the tomb was finally completed in 1547 CE after many of the planned extravagances were abandoned. One survivor is the seated statue of Moses sculpted by Michelangelo which has the biblical figure holding his staff and pulling on an impressively long beard, apparently to demonstrate his awe of God. The statue was meant to be seen from below and hence Michelangelo incorporated several optical corrections. The figure, measuring 2.35 metres (7 ft. 9 inches) in height, was completed around 1520 CE and resides in the San Pietro in Vincoli church in Rome.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Anderson, Christy. Renaissance Architecture. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Campbell, Gordon. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Giorgio Vasari - Lives (Michelangelo) , accessed 18 Aug 2020.

- Hale, J.R. The Thames & Hudson Dictionary of the Italian Renaissance by J. R. Hale. Thames & Hudson, 2020.

- Murray, Peter. The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance. Schocken, 1997.

- Paoletti, John T. & Radke, Gary M. Art in Renaissance Italy. Pearson, 2011.

- Rundle, David. The Hutchinson Encyclopedia of the Renaissance. Helicon, 1999.

- Welch, Evelyn. Art in Renaissance Italy. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Woods, Kim W. Making Renaissance Art. Yale University Press, 2007.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Related Content

Pietro Perugino

Andrea Mantegna

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Benvenuto Cellini

Piero della Francesca

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Cartwright, M. (2020, August 18). Michelangelo . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Michelangelo/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Michelangelo ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified August 18, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/Michelangelo/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Michelangelo ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 18 Aug 2020. Web. 06 Sep 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 18 August 2020. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Biography Online

Michelangelo Biography

Short biography of Michelangelo

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born on 6 March 1475, in a Florentine village called Caprese. His father was a serving magistrate of the Florentine Republic and came from an important family.

However, Michelangelo did not wish to imitate his father’s career and was attracted to the artistic world. At the time, being an artist was considered an inferior occupation for a family of his standing. But, aged 13, Michelangelo was apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, the leading fresco wall painter in Florence. Here Michelangelo learned some of the basic painting techniques and also taught himself new skills such as sculpting. He loved sculpting more than painting, feeling that sculptor allowed the creation of living works of art.

Madonna of the stairs – Michelangelo’s earliest works

His talents were soon noticed by one of the most powerful families in Florence – Lorenzo de’ Medici. Here, at de’ Medici’s court, Michelangelo was able to learn from the classic Masters. He also gained an all-round education, even taking part in dissections to learn more about the anatomy of the human body and muscles. He was also very ambitious becoming determined to improve upon the great classics of Greek and Latin art and become famous throughout the artistic world.

His Pietà can still be seen inside the Basilica of St Peter in Rome, Italy.

Michelangelo’s Pietà

His next most famous sculpture was his huge undertaking of a life-size David . This was hewn from a huge block of marble dragged down from a nearby Florentine mine. Michelangelo created a masterpiece, a perfection of the human form, and many agreed that Michelangelo had surpassed his classic predecessors. David was put pride of place in front of the seat of Florentine government. A remarkable feature of David and other Michelangelo’s sculptures was the smoothness of the finished product, he left no sign of any chisel mark – everything was beautifully smooth. He once claimed that the sculptures were already living in the marble and all he had to do was carve them out.

Michelangelo’s David

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free. “

– Michelangelo

Michelangelo was a contemporary of the other sublime artist of his generation, the genius Leonardo da Vinci . However, with Michelangelo’s short temper and pride, the two had a difficult relationship. At one time, the Florentine government wanted the two geniuses of art to work side by side, each painting a side of a council chamber. But, it was not a success and neither finished.

In 1505, Pope Julius II summoned Michelangelo to Rome and commissioned him in a number of projects. The first was to create a magnificent tomb. However, this ran into problems as the Pope later diverted funds to the ambitious scheme to rebuild St Peter’s. Michelangelo was quick to anger – it did not matter even if it was the Pope. But the Pope deflected Michelangelo’s anger and, through a combination of persuasion, threat and flattery later offered Michelangelo a new commission to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapel

This was a huge undertaking which Michelangelo began in 1508. Initially, the Pope suggested scenes from the New Testament, but Michelangelo chose the Old Testament with its great variety of characters and dramatic scenes. The project took four years to complete and involved Michelangelo working in awkward positions with paint frequently dripping onto his face. After months of working at awkward angles, he developed serious neck pain, but he continued to work at a furious pace trying to do the great fresco painting singlehandedly. Despite the magnitude of the task, Michelangelo did not want to delegate any work to assistants. He wanted to succeed alone; he felt like it was his divine mission.

The Sistine Chapel which took Michelangelo four years to paint.

“If you knew how much work went into it, you would not call it genius.”

– Michelangelo as quoted in Speeches & Presentations Unzipped (2007) by Lori Rozakis, p. 71