Stereotype Threat: Definition and Examples

Erin Heaning

Clinical Safety Strategist at Bristol Myers Squibb

Psychology Graduate, Princeton University

Erin Heaning, a holder of a BA (Hons) in Psychology from Princeton University, has experienced as a research assistant at the Princeton Baby Lab.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Stereotype threat is when individuals fear they may confirm negative stereotypes about their social group. This fear can negatively affect their performance and reinforce the stereotype, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy . It can impact various domains, notably academic and professional performance.

- Stereotype threat is the psychological phenomenon where an individual feels at risk of confirming a negative stereotype about a group they identify with.

- Stereotype threat contributes to achievement and opportunity gaps among racial, ethnic, gender, and cultural groups, — particularly in academics and the workplace.

- Interventions such as teaching about stereotype threat and growth mindset, implementing self-affirmation assignments, and highlighting positive role models have been proven to impact fighting stereotype threat positively.

The term stereotype threat was first defined by researchers Steele and Aronson as “being at risk of confirming, as self-characteristic, a negative stereotype about one’s group” (Steele et al., 1995).

In other words, stereotype threat refers to an individual’s fear that their actions or behaviors will support negative ideas about a group to which they belong.

For instance, if an individual is worried that performing badly on a test will confirm people’s negative beliefs about the intelligence of their race, gender, culture, ethnicity, or other forms of identity, they are experiencing stereotype threat.

The effects of stereotype threat are especially evident in the classroom, but they can also follow an individual into the workplace and throughout the rest of their lives.

Steele and Aronson’s original study of this effect looked at black and white students’ performance on an academic test, specifically, a 30-minute test made up of items from the verbal section of the Graduate Record Examination (GRE).

Steele and Aronson chose this procedure in response to the racial stereotype that black students are less intelligent or less capable than white students.

Given this stereotype threat against black students’ academic abilities, the researchers hypothesized that when black students were primed with the belief that the test was diagnostic of intellectual ability, they would perform worse than white students.

Confirming their suspicions, Steele and Aronson’s findings showed that black participants underperformed white participants when the test was labeled diagnostic of intellectual ability, but they performed equally well when the test was labeled non-diagnostic (Steele et al., 1995).

By labeling the test as diagnostic of intelligence in the stereotype threat condition, the experiment effectively made black students more vulnerable to judgment about their race’s academic ability.

And so, with their mental energy being used up by doubt and fear of failure, their academic performance ironically worsens.

Stereotype Threat Examples

The original investigation of stereotype threat by Steele and Aronson in 1995 investigated the relationship between race and academic performance.

Since then, additional studies have evidenced the role of stereotype threat in negatively impacting the academic performance of black students (Osborne et al., 2001).

However, in addition to race, recall stereotype threat can result from negative stereotypes against any aspect of one’s identity, such as ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual orientation, and more.

For instance, Spencer and colleagues showed stereotype threat might also underlie gender differences in advanced math performance (Spencer et al., 1999).

Based on the cultural belief that women have weaker math abilities, the researchers in this study hypothesized that reducing stereotype threats may help to eliminate gender differences in math performance.

In support of their hypothesis, their findings showed that when a math test was described as producing gender differences, women performed worse, but when the test was described as not producing gender differences, women performed equally as well.

Apart from race and gender, stereotype threat has also been extended to studies on the academic underperformance of students from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds.

In a study by Croizet and colleagues, the researchers showed that when a test was described as measuring intellectual ability, lower SES participants performed worse than higher SES participants, but this difference was eliminated when the test was labeled non-diagnostic (Croizet et al., 2021).

These findings strongly contest the cultural belief that members of lower SES backgrounds have the lesser intellectual ability . Instead, studies such as these show that societal stereotypes might, in fact, be holding people back from the academic achievement they might otherwise attain.

Be it race, gender, SES, or some other form of identity, examples of stereotype threat impacting the achievement of stigmatized groups are evident.

Theories of Stereotype Threat

As these examples show, stereotype threat is a very prevalent issue that exaggerates racial and gender disparities in performance, but what is it that causes this stereotype threat effect?

In recent adaptations of stereotype threat studies, researchers have connected stereotype threat to the idea of “belonging uncertainty,” which undermines an individual’s sense of social acceptance and identity (Walton et al., 2007).

The desire for social belonging is a basic human motivation, and members of stigmatized groups may be more uncertain of their social bonds than others.

Therefore, to establish a sense of belonging, individuals may do all they can to avoid the threat of embarrassment or failure that could come from confirming negative stereotypes about their identity.

Consistent with this idea, Inzlicht’s “stigma as ego depletion ” theory further hypothesizes that stigma drains an individual’s self-regulatory resources, impairing their performance on following tasks (Inzlicht et al., 2006).

In this research, Inzlicht discusses how members of a stigmatized group may have fewer resources to regulate their actions or behaviors when they feel they are in a threatening or discriminatory environment.

In other words, one’s cognitive abilities can be thought of as a fuel tank that starts on full, but as people face discrimination or negative stereotypes, that fuel is used up by focusing on doubt or concern over their own abilities.

As a result, stigmatized individuals spend so much mental energy worrying about their own talents, skills, or capabilities that they do not have the mental energy left to reach their full potential in following tasks.

Stereotype Threat and the Achievement Gap

Stereotype threat is especially dangerous due to the far-reaching impacts it has not only on the individual but on society as a whole.

For instance, at the individual level, stereotype threat can increase anxiety and stress as people actively attempt to disprove negative stereotypes about themselves.

Faced with negative stereotypes and fear that they will confirm them, people might become more disengaged from certain subject fields or areas of interest.

By establishing this fear that one might confirm negative stereotypes about one’s group (such as lesser intellectual ability), stereotype threat may also lead to a lack of confidence, doubt, self-defeating behavior, and a disengaged attitude.

Ironically, these resulting negative behaviors could cause a self-fulfilling prophecy for the individual who ends up living up to that negative stereotype.

People might even change their career trajectory or aspirations to avoid the threat of failure that society assigns to their identity.

For instance, a woman who is interested in math might still choose to avoid a major or career in STEM for fear she will prove lesser than her male counterparts, resulting in a lower number of women in STEM fields.

At a societal level, the combined impacts of these stereotype threats lead to a culture in which people of certain groups or identities are handicapped.

Stereotype threat can reduce academic focus and performance by creating a high cognitive load of vulnerabilities and doubt — contributing to the long-standing racial and gender gap in achievement.

For instance, standardized testing in school represents one such place where the effects of stereotype threat are especially striking.

Currently, exams such as the SAT, ACT, and GRE are crucial components of applications for higher education. And although there have been many arguments as to the unreliability of these exams and their inherent unfairness, most higher-education schools still require them in their admissions process.

Supporters of standardized tests argue these exams are meant to reflect academic ability and reasoning skills, but opponents say they probably measure access to opportunity more than academic ability.

The apparent racial and SES gaps in SAT scores are evidence of standard test opponents’ claims, as white and affluent individuals continue to outperform black, Latinx, and lower-income students.

Given society’s value of standardized tests as a diagnostic of intellectual ability, it’s no wonder that stereotype threat might be at play in exaggerating these scoring gaps.

Furthermore, since test scores impact stigmatized groups’ opportunities and social mobility, inequalities in the SAT score distribution reflect and reinforce racial inequalities across generations (Reeves & Halikias, 2017).

As a result, the effects of stereotype threat today continue to contribute to the future of this long-standing achievement gap.

Beyond school, the effects of stereotype threat can also follow people into the workplace. Earlier, this paper discussed how entire career trajectories might be changed given the self-doubt caused by stereotype threat.

Stereotype threat can prevent people from applying for jobs, asking for promotions, or performing confidently within an organization. Additionally, workers who face negative stereotypes surrounding their performance or intellectual ability may exhibit greater anxiety, reduced effort, and less creativity on the job.

In addition to decreasing workplace performance or productivity, stereotype threat also reduces the representation of stigmatized groups in corporations.

For instance, as stereotype threats follow people from academics into the workplace, there can be downstream impacts such as an inequality in the number of women in leadership positions and lower representation of ethnic minorities in CEO positions.

Therefore, the achievement gap exists not only in academics. Instead, it follows individuals into their careers and the rest of their lives.

How to Fight Stereotype Threat

Given the far-reaching impacts of stereotype threat, there has been much research on how to reduce its effects and help stigmatized populations succeed without fear of discrimination.

Some interventions have shown that simply teaching people about stereotype threat reduces its effect.

In one study on women’s math performance, no significant difference in scores was found between men and women in the condition in which stereotype threat was explained (Johns et al., 2005).

This could be due to the idea that teaching people about stereotype threat allows individuals to attribute anxiety and stress to external stereotypes rather than their internalized doubt.

Additionally, educating students on a growth mindset (or the idea that intelligence is a learned and not a fixed trait) can reduce stereotype threat.

In one study on this intervention, black students who were encouraged to view intelligence as a malleable trait reported greater enjoyment and engagement in academics and obtained higher grade point averages than control groups (Aronson et al., 2002).

By teaching intelligence as a trait that can be changed through one’s own effort and attention, a growth mindset makes students’ performances less vulnerable to stereotype threat, helping them maintain engagement with academics without doubting their abilities.

Drawing on this growth-mindset theory, self-affirmation interventions have also been proven to help fight the effects of stereotype threat. Self-affirmation refers to recognizing and asserting the value of oneself and their abilities.

In one study of this technique by Cohen and colleagues, black students were assigned a brief, in-class writing assignment reaffirming their personal adequacy.

As a result of this assignment, students’ grades significantly improved, reducing the racial achievement gap by forty percent (Cohen et al. 2006). By helping students acknowledge their own abilities and talents, self-affirmation assignments such as these can work wonders in building students’ confidence and overcoming internalized stereotypes.

Finally, role models can play a valuable role in reducing stereotype threat.

One study on role models showed that when college women first read about women who had succeeded in architecture, law, medicine, and invention, they performed significantly better on a difficult mathematics test (McIntyre et al., 2003).

The importance of this study is that it shows that representation doesn’t have to mean physical exposure to counter-stereotypical role models. Instead, increasing representation and fighting negative stereotypes in television, movies, or literature can also change public perception of stigmatized groups.

Furthermore, exposure to these counter-stereotypical role models at an early age can influence aspirations, career choices, and confidence in children, which can be carried through adulthood.

By implementing these measures, academic institutions and workplaces can make an effort to fight the threat of stereotypes and build a fairer and less discriminatory society moving forward.

Learning Check

Which of the following is the best example of stereotype threat?

- A female student feels nervous about a math test due to the stereotype that women are not as good at math as men.

- An elderly person deciding not to participate in physical activity out of fear of injury.

- A football player spends extra time practicing to improve his skills.

- Asian students pushing themselves to excel in math to align with the stereotype that Asians are good at math.

- A person choosing not to attend a social gathering because they are introverted and prefer smaller social settings.

Answer : The best example of stereotype threat is 1) A female student feeling nervous about a math test due to the stereotype that women are not as good at math as men. This situation involves fear of confirming a negative stereotype about her social group, which is characteristic of stereotype threat.

Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the Effects of Stereotype Threat on African American College Students by Shaping Theories of Intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38 , 113-125.

Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Apfel, N. & Master, A. (2006). Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science, 313 , 1307-1310.

Croizet, J. C., & Claire, T. (1998). Extending the concept of stereotype threat to social class: The intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24 (6), 588-594.

Inzlicht, M., McKay, L., & Aronson, J. (2006). Stigma as ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychological Science, 17 (3), 262-269.

Johns, M., Schmader, T., & Martens, A. (2005). Knowing is half the battle: Teaching stereotype threat as a means of improving women’s math performance. Psychological science, 16 (3), 175-179.

McIntyre, R. B., Paulson, R., & Lord, C. (2003). Alleviating women’s mathematics stereotype threat through salience of group achievements. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39 , 83-90.

Reeves, R. V., & Halikias, D. (2017, August 15). Race gaps in SAT scores highlight inequality and hinder upward mobility. Brookings. Retrieved January 11, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/race-gaps-in-sat-scores-highlight-inequality-and-hinder-upward-mobility/

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of experimental social psychology, 35 (1), 4-28.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and social psychology , 69 (5), 797.

Osborne, J. W. (2001). Testing stereotype threat: Does anxiety explain race and sex differences in achievement?. Contemporary educational psychology, 26 (3), 291-310.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and social psychology, 92 (1), 82.

Further Information

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69 (5), 797.

Aronson, J., Lustina, M. J., Good, C., Keough, K., Steele, C. M., & Brown, J. (1999). When white men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35 (1), 29-46.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Twenty Years of Stereotype Threat Research: A Review of Psychological Mediators

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Edge Hill University, Ormskirk, Lancashire, England, United Kingdom.

- PMID: 26752551

- PMCID: PMC4713435

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146487

This systematic literature review appraises critically the mediating variables of stereotype threat. A bibliographic search was conducted across electronic databases between 1995 and 2015. The search identified 45 experiments from 38 articles and 17 unique proposed mediators that were categorized into affective/subjective (n = 6), cognitive (n = 7) and motivational mechanisms (n = 4). Empirical support was accrued for mediators such as anxiety, negative thinking, and mind-wandering, which are suggested to co-opt working memory resources under stereotype threat. Other research points to the assertion that stereotype threatened individuals may be motivated to disconfirm negative stereotypes, which can have a paradoxical effect of hampering performance. However, stereotype threat appears to affect diverse social groups in different ways, with no one mediator providing unequivocal empirical support. Underpinned by the multi-threat framework, the discussion postulates that different forms of stereotype threat may be mediated by distinct mechanisms.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Fig 1. Process of article inclusion (following…

Fig 1. Process of article inclusion (following PRISMA).

Similar articles

- Distracted by the Unthought - Suppression and Reappraisal of Mind Wandering under Stereotype Threat. Schuster C, Martiny SE, Schmader T. Schuster C, et al. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 27;10(3):e0122207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122207. eCollection 2015. PLoS One. 2015. PMID: 25815814 Free PMC article.

- Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: examining the influence of emotion regulation. Johns M, Inzlicht M, Schmader T. Johns M, et al. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2008 Nov;137(4):691-705. doi: 10.1037/a0013834. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2008. PMID: 18999361 Free PMC article.

- An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. Schmader T, et al. Psychol Rev. 2008 Apr;115(2):336-56. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. Psychol Rev. 2008. PMID: 18426293 Free PMC article. Review.

- Stereotype threat can both enhance and impair older adults' memory. Barber SJ, Mather M. Barber SJ, et al. Psychol Sci. 2013 Dec;24(12):2522-9. doi: 10.1177/0956797613497023. Epub 2013 Oct 22. Psychol Sci. 2013. PMID: 24150969 Free PMC article.

- Toward a New Approach to Investigate the Role of Working Memory in Stereotype Threat Effects. Piroelle M, Abadie M, Régner I. Piroelle M, et al. Brain Sci. 2022 Dec 1;12(12):1647. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12121647. Brain Sci. 2022. PMID: 36552105 Free PMC article. Review.

- Protocol for a meta-analysis of stereotype threat in African Americans. Warne RT, Larsen RAA. Warne RT, et al. PLoS One. 2024 Jul 24;19(7):e0306030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0306030. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 39046955 Free PMC article.

- Influence of Role Expectancy on Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Patients With Migraine: A Randomized Clinical Trial. May A, Carvalho GF, Schwarz A, Basedau H. May A, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Apr 1;7(4):e243223. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3223. JAMA Netw Open. 2024. PMID: 38656579 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

- Stereotyping of student service members and Veterans on a university campus in the U.S. Motl TC, George KA, Gibson BJ, Mollenhauer MA, Birke L. Motl TC, et al. Mil Psychol. 2022 Mar 1;34(5):604-615. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2021.2025012. eCollection 2022. Mil Psychol. 2022. PMID: 38536289 Free PMC article.

- The Effect of Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Stereotype Threat on Inhibitory Control in Individuals with Different Household Incomes. Wang S, Yang D. Wang S, et al. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023 Dec 18;13(12):1016. doi: 10.3390/bs13121016. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023. PMID: 38131872 Free PMC article.

- Stereotype Threat and Gender Bias in Internal Medicine Residency: It is Still Hard to be in Charge. Frank AK, Lin JJ, Warren SB, Bullock JL, O'Sullivan P, Malishchak LE, Berman RA, Yialamas MA, Hauer KE. Frank AK, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2024 Mar;39(4):636-642. doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08498-5. Epub 2023 Nov 20. J Gen Intern Med. 2024. PMID: 37985610 Free PMC article.

- Derks B, Inzlicht M, Kang S. The neuroscience of stigma and stereotype threat. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2008;11: 163–181. 10.1177/136843020708803 - DOI

- Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol Rev. 2008;115: 336–356. 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336 - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69: 797–811. 10.1037/0022-3514/0022-3514.69.5.797 - DOI - PubMed

- Devine PG, Brodish AB. Modern classics in social psychology. Psychol Inq. 2003;14: 196–202. 10.1080/1047840X.2003.9682879 - DOI

- Fiske ST. The discomfort index: How to spot a really good idea whose time has come. Psychological Inquiry. 2003;14: 203–208. 10.1080/1047840X.2003.9682880 - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Grants and funding, linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

- Public Library of Science

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

REVIEW article

Addressing stereotype threat is critical to diversity and inclusion in organizational psychology.

- Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Missouri-St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Recently researchers have debated the relevance of stereotype threat to the workplace. Critics have argued that stereotype threat is not relevant in high stakes testing such as in personnel selection. We and others argue that stereotype threat is highly relevant in personnel selection, but our review focused on underexplored areas including effects of stereotype threat beyond test performance and the application of brief, low-cost interventions in the workplace. Relevant to the workplace, stereotype threat can reduce domain identification, job engagement, career aspirations, and receptivity to feedback. Stereotype threat has consequences in other relevant domains including leadership, entrepreneurship, negotiations, and competitiveness. Several institutional and individual level intervention strategies that have been field-tested and are easy to implement show promise for practitioners including: addressing environmental cues, valuing diversity, wise feedback, organizational mindsets, reattribution training, reframing the task, values-affirmation, utility-value, belonging, communal goal affordances, interdependent worldviews, and teaching about stereotype threat. This review integrates criticisms and evidence into one accessible source for practitioners and provides recommendations for implementing effective, low-cost interventions in the workplace.

“Is stereotype threat a useful construct for organizational psychology research and practice?” This is the title of a focal article in a recent volume of Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice ( Kalokerinos et al., 2014 ). The mere publication of such a paper suggests a debate in the field of industrial-organizational (I/O) psychology on the extent to which research on stereotype threat is applicable to the workplace. Stereotype threat is the fear or anxiety of confirming a negative stereotype about one’s social group (e.g., women are bad at math). Members of stereotyped groups (e.g., women, racial minorities) can experience stereotype threat in evaluative situations, which often leads to underperformance ( Steele and Aronson, 1995 ). The paper generated 16 commentaries from researchers and practitioners in I/O psychology and related fields, arguing both for and against the relevance of stereotype threat to I/O psychology.

Critics of stereotype threat research have four primary arguments: (1) mixed effects in operational high stakes testing environments ( Cullen et al., 2004 ; Stricker and Ward, 2004 ; Sackett and Ryan, 2012 ); (2) necessary boundary conditions ( Sackett, 2003 ; Sackett and Ryan, 2012 ; Ryan and Sackett, 2013 ); (3) lack of field studies ( Kray and Shirako, 2012 ; Kalokerinos et al., 2014 ; Kenny and Briner, 2014 ; Streets and Major, 2014 ); and (4) impracticality of implementing workplace interventions ( Streets and Major, 2014 ). Several publications have addressed the widely discussed arguments on high stakes testing ( Cullen et al., 2004 ; Aronson and Dee, 2012 ; Sackett and Ryan, 2012 ; Walton et al., 2015a ) and the boundary conditions of stereotype threat ( Sackett, 2003 ; Sackett and Ryan, 2012 ; Ryan and Sackett, 2013 ). Throughout our review we provide evidence to counter the third and fourth criticisms on the lack of field studies and impracticality of workplace interventions.

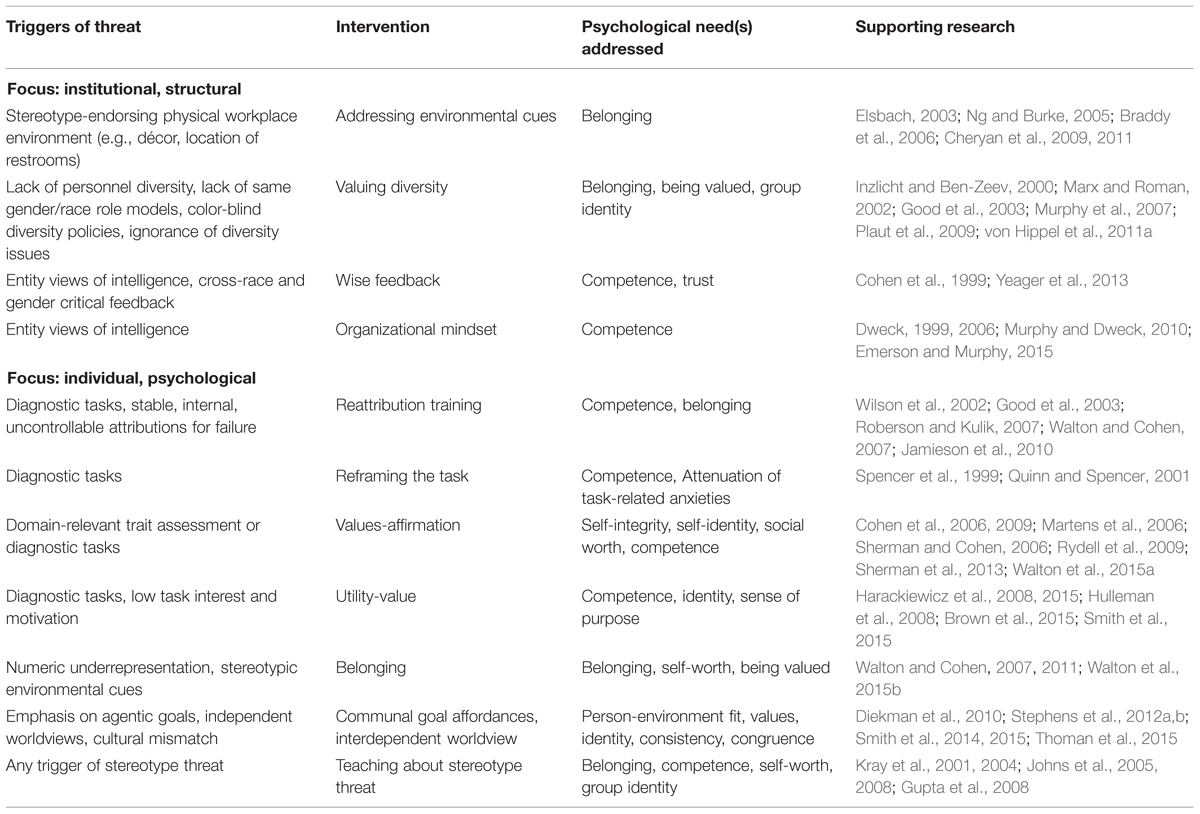

This review contributes to the growing attempt to apply research in the stereotype threat domain to the workplace ( Aronson and Dee, 2012 ; Kang and Inzlicht, 2014 ; Walton et al., 2015a ). We review the literature on the effects of stereotype threat beyond performance in an attempt to bring awareness to an area of stereotype threat research that may be underappreciated by practitioners due to its initial appearance as irrelevant ( Kang and Inzlicht, 2014 ; Spencer et al., 2015 ). Highly relevant to I/O researchers and practitioners, stereotype threat can affect domain identification, job engagement, career aspirations, and openness to feedback. Another area that needs greater dissemination is the effects of stereotype threat in domains other than selection and high stakes testing, such as leadership, entrepreneurship, negotiations, and competitiveness. The content and organization of our review on the antecedents and consequences of stereotype threat in the workplace is similar to previous work (see Kray and Shirako, 2012 ; Kalokerinos et al., 2014 ). We complete the review by describing several institutional and individual level interventions that are brief, easily implementable, have been field tested, and are low-cost (summarized in Table 1 ). We provide recommendations for practitioners to consider how to implement the interventions in the workplace.

TABLE 1. Summary of stereotype threat interventions adaptable to the workplace.

Effects of Stereotype Threat Beyond Performance

When research on stereotype threat was first published, the focus was on academic test performance for women and racial minorities ( Steele and Aronson, 1995 ). However, since this time research has expounded, cataloging numerous psychological, and behavioral outcomes that are affected by experiencing stereotype threat ( Schmader et al., 2008 ; Inzlicht et al., 2012 ). Research on stereotype threat spillover has documented pernicious effects of stereotype threat beyond performance ( Inzlicht and Kang, 2010 ; Inzlicht et al., 2011 ). Research on stereotype threat in an I/O context similarly has focused on performance as the key outcome (e.g., Sackett et al., 2001 ; Sackett and Ryan, 2012 ). It seems that because the effects of stereotype threat in high-stakes testing has been controversial ( Kalokerinos et al., 2014 ), the overemphasis on performance may have undermined I/O psychology’s research focused on other outcomes ( Kray and Shirako, 2012 ; Kang and Inzlicht, 2014 ). Indeed, research demonstrates that stereotype threat spillover effects are likely underestimated and may account for some of the null findings of stereotype threat on performance in field studies ( Inzlicht and Kang, 2010 ; Inzlicht et al., 2011 ; Kang and Inzlicht, 2014 ). In this section, we first describe the psychological processes responsible for stereotype threat spillover effects. We then review research showing that stereotype threat negatively impacts outcomes beyond performance (see Spencer et al., 2015 ). These negative outcomes are critical for I/O practitioners to consider when evaluating the usefulness of stereotype threat in the workplace. Although there are many outcomes affected by stereotype threat including intrapersonal, interpersonal, and employer–employee outcomes ( Kray and Shirako, 2012 ; Kalokerinos et al., 2014 ), we focus on four outcomes that are linked to other downstream effects relevant to the workplace: openness to feedback ( Roberson et al., 2003 ), domain identification ( Crocker et al., 1998 ), job engagement ( Harter et al., 2002 ), and reduced career aspirations ( Davies et al., 2005 ).

Stereotype Threat Processes

After many studies established the effects of stereotype threats on various outcomes for several minority groups, research turned to understanding the mechanisms driving these effects ( Schmader et al., 2008 ; Inzlicht et al., 2014 ). Experiencing stereotype threat can lead to a cascade of processes that include attentional, physiological, cognitive, affective, and motivational mechanisms (see Casad and Merritt, 2014 ). When a stigmatized person becomes aware that their stigmatized status may be relevant in a particular context, they may become vigilant and increase attention for environmental cues relevant to potential prejudice and discrimination.

In addition to increased vigilance or attention, stereotype threat causes heightened physiological arousal such as heighted blood pressure and vasoconstriction ( Blascovich et al., 2001 ; Croizet et al., 2004 ; Murphy et al., 2007 ; Vick et al., 2008 ). However, physiological arousal alone does not necessarily lead to negative outcomes, but rather the appraisal of a stimulus as threatening or challenging elicits a response ( Blascovich et al., 2004a , b ; Schmader et al., 2008 ; Inzlicht et al., 2012 ).

Research on stereotype threat processes has identified cognitive and affective factors, particularly cognitive, and affective appraisals, as determinants of outcomes ( Major et al., 2002 ; Major and O’Brien, 2005 ). Cognitive appraisals can heighten awareness of a relevant stereotype, thus reinforcing the arousal of threat ( Inzlicht et al., 2006a ). These cognitions include the extent to which a stressor is self-relevant, dangerous, and creates uncertainty. The negative cognitions initiate physiological arousal, such as elevated cortisol, increased adrenaline, increased blood pressure, and other cardiovascular responses such as increased vasoconstriction ( Chen and Matthews, 2003 ; Blascovich et al., 2004a ; Vick et al., 2008 ). Relatedly, affective appraisals can heighten awareness of a relevant stereotype, thus reinforcing the arousal of threat ( Inzlicht et al., 2006a ). These emotions include feeling overwhelmed, nervous, anxious, worried, and fearful, which initiate physiological arousal like cognitive appraisals ( Chen and Matthews, 2003 ; Blascovich et al., 2004a ).

A final mechanism that explains why stereotype threat can negatively affect performance and spill over into other domains is executive functions. Executive functions are required to self-regulate one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors under stress ( Muraven et al., 1998 ; Muraven and Baumeister, 2000 ). This self-regulation requires not only motivation, but also ego-strength, which comes in limited supplies ( Muraven et al., 1998 ; Muraven and Baumeister, 2000 ). When a task requires a controlled response, willful action can quickly deplete ego-strength, or it can divert motivation and attention to other actions ( Inzlicht et al., 2014 ). Research has shown that women under stereotype threat were quicker to fail at a self-regulation task (squeezing a hand grip—a task irrelevant to math-based stereotype threat) than women not under threat ( Inzlicht et al., 2006b ). Other research shows that participants under threat give up on complex tasks more quickly than participants not under threat (Inzlicht and Hickman, 2005, Unpublished Manuscript). In order to overcome stereotype threat, people have to exert self-control, often having to work harder to maintain performance in the face of threat ( Inzlicht and Kang, 2010 ). Exerting self-control may prevent negative performance at the moment, possibly accounting for null effects of stereotype threat on performance in workplace settings; however, exerting self-control comes at a cost. The stress of working against stereotype threat can spill over into other seemingly unrelated domains such as health (diet, exercise, and alcohol/drug abuse), decision-making, and aggression ( Inzlicht and Kang, 2010 ; Inzlicht et al., 2011 ). Next, we describe four negative consequences of stereotype threat beyond performance.

Reduced Openness to Feedback

Stereotype threat has been shown to hinder affected employees’ openness to and utilization of critical feedback ( Roberson et al., 2003 ). Feedback is vital for an organization’s workforce to adapt and grow, and when employees from stigmatized groups are not able to utilize feedback as effectively as non-stigmatized workers, their chances for advancement and success will be hindered ( Crocker et al., 1991 ).

Employees faced with stereotype threat often find it easy to assume that their coworkers or superiors are biased against them due to their group membership ( Walton et al., 2015a ). This can often occur when a non-minority manager presents negative, though constructive, feedback to a minority subordinate. If the employee is vulnerable to stereotype threat, such as being a numeric minority in the workgroup, they are more likely to interpret negative feedback as internally attributed, such that it speaks to their inherent ability ( Kiefer and Shih, 2006 ). This misattribution increases the vulnerability of self-esteem, so these employees may then be more likely to interpret that negative feedback as biased and discount it ( Roberson et al., 2003 ). Discounting valuable feedback robs the employee of a valuable learning experience and the opportunity to improve their standing or performance ( Roberson et al., 2003 ). A non-minority employee does not undergo this process when interpreting feedback, so they can more easily perceive the feedback as legitimate and utilize it effectively.

The tendency to discount critical feedback has been documented in several studies. Cohen et al. (1999) found that African American students were less likely to adjust written essays that following feedback given by white professors if they were led to believe that white students received less negative feedback. Cohen and Steele (2002) found a similar effect with female science students when giving presentations before and after negative feedback. It is likely that this pattern is due to minority members’ desire to protect their self-esteem from negative information regarding personal performance. Because subtle forms of prejudice are pervasive, it is highly likely for stereotyped individuals to assume that feedback in interracial or mixed gender context might be biased. Therefore, discounting negative feedback to protect one’s self-esteem may be adaptive, reasonable, and justified. Failing to discount biased feedback could potentially reinforce negative stereotypes about belonging and ability ( Crocker and Major, 1989 ; Cohen et al., 1999 ; Walton et al., 2015a ).

Apart from discounting feedback from supervisors, stereotype threat may influence how minority employees seek out feedback concerning their performance. Research has shown that direct feedback, or explicit and outright feedback, is much more effective in terms of improving performance. Conversely, indirect feedback, or monitoring one’s environment for cues about ones performance, is much more ambiguous and therefore less useful ( Ashford and Tsui, 1991 ). An important distinction, however, is that direct feedback can often be perceived as emotionally threatening as it reflects a more true representation of performance. Indirect feedback is much less threatening because the recipient is not confronted about their performance outright ( Ashford and Northcraft, 1992 ). In order to protect social standing and avoid public scrutiny, minority employees may actively avoid direct feedback ( Roberson et al., 2003 ).

Reduced Domain Identification

Chronic exposure to threat may lead stigmatized individuals to disidentify from the domain in which they are negatively stereotyped ( Steele and Aronson, 1995 ). Disidentification serves as a coping mechanism to chronic threat where individuals selectively disengage their self-esteem from intellectual tasks or domains ( Steele, 1992 , 1997 ; Crocker et al., 1998 ). That is, by redefining their self-concept to not include achievement in that domain as a basis for self-evaluation, individuals protect their self-esteem so that poor performance in that domain is no longer relevant to their self-evaluation. However, disidentification is a maladaptive response, and it is a contributing factor to reduced career and performance goals ( Major and Schmader, 1998 ) and workplace turnover ( Crocker et al., 1998 ; Harter et al., 2002 ).

Another area of concern is that stereotype threat interferes with minorities’ ability to integrate personal identities with professional identities. When employees view their personal identity (e.g., woman, African American) as incompatible with their professional identity (e.g., lawyer) because of stereotype threat in the workplace, negative mental health consequences are likely ( Settles et al., 2002 ; Settles, 2004 ). Female lawyers, accountants, and managers who experienced stereotype threat reported separating their identity as a woman from their professional identity ( von Hippel et al., 2010 , 2011a , 2015 ). Other research shows that women scientists report having to switch back and forth between their identity as a woman and identity as a scientist in order to fit into male-dominated environments ( Settles, 2004 ). Adverse consequences of this lack of identity integration include negative job attitudes ( von Hippel et al., 2011a ), more negative work-related mental health ( von Hippel et al., 2015 ) greater depression ( Settles, 2004 ), lower life satisfaction ( Settles, 2004 ), and reduced likelihood of recommending fellow women to the field (e.g., finance; von Hippel et al., 2015 ).

Reduced Engagement

Another non-performance consequence of stereotype threat is the tendency for stereotyped individuals to disengage from their work tasks and the feedback that follows. Employees under threat may disengage in order to distance their self-esteem from the potential consequences of their work performance ( Major and Schmader, 1998 ). If a particular stereotype indicates that the individual will perform poorly, that individual is more likely to reduce their attachment to their performance for fear of potentially proving that stereotype correct. This process leads to feelings of powerlessness ( Major et al., 1998 ). Stigmatized individuals therefore reduce the amount of care and concern they put toward a work outcome in order to avoid the negative consequences of their anticipated poor performance. Individuals who identify highly with their domain are most susceptible to disengagement, since success in that domain is more central to them, making negative feedback much more damaging.

Disengagement is closely related to disidentification in that repeated disengagements often contribute to the individual reducing their identification with a certain domain. Disengagement is typically a state-level phenomenon that occurs in response to specific situations, such as analyzing scientific data, whereas disidentification is typically a chronic state that affects the individual’s overall identity attachment to the domain, such as being a scientist. If the individual regularly disengages from relevant tasks in order to shield his or her self-esteem, a reduction of identification to the domain could result. This cycle is problematic, as it indicates disengagement can ultimately result in higher turnover due to a lack of domain identification ( Crocker et al., 1998 ; Harter et al., 2002 ).

Disengagement has been shown to negatively impact task performance and motivation, such that individuals will give up more easily on a stereotype-relevant task while under threat ( Crocker and Major, 1989 ; Steele, 1992 ; Major and Schmader, 1998 ). Research indicates it is not the task itself that is threatening, but rather the anticipated feedback that follows ( Ashford and Tsui, 1991 ). If employees under threat are highly engaged in their work, and they receive negative feedback that aligns with a relevant group stereotype, it could be much more damaging to their self-esteem than it would be for non-threatened employees ( Major and Schmader, 1998 ).

Disengagement results from discounting and devaluing. Discounting occurs when the employee dismisses feedback as an invalid representation of one’s potential due to external inadequacies, such as skepticism toward an intelligence test. Devaluing occurs when the employee dismisses the importance of the feedback, often taking the position that the feedback does not matter to them or their career path. When stereotyped individuals engage in discounting and devaluing, negative feedback is less likely to affect self-esteem because the feedback has been deemed irrelevant or flawed ( Major and Schmader, 1998 ).

Interestingly, there has been a small body of research investigating the potential adaptiveness of disengagement. For example, Nussbaum and Steele (2007) observed that temporarily disengaging from harmful feedback can actually foster persistence, as it deflects damage to the self-esteem which would otherwise create a sense of lack of belonging. While it is possible that situational disengagement could be beneficial in particular contexts, it cannot be harnessed and applied to particular contents of the individual’s choosing – it is evoked whenever the individual feels threatened. Additionally, disengagement, regardless of its capacity to protect self-esteem, results in the rejection of valuable feedback that could otherwise be used toward refining work-relevant skills. Finally, chronic disengagement has been shown to lead to disidentification, or no longer perceiving one’s workplace identity as central to self-identity ( Crocker et al., 1998 ), which in turn is associated with increased turnover ( Harter et al., 2002 ). It is therefore critical that disengagement is curtailed, and reducing stereotype threat is necessary to do so.

Reduced or Changed Career Aspirations

Another consequence of chronic experiences with stereotype threat is reduced or altered career aspirations. When people feel threat in a domain, they often feel they have fewer opportunities for success in the domain ( Steele, 1997 ). For example, Davies et al. (2005) found that women were less interested in taking on leadership roles after viewing gender stereotypic television commercials. Similarly, when leadership roles are described using masculine traits, women report less interest in entrepreneurship than men ( Gupta et al., 2008 ). Reduced career aspirations in response to threat, particularly for women in leadership, entrepreneurship, and science may exacerbate the gender gap in these fields ( Murphy et al., 2007 ; Koenig et al., 2011 ).

Consequences of Stereotype Threat for Organizations

As previously outlined, stereotype threat leads to a cascade of mechanisms that can lead to poor performance in a stereotyped domain, or spillover into unrelated domains such as health. In the previous section we described research documenting how stereotype threat can result in reduced openness to feedback from employers, reduced domain identification, reduced job engagement, and reduced or altered career aspirations. All four of these consequences are linked to changes in behaviors that have consequences for the workplace. Experiencing stereotype threat has shown to impair leadership performance and aspirations, negotiation skills, entrepreneurial interests, and skills, and desire to work in competitive environments and competiveness skills ( Kray and Shirako, 2012 ). The following section describes predominantly lab-based research that shows the negative effects of stereotype threat on these four important workplace behaviors.

Encountering stereotype threat has been shown to limit one’s willingness to embrace challenges and work through uncertainty because any resulting failure could be interpreted as evidence supporting the stereotype ( Steele, 1997 ). Experiencing stereotype threat leads individuals to avoid domains in which they are stereotyped as not belonging, such as women in leadership. Leaders are commonly assumed to be white males ( Koenig et al., 2011 ), therefore women and racial minorities seeking leadership positions must directly challenge that stereotype. Empirical evidence has supported the idea that when individuals face stereotype threat, they are less likely to pursue leadership roles, particularly when they are the only member of their group among their peers ( Hoyt et al., 2010 ). It is assumed that the threatening environment activates a heightened aversion to risk, which when coupled with greater uncertainty regarding their success, may cause them to forgo challenges such as striving for leadership roles.

Aligning with this theory, Davies et al. (2005) instructed women to choose to hold either a leadership or non-leadership position following the presentation of either a stereotype-activating commercial or a neutral commercial. Results indicated that women who viewed the stereotype-relevant commercial were more likely to elect to hold the non-leadership position, whereas those who viewed the neutral commercial were more evenly distributed between the two roles. This indicates that the knowledge and activation of stereotypes of women’s roles as subordinate or supportive in nature rather than leadership roles will diminish women’s desire to lead due to the fear of confirming the stereotype. This phenomenon is even more dangerous because it can activate a self-perpetuating cycle – stereotyped individuals avoid leadership roles due the stereotype that leaders should be white males, which then discourages those individuals to establish a prominent leadership presence. When no female or minority leaders are present, no information counter to the stereotype is available and the stereotype persists.

It is important to note that individual differences can diminish the effects of stereotype threat on leadership aspirations. For example, for women who are already high in leadership self-efficacy, the presence of stereotypes can actually motivate them to pursue leadership positions and increase their identity as a leader ( Hoyt, 2005 ). Research has shown that identity safety can mitigate the effects of stereotype threat ( Markus et al., 2000 ), meaning security with one’s identity can increase a feeling of belonging in that particular domain. Stereotyped individuals can therefore view the stereotype as a challenge rather than a threat and feel less uncertainty regarding future success. One issue, however, is that establishing leadership self-efficacy often requires past performances that were successful ( Bandura, 1977 ), which means that in order for leadership self-efficacy to be high enough for stereotyped individuals to challenge stereotypes, it may be necessary for them to have proven their capability as a leader at an earlier time.

Entrepreneurship

Paralleling the reduced aspiration to participate in leadership roles, the presence of stereotype threat can also inhibit individuals from pursuing entrepreneurial endeavors. Many traits that are important for leaders are also important for entrepreneurial success (e.g., assertiveness, risk-taking), thus similar hesitations can result. Although it appears that the number of female entrepreneurs is growing in industries such as retail and personal service ( Anna et al., 2000 ), this is presumably because those industries still center on female-oriented traits such as nurturance, sensitivity, and fashion-sense. Even with this increase, however, the number of male entrepreneurs still outnumbers that of female entrepreneurs 2 to 1 ( Acs et al., 2005 ).

When stereotype threat is due to contextual or situational cues, individuals can strive to eliminate the threat by distancing themselves from that situation or context. Because masculine stereotypes are important for entrepreneurial success, women may negatively evaluate their capability for success and therefore distance themselves from any entrepreneurial endeavor. Although some research has shown that proactive personalities can buffer the effect of stereotype threat on women’s entrepreneurial intentions ( Gupta and Bhawe, 2007 ), activating stereotypes of entrepreneurship and masculinity discourages women from taking such risks.

Negotiations

Many of the stereotypic masculine traits mentioned previously can impact aspects of the workplace other than career aspirations and risk-taking. Because strong negotiators are stereotyped to have masculine qualities, women may alter their negotiation strategies. Much of this research is similar to other areas, namely that activating gender stereotypes can cause women to underperform during negotiations compared to when stereotypes are not activated ( Kray et al., 2002 ). Stereotype threat also leads to less willingness to initiate a discussion that is negotiative in nature Small et al. (2007) .

The dynamic nature of negotiations makes it challenging for researchers to determine whether gender differences in negotiation performance are due to the suppressed performance of women under threat, or the situational control experienced by male opponents ( Kray and Shirako, 2012 ). Although research suggests the mere competitive nature of the negotiation process is what deters women from pursuing maximum benefits ( Gneezy et al., 2003 ; Niederle and Vesterlund, 2010 ), several studies show women’s negotiation performance improves when stereotypes are made explicit ( Kray et al., 2001 , 2004 ). This phenomenon is due to stereotype reactance, or the tendency to react counter to a stereotype when overt attention is drawn to its unfairness. However, if a stereotype is presented implicitly, women’s performance may still be negatively impacted ( Kray et al., 2001 ).

The negative effects of stereotype threat on negotiations does not necessarily stop at the bargaining table. Research has shown that women who behave in ways counter to gender stereotypes may be faced with social backlash ( von Hippel et al., 2011b ), especially if interactions with the negotiator are expected to recur. This suggests that even if women are able to overcome stereotype threat and negotiate effectively in a particular situation, the chronic experience of stereotype threat can potential impact women throughout their careers.

Competitiveness

As previously mentioned, one reason women may be less effective in leadership, entrepreneur intentions, and negotiations is a dislike of competitiveness. Competitive environments can be threatening to women due to the stereotype that women cannot fend for themselves when competing with men, and that they are better suited for supportive roles. Gneezy et al. (2003) conducted an experiment where participants were instructed to complete a computerized maze to earn compensation. Participants were either compensated for every maze completed regardless of performance or only if they solved the most puzzles in a set amount of time. Results indicated that men’s and women’s performances did not differ in the non-competitive condition, but women’s performance was significantly lower in the competitive condition. In the competitive condition, women elected not to dedicate effort to compete due to a preconceived expectation of losing. This parallels the idea that women may not feel capable of performing well in competitive environments, and therefore do not fully engage themselves, which can protect their self-esteem following expected loss ( Gneezy et al., 2003 ).

People who lack a competitive nature may experience difficulties in the competitive world of work. Stereotypes that give men a competitive edge (e.g., men play sports while women cheer them on) can carry over into a wide array of workplace contexts, potentially leaving women feeling unprepared, or incapable of competing. Although some research shows that women are capable of competitiveness on tasks in which women are more knowledgeable ( Günther et al., 2010 ), this stereotypical gender difference still gives a normative advantage to males across most situations. In a workplace, whether it be for a position, client, project, or ethical dilemma, having the ability and motivation to compete with others may determine success or failure. Understanding this phenomenon and equipping women with strategies to be competitive in the workplace is of vital importance.

Stereotype Threat Interventions in the Workplace

Broadly speaking, stereotype threat research is typically divided into three subdivisions – whether stereotype threat is present in a given domain, whether its presumable effects can be prevented or reduced, and the underlying mechanisms of the effects. All three types of research are necessary – there is no use preventing it if its effects are nonexistent, but no change will ever occur if we do not first understand why it is happening and then develop strategies to overcome it. Research has come a long way in developing intervention strategies, and there now exists a wide variety of interventions that organizations can implement in order to reduce stereotype threat and its effects on employees.

One issue concerning these interventions raised by researchers and organizational leaders is that many of the strategies, while sound in theory and laboratory testing, are not always applicable or practical in real-world practice, and therefore are not helpful to organizations ( Streets and Major, 2014 ). For example, one well-known intervention strategy within the stereotype threat literature is to increase minority representation within the organization ( Purdie-Vaughns et al., 2008 ; Spencer et al., 2015 ). Doing so has been shown to not only increase the value placed on diversity, but has also aided in the development of role models—a strong antecedent for the success of stereotyped individuals ( Marx and Roman, 2002 ). While this practice is undoubtedly effective, reorganizing personnel or modifying hiring practices requires major organizational change and expense. This intervention may not be attainable, particularly for smaller companies with fewer resources and opportunities to hire new personnel.

It seems the main argument against implementing stereotype threat interventions in the workplace is cost and potential disruption to the work environment. In the next section we describe intervention strategies that are no or low cost that can be integrated into existing training programs. Ultimately the organization has to weigh the costs and benefits of implementing workplace interventions. However, continuing to ignore diversity issues in the workplace and having employees who experience stereotype threat may negatively impact organizations’ bottom line in unanticipated ways (e.g., higher turnover, burnout, lawsuits).

Stereotype threat is triggered by subjective interpretation of situational contexts, which makes perceptions malleable through interventions. Interventions target institutional, structural level features of the organization and also individual level factors related to subjective construals of environments ( Cohen et al., 2012 ). Effective interventions range from brief, low-cost interventions such as changing physical workplace environments to long-term, high-cost changes such as diversifying the workforce. In this section we describe a range of stereotype threat reducing interventions that have been tested in laboratory and field settings, which are summarized in Table 1 .

Institutional and Structural Level Interventions

Addressing environmental cues.

Research has documented several environmental cues that can trigger stereotype threat, thus employers can be proactive in minimizing the presence of these cues in the workplace. Regarding the physical workplace environment, décor can signal to employees, and prospective recruits, whether they are welcomed in the organization. For example, halls decorated with photos of senior management and executives that represent Caucasian males may trigger doubt that women and minorities can advance in the organization. Other seemingly benign objects, such as the choice of magazines in a reception area, can affect the perception of the organization’s diversity values ( Cohen and Garcia, 2008 ). Do the magazines reflect a diversity of tastes and are they targeted to diverse audiences? Décor that communicates a masculine culture, such as references to geeky pop culture, may signal to women and those who do not identify with these cues that they do not belong ( Cheryan et al., 2009 ).

Research has shown that perceptions of environments are not limited to physical workspace. Websites, employment offer letters, and virtual environments have all been shown to evoke similar appraisals of belonging, potential threat, and person-organization fit to that of physical environmental cues ( Ng and Burke, 2005 ; Braddy et al., 2006 ; Cheryan et al., 2011 ). The design and content of websites, language used in various materials, and presence of stereotypes in virtual settings all have the potential to signal to diverse applicants and employees that they do not belong ( Walker et al., 2012 ). If organizations portray a particular culture through virtual or nontraditional avenues, and that culture could be considered threatening to women, such as one that values taking risks or that is highly competitive, the favorability of the organization from a woman’s perspective could be negatively affected. Conversely, if an organization is able to communicate an appreciation and acceptance of diversity, such as including a demographic variety in their testimonials, images, and recruiters, women’s and racial minorities’ perceptions of the organization could be bolstered ( Braddy et al., 2006 ).

Organizational research has also shown that a stereotype-affirming environment leads members of stereotyped groups to question their belonging to that workgroup ( Elsbach, 2003 ). Women in technology perceived greater threat when working in environments that they felt were masculine in nature. When in environments that are subtly (or not so subtly) favorable for men, it may induce women to feel that they are infiltrating a “boy’s club,” and that they must accept the existing social norms. Physical markers within an environment include things such as masculine wall colors, breakroom paraphernalia such as calendars or refrigerator magnets, or a norm of vulgar language. Making the physical environment, particularly common areas such as the breakroom and lobby, more gender neutral will help to dispel the feeling that the organization favors one gender group over the other.

In sum, employers should scrutinize physical and virtual workplace environments and messages to ensure that these cues are communicating the intended message that all employees are valued and belong.

Valuing Diversity Among Employees

A more pervasive environmental cue is lack of racial, ethnic, age, and gender diversity among employees. Being a numeric minority in an evaluative context such as the workplace is sufficient to trigger stereotype threat ( Inzlicht and Ben-Zeev, 2000 ; Murphy et al., 2007 ). For example, women college students viewed one of two videos depicting a science conference. Those viewing the video in which women were underrepresented 3:1 were less interested in attending the conference, anticipated feeling a lack of belonging at the conference, and showed a cardiovascular threat response to watching the video compared to women who watched a gender balanced video ( Murphy et al., 2007 ).

Research on solo status documents the negative effects of being the only or one of few members of a racial or gender group in the workplace ( Saenz and Lord, 1989 ; Sekaquaptewa and Thompson, 2003 ). Numeric minorities can feel pressure to positively represent their group and engage in counter-stereotypic behavior ( Saenz and Lord, 1989 ; Sekaquaptewa and Thompson, 2003 ); however, members of majority groups often attribute minority group members’ behaviors as confirming a negative group stereotype ( Sekaquaptewa and Thompson, 2003 ). A non-diverse workforce can elicit mistrust and less commitment from minority employees ( Roberson et al., 2003 ; Purdie-Vaughns et al., 2008 ).

Another reason a non-diverse workforce is problematic is there are fewer ingroup members to serve as role models for members of minority groups. Having a same-race or same-gender role model is beneficial for employees’ achievement and motivation in the domain ( Dasgupta and Asgari, 2004 ; McIntyre et al., 2011 ). If ingroup role models are not available, merely presenting members of underrepresented groups with stories of successful minority role models is effective in reducing stereotype threat ( von Hippel et al., 2010 ).

Although diversifying an organization’s workforce is the ideal solution, this may not be feasible in the short-term, particularly for smaller organizations. A possible remedy for lack of a diverse workforce is the organization’s diversity philosophy or mission. Although the organization may not have a very diverse body of employees, this does not prevent the organization from communicating its value of diversity to current and prospective employees. Research has investigated three types of diversity philosophies and their effects on minority and majority group’s perceptions of the organization, including color-blind, multicultural, and all-inclusive multicultural ( Plaut et al., 2009 ). Although a color-blind policy indicating race does not affect performance or evaluations and employees are valued for their work ethic seems positive, this widely endorsed policy is viewed as exclusionary by minorities ( Plaut et al., 2009 ). Often a color-blind approach results in valuing a majority perspective by ignoring important group differences and overemphasizing similarities ( Ryan et al., 2007 ), which can in turn trigger stereotype threat ( Plaut et al., 2009 ). In contrast, a multicultural philosophy values differences and recognizes that diversity has positive effects in organizations ( Ely and Thomas, 2001 ). Minority groups report feeling more welcome when organizations have multicultural policies ( Bonilla-Silva, 2006 ); however, majority groups have reported feeling excluded ( Thomas, 2008 ). More recent research suggests an all-inclusive multicultural approach is most effective. This approach recognizes and values contributions from all groups, majority and minority, and all employees report feeling included with this philosophy ( Plaut et al., 2011 ).

Organizational behaviors that communicate the adoption of a multicultural philosophy are often based on awareness and sensitivity. For example, the creation of a specific position responsible for managing diversity issues can better equip the organization to address diversity-related concerns. Diverse employees who are potential candidates for promotion could be identified and targeted in the promotion process. Turnover rates for diverse employees could be specifically analyzed and interpreted. Organizations can implement training with all employee ranks that stresses the value of a diverse workforce ( Blanchard, 1989 ; Konrad and Linnehan, 1995 ). There are numerous strategies that organizations can undertake. Research has shown that the adoption of multicultural practices such as these leads to attracting and retaining highly qualified diverse applicants ( Ng and Burke, 2005 ; Brenner et al., 2010 ), the subsequent hiring of more qualified diverse applicants ( Holzer and Neumark, 2000 ), and greater organizational commitment among diverse employees ( Hopkins et al., 2001 ). Conversely, if applicants perceive the organization is not welcoming of racial and ethnic diversity, they may be less likely to pursue employment with that organization ( Purdie-Vaughns et al., 2008 ).

Wise Feedback and Organizational Mindset

As discussed previously, a negative consequence of stereotype threat is discounting feedback ( Roberson et al., 2003 ), which hinders employee’s professional development and performance in the organization. Members of minority groups are particularly likely to mistrust feedback when it is in interracial or intergender contexts ( Cohen et al., 1999 ; Cohen and Steele, 2002 ). A negative consequence for those giving critical feedback is the feedback withholding bias ( Harber, 1998 ). Because giving and receiving critical feedback is important for individuals’ and organizations’ performance, employers should be trained in how to give “wise feedback” ( Yeager et al., 2013 ). Wise feedback has the goal of clarity, to remove ambiguity regarding the motive for the feedback so that members of minority groups do not attribute negative feedback to racial or gender bias. In this approach, the supervisor communicates to the employee that he or she has high standards for the employee’s performance but that he or she believes the employee can live up to those standards. When framed in this manner, the purpose of the feedback is to help the employee meet the high standards. Field studies show that minority students given wise feedback showed more motivation to improve ( Cohen et al., 1999 ) and were more likely to resubmit their graded work after receiving feedback ( Yeager et al., 2013 ).

The role of communicating high standards in wise feedback is also reflective of organization mindsets. Research on entity and incremental views of intelligence ( Dweck, 2006 ) has documented that how educators and employers, communicate their beliefs about intelligence and performance affects students’ and potential employees’ motivation and performance ( Murphy and Dweck, 2010 ). An entity or fixed mindset reflects beliefs that intelligence is something humans are born with and that the capacity to increase intelligence occurs within innate boundaries. This mindset promotes viewing mistakes and challenges as evidence of low intelligence. In contrast, an incremental or malleable view of intelligence suggests that intelligence is a result of learning and hard work and that anyone can increase their intelligence. In this mindset, mistakes are viewed as an important part of the learning process. Research with adolescents ( Paunesku et al., 2015 ), girls ( Good et al., 2003 ), and racial minorities ( Aronson et al., 2002 ) struggling with math shows that incremental mindsets predict learning and achievement. Recent work has documented that organizations perceived to have fixed mindsets elicited more stereotype threat among women ( Emerson and Murphy, 2015 ). Organizations perceived to have a growth (incremental) mindset did not elicit threat and women reported greater trust and commitment to the organization and had higher performance ( Emerson and Murphy, 2015 ).

In sum, supervisors should be trained in giving wise feedback. Organizations should communicate to current and prospective employees the value placed on motivation, hard work, and effort. New hires are selected in part for their competencies, thus emphasis on effort will keep employees motivated to perform well and may reduce or eliminate stereotype threat ( Murphy and Dweck, 2010 ; Emerson and Murphy, 2015 ).

Individual and Psychological Focused Interventions

Reattribution training.

One way that employers can empower employees to avoid experiencing stereotype threat is through reattribution training, or attribution retraining ( Walton and Cohen, 2007 ). When facing challenges common in the workplace, employees who attribute hardships to temporary, external factors are more likely to excel in the face of failure than employees who attribute setbacks to internal factors such as ability ( Weiner, 1985 ). Research has shown that providing alternative explanations for the perceived difficulty of a task can allow individuals the opportunity to attribute that difficultly to something other than their stereotyped group membership ( Wilson et al., 2002 ). Providing alternative explanations may help to alleviate some of the anxiety caused by stereotype threat because it buffers self-esteem from negative self-evaluation.

Research shows that reattribution training can be effective when inadequate instructions or guidelines are offered ( Menec et al., 1994 ), employees lack practice or experience on a given task ( Brown and Josephs, 1999 ), and the work needs to be carried out in an irregular context ( Stone et al., 1999 ). These alternative explanations for poorer performance reflect external and less controllable circumstances, thus group membership is no longer the only plausible explanation for shortcomings in performance. The individual can now partially attribute performance to factors not associated with self-esteem.

To illustrate this technique, consider the following scenario. During the onboarding process, employers can share stories with new employees about others’ experiences when first joining company. For example, highlighting cases where individuals first felt like an outsider, but then developed a sense of community after joining an organization-related club. When a new trainee experiences difficulty learning a new job skill, the trainer can emphasize that other new employees experienced initial trouble but mastered the skill after practice, which will diffuse the negativity of the setback. However, attribution retraining is only successful when the employee is provided with the opportunity to grow and learn from their mistakes ( Menec et al., 1994 ). Employers who wish to implement this intervention should consider the training opportunities available to new and current employees and expand resources as necessary to support development opportunities.

Attribution retraining must not be confused with simply providing plausible excuses for employees or lying to employees about why they may have failed. Additionally, attribution retraining should not give employees a guilt-free outlet for regular underperformance. Rather, the goal of attribution retraining should be to remind employees of any existing difficult circumstances which may be stalling performance, not create them ( Roberson and Kulik, 2007 ). Therefore, managers ought to utilize this strategy only when the following criteria are met: (1) when a stereotyped employee is presumably struggling due to stereotype threat; (2) when actual difficult circumstances may be preventing employees from succeeding; and (3) when underperformance is understandable and not crucial to typical job performance. Meeting these criteria will insure that attribution retraining is targeted at combating stereotype threat among truly capable employees. Although attribution retraining will not target the source of stereotype threat, it may provide additional resources to employees who are having trouble coping with it.

Reframing the Task

One way in which stereotype threat can be actively removed from an evaluative performance situation is by simply reframing the task—that is, by using a description that does not evoke negative stereotypes about a social group. Although diagnostic exams and workplace evaluations activate stereotype threat implicitly, explicitly describing an exam or evaluation as non-diagnostic (for example, of intelligence) is enough to eliminate the effects of stereotype threat ( Steele and Aronson, 1995 ). However, this method does not seem practical in diagnostic exams, such as standardized tests, that are meant to measure an individual’s academic performance. Research has also found that stereotype threat can be eliminated by explicitly stating that exams show no difference in performance based on stereotypes. For example, describing a math exam as gender-fair can be enough to dramatically increase women’s math performance ( Spencer et al., 1999 ; Quinn and Spencer, 2001 ). This method is quite practical because simply stating the gender and cultural fairness of an exam before it is administered can easily reduce stereotype threat effects. In a workplace setting, describing evaluations as objective or fair may alleviate stereotype threat ( Kray and Shirako, 2012 ). That is, if an evaluation is conducted by more than one supervisor and focuses on behaviors and quantitative metrics of performance, evaluations may be less biased and may not evoke threat ( Austin and Villanova, 1992 ; Bommer et al., 1995 ). Employers should evaluate testing or evaluation procedures to make sure the fairness of the metric is communicated to employees.

Values-Affirmation

An intervention that can reduce stereotype threat and improve performance is values-affirmation ( Sherman and Cohen, 2006 ; Sherman and Hartson, 2011 ). The intervention is based on self-affirmation theory, which states that affirming an aspect of the self that is valued and unrelated to a particular threat can buffer self-esteem and alleviate the threat ( Sherman and Cohen, 2006 ). Value-affirmation interventions have been implemented in school settings, typically having students write for 15–20 min about things that they value and why, often including this as a regular writing assignment throughout the academic term. This helps to put students’ troubles in the broader context of their values and sources of support. This brief, low-cost intervention has shown to improve minority students’ GPA even 3 years later ( Cohen et al., 2009 ; Sherman et al., 2013 ). It also has reduced stereotype threat and increased sense of belonging among minorities ( Cohen et al., 2009 ; Sherman et al., 2013 ) and women in the sciences ( Walton et al., 2015a ). Research suggests the key mechanism for values-affirmation interventions is to have participants write about social belonging ( Shnabel et al., 2013 ).

Recent research has applied values-affirmation interventions in the workplace and found improved performance and retention ( Cable et al., 2013 ). Cable et al. (2013) encouraged employees of a large international organization to express their “best selves,” in that they encouraged their employees not to censor or withhold their input or perspectives. This communicated to the employees that all inputs were valued and important, and resulted in decreased experiences of stereotype threat among employees. Wiesenfeld et al. (1999) simulated an organizational layoff, in which a confederate was unfairly excused from further participation in the experiment. Results indicated that witnessing the unfair treatment, which is theorized to threaten self-integrity, inhibited performance on a subsequent task. Conversely, when the layoff was perceived as fair, participants were less likely to report self-consciousness as opposed to the unfair condition. In other words, when affected employees perceive a threat to their self-esteem, they alter how they evaluate themselves and exhibit performance detriments.