- Safety and Security Solutions at School Words: 549

- Public and Private Schools: Comparing Words: 1170

- High School Students and Vocational Education Words: 2266

- Why High Schools Are the Way They Are? Words: 1438

- School Safety and Gun Violence Prevention Words: 620

- Arts Education and Its Benefits in Schools Words: 729

- Education in High School Versus College Words: 879

- School System: Poverty and Education Words: 598

- Education System in the United States Words: 8165

- Should Schools Distribute Condoms? Words: 1358

- Schools Voucher and Competitive Choice Words: 1559

- Charter Schools Impact on the US Educational System Words: 2064

- Traffic Situation and Safety Concerns in Saudi Arabia Words: 4520

- Should US Public Schools Have a Longer Year? Words: 945

- The Problem of Prayer in School Words: 1131

- School Experience for Students with Disabilities Words: 967

- Whole School Approaches to Supporting Student Behaviour Words: 2538

- Education Gap in “A Tale of Two Schools” Video Words: 564

- American School Uniforms and Academic Performance Words: 1134

- Road Safety Precautions for Drivers Words: 997

Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level

Introduction, current trends, young people and driving, the graduated licensing system, special niches for school traffic education, works cited.

Traffic safety education at the school level is meant to provide the students with lifetime skills for maneuvering in the public roads and highways. The importance of learning these skills at school level is increasing, since more and more students are nowadays driving to school. Those not driving are riding either bicycles or motorcycles. All of these kinds of students need to be provided with special education on their safety and the safety of other road users when they are on the road. Traditionally, this has been integrated into the school systems, and students have benefited from them. The last ten years have shown a marked reduction in overall traffic accidents and fatalities.

But with the ongoing financial crisis, the rules are changing. What was previously treasured for its invaluable contribution to the safety of the general public is now being regarded only in terms of its budgetary requirements. And, in the backdrop of what is regarded as more crucial needs, traffic education in school has slowly begun to be discarded. There is simply no luxury budget to accommodate this course. This says something about the financial priorities within Washington. Perhaps the information divulged herein will serve to persuade all concerned bodies that continued support for the driving program is critical.

Observations show that more and more students are being enrolled into secondary schools having reached the legal driving age. There are several reasons for this. For one, more students are completing year 12 of learning. Secondly, there is an increase in the number of students who are commuting between school and work as part-time students. Then lastly, the number of students who live independently from their parents has increased considerably. These factors, combined, have resulted in a marked increase in the total number of students driving to school.

Besides the students already driving to school, there is a huge majority of other young people who, daily, have to grapple with the ever increasing traffic snarl ups. These young people need to be able to maneuver their way through the traffic of the cities, and any knowledge they may have about safety comes to play then. Withdrawing a course that teaches them how to survive in the highways then is like denying them a chance to exercise their rights on the roads. After all, if the young people don’t know their rights, they aren’t likely to defend them, even when they are clearly taken advantage of by other road users. For example, pedestrians have fundamental rights. Without knowledge of these rights, they can easily be mistreated on the roads without any legal recourse.

Now young drivers show a conscious attempt at driving carefully. They have an inherent need to prove that they can handle themselves on the highways. They are also likely to be more observant about any changes within the environment out and within the car. But despite this, their relative inexperience and certain habits derived from their youthful culture make them some of the most vulnerable driver groups. In addition, they pose higher risks of crash accidents when they travel as groups in the cars. Overall, young drivers in their first year of driving are thrice as likely as experienced people to suffer from road accidents (TAC, 2004). In fact, the most significant cause of death amongst young people between 15-25 years is road accidents.

There are several reasons why young people are at high risk of road accidents. As already said, they are inexperienced. This particular factor is compounded by the fact that most of them tend to perceive themselves as more competent than they actually are. Hence, they tend to take more risks when driving. They, on average, tend to drive for long distances, disregarding road and environmental conditions, and even their own physical conditions like exhaustion. Most of them are also driven by sensation-seeking motivations. Young people carrying other passengers have in particular been observed to be more likely to get involved in accidents. All these factors make these young drivers potential hazards, as long as they are ignored by the education system.

According to statistics gathered during 2006 and 2007, young people have the highest fatalities resulting from road accidents. The 21-30 age group leads with a fatality rate of 21.5%. They are followed by the 15-20 year olds at 16.2% (Mischelle, 2008). The only other age group that even comes close to these fractions is that of people above 74 years old, and these have been explained away by the fact that they are more likely to die from an accident that a younger person would survive. These statistics only emphasize the critical need for formal education on driving by the young people. If ignored, the figures may increase to unprecedented levels, what with the ever faster but more fragile cars coming out of the production lines.

Traffic education should not be considered to be any different from any of the other subjects taught in schools nowadays. If anything, due to its immediate and critical application on our highways, it probably should attain an even higher status than some other conventional subjects. And if it were to be thus integrated into the education structure, then the prevailing laws should see to its satisfactory funding. This is because article 9, section 1 of Washington State Constitution clearly shows the paramount responsibility that the state has towards providing ample provisions for the education of all children residing within that state (Margaret, N.D.). In other words, were traffic education mainstreamed into the curriculum, the state would be obliged to provide funding for it.

The details of the Washington State Constitution article clearly place upon the legislature the powers to define a public school, and any crucial courses within it. Additionally, the public schools thus identified are supposed to be funded through state, not local, funds. Thus, public schools benefited from a full funding by the government. While this was definitely well-intentioned, it also placed a huge load on the state funds. The load increased further when the state was made, through a court act, to fully support even the handicapped, bilingual and remedial students. Some public transport costs for the students in these schools were also included in these responsibilities (Margaret, N.D.). With such a load, the state resources have for a long time been tittering on the edge. The ongoing financial crisis was the last straw. Perhaps, with better foresight, better allocation of resources to the education system could have been implemented. Then critical part of the education like traffic studies would not have to be eliminated.

With the credit crunch and the need to keep road accidents in check, new and revolutionary ideas are being hatched. Some states have instituted regulations that seek to reduce the number of accidents from young people. For example, Washington has a graduated licensing system whereby the young person gets awarded a learner’s license first, then an intermediate license, and finally the full license. Award of these sequential licenses is based on age and experience of the young driver. However, these regulations are at a significant disadvantage due to the fact that a driver’s age can only be ascertained if he or she is pulled over by the roadside for a close checkup. This is a time consuming exercise, and rarely implemented fully (Mathew, 2006). Thus, even while these regulations are in place, they don’t work as well as they ideally should. Their efficacy would be greatly increased if traffic education continued to be taught in schools.

Another reason why traffic safety education should continue within schools is that conditions keep changing out there in the highways. The laws governing drivers within specific states keep on being modified. Having a formal way by which the students can be alerted of these changes within the schools can mean the difference between life and death in some instances. For example, in 2007, Washington Traffic Safety Commission instituted a law restricting the speeds of cars moving near schools, in a bid to reduce fatality through road accidents. At the same time, they put up flashing yellow beacons as an effective way of reducing speeds by motorists (WTSC, 2007). This was done in light of the fact that children below 13 years usually have problems judging distance and speed of approaching cars. Without a formal way of being informed of such events, student drivers may be at a distinct disadvantage, and may continue to pose road hazards, unwittingly.

An area rarely covered by conventional traffic rules is passenger safety. This refers to the safety of everyone within a car who is not presently driving. With the increasing means of motor transport, both private and public, young people are increasingly engaging in dangerous behaviors when being transported as passengers. A huge fraction of young people involved in accidents are found not to have worn safety belts, and even to have been engaging in risky activities within the car (Leonard, 1991). More often than not, these behaviors are influenced by peer pressure. A formal system by which these traits can be eradicated needs to be instituted and maintained, and this can best happen within a school system. There, even excursions can be organized for the students to be taught practically about these regulations and their importance (Peter, N.D.).

Significant fractions of the young people ride bicycles, either for recreation or as a way through traffic. However, some of these young cyclers don’t know the laws governing them as cyclists, and sometimes aren’t even competent on the bicycles. Their ignorance on any of these fronts can easily become fatal, unless they get exposed to a formal way of learning the vital information. Hence within the traffic education structure, there should be a provision for cyclists, who should initially train within the school compound before being allowed to venture into traffic. The experience gained during this period will prove useful even later when the students get to drive cars (Peter, N.D.)

Traffic education, when integrated within the school curriculum, can be made to have a pre-license phase. This phase is distinct from the conventional traffic education in the sense that the student is not taught how to drive or ride. Instead, the individual attitudes and decision-making abilities of the students are shaped to conform to the standards needed on the highways (Peter, N.D.). Hence, in a sense, this pre-license education is more theoretical than applied, but its importance in the overall well being of the student in traffic can not be denied.

Studies all over the world show that the highest fraction (about 74%) of all road accidents is caused purely by human factors like negligence, drunkenness and so on. Environmental factors come a distant second at 14.5%, and vehicle factors are the least contributing of the three at (10.2%). The environmental factors include daylight, lack of adequate pedestrian space and rush hour traffic. Vehicle factors are mainly faulty brakes and tires (Vogel, 2004). Obviously if the human factors were to be reduced, the incidences of road accidents would significantly be reduced. And one way of reducing the road accidents is by enlightening the people, especially the young, through a formal education process.

All in all, the realities of the highway accidents simply don’t leave a sound reason for the withdrawal of traffic education from schools. If anything, it only makes the course even more vital to the young minds in the school system. Instead of doing away with it, strategies should be hatched to try and deal with the financial crisis. For example, partnerships with private traffic education companies may help ease the burden on the government. This may even actually improve the quality of the courses by making what is taught more relevant and updated. Whatever is done however, traffic safety education should remain a core course within the school systems.

Vogel, L. and Bester, C.J. 2004 A relationship between accident types and causes. Web.

Leonard Evans Traffic Safety and the Driver Science Serving Society 1991, pg 75.

Margaret Plecki N.D. Current issues in Washington State School Finance. 2009. Web.

Mathew L. Wald 2006 Licensing restrictions save young driver’s lives The New York Times. Web.

Mischelle Weedman-Davis 2008 Seattle Washington Accident Law Blog. Web.

Peter Allens N.D. Administrative guidelines for traffic safety education. 2009. Web.

WTSC (Washington Traffic Safety Commission) 2007 School Zone grants NR. Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, November 12). Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level. https://studycorgi.com/traffic-safety-education/

"Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level." StudyCorgi , 12 Nov. 2021, studycorgi.com/traffic-safety-education/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level'. 12 November.

1. StudyCorgi . "Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level." November 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/traffic-safety-education/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level." November 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/traffic-safety-education/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level." November 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/traffic-safety-education/.

This paper, “Importance of Traffic Safety Education at the School Level”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: March 26, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- Essay Topic Generator

- Summary Generator

- Thesis Maker Academic

- Sentence Rephraser

- Read My Paper

- Hypothesis Generator

- Cover Page Generator

- Text Compactor

- Essay Scrambler

- Essay Plagiarism Checker

- Hook Generator

- AI Writing Checker

- Notes Maker

- Overnight Essay Writing

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Tips

- Essay Writing (by Genre)

- Essay Writing (by Topic)

Essay on Traffic Education & Its Importantce: Keys to Success

Do you have a driving license? Are you a good driver who knows and follows all the rules?

Have you ever been involved into an accident?

These days, more and more people get their licenses and drive cars, since it is one of the most convenient and quickest ways of getting around. As the number of cars and drivers grows, the number of traffic jams and accidents also increases.

This is why it is so important to get proper traffic education or, at least, write an informative and a well-organized essay on traffic education.

It seems like your essay on traffic education causes you some difficulties. Thus, let our writers help you.

Naturally, the first thing you have to do is define the purpose of writing your essay on traffic education. Do you just want to highlight some specific points? Do you want to make a strong, persuasive essay on traffic education and call people for some actions?

No matter what type of essay on traffic education you choose, you cannot go without the following:

- Solid arguments;

- Facts and statistics;

- Experts’ opinions, etc.

Topics that you may cover in the essay on traffic education vary greatly. Let us give you a couple of examples:

- Emergency services and their roles on the accident scene;

- Types of traffic offenses;

- Driver’s legal rights and responsibilities;

- Major challenges that novice drivers face;

- Preventing traffic accidents, etc.

If you want to prepare a persuasive essay on traffic education, you may discuss something like “The importance of traffic education in schools” or “Traffic education vs. Sex education”.

Reading our articles about an essay on traffic hazards and a safety essay will be helpful for writing your essay on traffic education.

An Open Access Journal

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 March 2019

The effect of road safety education on the relationship between Driver’s errors, violations and accidents: Slovenian case study

- Darja Topolšek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1886-0688 1 ,

- Dario Babić 2 &

- Mario Fiolić 2

European Transport Research Review volume 11 , Article number: 18 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

37k Accesses

18 Citations

Metrics details

One of the pillars of road safety strategies, in almost every country in the world, is training and education. Due to the diversity and different extents of evaluation methods, the influence of educational and training programs on traffic safety is still limited. The aim of this research is to evaluate the effect of the Slovenian educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”. For this purpose 183 participants, divided into two groups: ones who participated in the program and others who did not, fulfilled the Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ) in order to identify their most common errors and violations. The results, based on the best model of multi-group moderator effect, indicate that the link between Violations and Accidents is significantly different between those who participated in the program and those who did not. This link is weaker among the respondents who participated in the program compared to others who did not. This may lead to the conclusion that the group of drivers who participated in the program has a “weaker” Violations resulting in accidents.

1 Introduction

Road accidents represent a significant social problem since 25,500 people were killed on the roads of the European Union in 2016 with more than 135,000 injured [ 10 ]. The total damage of road accidents is very difficult to estimate as it does not only include the cost of treatment and material damage, but also indirect damages in the form of: reduction of job opportunities, loss of working ability, inability to perform daily activities, direct reproductive costs of medical or professional rehabilitation, indirect reproductive police costs, court proceedings, insurance companies, etc. Depending on the Member State, it is estimated that these losses amount from 1% to even 3% of gross domestic product [ 38 ].

For this reason, road safety is one of the key focuses of the European Commission, which adopts a new European Road Safety Action Program every ten years. The main task of the Program is to reduce the number of fatalities on EU roads. Since the overall road safety depends on the interaction of three main elements: human, road and vehicle, one can conclude that traffic accidents represent a failure of the whole traffic system (interaction between the three elements). For a long time, human error was most often considered as the main and more or less fatal cause of road safety problems since humans are, by nature, subject to errors. Although humans make a lot of errors, these errors are not always the true cause of accidents. Namely, a different phenomenon related to the road itself or the vehicle may trigger the human error and thus be the true cause of an accident. This is why the modern road safety strategies clearly differentiate the factors that truly cause accidents, whether they are human, environmental, vehicular, etc. Such a differentiation may lead to more diverse and efficient solutions directed toward preventing human errors by acting on their identified causes, and by promoting a better ergonomics of the driving system in accordance with human capacities and weaknesses [ 8 ].

In addition to the mentioned differentiation, training and education are one of the pillars of road safety strategies and solutions for increasing road safety. In almost every country in the world road safety education is, to a certain extent, part of formal education system. It is also a constituent part of initiatives, programs and activities outside the formal education. However, although there are plenty of road safety education programs, the number of those that are followed by detailed evaluation is rather limited [ 7 ]. Different and/or poor evaluation methods may be the reason why several studies failed to prove the positive outcomes of these programs [ 9 , 19 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 36 ].

On the other hand, with better evaluation methods and research on drivers’ education on road safety, recent studies [ 21 , 30 ] showed statistically significant reduction in road accidents. The studies indicated that teens who underwent the education program were less likely to be involved in accidents during their first two years of driving, compared to the teens who did not go through the education. Based on the analysis of effectiveness of road safety education in Nebraska, the authors Shell et al. [ 30 ] concluded that the non-educated group was 1.22 times more likely to get in an accident than those who underwent the education program. In their analysis, authors took into account key demographic factors such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, urbanicity and household income.

A more large-scale study examined the safety performance of teen drivers who underwent the education program and those who did not [ 21 ]. The study was conducted in two stages. Firstly, a sample of teen drivers was surveyed prior to completing the educational program and their accidents and convictions were compared once they got their provisional license. In the second stage, historical records were used to examine the accidents and convictions of a much larger population of Oregon teens who had and had not completed the approved educational program [ 21 ]. The authors concluded that the safety effects of approved educational program are either neutral (based on the first part of the study) or cautiously optimistic (based on the results of the second part).

Since from the above mentioned one can conclude that there are gaps in the evaluation methods and different strategies used in the available literature, further research is needed in order to get better insight on the influence of educational programs on road safety. In order to develop efficient training and education activities, it is primarily necessary to identify common human errors and violations. A frequently used method for this is Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ), originally developed in Britain by [ 26 ].

The DBQ is based on the theoretical taxonomy of aberrant behaviours and represents a psychometric instrument and accident predictor. The main distinction between errors and violations is based on the assumption that they have different psychological origins and demand different modes of remediation. Errors are defined as “the failure of planned actions to achieve their intended consequences”, while violations are “deliberate deviations from those practices believed necessary to maintain the safe operation of a potentially hazardous system” [ 26 ].

The main purpose of this research is to evaluate the DBQ factors used to develop the best model of multi-group moderator effect among drivers who attended the Slovenian educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” compared to those who did not attend the program. The program is organized by the Institute for Innovative Safe Driving Education “ Vozim ” which was founded on the initiative of young paraplegics/victims of road accidents. Since 2008, the Institute has been implementing a preventive program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”, focused on future young drivers between the age of 15 and 22. An innovative interactive road safety program is based on personal stories of victims, injured in road traffic accidents, who through their own experience provide direct information related to the importance of safe driving and compliance with road traffic regulations. Through personal stories told by people injured in road traffic, young people get the insight into their life before the accident, the car accident and life after it. In this way, they become aware of the importance of safe and responsible driving and possible consequences if disregarding them. Young people therefore learn firsthand about the causes of traffic accidents, tips for safe driving and as well as the lives of the disabled and their “new life” after rehabilitation, thereby encouraging the destigmatization of physically handicapped individuals. Through the stimulated discussions and questions, participants actively shape the content of the lectures. In this way, participants and disabled persons have more personal contact and share more intimate details, which ultimately results in their connection on deeper level. With this, participants, get clear message that traffic accidents are real and do not happen just “to other people” but may also happen to them. Based on what they heard during program, young participants may “think twice” about what may happen before they engage in risky driving.

The main goal of this research is to evaluate how this unique approach affects driver’s errors and violations and how they are connected to the frequency of traffic accidents caused by young drivers who participated in the program and those who didn’t.

2 Conceptual framework, survey and hypotheses

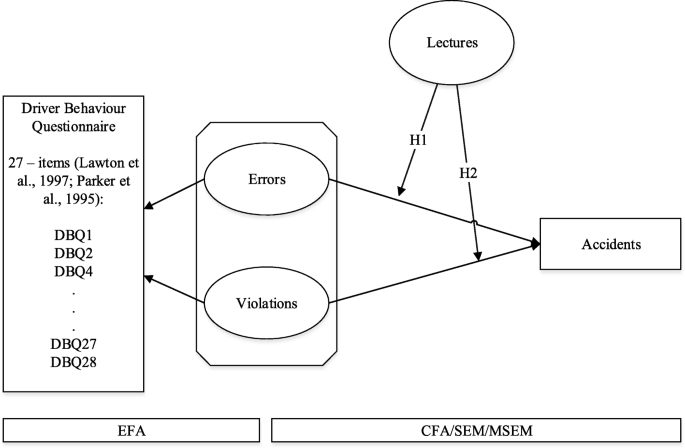

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework with the hypothesized model. The framework consists of twenty-seven (27) items of the DBQ questionnaire, which are symbolized by variables DBQi, i = 1,2,4…28 (3 is excluded based on recommendation of authors [ 16 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]). Two DBQ factors (Errors and Violations) and accidents are represented as the number of accident caused by participant.

The conceptual framework

The main aim of this framework is to evaluate the effect of Errors and Violations on the number of accidents caused by a participant. As mentioned in the introduction, the aim of this study is to evaluate the DBQ factors used to develop the best model of multi-group moderator effect among drivers who participated in the Slovenian road safety program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”, compared to those who did not attend the program. In addition, the analysis of the impact of these behaviours on the number of accidents caused by the two studied groups is conducted. Based on this research gap the following two hypotheses were explored:

H1. The road safety education program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” has a moderation effect on the relationship between Errors and Accidents ; this relationship is “weaker” for those who participated in the program than for those who did not.

H2. The road safety education program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” has a moderation effect on the relationship between Violations and Accidents ; this relationship is “weaker” for those who participated in the program than for those who did not.

The main aim of this research is therefore to determine the difference between how Violations and Errors affect the Accidents depending on whether the driver participated in the Slovenian road safety program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”, or not. The “weaker” relationship in this case means, that those who did participate road safety program may cause less accident derived from Errors/Violations than those who did not attend the program.

2.1 Instruments

The questionnaire was divided in two sections. The first part consisted of 27 driver behaviour questions that were selected from the previous versions of the DBQ [ 16 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The questionnaire was designed to evaluate the effect of certain control variables on the behavioural factors. In this case it was used to evaluate the differences between “safe” driving behaviour depending on the participation in the education program. Respondents were asked to indicate how often they commit each of the violations or errors showed in Table 1 , when driving a car on a 5-point Likert scale from “Never” to “Nearly all the time”.

The second part contained demographic questions regarding age and gender as well as information related to the driving experience, their driving habits (how often do they drive a car: daily, weekly, monthly, yearly), estimated annual distance driven and accidents in the past years.

2.2 Participants

The data was collected over four week period in 2017 by means of online surveys. The sampling strategy was intended to gather data from two different driver groups. The first group consisted of people who had participated in the road safety educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”. The second group was composed of young drivers (nearly the same age) who did not attend the education program.

In total 183 participants fully completed the questionnaire. Of that number, 54.6% were the drivers who participated in the program and 45.4% the ones who did not. The majority of the participants were female (72.1%) between 20 and 29 years old (21.1% below 20), and they all have valid driver’s licence (35% for less than 2 years and 34% from 2 to 5 years).

2.3 Data analysis

As mentioned before, the aim of the study is to evaluate the DBQ factors used to develop the best model of multi-group moderator effect among two groups of drivers and thus evaluate the efficiency of the educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”. Therefore, we used the exploratory factor analysis in order to indetify the nature of the latent factors (constructs) and to estimate their indicator items loadings [ 13 ].

Using covariance-based structural equation modelling the DBQ variables and road accidents were carried in the modelling of moderated mediation in order to investigate the relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable and the kind of the mediating variables. In order to model the moderating effect for latent construct, an alternative method was used for assessing the effect of moderator variable in the model in covariance-based structural equation modelling - Multi-group CFA. The critical ratio difference test which represents the parameter estimate divided by its standard error; as such, it operates as a z-statistic in testing that the estimate is statistically different from zero was used. For the hypothesis to be rejected the test values needs to be > ±1.96 with the probability level of 0.05.

The descriptive statistics of the measured data was investigated with the emphasis on the analysis of normality because of disturbed accuracy of model validation if the data are non-normal [ 35 ]. Normality tests are usually conducted with the skewness index (│SI│ < 3) and kurtosis index (│KI│ < 7) of the data.

3.1 Exploratory factor analysis

The responses to the 27 DBQ items were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), using the Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) algorithm, with additional Promax rotation (and Kaiser normalization). PAF was our preferred method for estimation, given that it does not rely on the assumption of multivariate normality, which can definitely be treated as an advantage [ 11 ].

Different research about the DBQ questionnaire have implicated that the subsequent factor model can be articulated by four, three or two essential factors [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 16 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 32 ].

The possibility that the factor analysis may be used without any concerns was tested by two tests: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin KMO test and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS) [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. The BTS value was significant (χ 2 = 1225.173 with df = 231 and p < 0.001), while the KMO value was 0.846 > 0.5. According to the recommendation of some authors [ 12 , 18 , 27 ], the achieved BTS and KMO values imply that the EFA can be reliably conducted in further research.

For the factors extraction process, the principal axis factoring (PAF) algorithm with the Promax rotation was used. The Scree plot and Eigen value were inspected to determine the optimal number of factors. Both of them suggested the presence of only two factors. The two factors explained the 43.75% of the variance. According to [ 13 ], only those items which are significantly loaded on corresponding factors (loadings > 0.45; communalities over 0.5) were retained in the model.

We labelled the first factor Errors because it contains items related to errors or lapses. The second factor was labelled Violations because of high loading items reflecting aggressive violation or Ordinary violations [ 4 , 16 , 20 ].

Factor loadings of two-factor structure can be seen in Table 2 .

3.2 Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed in order to test the fit of the initial derived factor model to the exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The maximum likelihood (ML) method was used to estimate all model parameters at first. While estimating the parameters, the difference between the data-based covariance matrix and the model-implied covariance matrix was minimized [ 14 ]. The goodness of fit indicates proper fit of the model because all of fit measures are higher than threshold ranges: Normed fit index (NFI = 0.913), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI = 0.986), Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.995), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.032), Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR = 0.0402) (Byrne 2009). Convergent and discriminant validity were also tested. Both the adequate composite reliability and average variance extracted were inside the interval and it can be concluded that there are no validity concerns.

3.3 Structural equation modelling results

This study applies two variables, namely Errors and Violations, derived from the DBQ and a variable named Accident, representing the number of accidents caused by a participant. Maximum likelihood estimator in structural equation modelling was used to determine the probability values ( p -value) in order to identify the research hypothesis as the prior in the empirical study.

We first tested the global model, measuring the effect of Errors and Violations on Accidents (number of traffic accident caused by driver). This model fits well to the data (χ2 = 115.306; df = 181; GFI = 0.948 NFI = 0.912; CFI = 0.987; RMSEA = 0.021; SRMR = 0.042). It was predicted that Driver who makes more Errors causes more traffic accidents, but this path has a significant and negative effect on Accidents (− 0.34, p < 0.05). As predicted, Table 3 shows that Violations have significant and positive effect on Accidents (0.294, p < 001). The full model is shown in Table 3 .

3.4 Moderating structural equation modelling results

After the measurement model has been validated, the next step was to assemble these constructs in the moderated structural equation modelling. The main problem of this research was focused on the difference between two groups of drivers. The first group consisted of drivers who participated in the road safety educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” and the second group of the ones that did not.

The moderator-mediator in the form of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to examine the interrelationship among the two mentioned groups.

In this case, the effect of Errors and Violations on Accidents upon a multi-group analysis is performed. The results indicate that the relationships in our model are different between the two groups in one case. The link between Violations and Accidents is significantly different between those who participated in the program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” and those who did not (Z = − 1.313**) as shown in Table 4 . This link is stronger among the participants who did not participate in the program (β = 0.646, p < 0.001) compared to the others who did (β = 0.252, p < 0.05). This indicates that the drivers who participated in the program obey the traffic regulations and are more responsible when driving, meaning that they may violate the regulations less and thus cause less accidents. Other relationships do not present significant differences between the groups. Based on this, it can be concluded that the hypothesis H2 is verified, while the hypothesis H1 cannot be verified.

For analyzing possible differences between male and female participants the Multiple-Group Analysis was conducted. The results show that for both paths (Errors-Accidents and Violation-Accident) groups are not different at the model level as well as at the path level. This result implies that, even though with lower male sample, gender of participants did not affect the “strength” of the relationship between Errors-Violations and Accidents, i.e. there are no statistically significant differences between male and female participants.

4 Discussion

Educational programs represent one of the core road safety measures in most of the countries around the world. However, the efficiency of these programs and their positive effect on overall road safety is still unknown to a certain extent. One of the main reasons for this is the diversity of used strategies and evaluation methods. Nevertheless, recent studies [ 21 , 30 ] show that with improved educational approaches and evaluation methods, relatively small but still statistically significant reduction in road accidents, involving drivers who attended the programs, is possible.

Based on the mentioned gaps and positive findings in the available literature, the main purpose of this research was to evaluate the efficiency of the Slovenian educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk”. The program is based on the personal contact between participants (young drivers) and disabled persons. In this way, young drivers, who do not have enough experience, firsthand hear and see what may happen with the risky driving. The aim of this paper was to evaluate how this unique approach affects driver’s errors and violations and their connection to the frequency of traffic accidents caused by young drivers who participated in the program and those who didn’t.

In order to identify common human errors and violations, the Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ) was used to examine the moderation effect of a variable, namely the participation in the program (categorical variable), in the relationship path between exogenous and endogenous constructs. This approach also allowed us to assess how well our conceptual model as a whole fits the data.

The test of a full model (regardless of whether they did/did not participate in the program) measuring effect of Errors and Violations on Accidents showed that the relationship between driver’s Errors and number of Accidents is significantly negative. This means that the drivers who make more errors do not cause more accidents. On the other hand, the drivers who make more Violations are more susceptible to cause traffic Accidents.

The moderator-mediator in the form of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used in order to examine the interrelationship between the two analysed groups (drivers who participated in the program and those who did not). The results of the effect of Errors and Violations on Accidents based on the multi-group analysis show that the link between Violations and Accidents is “weaker” among the participants who participated in the program, compared to those who did not. This indicates that the drivers in the first group became more aware and responsible after the program. In other words, the participants who attended the Slovenian road safety program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” may violate traffic regulations less and thus cause less accidents compared to those who did not participated in the program. In addition, difference of gender was not found meaning that the relationship between Errors-Violations and Accidents is the same for male and females.

The limitation of this study is mainly related to the fact that data collection was conducted in a relatively short period after the educational program took place. In the future, after each education period the driving behavior of the participants who attended the education should be investigated in order to get bigger dataset and stronger proof of here presented results. Also, the driving behavior of the participants investigated in this study should be periodically checked in longer time period, i. e. with the increase of their experience. In that way the long-term effect of the program may be determined since it is known that driving experience is negatively correlated to the risk of accidents and injuries [ 1 , 37 ].

The relationship between driver’s Errors, Violations and the number of Accidents should be analysed in a longer period of time in order to get a deeper insight on the effect of educational programs on the drivers’ behaviour.

5 Conclusion

A Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ) was used to determine most common errors and violations and to develop model of multi-group moderator effect among drivers who attended the Slovenian educational program “I still drive, but I cannot walk” compared to those who did not attend the program. Results of a multi-group analysis showed indicated that the relationships between Violations and Accidents are different between the two groups (drivers who participated in the program and those who did not), indicating that the drivers who participated in the program may cause less Violations resulting in accidents. Results also indicate that the relationships between Errors and Accidents do not present significant differences between the groups. From all the above, it may be concluded that the program had a positive effect on the behaviour of young people who participated in it, meaning that they may ultimately be more responsible drivers and thus cause less accidents. These results show that more personal contact based on the empathy, emotions and mutual understanding may be more efficient in increasing awareness of the young drivers. Ultimately, this study represents a positive methodology for evaluation of a road safety educational program and as such provides significant scientific contribution.

Ballesteros, M. F., & Dischinger, P. C. (2002). Characteristics of traffic crashes in Maryland (1996 1998): Differences among the youngest drivers. Accid Anal Prev, 34 (3), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00023-9 .

Article Google Scholar

Bener, A., et al. (2013). A cross “ethnical” comparison of the driver behaviour questionnaire (DBQ) in an economically fast developing country. Global J Health Sci, 5 (4), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p165 .

Conner, M., & Lai, F. (2005). Evaluation of the effectiveness of the National Driver Improvement Scheme. Road safety research report, no. 64 . London: Department for Transport.

Google Scholar

Cordazzo, S. T. D., Scialfa, C. T., & Ross, R. J. (2016). Modernization of the driver behaviour questionnaire. Accid Anal Prev, 87 , 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.11.016 .

De Winter, J. C. F., & Dodou, D. (2010). The driver behaviour questionnaire as a predictor of accidents: A Metaanalysis. J Saf Res, 41 (6), 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2010.10.007 .

De Winter, J. C. F., Dodou, D., & Stanton, N. A. (2015). A quarter of a century of the DBQ: Some supplementary notes on its validity with regard to accidents. Ergonomics, 58 (10), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2015.1030460 .

Dragutinovic, N., & Twisk, D. (2006). The effectiveness of road safety education . Netherlands: Institute for Road Safety Research.

Elslande, P., Naing, C., & Engel, R. (2008). Analyzing human factors in road accidents. TRACE WP5 Summary Report Available at: http://www.transport-research.info/sites/default/files/project/documents/20130620_104810_50767_tracewp5d55v2.pdf .

Engstrom, I. et al. 2003.Young Novice Drivers, Driver Education and Training; Literature Review, VTI-Rapport 491A; Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute: Linköping, Sweden.

European Commision. 2017. Road Safety Statistics. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-675_en.htm . (04/05/2017).

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods, 4 (3), 272–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272 .

Frohlich, M. T., & Westbrook, R. (2001). Arcs of integration: An international study of supply chain strategies. J Oper Manag, 19 (2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(00)00055-3 .

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (p. 816). Prentice Hall.

Hoyle, R. H. (2012). Handbook of structural equation modeling (p. 740). The Guilford Press.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2th ed.p. 425). The Guilford Press.

Lajunen, T., Parker, D., & Summala, S. (2004). The Manchester driver behaviour questionnaire: A cross-cultural study. Accid Anal Prev, 36 (2), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00152-5 .

Lawton, R., et al. (1997). Predicting road traffic accidents: The role of social deviance and violations. Br J Psychol, 88 (2), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1997.tb02633.x .

Li, J., et al. (2013). Chinese version of the nursing Students' perception of instructor caring (C-NSPIC): Assessment of reliability and validity. Nurse Educ Today, 33 (12), 1482–1489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.05.017 .

Lonero, L., Mayhew, D.R. 2010. Large-Scale Evaluation of Driver Education Review of the Literature on Driver Education Evaluation: 2010 Update. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety: Washington, DC, USA.

Martinussen, L. M., et al. (2013). Age, gender, mileage and the DBQ: The validity of the driver behavior questionnaire in different driver groups. Accid Anal Prev, 52 , 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.12.036 .

Mayhew, D., et al. (2017). Evaluation of beginner driver education in Oregon. Safety 3 , (1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety3010009 .

Newnam, S., & Von Schuckmann, C. (2012). Identifying an appropriate driving behaviour scale for the occupational driving context: The DBQ vs. the ODBQ. Saf Sci, 50 (5), 1268–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.12.009 .

Nordfjærn, T., & Şimşekoğlu, O. (2014). Empathy, conformity, and cultural factors related to aberrant driving behaviour in a sample of urban Turkish drivers. Saf Sci, 68 , 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.02.020 .

Özkan, T., et al. (2006). Cross-cultural differences in driving Behaviours: A comparison of six countries. Transport Res F: Traffic Psychol Behav, 9 (3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2006.01.002 .

Parker, D., Reason, J. T., Manstead, A. S. R., & Stradling, S. G. (1995). Driving errors, driving violations and accident involvement. Ergonomics, 38 (5), 1036–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139508925170 .

Reason, J., et al. (1990). Errors and violations on the roads: A real distinction? Ergonomics, 33 (10–11), 1315–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139008925335 .

Sahin, M., et al. (2013). A structural equations model for assessing the economic performance of high-tech entrepreneurs. In R. Capello & T. P. Dentinho (Eds.), Globalization trends and regional development (p. 48).

Salmon, P. M., et al. (2010). Managing error on the open road: The contribution of human error models and methods. Saf Sci, 48 (10), 1225–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2010.04.004 .

Senserrick, T. M., & Swinburne, G. C. (2001). Evaluation of an insight driver-training program for young drivers. Report no. 186 . Victoria: Monash University Accident Research Centre.

Shell, D. F., et al. (2015). Driver education and teen crashes and traffic violations in the first two years of driving in a graduated licensing system. Accid Anal Prev, 82 , 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.05.011 .

Simpson, H. M. (2003). The evolution and effectiveness of graduated licensing. J Saf Res, 34 (1), 25–34.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Sümer, N., Ayvaşik, B., Er, N., Özkan, T. 2001. Role of Monotonous Attention in Traffic Violations, Errors, and Accidents. In Proceedings of the First International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training and Vehicle Design, p. 167–173. Aspen.

Thomas, F.D., III, Blomberg, R.D., Donald, L., Fisher, D.L. 2012. A Fresh Look at Driver Education in America. Report No. DOT HS 811 543. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA.

Vernick, J. D., et al. (1999). Effects of high school driver education on motor vehicle crashes, violations, and licensure. Am J Prev Med, 16 (1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00115-9 .

Weston, R., & Gore, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Couns Psychol, 34 (5), 719–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345 .

Williams, A., Preusser, D., & Ledingham, K. (2009). Feasibility study on evaluating driver education curriculum. In National Highway Safety Administration . Washington, DC: USA.

Wong, T. W., Phoon, W. O., Lee, J., Yio, I. P., Fung, K. P., & Smith, G. (1990). Motorcyclist traffic accidents and risk factors: A Singapore study. Asia Pac J Public Health, 4 (1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/101053959000400106 .

World Health Organization. 2017. Road Traffic Injuries. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs358/en /. (27/12/2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

There was no funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of some personal data included in database but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Technical Logistics, Faculty of Logistics, University of Maribor, Celje, Slovenia

Darja Topolšek

Department of Traffic Signalling, Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Dario Babić & Mario Fiolić

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DT prepared: the idea and research gap, a survey (prepared a survey, cooperated with the Institute for Innovative Safe Driving Education “Vozim”), the SEM model, and the results. DB prepared: summary, literature review, discussion and conclusion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Darja Topolšek .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Topolšek, D., Babić, D. & Fiolić, M. The effect of road safety education on the relationship between Driver’s errors, violations and accidents: Slovenian case study. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 11 , 18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-019-0351-y

Download citation

Received : 24 August 2018

Accepted : 30 January 2019

Published : 12 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-019-0351-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Driver’s education

- Traffic safety

Traffic education

By traffic education we mean all educational activities aimed at positively influencing road user behaviour, with the exception of more general public communication campaigns (see SWOV fact sheet Public communication ). The activities are mainly aimed at increasing knowledge, insight, skills and motivation. In principle, traffic education is relevant to all road users, young and old, in all road user roles: lifelong traffic education. However, little is known about the effect of traffic education on crash involvement. It is also virtually impossible to study properly. Effects on (observed) road user behaviour and knowledge, if they have been studied at all, appear to be very limited at best. Good - effective - education in any case requires logical connections between the road safety problem, the current and intended behaviour and the didactic method. Formulating educational goals (general goals, main goals and learning goals) is of great importance for educational activities and evaluating their effectiveness.

In the Netherlands, traffic lessons are a compulsory component of the primary school curriculum. In secondary education, traffic is not a compulsory subject, but (a small) part of two of the 58 educational core goals for the lower grades. The attainment targets for upper secondary education do not include road user behaviour. Traffic education for (young) adults mainly consists of theoretical and practical driver training for the various means of transport ((light) moped, car, motorcycle). Driver training falls outside the scope of this fact sheet; see SWOV fact sheet Driver Training and driving tests . In addition, there are various, voluntary courses (practical and online) for specific target groups. These often include training and information aimed at young adults and senior citizens, as well as more general skills training.

Following the example of the European LEARN! project [1] , we understand traffic education to mean all educational activities that aim to positively influence road user behaviour. These activities mainly focus on:

- Gaining knowledge and understanding of traffic rules and situations;

- Developing and improving skills through training and experience;

- Strengthening and/or changing attitudes and intrinsic motivations towards risk awareness, personal safety and the safety of other road users;

- Providing the tools necessary for a well-informed choice of transport mode.

Here we can distinguish between formal and informal education. By formal traffic education, we mean the education provided in the form of a curriculum or project, usually by a school or training institute. Informal education concerns everyday activities of parents/caregivers to impart knowledge and teach children skills to participate in traffic safely.

Public communication also aims to bring about a change in knowledge, attitude or behaviour (see SWOV fact sheet Public communication ). The main difference with traffic education as intended here is the (physical or virtual) interaction with a teacher/instructor, in groups or individually. This interaction is absent, or at least less prominent, in public communication.

Traffic education is relevant to everyone at every life stage. It is relevant to all road users who, in every possible road user role, do not have (sufficient) knowledge, insight, skills and motivation to participate in traffic safely and who are capable of learning. Thus, it is not only meant for children, but also for novice (light) moped riders, novice drivers, older drivers, novice pedelec riders, novice mobility scooterists and so on. This is called lifelong traffic education.

Lifelong traffic education stands for the idea of providing traffic education for every age group and every mode of transport. The goal is to create the conditions for safe road user behaviour in terms of knowledge, ability and willingness. These elements lead to a formal definition of lifelong traffic education: a coherent package (in terms of both age-related development and road users’ mode of transport) of consecutive and continuous activities aimed at internalising change or continuing the desired safe road user behaviour, by creating the necessary conditions for the desired behaviour (of knowledge, ability and willingness) ” [2] . There are six age-based target groups within lifelong traffic education:

- age 0 – 4 (early and preschool education)

- age 4 – 12 (primary education)

- age 12 – 16 (secondary education)

- age 16 – ca. 25 (novice drivers)

- age ca. 25 – ca. 60 (driving licence owners)

- age 60 and over (older road users)

The aim of traffic education is to achieve safe road user behaviour and the conditions required for it. These conditions concern knowledge, ability and willingness. The elaboration in educational goals should of course be tailored to the target group and their main road user role.

Defining educational goals is of great importance for defining educational activities and evaluating their effectiveness. There are general goals, main goals and learning goals (see [3] ). General goals are very broadly defined to outline the domain of learning. The general goal of traffic education is to achieve safe road user behaviour for the main road user roles of the target group and the necessary conditions in terms of knowledge, ability and willingness. Table 1 provides an example

Table 1. Examples of general goal/domain for formal traffic education by target group. Source: [3] .

Main goals subsequently describe what an education activity is meant to achieve, for example, that a child is able to cross the road safely, that a driver recognises the risk of speeding, or that someone has mastered manoeuvring a mobility scooter. Finally, learning goals are very concrete elaborations of the main goals: what does safe crossing look like, what exactly must someone who recognises the risk of speeding do or say, what manoeuvres with a mobility scooter must be mastered in what circumstances. Learning goals should always be ‘SMART’ [3] :

- S pecific (addressing a concrete subject);

- M easurable (verifiable whether the goal was met);

- A cceptable (sufficiently motivating to want to learn about the particular subject);

- R ealistic (feasible); and

- Time-bound (with a deadline).

Following the GDE matrix (Goals of Driver Education), the goals of traffic education can be organised accordingly, making a distinction by level of traffic participation and aspects of the traffic task [4] [5] . The four levels of traffic participation, the rows of the GDE matrix, are:

- General level: personal motives and tendencies (e.g., degree of impulsivity, risk acceptance).

- Strategic level: considerations and decisions prior to travel (e.g., what route to take, what time to leave).

- Tactical level: interaction in traffic (e.g. whether to give right of way, whether to indicate direction).

- Operational level: vehicle control/operation (for example, shifting gears in a car and getting on and off a bicycle).

The three aspects of the traffic task, the columns of the GDE matrix, are:

- Knowledge and skills: what you need to know and be able to do in order to participate in traffic safely.

- Risk-increasing factors: the factors that increase crash risk, why this is so and how to avoid such risks.

- Self-assessment: the extent to which you are able to participate in traffic safely and how to adjust your behavioural choices accordingly (calibration).

The role of the school

School is a logical place to provide traffic education because it offers the opportunity to provide traffic education to all children and to ensure that all children are imparted with the same knowledge, and taught the same skills, attitudes, norms and values, regardless of parents' considerations and (socioeconomic) opportunities [1] .

In the Netherlands, traffic is a compulsory part of the primary school curriculum. Together with geography, history, biology, citizenship and political studies, they are part of the subject World orientation/self-orientation . How often and how much time should be spent on the subject of traffic is not fixed. This is left to the discretion of schools [6] .

In secondary education , traffic is not a compulsory subject, but (a small) part of two of the 58 educational core goals for lower secondary education [7] :

- In the Human and Nature domain, core goal 35 is: "pupils learn about health and learn to take care of themselves, others and their environment, and how to positively influence their own and others’ safety in various living conditions (residing, learning, working, going out, traffic)."

- In the Human and Society domain, core goal 45 is: "Pupils learn - by experience and in their own environment - to recognise the effects of choices in the areas of work and health, living and recreation, consuming and budgeting, traffic and environment."

Traffic/traffic participation is not included in the so-called attainment targets for upper secondary education.

There are several teaching programmes available for primary and lower secondary education. The Toolkit LifelongTraffic education [8] offers a compact overview of Dutch programmes. Through various filters teachers may search specifically by age group, school type, subject etcetera. The programmes are developed and offered by various agencies, including ANWB, TeamAlert, VeiligheidNL and VVN.

The role of parents/caregivers

Parents also have a role in imparting knowledge and teaching their children road safety skills. This usually does not happen in the form of a programme or project as done at school, but in a more informal way, in everyday life. For example, parents can point out possible hazards to their children during the route from home to school or while driving draw their attention to certain situations or behaviour [9] . Parents/caregivers can also act as models for their children by leading by example. Informal education begins with children who do not yet go to school independently. But also, when children do go to school independently, parents can still have a positive influence on the risk behaviour of their children. Good communication is especially important with somewhat older children (adolescents) [10] .

The role of parents/caregivers in 'accompanied driving for novice drivers (in the Netherlands called 2todrive) is also a form of informal traffic education. A parent or other person travels with the novice driver for a certain period of time, so that the novice driver gains driving experience in a relatively protected environment. For more information, see SWOV fact sheet Driver training and driving tests .

Traffic education for (young) adults takes place largely in the form of theoretical and practical driver training for the various means of transport ((light) moped, car, motorcycle – see SWOV fact sheet Driver training and driving tests ). Commercial transport requires a specific driving license (C or D) and specific driver training and refresher training, such as the taxi driver training and Code 95 for truck and bus drivers.

There are also several courses (practical and online) for specific target groups. They mainly concern training and information targeting young adults on the one hand and seniors on the other. These types of activities are always voluntary, with the exception of the educational measures for offenders (see the question What is the effect of the educational measures EMG and (L)EMA? ).

Team Alert targets secondary school pupils and young adults and has also developed several educational projects. These are offered in schools and have themes such as cyclist traffic risks [11] , drink driving [12] and hazard perception [13] .

The Dutch road safety organisation VVN offers various (refresher) courses for seniors [14] , ], for example to promote road safety knowledge, courses for motorists, for (pedelec) cyclists and for mobility scooter riders (see the question What is the effect of refresher courses for seniors? ). The Doortrappen (keep pedalling) programme of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management also targets seniors, with the aim of enabling them to cycle as long and as safely as possible (see the question What is What is the effect of 'Doortrappen'? ). The Fietsersbond (Dutch Cyclists’ Union) has its own cycling school which offers courses to children and seniors, and also to new Dutch citizens such as migrants, asylum seekers and expats [15] .

Good, i.e. effective, education requires logical cohesion between the road safety problem, current and intended behaviour and the didactic method. Fishers and colleagues [16] distinguish 10 steps or topics that are relevant in assessing the quality of a traffic education programme:

- Problem behaviour: is the issue relevant?

- Target group: is the target group unambiguously defined?

- Learning goals: are the learning goals sufficiently concrete?

- Working methods: are the working methods suited to the target group and the learning goals?

- Design: is the content correct and the design appropriate?

- Intermediate progress: is intermediate learning progress measured?

- Manual: is there a manual and is it clear?

- Implementation: are the practical aspects of implementation well described?

- Process evaluation: is an inventory of users' experiences provided?

- Effect measurement: have the effects of the programme been measured (appropriately)?

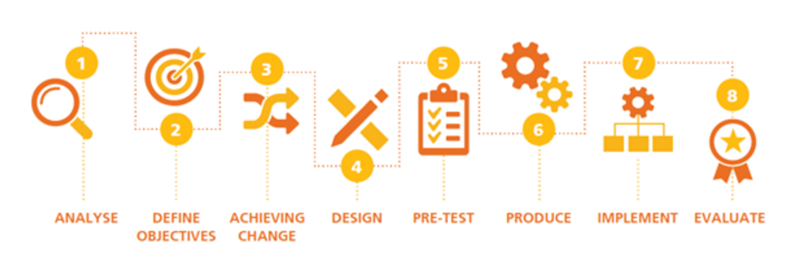

These steps largely correspond to the handbook of the European project LEARN! for developing and implementing traffic education programmes [17] :

Furthermore, it is important that a programme has clear, concrete main goals and learning goals, that the lesson content matches these one-to-one, and that the didactic methods fit the way children of a certain age learn [3] - see the question What are goals of traffic education? and What didactic principles and working methods are there? . Twisk [18] for example concludes that there is a need for programmes that allow young people to practice in complex traffic situations, but in which additional hazards are reduced as much as possible. In the practice of the school system, however, this is not easy to achieve. Possibly, simulated conditions, for example using simulators or virtual reality could offer a more practical alternative (see the question What didactic principles and teaching formats are there? ).

Didactic principles

The following general didactic principles also apply to traffic education [3] :

- The motivation principle: learning is faster and more thoroughly when pupils are intrinsically motivated to learn.

- The integration principle: the material taught must be consistent with the pupil’s existing knowledge. What has been learned must also be applicable in other situations (transfer).

- The visualisation principle: lessons should make maximum use of sensory perception.

- The activation principle: it is important to have pupils actively participate in lessons.

- The repetition principle: repeating the subject matter ensures consolidation, repetition in different contexts is beneficial, as is spaced repetition.

- The differentiation principle: it is important to pay attention to the differences between pupils in interest, learning pace and intellectual base.

Teaching formats

Teaching formats are ways of delivering subject matter to pupils. So, it is not about what is taught, but about how it is taught. Which format is best, depends on what and who you want to teach or train. In traffic education, there is a distinction between, for example [3] theoretical and practical teaching formats, and between group training and individual training.

Theory versus practice Knowledge about traffic rules can, in principle, be transferred in class. For the actual application of these rules and for learning safe behavioural strategies, practising in real traffic is indispensable for young children, at least in the first years of primary education. They cannot yet translate theoretical knowledge about rules or desired behaviour into actual behaviour in real traffic. As children get older, this becomes easier. Practising remains important, however, but it can increasingly be done in a simulated traffic situation, for example in the schoolyard, or with scale models or virtual reality.

Group training versus individual training In group education, the subject matter is offered to a group of learners at the same time. This is the case, for example, in schools and adult courses. The size of the group varies greatly. The advantage of group education, besides efficiency, is that the students can learn from each other, for example in discussions or when doing assignments together. Individual education involves a one-to-one relationship between student and teacher. This is usually done for practising very specific skills where mistakes during the learning process can have serious consequences. In such cases it is crucial that the teacher can intervene in time. The best-known example of individual traffic education is practical driver training.

Use of teaching material and (new) media

Traditionally, traffic education uses illustrations with photos and videos, sometimes scale models or traffic situations recreated in the schoolyard. New technologies make it possible to adopt a more interactive and realistic approach on an individual level, for example using virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) techniques. Several studies have shown that children behave more safely after training with VR or AR, or at least when this is also measured with AR or VR [19] [20] [21] . To what extent VR and AR methods also have behavioural effects in real traffic has not/barely been studied [22] . The same is more or less true for serious gaming on a tablet or via VR/AR [23] [24] [25] .

Especially for (young) adults, there are also e-learning or online courses (distance learning via Internet or applications) in the field of road safety. Effects of such courses have rarely been studied, but evaluation of an online hazard perception training for novice drivers shows that positive effects are possible [26] .

Not much, and certainly not much methodologically sound, research has been done on the effects of traffic education. So, we do not know the effect of most traffic education programmes. The research that has been done concerns, for the most part, primary and secondary school programmes. This allows us to conclude that some traffic education projects can lead to (small) changes in behaviour and increased knowledge. In a few cases, however, traffic education can also lead to an undesired effect. For most traffic education programmes, the effect on crash involvement is unknown. Two types of traffic education for which a positive effect on crash risk was found are a general resilience training (see the question What is the effect of general resilience training? ) and hazard perception training (see the question How useful is hazard perception as part of driver training and driving tests? In the SWOV fact sheet Driver training and driving tests ).

Many educational programmes are not evaluated or are only evaluated at the process level. Studies that do look at effects are often too small in scale to draw conclusions. Also, many of the evaluation studies are methodologically inadequate. An older but large-scale meta-analysis [27] reviewed 674 evaluation studies, of which only 15 were found to meet methodological requirements. Often a proper control group was missing and allocation to the experimental group or the control group was not blind and random. However, proper evaluation of (traffic) education programmes is very important as it forms the (empirical) basis for further improvement (see the question How can traffic education be further improved? ). In addition, proper evaluation is important since traffic education programmes differ from one another enormously. If a programme works for a specific target group, specific learning goals and a certain teaching method, this does not automatically imply that it will work equally well for another target group, other learning goals and another teaching method.

The effect of traffic education is almost never measured in terms of crashes or crash risk. This is also virtually impossible because crashes are ultimately very rare events. Effects of traffic education are generally measured in terms of behaviour, sometimes observed behaviour, often self-reported behaviour. In addition, knowledge and attitudes are also considered. It is not known to what extent these effect measurements are good predictors of crash risk.

The aforementioned meta-analysis [27] concluded that some programmes teaching children how to cross the road safely may improve behaviour. They may also improve knowledge, but all in all the authors concluded that (pg. 4): " There is no reliable evidence supporting the effectiveness of pedestrian education for preventing injuries in children and inconsistent evidence that it might improve their behaviour, attitudes, and knowledge ."

The results of a later Dutch study reviewing a total of eleven different education programmes for primary and secondary schools [28] [29] , confirm this general conclusion. They showed that some reviewed projects had, at most, a small effect on self-reported behaviour, but could not determine whether this was associated with actually safer behaviour or crashes.

However, traffic education is also not a matter of ‘doesn't help, doesn't hurt’; projects that are not properly designed may also have an adverse effect [30] [31] .

The lack of unequivocal evidence for the effectiveness of traffic education does not mean that it should be abolished. Even if traffic education apparently does not immediately lead or hardly leads to safer behaviour, everyone will at least need to know the most important traffic rules and have some basic skills in order to participate in traffic safely.

Little (proper) research has been done on the effects of primary school traffic education. The research that has been done concludes that some traffic education projects can lead to (small) changes in behaviour and increased knowledge. The effect on crash involvement is unknown. For more information, see the question What is the road safety effect of traffic education? .

The road safety effect of the primary school traffic test, organised by the Dutch road safety organisation VVN, is unknown.

The VVN traffic test is the conclusion of a continuous road safety curriculum in primary education [32] and tests the learning goals defined for group 7 and 8. It consists of a theory test and a practical cycling test for pupils in group 7 or 8 of primary school. The theory test consists of 25 multiple-choice questions about situations in their roles as pedestrians, cyclists and passengers. For the practical test, pupils cycle a pre-set route and volunteers assess whether the pupils are demonstrating safe conduct using a checklist. For more information, see examen.vvn.nl.

The road safety effect of the aforementioned road safety curriculum with the concluding traffic test has not been studied. However, the Dutch educational assessment organisation Cito does analyse the validity of the theory questions every year and an external agency investigates (bi)annually) what pupils think about the VVN traffic test and the practice tools and how they could be improved [8] .

There is no information on the effectiveness of mobility scooter courses and training.

There are various courses for mobility scooter users, including those provided by mobility scooter suppliers, occupational therapists and safety organisations (especially VVN). For more information, see SWOV fact sheet Mobility scooters, enclosed disability vehicles and microcars . However, to our knowledge, the effectiveness of the courses has never been assessed.

In the Netherlands, there are several road safety refresher courses for seniors; often organised by VVN, sometimes in cooperation with provinces or municipalities. Other parties also offer refresher courses, such as the ANWB and the Fietsersbond, as well as commercial parties, such as driving schools. As far as we know, the road safety effect of Dutch refresher courses has not been studied. International research shows that training that is well tailored to the individual driver can have a positive effect on the knowledge and driving behaviour of older drivers [33] .