10 easy ways to fail a Ph.D.

The attrition rate in Ph.D. school is high.

Anywhere from a third to half will fail.

In fact, there's a disturbing consistency to grad school failure.

I'm supervising a lot of new grad students this semester, so for their sake, I'm cataloging the common reasons for failure.

Read on for the top ten reasons students fail out of Ph.D. school.

Focus on grades or coursework

No one cares about grades in grad school.

There's a simple formula for the optimal GPA in grad school:

Anything higher implies time that could have been spent on research was wasted on classes. Advisors might even raise an eyebrow at a 4.0

During the first two years, students need to find an advisor, pick a research area, read a lot of papers and try small, exploratory research projects. Spending too much time on coursework distracts from these objectives.

Learn too much

Some students go to Ph.D. school because they want to learn.

Let there be no mistake: Ph.D. school involves a lot of learning.

But, it requires focused learning directed toward an eventual thesis.

Taking (or sitting in on) non-required classes outside one's focus is almost always a waste of time, and it's always unnecessary.

By the end of the third year, a typical Ph.D. student needs to have read about 50 to 150 papers to defend the novelty of a proposed thesis.

Of course, some students go too far with the related work search, reading so much about their intended area of research that they never start that research.

Advisors will lose patience with "eternal" students that aren't focused on the goal--making a small but significant contribution to human knowledge.

In the interest of personal disclosure, I suffered from the "want to learn everything" bug when I got to Ph.D. school.

I took classes all over campus for my first two years: Arabic, linguistics, economics, physics, math and even philosophy. In computer science, I took lots of classes in areas that had nothing to do with my research.

The price of all this "enlightenment" was an extra year on my Ph.D.

I only got away with this detour because while I was doing all that, I was a TA, which meant I wasn't wasting my advisor's grant funding.

Expect perfection

Perfectionism is a tragic affliction in academia, since it tends to hit the brightest the hardest.

Perfection cannot be attained. It is approached in the limit.

Students that polish a research paper well past the point of diminishing returns, expecting to hit perfection, will never stop polishing.

Students that can't begin to write until they have the perfect structure of the paper mapped out will never get started.

For students with problems starting on a paper or dissertation, my advice is that writing a paper should be an iterative process: start with an outline and some rough notes; take a pass over the paper and improve it a little; rinse; repeat. When the paper changes little with each pass, it's at diminishing returns. One or two more passes over the paper are all it needs at that point.

"Good enough" is better than "perfect."

Procrastinate

Chronic perfectionists also tend to be procrastinators.

So do eternal students with a drive to learn instead of research.

Ph.D. school seems to be a magnet for every kind of procrastinator.

Unfortunately, it is also a sieve that weeds out the unproductive.

Procrastinators should check out my tips for boosting productivity .

Go rogue too soon/too late

The advisor-advisee dynamic needs to shift over the course of a degree.

Early on, the advisor should be hands on, doling out specific topics and helping to craft early papers.

Toward the end, the student should know more than the advisor about her topic. Once the inversion happens, she needs to "go rogue" and start choosing the topics to investigate and initiating the paper write-ups. She needs to do so even if her advisor is insisting she do something else.

The trick is getting the timing right.

Going rogue before the student knows how to choose good topics and write well will end in wasted paper submissions and a grumpy advisor.

On the other hand, continuing to act only when ordered to act past a certain point will strain an advisor that expects to start seeing a "return" on an investment of time and hard-won grant money.

Advisors expect near-terminal Ph.D. students to be proto-professors with intimate knowledge of the challenges in their field. They should be capable of selecting and attacking research problems of appropriate size and scope.

Treat Ph.D. school like school or work

Ph.D. school is neither school nor work.

Ph.D. school is a monastic experience. And, a jealous hobby.

Solving problems and writing up papers well enough to pass peer review demands contemplative labor on days, nights and weekends.

Reading through all of the related work takes biblical levels of devotion.

Ph.D. school even comes with built-in vows of poverty and obedience.

The end brings an ecclesiastical robe and a clerical hood.

Students that treat Ph.D. school like a 9-5 endeavor are the ones that take 7+ years to finish, or end up ABD.

Ignore the committee

Some Ph.D. students forget that a committee has to sign off on their Ph.D.

It's important for students to maintain contact with committee members in the latter years of a Ph.D. They need to know what a student is doing.

It's also easy to forget advice from a committee member since they're not an everyday presence like an advisor.

Committee members, however, rarely forget the advice they give.

It doesn't usually happen, but I've seen a shouting match between a committee member and a defender where they disagreed over the metrics used for evaluation of an experiment. This committee member warned the student at his proposal about his choice of metrics.

He ignored that warning.

He was lucky: it added only one more semester to his Ph.D.

Another student I knew in grad school was told not to defend, based on the draft of his dissertation. He overruled his committee's advice, and failed his defense. He was told to scrap his entire dissertaton and start over. It took him over ten years to finish his Ph.D.

Aim too low

Some students look at the weakest student to get a Ph.D. in their department and aim for that.

This attitude guarantees that no professorship will be waiting for them.

And, it all but promises failure.

The weakest Ph.D. to escape was probably repeatedly unlucky with research topics, and had to settle for a contingency plan.

Aiming low leaves no room for uncertainty.

And, research is always uncertain.

Aim too high

A Ph.D. seems like a major undertaking from the perspective of the student.

But, it is not the final undertaking. It's the start of a scientific career.

A Ph.D. does not have to cure cancer or enable cold fusion.

At best a handful of chemists remember what Einstein's Ph.D. was in.

Einstein's Ph.D. dissertation was a principled calculation meant to estimate Avogadro's number. He got it wrong. By a factor of 3.

He still got a Ph.D.

A Ph.D. is a small but significant contribution to human knowledge.

Impact is something students should aim for over a lifetime of research.

Making a big impact with a Ph.D. is about as likely as hitting a bullseye the very first time you've fired a gun.

Once you know how to shoot, you can keep shooting until you hit it.

Plus, with a Ph.D., you get a lifetime supply of ammo.

Some advisors can give you a list of potential research topics. If they can, pick the topic that's easiest to do but which still retains your interest.

It does not matter at all what you get your Ph.D. in.

All that matters is that you get one.

It's the training that counts--not the topic.

Miss the real milestones

Most schools require coursework, qualifiers, thesis proposal, thesis defense and dissertation. These are the requirements on paper.

In practice, the real milestones are three good publications connected by a (perhaps loosely) unified theme.

Coursework and qualifiers are meant to undo admissions mistakes. A student that has published by the time she takes her qualifiers is not a mistake.

Once a student has two good publications, if she convinces her committee that she can extrapolate a third, she has a thesis proposal.

Once a student has three publications, she has defended, with reasonable confidence, that she can repeatedly conduct research of sufficient quality to meet the standards of peer review. If she draws a unifying theme, she has a thesis, and if she staples her publications together, she has a dissertation.

I fantasize about buying an industrial-grade stapler capable of punching through three journal papers and calling it The Dissertator .

Of course, three publications is nowhere near enough to get a professorship--even at a crappy school. But, it's about enough to get a Ph.D.

Related posts

- Recommended reading for grad students .

- The illustrated guide to a Ph.D.

- How to get into grad school .

- Advice for thesis proposals .

- Productivity tips for academics .

- Academic job hunt advice .

- Successful Ph.D. students: Perseverance, tenacity and cogency .

- The CRAPL: An open source license for academics .

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

Academic Challenges: How to Overcome PhD Problems and Academic Failure

Completing a PhD can be difficult . No matter how much planning you do, there will almost certainly be times when academic challenges mean that things don’t go the way you’d like them to.

Today I want to illustrate some of the academic failures I experienced with my own PhD. I hope that sharing these PhD problems and what I learned may help you. Or if nothing else reassure you that you’re not alone!

This list certainly isn’t complete, but I want to give a flavour of wide-ranging failures, starting from PhD applications through to the completion of my project.

A reader suggested the topic of academic challenges. If you have a suggestion for something you’d like covered please leave a comment or send me a message .

Academic Challenges During My PhD Applications

1) taking three years of applications to get a funded phd position.

Academic failure: I applied for my first PhD position the year after I finished my undergraduate degree. But I didn’t actually start a PhD until three years’ worth of applications later.

I made the mistake of not casting a wide enough net and failed to consider how important funding is. I naively thought that as soon as I got offered a place I was sorted. Little did I realise that funding can be the main hurdle.

Over these three years I applied to only five projects in total:

| 2013 | Imperial | Project-specific PhD | Accepted, no funding |

| 2014 | Imperial | Project-specific PhD | Accepted, not ideal |

| 2016 | Imperial | Project-specific PhD | Accepted, won a scholarship |

| 2016 | Leeds | Accepted with a stipend | |

| 2016 | Oxford | Rejected at interview, see details in the next section below! |

Key learnings

Although I got offered a place for the first PhD I applied for back in 2013, I didn’t secure any funding. Now I know that getting accepted without funding doesn’t necessarily mean much!

I spent those years whilst I was applying gaining experience working as a research assistant in different universities. This extra experience (and name on papers) helped enormously to secure the funding I eventually took: a university-wide scholarship.

Each department only put forward one applicant (their strongest, supposedly) and from this department-wide pool only one scholarship was awarded. I certainly wouldn’t have been considered an outstanding applicant based off of just my undergraduate experience.

With some persistence it all worked out in the end. In hindsight I’m much happier with the project I ended up doing than if I’d gone for the one as intended at the start! Even so, it is easy to see how someone could have given up after the first failure in securing funding.

Application tips :

- Cast a wide net . Generally, more applications mean a higher chance of getting a funded project. Also, consider looking abroad. One of my regrets is not having applied for a PhD abroad, or at least tried to spend some time abroad as part of my project.

- Persistance pays off with PhD applications. If you like the work of certain researchers get in touch with them and stay in regular contact.

2) Failure in my basic biology knowledge at interview

Academic failure: Of my five PhD applications, I got rejected at interview stage for the Synthetic Biology CDT at Oxford.

It turned out that although the course was intended for non-biologists who were entering the field for the first time, I still didn’t have enough biology experience. One of the questions they asked was what DNA stood for: I didn’t have a clue!

Read about all my PhD interview experiences here .

Firstly, we can’t be good at everything!

Especially if you’re looking to change fields, it can be tricky to quickly get up to speed. This is particularly true when you have no idea what you’ll get asked at interview.

In my experience, once you start a PhD project it is actually a more forgiving environment, allowing you to build up your knowledge. So don’t worry too much that you need to know everything before you start. Even so, I felt like a bit of a failure walking out of that interview not being able to answer a relatively basic question!

Now I have a bit more experience I’d suggest demonstating your knowledge and capabilities with actual experience where you can.

I appreciate that this can be difficult but it could simply be a case of completeting a free online course. Doing so in my own field helped a lot with securing my current post-doc position. Having something tangible to support your application can go a long way. It also helps to slightly take the pressure off any awkward interview questions.

Academic Challenges During My PhD Project

Failing to reproduce published results.

Academic failure: For months I couldn’t acheive similar results to a previous study in the literature. The method was going to enable the main work of my PhD project and I had already spent a good chunk of my project budget trying to get it working. I was sure I was following the method precisely, and even emailed the authors looking for support. I never receied a reply and never did get the method working exactly as described in their paper.

Thankfully, after some more experimentation, we got a technique which worked. It even turned out to be better suited for our application than the method I was trying to reproduce. These developments lead to my first paper .

I got lucky that we found a method which worked before we ran out of money and time on the project. It could have gone very differently if we’d not tried other methods but it’s also worth saying how important it is to look to mitigate risks like this.

It is always worth being aware of how much time/money you have left. At an early stage start thinking “if I don’t have X done in Y weeks, we ought to look at doing something different”. Persistence is important with academic challenges but so is adapability.

- Is there someone in your group or university who already does what you’re trying to do? Be polite and make use of their expertise.

- Read a lot of literature to gain a solid understanding of the range of methods usually utilised. The ones which are used more often may be more reproducable and could be a good starting point.

- Reach out to authors of other studies but don’t expect them to reply.

- Try to iterate quickly to improve your chances of success.

- Make a plan B ! This is so important. Be prepared to pivot to something else if things don’t work out.

- Also, there is a reproducability issue in academia. At the very least when you come to write up your own research make sure to describe your methods in detail to help future researchers.

Failure to access equipment

Academic failure: A large part of my project depended on accessing a good quality micro-CT scanner and I didn’t have easy access to one. I spent months trying to find good reliable access. There were a few around the university but most groups and departments wanted to keep them to themselves.

I ended up using the one at the nearby Natural History Museum, and for the most part this worked out well. The only problem was that we had little control over it. We had to pay everytime we wanted to use it and had to book a slot months in advance. This all meant that I could only run a very limited number of experiments throughout my PhD: putting a lot of pressure on each set of scans and ultimately dissuading me from taking too many [potentially exciting] risks.

It really isn’t ideal to rely on equipment you only have very limited access to and there is high potential for it to cause significant academic challenges.

Mid way through my PhD I thought all my prayers had been answered when my supervisor won a big grant. This included provision to buy our very own posh micro-CT scanner. I still had a few years left of my PhD so it seemed like a sure bet that I’d make good use of it.

Well the procurement process for such an expensive bit of kit was painstakingly slow. The equipment eventually got delivered to a new campus in a building which still wasn’t finished by the end of my project. I failed to ever even see the scanner let alone use it!

There is so much potential for things to go wrong when you don’t have easy access to equipment. In hindsight I would have better utilised the equipment I had easy access to and made that the backbone of my project. Other results would have then been a bonus.

- Don’t rely on using equipment housed anywhere outside of your lab. During my time at Imperial, even communal equipment meant for researchers across all departments was moved off-site which has potential to cause complications.

- Even for equipment in your group, think about what you’d do if the equipment stopped working tomorrow and wasn’t fixed. This type of thinking can actually help you come up with new ideas which could be useful side-projects.

Failures to get research papers published in target journals

Academic failure: Numerous times I’ve failed to get papers published in journals we’ve submitted manuscripts to. For instance one paper which is currently under review was rejected by two other journals previously. Another we got published on our second or third attempt.

I try to see individual rejections of papers by journals as academic challenges as opposed to failures. It is great to be striving to publish your work and especially if you’re aiming for popular journals it is inevitable that you’ll face some rejections. It could be argued that if you never get papers rejected you’re not being ambitious enough!

I’ve written a whole series of posts about publishing and you can find them here: Writing an academic journal paper series .

As much as you can try to perfect a paper in preparation for submission, there is an element of luck. Different reviewers are looking for different things, and their opinion of your work will likely also vary a bit depending on the mood their feeling at the time. Even if you submitted the same paper multiple times to the same journal (note: don’t do this!) you’d likely get a range of decisions.

In my opinion it is only a failure if you don’t try at least try and get any of your work published!

Failure in rig design and testing: the time my rig started leaking salt water inside very pricy equipment!!

Academic failure: As mentioned in a previous section, my PhD project involved using a micro-CT scanner at the Natural History Museum.

I designed and built a new rig to enable me to do in-situ mechanical testing: basically apply force to biological samples during scanning. We had to keep the tissue samples hydrated in liquid at all times, including during scanning, and often used PBS : a salty water solution. I had tested the rig in our lab before taking it to the museum and it seemed to work as expected. I knew that I had to be able to leave the equipment because the experiments were at least eight hours long each (and ran continuously) and it wasn’t feasible to stay near the machine 24/7 even if I’d wanted to.

In my first set of experiments using it at the museum we got it all set up and running. I stayed for about 30 minutes to check there were no problems, then left to get on with some other work for the day. All seemed fine. A few hours later I got a message from the technician running the equipment to tell me that he thinks the liquid level is going down inside my rig!

I race over there, immediately take it out and pray that we haven’t caused any damage to the equipment. Miraculously there was no long term damage, but it was a very near miss. If the technician hadn’t spotted it things could have gone very differently! For reference the scanner cost the best part of £1 million… eek!

Thankfully the problem with my rig was quick to fix but it would have been far better to avoid these issues in the first place.

- Double, triple or quadruple check that equipment is working as expected: especially for rigs and devices you’ve designed!!

- Mitigate risks. In my case, once we thought we’d resolved the issue we did a few more experiments with paper towel taped around the rig to ensure any spills would be soaked up. Yes, really.

Failure to stand my ground

Academic failure: for the most part I was lucky to not have many disagreements and regrets from my PhD. Even so, there are a few instances where in hindsight I wish I had held my ground and put a bit more thought into making sure I was getting the right outcome for myself and/or the research.

To give a tangible example: in the rush as I was finishing up my project I had to decide on a title for my PhD. I worked through some ideas with my main supervisor and someone else chimed in to take the title in a different direction which my supervisor said he thought was a good idea.

We met in the middle with a hybrid title. Soon after finishing up I regretted the choice but by then it was too late to make any changes so I’m stuck with what we chose. The title isn’t awful and it doesn’t need to define my PhD, but even so I do regret not putting in a bit more thought to what I wanted and diplomatically standing my ground.

Pick your battles, but do stand up for yourself. It is your PhD!

Bonus: failing to get elected to lead a student society (twice)

Not related to academic work, but I’ll include it as part of my time at university during my PhD.

The failure: I wanted to get involved with a student society which had disbanded by the time I joined the university. Myself and a few others started it back up again and I was keen to lead it.

I applied for the role of president and got rejected.

I ran for the position again the following year and got rejected for a second time.

Finally, as I was entering my final full PhD year, I got in on the third and final attempt!

Stick with something. Or maybe know when to move on?!

How to Deal with Academic Challenges During Your PhD

Reframing academic failure.

Facing academic challenges is part of the PhD process. If you’re doing something new it is inevitable that things will not go perfectly the first time. In fact, if things appear to have gone perfectly it more than likely means that something is wrong.

Despite the name of this post, try to think of these issues as challenges to overcome rather than failures. An academic challenge only becomes a failure if you’ve not made a reasonable effort to overcome the obstacle. For example, if you ignore something for several months or don’t tell your supervisor about it, then what could have been an easy fix can become a much bigger issue.

You’ll find it much easier to deal with something when it is framed as a research challenge, which can be exciting to overcome, rather than considering every setback as a personal failure.

I’d say that one of the most important parts of a PhD is to learn from your mistakes. This is an integral part of the PhD process and you’ll only be able to do this when you can objectively assess how things are going. Please don’t fall into the depressing valley of thinking about your work as a failure.

How to Mitigate the Risks of Academic Failure During Your PhD

- Communicate regularly with your supervisor. Communicating openly and often with your supervisor will ensure you’re both working together effectively as a team. Your supervisor should be a source of motivation and provide guidance on any academic challenges where necessary. If you meet regularly you can stop potential PhD problems in their tracks before they become big issues. I found meeting weekly to work well. If your supervisor is often too busy to meet that should be a warning sign which should also be addressed.

- Know the literature thoroughly . For most research topics, you’re not the first person to have asked the questions you’re looking to solve. Find out where other people have got to and build up your research from this. We can’t be experts in everything, but you should know how other researchers have conducted similar experiments to you. This should help you both to avoid academic failures and have a solid starting point from which you can begin adding your own twist – saving you months of headaches.

- Work hard but work smart . Certain academic challenges can be overcome simply by putting in the necessary effort. Check that equipment is working ahead of when you need it, do all the necessary calibration as often as necessary and don’t shy away from the effort required to try out different experimental procedures. But on the other hand, don’t work aimlessly otherwise you risk burning out. Work smart which ties in with the next point: planning.

- Make a plan. Know when you need to have achieved certain milestones by in order to stay on track. Mitigate risks by thinking about alternative routes of research in case things go wrong.

- Cut yourself some slack . We all make mistakes, don’t stress yourself out too much about small errors. Try to keep a level head and stay in a mindset where problems with your PhD don’t get you down too much. As long as you are making efforts to develop your skills and seeking to get closer to answering your research questions you’re on the right path.

I really hope that content such as this is useful in normalising academic failure. It is completely normal for problems to occur, but it is how you deal with these academic challenges which will define your PhD. Best of luck.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

The Five Most Powerful Lessons I Learned During My PhD

8th August 2024 8th August 2024

Minor Corrections: How To Make Them and Succeed With Your PhD Thesis

2nd June 2024 2nd June 2024

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 4th August 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

After horrible 5.5 years completely failed PhD (not even any degree awarded)

Hi, I started my PhD in 2012, on my first day I already got warned to be careful with my supervisor. Having had quite bad supervisors in the past (the ‘fat girls are stupid’ kind and the ‘you aren’t my favourite so I do not help you’ kind) I figured at this stage I’m fine I was well used to it. Now, 1 car crash, bullying, address to the lab withdrawn then lack of results blamed on being stupid, almost 6 years later I suffer from depression, have ongoing nightmares and not even any kind of participation badge for all the time in the lab and- frankly, therapy. I agree that the thesis was bad but I do find it an odd coincidence that I was told I was going to pass, until I filed an academic and dignity complaint against my supervisors (with evidence) and now I am supposed to get more experimental results (without lab access) and am supposed to improve my bad writing... I know I am not stupid but I feel bad I been given the materials, the access and the support that was advertised and had they listened when Initially discussed the lack of biological relevance and scientific depth when I requested a switch from topic- i feel I would have at least gotten an MPhil. After refusing a switch in topic or supervisors because ‘there is no time to get enough results with only 3 years left’ they then switched my topic with only little under 2 years left, which suddenly was more than enough time. At the same time I was told I was useless unless I went part-time but worked on the thesis full-time and came in every weekend (while blocking my out of hours access???) The thesis was bad and I said it from the beginning but was always told I was doing Phantastin with a paper on the way (until the complaint...when oddly suddenly I failed and had tons of obstacles thrown my way) How do I get over this?

You are supposed to get more results, or they have failed you outright? Has this been through the board of examiners? There are still steps you can take to rectify this is you want to. You can appeal the decision, if you have grounds do so, e.g. if there was "material irregularity in the decision making process", such as they didn't follow the procedures properly, or there were errors made, if your performance was affected by something you haven't disclosed or they failed to take account of it properly (maybe the latter in your case?). Seek advice from the Students' Union If you just want to forget it about it, then I suggest getting a change of scene, go on holiday, or go and stay with friends/family somewhere. Time and distance will give you some perspective. Failing that, try some counselling. It does sound like you have had a raw deal here and this should be a lesson to anyone that is thinking about registering a complaint about supervisors - it generally does not have a good outcome and is best left until your certificate is safely in your hand.

Hi, Just finished crying and reading through the notes. I was failed outright (no viva) but was given the option to resubmit in 1 year with a mandatory viva (perfectly fair enough) but they want more data. How can I possibly get more data without access to the laboratory? They blocked my access long before submission, I didn‘t even have library access. Thanks for the student union tip, I have raised that the internal examiner is one of my supervisors closest friends but I am am still shattered. How is one supposed to get good data without laboratory access, out of hour access revoked almost 1 year before writing period started and no access to materials needed for cloning without arguing for weeks? Such a long time, such a long gap in my CV and so much bad treatment all for nothing :(

Hi, Tigernore, You have my sympathy. Working under a bullly supervisor is awful and you have not been given fair treatment. As Tree of Life has advised, seek the Students Union. In fact, see if your Students Union provide legal services. You have nothing to lose anyway, and talking to a lawyer will help you determine if any rules have been broken incl the right access to lab support and material as a student. It will also put pressure on the university as they normally do not want anything that may damage their reputation, especially if they are in the wrong. You may even be able to fight for lab access again and another fair examination of your thesis. Dry your tears. Now is the time for desperate actions and strategy. You must stay strong. What your supervisor and examiners want to do is to force you to give up and walk away, painting you as a bad student. You must not let them win. I speak from my personal experience as I too launched a complain towards my supervisor and the amount of backlash and soft threats (veiled as advice to maintain good relationship with supervisor as I need his letter of support) were terrible. I represented myself at institute level -failed, faculty level -failed and finally University level -success with a detailed portfolio of evidence and cover letter provided with strong support from a lawyer from Students Union. In my case, I had very strong evidence and was advised by my lawyer that if I failed again at university level, I could go to court. Luckily I didn't have to but the experience was traumatic. Every case is different, and I wish you the very best as you fight for yours. Don give up without trying to fight.

I would echo what tru has said as well. This is not over yet if you don't want it to be. They have to give you lab access if they are asking for more results. Cutting your access to things doesn't seem fair - you should check if this happens to all students in your department - if doesn't, you have a massive case for mistreatment because they have been setting you up to fail. Who has signed off on this decision? Examiners? Head of postgrads? Head of School? Faculty Dean? Take up to a higher level if needed. Don't cry about this, get angry instead. Channel that anger into getting the access and then the results you need to get this PhD.

Hi, I know of multiple students having had ...let's say issues in my department. Including sexual harrassment and when filed being threatened with losing the degree, having no right to holidays and having the same issue I have of being told to go part-time (including part-time stipend) but working full-time in the lab-which most cannot afford. I just can't seem to get heard, everyone is just saying, well let it go they have the power etc. And without access to labs like you agree I can't get anywhere and I don't even have a supervisor / academic tutor at this point. I am filing my appeal over this week and requesting await of the complaint process and readjustment of my access. It is impossible to salvage this into a PhD with what happened but at least an MPhil would have been nice. Thanks for your messages!!!

Quote From Tigernore: Hi, I know of multiple students having had ...let's say issues in my department. Including sexual harrassment and when filed being threatened with losing the degree, having no right to holidays and having the same issue I have of being told to go part-time (including part-time stipend) but working full-time in the lab-which most cannot afford. I just can't seem to get heard, everyone is just saying, well let it go they have the power etc. And without access to labs like you agree I can't get anywhere and I don't even have a supervisor / academic tutor at this point. I am filing my appeal over this week and requesting await of the complaint process and readjustment of my access. It is impossible to salvage this into a PhD with what happened but at least an MPhil would have been nice. Thanks for your messages!!! Ah, the usual discouragement.. "Let go because you can't win.. Why bother since your supervisors have power..." Haven't we all heard of that before... This is the phsycological game to break the student's spirit and rid "troublemakers".. Don't give in. Tigernore, steel yourself. You have not been given a fair fighting chance, and you know it. Instead of talking to nonsense people who are out to discourage you (probably other academics who may or may not have ties with your uni and supervisor), talk to your Student Union who is supposed to defend you. Talk to a legal representative from your Student Union. Fight for your PhD... All is not lost unless you give up on yourself. All the best in your appeal, and don't walk away without exhausting all avenues.

I agree with Tru, I am going through a fight of my own at the moment and experienced the psychological games. I am very much on my own and have been working without supervision for 6 months now, I am almost 12 months in. Having no supervision is better than the situation I was in, but it can't continue for long this way, so I am hoping for a resolution soon. Dragging things out seems to be another way of trying to get rid of any student who speaks out. I have a strong case and its sounds like you have also, so as Tru also says don't give in. My SU haven't been any help, they often don't respond and don't seem to know processes well. Your SU may be better so I advise speaking to them. I struggled getting heard also, my department seemingly didn't want to know, so it had to go formal. I also have/had a supervisor you have to be careful with and my project was changed after I started. So I sympathise with your situation. I see many similarities on this forum among experiences students have concerning supervisor issues and how Universities respond to such cases.

Post your reply

Postgraduate Forum

Masters Degrees

PhD Opportunities

Postgraduate Forum Copyright ©2024 All rights reserved

PostgraduateForum Is a trading name of FindAUniversity Ltd FindAUniversity Ltd, 77 Sidney St, Sheffield, S1 4RG, UK. Tel +44 (0) 114 268 4940 Fax: +44 (0) 114 268 5766

Welcome to the world's leading Postgraduate Forum

An active and supportive community.

Support and advice from your peers.

Your postgraduate questions answered.

Use your experience to help others.

Sign Up to Postgraduate Forum

Enter your email address below to get started with your forum account

Login to your account

Enter your username below to login to your account

Reset password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password

An email has been sent to your email account along with instructions on how to reset your password. If you do not recieve your email, or have any futher problems accessing your account, then please contact our customer support.

or continue as guest

Postgrad Forum uses cookies to create a better experience for you

To ensure all features on our website work properly, your computer, tablet or mobile needs to accept cookies. Our cookies don’t store your personal information, but provide us with anonymous information about use of the website and help us recognise you so we can offer you services more relevant to you. For more information please read our privacy policy

Dealing with failure as a PhD student

PhD students are extremely prone to experiencing failure. All academics are much more likely to experience failure (repeatedly) in contrast to other professions. But there are strategies to learn how to better deal with ‘academic failure’.

Dealing with failure in academia

PhD students can deal with failure more constructively by realizing that failures are an inevitable part of academic work.

Additionally, the following strategies help to deal with failure and build lasting resilience:

What counts as ‘academic failure’?

In this article, the authors address failure as something that is not in line with desired or expected results. This definition draws attention to the emotions and individual experiences of failures. What constitutes a failure for one person, might not be considered a failure by another.

The highly subjective character of perceiving failure also provides hope. While rejections and negative feedback are never pleasant, we can learn to redefine what we see as a failure and build resilience.

#1. Understand that all academics encounter failure

Academics also regularly apply for grants and project funding. Competition for many grants and scholarships is extremely high. The acceptance rate of many grants lies below 5%!

#2. Celebrate your courage to take risks

Celebrating successes is great. However, when it comes to long-term resilience building, it draws attention to the wrong outcome. Instead of (only) celebrating your successes, start celebrating your courage to take risks.

#3. Openly share and discuss your failures

In 2016, Professor Johannes Haushofer from Princeton University went viral with what he called his “CV of failures” . Instead of listing his successes, he compiled an honest resumé that included everything he tried to achieve but failed to do so. It included job applications, research funding applications and paper rejections.

Knowing that you are not alone in this and that everyone fails once in a while, helps enormously. And similarly to celebrating your courage, celebrating your colleagues’ milestones. Praise ‘trying’ over ‘succeeding’.

#4. Give yourself time to grieve

At the same time, there is some truth to it. Just because you consciously know that failures are part of academic life, are normal and will ultimately help you to grow as an academic, you still need to take the proper time to allow for emotional processing.

#5. Find a good academic mentor

If you experience failure, you should talk to your academic mentor. Explain how you feel. How crushed you are. If you respect the opinion of your mentor, you will also believe their honest assessment of the quality of your work.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox, energy management in academia, dealing with conflicting feedback from different supervisors, related articles, 37 creative ways to get motivation to study, clever strategies to keep up with the latest academic research, the best way to cold emailing professors, introduce yourself in a phd interview (4 simple steps + examples).

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 21 August 2023

Failed PhD: how scientists have bounced back from doctoral setbacks

- Carrie Arnold 0

Carrie Arnold is a science writer based near Richmond, Virginia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Distraught and panicking, Jess McLaughlin logged into their Twitter account last October and wrote a desperate, late-night tweet .

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 620 , 911-912 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02603-8

Related Articles

- Scientific community

Massive Attack’s science-led drive to lower music’s carbon footprint

Career Feature 04 SEP 24

Tales of a migratory marine biologist

Career Feature 28 AUG 24

Nail your tech-industry interviews with these six techniques

Career Column 28 AUG 24

Guide, don’t hide: reprogramming learning in the wake of AI

Career Guide 04 SEP 24

What I learnt from running a coding bootcamp

Career Column 21 AUG 24

The Taliban said women could study — three years on they still can’t

News 14 AUG 24

How can I publish open access when I can’t afford the fees?

Career Feature 02 SEP 24

Faculty Positions in School of Engineering, Westlake University

The School of Engineering (SOE) at Westlake University is seeking to fill multiple tenured or tenure-track faculty positions in all ranks.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Postdoctoral Associate- Genetic Epidemiology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

NOMIS Foundation ETH Postdoctoral Fellowship

The NOMIS Foundation ETH Fellowship Programme supports postdoctoral researchers at ETH Zurich within the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life ...

Zurich, Canton of Zürich (CH)

Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich

13 PhD Positions at Heidelberg University

GRK2727/1 – InCheck Innate Immune Checkpoints in Cancer and Tissue Damage

Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg (DE) and Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg (DE)

Medical Faculties Mannheim & Heidelberg and DKFZ, Germany

Postdoctoral Associate- Environmental Epidemiology

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Remember me Not recommended on shared computers

Forgot your password?

- Coursework, Advising, and Exams

failing out of grad school!!

By tomyum October 26, 2011 in Coursework, Advising, and Exams

Recommended Posts

I am a first year Phd student in chemistry and I am having a very hard time in my courses in grad school. I did pretty badly in my midterms despite studying really hard. In one of my classes I am so lost, I don't understand anything at all and I am certain that I will fail it. I need to maintain a B average, otherwise I will get kicked out of the program. I had a near perfect GPA in undergrad, got accepted into most of the top ranking graduate schools that I applied to, and I thought I was smart enough for grad school but now I feel like I am very under-prepared/ not smart enough for grad school . I went to a small school and did liberal arts, so I think my background is not strong enough. Has anyone been kicked out of grad school after failing to maintain the minimum grade point average? I asked a couple of people at my school and most of them say that it is pretty impossible to fail out of a Phd unless you deliberately try to. I really don't know how true that is.

Link to comment

Share on other sites.

There are people in my program that have been on "academic probation" for quite a while due to low grades.

What it comes down to is the stuff outside of classes- if your coursework isn't up to par, but your research is good, you're on a lot better footing. Does your school have rotations? How are yours going?

Also, from my coursework experience, the percent grades on all of our tests were bad. Really bad. Like 30-40 as an average bad. Have the professors talked at all about how they're going to end up assigning grades? How are other people doing? Studying with people from your cohort can really help- a lot of you are probably taking most of the same classes, so you can study together for more than one thing.

The last thing I'll ask is how many classes you're taking- I think a lot of first semester students take too many, and in addition to teaching and research it really bogs them down.

I am in the same boat as you. I need a 3.2 to even take the qualifying exams which students usually take after their first semester. I have heard that it is damn near impossible to fail since the professors will try to help you out. My professors will forget about the midterm if significant improvement is shown on the final.

On a similar note, I too feel extremely underprepared since almost everyone else have taken the classes I'm taking already.

Eigen: Thanks for the reply! yes, my school has rotations and they have been going really well so far. I really enjoy being in the lab. I am taking four courses but only two of them are chemistry courses, the other two are seminar style pass/fail courses which just require attendance. I do study with my classmates, they are really collaborative and nice and we work on the problem sets together. But the classmates that I work with already have masters degree or have taken similar undergrad courses so are much more better prepared. The prof. has not said how he is going to grade the midterms but my percentage grade is really low. I only made a 37 out of 100 in one of my exams.

Eisenmann: it feels nice to know that I am not the only one who is really worried about grades in grad school! Everyone around me seems to be so much more prepared for grad school. I wish you good luck with your graduate work.

Have you talked to the professor(s) for these classes?

I'd just be honest, assuming you think they're decent people- ask if you can talk about the midterm, and lay out your worries. Mention that you haven't had a lot of similar material as an undergrad, and it just seems like you're having a hard time playing catch up in addition to learning the new material- and see what they say. They might have some helpful study suggestions for you, additional works that might bridge the gap- or they may say you're not failing according to how they're planning on grading at the end.

If you want to PM me a bit more about the courses you're taking, I might have some suggestions. Some courses are just brutal overall.

- Sigaba and tomyum

Genomic Repairman

Yes, we have had a couple of grad students get bounced out for grades. I like to think that grades can only hurt you, not help you. And what I mean by that is in graduate school (in so far as the sciences) you are really gauged on how productive you are, not how good your course work was. You just need to do good enough to get by so far as grades.

If you tank a class and go on academic probation, so what, just repeat it. It sucks, but it is not the end of the world, even though it may seem as much right now. Keep your chin up.

- MoJingly and tomyum

Yes, we have had a couple of grad students get bounced out for grades. I like to think that grades can only hurt you, not help you. And what I mean by that is in graduate school (in so far as the sciences) you are really gauged on how productive you are, not how good your course work was. You just need to do good enough to get by so far as grades. If you tank a class and go on academic probation, so what, just repeat it. It sucks, but it is not the end of the world, even though it may seem as much right now. Keep your chin up.

Thanks for the encouraging words! I am hanging in there. On top of academic stress, graduate school is very lonely. There is so much work that I really don't have time to socialize and make good friends. I had a really good group of friends as an undergrad, and despite the pressure of school work, it was okay because I had a really supportive social life. But now if some small thing goes wrong, I totally panic and I keep thinking about it. Moving to a new city, loneliness and academic pressure - all of this is very hard to deal with. I used to eat in dining hall in my undergrad, so there were always people around and it was nice. Now I don't even feel like eating as eating alone is so depressing. I have lost a lot of weight since I joined grad school. I hope things with get better but I feel so helpless. These two month have been really hard. Does grad school get any better after the first year/ after completing course requirements?

You have to make time for some type of friend outside of your classmates, you know normal folks. They help to keep you grounded and give you a sense of perspective that is lost in the lab grind by the rest of us. For instance, I used to drink beer with the night janitor while getting my MS. When 11pm rolled around, I'd stop what I'd be doing and we would walk the halls drinking Bud Lights in koozies, bullshitting, and I'd help him empty the trash. I'd tell him about my problems, he'd tell me his, I'd explain my project to him, and he would ask me why I was doing something. I still miss our evening constitutionals, where we discussed life, science, why the PI down the hall was such a bitch, and whose turn it was to buy beer.

Moral of the Story: Make some damn time for friends. You are never going to have balance all the time in your graduate career. At some points you will feel like you are spending too much time in the lab or too much time on your personal life. That's fine, just let it balance out in the long run. How many scientists were there 200 years ago? A shit ton son! How many can we name? Not too many. Science is not your life, its something you are passionate about and do to live your life. Enjoy the people around you and let them enjoy you.

Now get your ass out of the lab and make friends. Oh and study too.

- NinjaMermaid , Ennue , Safferz and 6 others

Hang in there. You can do it!

Remember that your department believes in you, your ability to work hard, and your potential--otherwise they'd not have offered you admission. Your department believes in you. Trust their wisdom. It wasn't by accident that they said "Come, be one of us."

Right now, the learning curve looks steep because you're building upon your previous experiences to build new skill sets. As formidable as the new terrain may seem, you have it within you to figure out ways to navigate it successfully.

Let go of fear. Your legs are shaky now. Yet visualize yourself on that day in the not so distant future when you'll be running, looking over your shoulder, and laughing "Hey, slowpokes, keep up!" You can do it.

Now, in addition to the options outlined above, please consider the utility of the following.

Get to know some of your professors. As they have been there and done that, they know what you're going through. Among them may be a professor or two who can offer words of wisdom, an empathetically appropriate response, and maybe even friendship. (If a friendship does develop, keep the boundaries clear in your own mind. And remember that empathy is different than sympathy.)

Get to know some of the grad students who have been around a while. They may know some tricks of the trade that will benefit you.

Carve out some "me time" in your schedule. As an example, when I was doing my coursework, the interval between the end of my last class of the week and the evening of the following day was mandatory decompression time. Concurrently, I made a commitment to watching most of my favorite team's games--no matter what.

If you do designate "me time," consider a counter-programing approach. For instance, if you're going to have a "Friday night" make that night Wednesday. This way, you'll have to deal with less traffic at popular venues.

Carve out some discretionary funds in your budget. I know times are hard and the life of a graduate student can be austere. But designate a certain amount for certain activities and then pursue those activities. As an example, budget fifty bucks a month for music and/or a similar amount for Starbucks. Spend some of your "me time" leisurely spending your money. (Alternatively, you could get some magazine subscriptions at the student rate.)

- Ennue , waddle , Genomic Repairman and 3 others

mikeprefecture

I am on the same boat. I am in the first semester of my first year in a Canadian PhD program. I just received my midterms results in one of my subjects yesterday and it was very discouraging. I got a grade of C+, the problem set that I did for the same subject was given a grade of B-. The minimum grade that is needed for each course to continue to the program is B. I know I have given everything that I have for both the exam and the problem set, I have no idea what else to give.

I am doing well in other subjects that I am taking though. I got grades of A's in the midterms and problem sets for my other subjects. My adviser keeps asking about how my subjects are doing and was very pleased with how I performed in other subjects. When she asked me yesterday about the subject that I failed, I told her I didn't know the result yet which was the truth since I have just gotten the midterms back after I met with her. I am so ashamed now to tell her about this. This drove my confidence to the sink as well as I am not used to failing. I feel very discouraged now.

Should I drop the course? Should I keep it from my advisor until the final grade is released? Any advice on how to deal with this? I will be kicked out of the program if I fail this course.

I am on the same boat. I am in the first semester of my first year in a Canadian PhD program. I just received my midterms results in one of my subjects yesterday and it was very discouraging. I got a grade of C+, the problem set that I did for the same subject was given a grade of B-. The minimum grade that is needed for each course to continue to the program is B. I know I have given everything that I have for both the exam and the problem set, I have no idea what else to give. I am doing well in other subjects that I am taking though. I got grades of A's in the midterms and problem sets for my other subjects. My adviser keeps asking about how my subjects are doing and was very pleased with how I performed in other subjects. When she asked me yesterday about the subject that I failed, I told her I didn't know the result yet which was the truth since I have just gotten the midterms back after I met with her. I am so ashamed now to tell her about this. This drove my confidence to the sink as well as I am not used to failing. I feel very discouraged now. Should I drop the course? Should I keep it from my advisor until the final grade is released? Any advice on how to deal with this? I will be kicked out of the program if I fail this course.

You should talk to your adviser now. You should also talk to the professor that is teaching the course. Since you are doing well in all your other subjects, they will likely want to do everything possible to help you pass so that you don't get kicked out. Hiding it until you fail is not going to help.

- Sigaba and Ennue

I want to make friends with the night janitor. Would it be creepy if I showed up with beer some night and say, "hey, be my friend!" ?

tomyum, I've been hitting many of the same problems you've been facing, and I'm just barely hanging on. Today, when lab work was going horrendously as usual, I started listing out each obstacle I've run into as a beginning grad student, and coming up with possible solutions for each--baby steps.

It's wonderful how much support this forum provides!

P.S. I've been lurking in the Earth Sci. forum but I think I'm going to get back to posting more-or-less regularly now.

I want to make friends with the night janitor. Would it be creepy if I showed up with beer some night and say, "hey, be my friend!" ? Also, Sigaba.... amazing post

tomyum, I've been hitting many of the same problems you've been facing, and I'm just barely hanging on. Today, when lab work was going horrendously as usual, I started listing out each obstacle I've run into as a beginning grad student, and coming up with possible solutions for each--baby steps. It's wonderful how much support this forum provides! P.S. I've been lurking in the Earth Sci. forum but I think I'm going to get back to posting more-or-less regularly now. Do it!

Tall Chai Latte

I failed a class last semester and am placed on academic probation this semester. I also studied very hard and talked to the professor for suggestions, but in the end I still failed... Now I need to repeat this class to in order take the candidacy exam next year. I have to say that grades are still important because you need them to apply for external funding and moving along in your program. However, while a C on the transcript seems bad, it's really not the end of the world. Grad school is just a process, don't stress yourself out over a printed letter.

You have to let it happen organically, you could just drink booze in the lab and offer some up to the janitor, public safety, or the hobo trying to steal shit from the lab whenever the opportunity presents itself.

- 3 weeks later...

NinjaMermaid

You have to make time for some type of friend outside of your classmates, you know normal folks. They help to keep you grounded and give you a sense of perspective that is lost in the lab grind by the rest of us. For instance, I used to drink beer with the night janitor while getting my MS. When 11pm rolled around, I'd stop what I'd be doing and we would walk the halls drinking Bud Lights in koozies, bullshitting, and I'd help him empty the trash. I'd tell him about my problems, he'd tell me his, I'd explain my project to him, and he would ask me why I was doing something. I still miss our evening constitutionals, where we discussed life, science, why the PI down the hall was such a bitch, and whose turn it was to buy beer. Moral of the Story: Make some damn time for friends. You are never going to have balance all the time in your graduate career. At some points you will feel like you are spending too much time in the lab or too much time on your personal life. That's fine, just let it balance out in the long run. How many scientists were there 200 years ago? A shit ton son! How many can we name? Not too many. Science is not your life, its something you are passionate about and do to live your life. Enjoy the people around you and let them enjoy you. Now get your ass out of the lab and make friends. Oh and study too.

I would like to say that I approve of this advice. =)

I think you need to talk to your professors first. Most professors don't want to see you fail, especially if they see that you really are trying (and lab work proves that). Explain to them that you're playing catch up and so on.

Also, try to make some friends. Feeling depressed and lonely will have a negative effect on your work regardless of how hard you try otherwise.

- 2 weeks later...

Don't graduate students have the power to drop a class all the way up to the last day of classes?

Not that I've ever seen. Our registration works just like undergrads, same dates etc.

We get an extra week to drop classes compared to the undergrads. I imagine that's because many graduate courses only meet once per week.

Then I guess UIUC and UCSB are one of the few graduate programs that allow graduate students to drop their classes all the way up to the last day of classes.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Already have an account? Sign in here.

- Existing user? Sign In

- Online Users

- All Activity

- My Activity Streams

- Unread Content

- Content I Started

- Results Search

- Post Results

- Leaderboard

- Create New...

Important Information

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. See our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

- PhD Failure Rate – A Study of 26,076 PhD Candidates

- Doing a PhD

The PhD failure rate in the UK is 19.5%, with 16.2% of students leaving their PhD programme early, and 3.3% of students failing their viva. 80.5% of all students who enrol onto a PhD programme successfully complete it and are awarded a doctorate.

Introduction

One of the biggest concerns for doctoral students is the ongoing fear of failing their PhD.

After all those years of research, the long days in the lab and the endless nights in the library, it’s no surprise to find many agonising over the possibility of it all being for nothing. While this fear will always exist, it would help you to know how likely failure is, and what you can do to increase your chances of success.

Read on to learn how PhDs can be failed, what the true failure rates are based on an analysis of 26,067 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities, and what your options are if you’re unsuccessful in obtaining your PhD.

Ways You Can Fail A PhD

There are essentially two ways in which you can fail a PhD; non-completion or failing your viva (also known as your thesis defence ).

Non-completion

Non-completion is when a student leaves their PhD programme before having sat their viva examination. Since vivas take place at the end of the PhD journey, typically between the 3rd and 4th year for most full-time programmes, most failed PhDs fall within the ‘non-completion’ category because of the long duration it covers.

There are many reasons why a student may decide to leave a programme early, though these can usually be grouped into two categories:

- Motives – The individual may no longer believe undertaking a PhD is for them. This might be because it isn’t what they had imagined, or they’ve decided on an alternative path.

- Extenuating circumstances – The student may face unforeseen problems beyond their control, such as poor health, bereavement or family difficulties, preventing them from completing their research.

In both cases, a good supervisor will always try their best to help the student continue with their studies. In the former case, this may mean considering alternative research questions or, in the latter case, encouraging you to seek academic support from the university through one of their student care policies.

Besides the student deciding to end their programme early, the university can also make this decision. On these occasions, the student’s supervisor may not believe they’ve made enough progress for the time they’ve been on the project. If the problem can’t be corrected, the supervisor may ask the university to remove the student from the programme.

Failing The Viva

Assuming you make it to the end of your programme, there are still two ways you can be unsuccessful.

The first is an unsatisfactory thesis. For whatever reason, your thesis may be deemed not good enough, lacking originality, reliable data, conclusive findings, or be of poor overall quality. In such cases, your examiners may request an extensive rework of your thesis before agreeing to perform your viva examination. Although this will rarely be the case, it is possible that you may exceed the permissible length of programme registration and if you don’t have valid grounds for an extension, you may not have enough time to be able to sit your viva.

The more common scenario, while still being uncommon itself, is that you sit and fail your viva examination. The examiners may decide that your research project is severely flawed, to the point where it can’t possibly be remedied even with major revisions. This could happen for reasons such as basing your study on an incorrect fundamental assumption; this should not happen however if there is a proper supervisory support system in place.

PhD Failure Rate – UK & EU Statistics

According to 2010-11 data published by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (now replaced by UK Research and Innovation ), 72.9% of students enrolled in a PhD programme in the UK or EU complete their degree within seven years. Following this, 80.5% of PhD students complete their degree within 25 years.

This means that four out of every five students who register onto a PhD programme successfully complete their doctorate.

While a failure rate of one in five students may seem a little high, most of these are those who exit their programme early as opposed to those who fail at the viva stage.

Failing Doesn’t Happen Often

Although a PhD is an independent project, you will be appointed a supervisor to support you. Each university will have its own system for how your supervisor is to support you , but regardless of this, they will all require regular communication between the two of you. This could be in the form of annual reviews, quarterly interim reviews or regular meetings. The majority of students also have a secondary academic supervisor (and in some cases a thesis committee of supervisors); the role of these can vary from having a hands-on role in regular supervision, to being another useful person to bounce ideas off of.

These frequent check-ins are designed to help you stay on track with your project. For example, if any issues are identified, you and your supervisor can discuss how to rectify them in order to refocus your research. This reduces the likelihood of a problem going undetected for several years, only for it to be unearthed after it’s too late to address.

In addition, the thesis you submit to your examiners will likely be your third or fourth iteration, with your supervisor having critiqued each earlier version. As a result, your thesis will typically only be submitted to the examiners after your supervisor approves it; many UK universities require a formal, signed document to be submitted by the primary academic supervisor at the same time as the student submits the thesis, confirming that he or she has approved the submission.

Failed Viva – Outcomes of 26,076 Students

Despite what you may have heard, the failing PhD rate amongst students who sit their viva is low.

This, combined with ongoing guidance from your supervisor, is because vivas don’t have a strict pass/fail outcome. You can find a detailed breakdown of all viva outcomes in our viva guide, but to summarise – the most common outcome will be for you to revise your thesis in accordance with the comments from your examiners and resubmit it.

This means that as long as the review of your thesis and your viva examination uncovers no significant issues, you’re almost certain to be awarded a provisional pass on the basis you make the necessary corrections to your thesis.

To give you an indication of the viva failure rate, we’ve analysed the outcomes of 26,076 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities who sat a viva between 2006 and 2017.

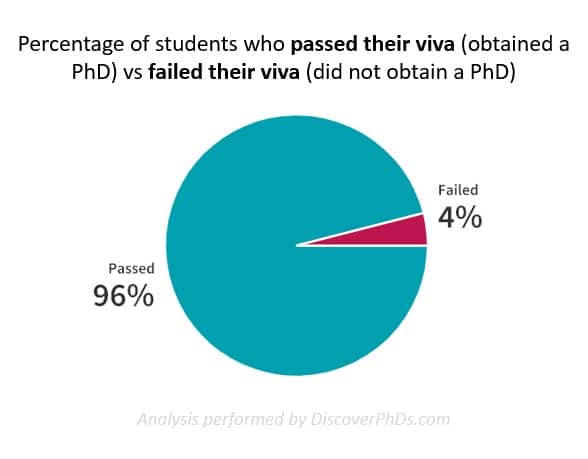

The analysis shows that of the 26,076 students who sat their viva, 25,063 succeeded; this is just over 96% of the total students as shown in the chart below.

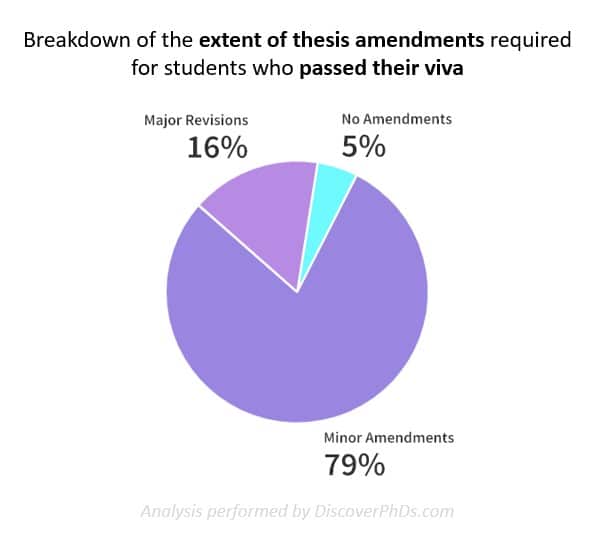

Students Who Passed

The analysis shows that of the 96% of students who passed, approximately 5% required no amendments, 79% required minor amendments and the remaining 16% required major revisions. This supports our earlier discussion on how the most common outcome of a viva is a ‘pass with minor amendments’.

Students Who Failed

Of the 4% of unsuccessful students, approximately 97% were awarded an MPhil (Master of Philosophy), and 3% weren’t awarded a degree.

Note : It should be noted that while the data provides the student’s overall outcome, i.e. whether they passed or failed, they didn’t all provide the students specific outcome, i.e. whether they had to make amendments, or with a failure, whether they were awarded an MPhil. Therefore, while the breakdowns represent the current known data, the exact breakdown may differ.

Summary of Findings

By using our data in combination with the earlier statistic provided by HEFCE, we can gain an overall picture of the PhD journey as summarised in the image below.

To summarise, based on the analysis of 26,076 PhD candidates at 14 universities between 2006 and 2017, the PhD pass rate in the UK is 80.5%. Of the 19.5% of students who fail, 3.3% is attributed to students failing their viva and the remaining 16.2% is attributed to students leaving their programme early.

The above statistics indicate that while 1 in every 5 students fail their PhD, the failure rate for the viva process itself is low. Specifically, only 4% of all students who sit their viva fail; in other words, 96% of the students pass it.

What Are Your Options After an Unsuccessful PhD?

Appeal your outcome.

If you believe you had a valid case, you can try to appeal against your outcome . The appeal process will be different for each university, so ensure you consult the guidelines published by your university before taking any action.

While making an appeal may be an option, it should only be considered if you genuinely believe you have a legitimate case. Most examiners have a lot of experience in assessing PhD candidates and follow strict guidelines when making their decisions. Therefore, your claim for appeal will need to be strong if it is to stand up in front of committee members in the adjudication process.

Downgrade to MPhil

If you are unsuccessful in being awarded a PhD, an MPhil may be awarded instead. For this to happen, your work would need to be considered worthy of an MPhil, as although it is a Master’s degree, it is still an advanced postgraduate research degree.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of stigma around MPhil degrees, with many worrying that it will be seen as a sign of a failed PhD. While not as advanced as a PhD, an MPhil is still an advanced research degree, and being awarded one shows that you’ve successfully carried out an independent research project which is an undertaking to be admired.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Additional Resources

Hopefully now knowing the overall picture your mind will feel slightly more at ease. Regardless, there are several good practices you can adopt to ensure you’re always in the best possible position. The key of these includes developing a good working relationship with your supervisor, working to a project schedule, having your thesis checked by several other academics aside from your supervisor, and thoroughly preparing for your viva examination.

We’ve developed a number of resources which should help you in the above:

- What to Expect from Your Supervisor – Find out what to look for in a Supervisor, how they will typically support you, and how often you should meet with them.

- How to Write a Research Proposal – Find an outline of how you can go about putting a project plan together.

- What is a PhD Viva? – Learn exactly what a viva is, their purpose and what you can expect on the day. We’ve also provided a full breakdown of all the possible outcomes of a viva and tips to help you prepare for your own.

Data for Statistics

- Cardiff University – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- Imperial College London – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- London School of Economics (LSE) – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- Queen Mary University of London – 2009/10 to 2015/16

- University College London (UCL) – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Aberdeen – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Birmingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Bristol – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Edinburgh – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Nottingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Oxford – 2007/08 to 2016/17

- University of York – 2009/10 to 2016/17

- University of Manchester – 2008/09 to 2017/18

- University of Sheffield – 2006/07 to 2016/17

Note : The data used for this analysis was obtained from the above universities under the Freedom of Information Act. As per the Act, the information was provided in such a way that no specific individual can be identified from the data.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Advice for First-Year Ph.D. Students in Economics at Cornell

First of all: welcome to Cornell and congratulations on your acceptance into the Ph.D. program in Economics! You must wonder about what the program and life at Cornell will be like, both academically and socially. The main focus of this document is to provide some information, grad student to grad student, about the academic aspects of the Ph.D. program in Economics at Cornell, though we will also get into some other aspects of life at Cornell. From your peers in the Ph.D. program, we want you to know that we are happy to talk to you and give you advice based on our own experiences. The comments and advice have been gathered from a broad spectrum of students, with varying backgrounds and experiences. We hope that this will provide you with a number of perspectives and ideas on how to handle the first year and succeed to the best of your ability.

You Are Here for a Reason

The Cornell Ph.D. program in economics admits a wide variety of students, with various backgrounds and levels of academic preparation. By some system, the faculty sifts through literally hundreds of applications, to find a broad profile of students that best fit the research interests and teaching needs of the department. It should be no surprise that many of your classmates list labor, development, theory or econometrics as primary fields of interest – these are four of the areas in which Cornell Economics is strongest. The research done in each of these areas, as well as the other economics fields, requires fairly different skill sets, and therefore the students chosen for admission will vary in their preparation for the focus of the firstyear: learning quantitative tools, basic economic modeling frameworks, and mathematical problem solving. Some of your classmates may have seen some of the material before. Don't let this discourage you – with sufficient effort and perseverance, you are all capable of succeeding in the first year. In order for you to be admitted, someone took notice of your file and saw something they liked. Remember these facts in the many challenging and difficult days you will face in the coming year. The Department does not accept students unless it believes they are capable of successfully completing the program, and differences in preparation in September will seem smaller come June.

You are also hopefully here for another reason, namely because you have decided that this is what you want to do (this being quantitatively-oriented research). For that reason, you should make the best of the opportunities here. Work as hard as you can, but enjoy the process. Yes, it is tough at times, but tough things can be made more bearable when we really enjoy the stuff and believe it is important. For this reason also, take initiative for your course of studies.