- DOI: 10.16538/J.CNKI.FEM.20210122.101

- Corpus ID: 236762831

A Literature Review of Organizational Resilience

- Lisa Ping , Jiazhe Zhu

- Published 20 March 2021

- Business, Psychology

10 Citations

Building organizational resilience in the era of uncertainty: strategies and best practices, seeking the resilience of service firms: a strategic learning process based on digital platform capability, development and validation of a resilience scale for construction project organization, from darkest to finest hour: recovery strategies and organizational resilience in china’s hotel industry during the covid-19 pandemic, research on the corporate innovation resilience of china based on fgm(1,1) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis model, organizational resilience and transformational leadership for managing complex school systems, school middle leaders' transformational leadership and organizational resilience: the moderating role of academic emphasis, predicting organization performance changes: a sequential data-based framework, how does organizational resilience promote firm growth the mediating role of strategic change and managerial myopia, the double‐edged sword effect of organizational resilience on esg performance, 25 references, resilience in business and management research: a review of influential publications and a research agenda, bouncing back: building resilience through social and environmental practices in the context of the 2008 global financial crisis, the long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices, evolving conceptualizations of organizational environmentalism: a path generation account, legitimizing, leveraging, and launching: developing dynamic capabilities in the mne, cog in the wheel: resource release and the scope of interdependencies in corporate adjustment activities, ceo greed, corporate social responsibility, and organizational resilience to systemic shocks, caught in the crossfire: dimensions of vulnerability and foreign multinationals' exit from war-afflicted countries, group resilience: the place and meaning of relational pauses, organizing for resilience, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

REVIEW article

Building organizational resilience through organizational learning: a systematic review.

- 1 Department of Technology and Safety, UiT the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

- 2 Department of Leadership and Organisation, Kristiania University College, Oslo, Norway

With organizational environments becoming increasingly complex and volatile, the concept of “organizational resilience” has become the “new normal”. Organizational resilience is a complex and multidimensional concept which builds on the myriad of capabilities that an organization develops during its lifecycle. As learning is an inherent and essential part of these developments, it has become a central theme in literature on organizational resilience. Although organizational resilience and organizational learning are inherently interrelated, little is known of the dynamics of effective learning that may enhance organizational resilience. This study explores how to achieve organizational learning that can serve to promote organizational resilience. Our aim is to contribute to a more comprehensive knowledge of the relation between organizational resilience and organizational learning. We present the results of a systematic literature review to assess how organizational learning may make organizations more resilient. As both organizational resilience and organizational learning are topics of practical importance, our study offers a specifically targeted investigation of this relation. We examine the relevant literature on organizational learning and resilience, identifying core themes and the connection between the two concepts. Further, we provide a detailed description of data collection and analysis. Data were analyzed thematically using the qualitative research software NVivo. Our review covered 41 empirical, 12 conceptual and 6 literature review articles, all indicating learning as mainly linked to adaptation capabilities. However, we find that learning is connected to all three stages of resilience that organizations need to develop resilience: anticipation, coping, and adaptation. Effective learning depends upon appropriate management of experiential learning, on a systemic approach to learning, on the organizational ability to unlearn, and on the existence of the context that facilitates organizational learning.

Introduction

With organizational environments becoming more and more complex and volatile, the concept of “organizational resilience” (OR) has become increasingly significant for practice and research. OR is here understood as the organization's “ability to anticipate potential threats, to cope effectively with adverse events, and to adapt to changing conditions” ( Duchek, 2020 , p. 220). Thus, anticipation, coping, and adaptation represent three stages of OR. Further, the literature indicates that OR is an essential organizational meta-capability for the success of modern organizations ( Parsons, 2010 ; Näswall et al., 2013 ; Britt et al., 2016 ; Suryaningtyas et al., 2019 ). OR has indeed become the “new normal” ( Linnenluecke, 2017 ) regarding organizational survival as well as recovery and successful re-emergence after disruptions. Understanding OR is therefore more important than ever ( Ruiz-Martin et al., 2018 ). However, OR is still an emerging field ( Ma et al., 2018 )—and a key question that remains unanswered is how to achieve it ( Boin and Lodge, 2016 ; Chen R. et al., 2021 ).

Research is explicit on the complexity and multidimensional nature of OR: it is associated with an organization's capabilities to learn, adapt, and self-organize ( Linnenluecke and Griffiths, 2010 ), where learning is an inherent and essential element ( Boin and van Eeten, 2013 ). This links OR to learning processes (see, e.g., Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011 ; Rodríguez-Sánchez and Vera Perea, 2015 ), where learning has become a common theme in resilience literature. Khan et al. (2019 , p. 18) argue, “[o]rganizational learning capability is positively related to building and sustaining organizational resilience capability.” While OR is defined at the organizational level, the inherent learning is organizational learning (OL), understood as an “[ongoing] social process of individuals participating in situated practices that reproduce and expand organizational knowledge structures and link multiple levels of OL” ( Popova-Nowak and Cseh, 2015 , p. 318). Furthermore, research has noted the similarities between OR and OL ( Sitkin, 1992 ; Linnenluecke and Griffiths, 2010 ), as both require routines, values, models, and capabilities essential for organizations facing uncertainty. OR has also been defined as an outcome of organizational learning ( Sitkin, 1992 ; Sutcliffe and Vogus, 2003 ), suggesting that organizational learning capability may be enhanced by OR ( Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2021 ). However, OR is also a process ( Boin et al., 2010 ) that facilitates OL and feeds organizational self-development over time ( Lombardi et al., 2021 ). This makes OL both an important precondition for OR which relies on past learning, and an outcome of it that fosters future learning ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 ). OR and OL may therefore reinforce each other.

Although OR and OL are inherently interrelated, our understanding of the dynamics of effective learning is limited ( Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer, 2014 ), and further study is needed of the relationship between organizational learning and resilience ( Mousa et al., 2017 , 2020 ; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2021 ). Further research on learning connected to OR is needed to understand “the character of this learning and what specific resources give rise to it” ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 , p. 3421). Moreover, investigation is needed of what triggers learning and corresponding processes and exploring of the effective learning strategies that allow resilient organizations to avoid pathological learning cycles ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 ). Our aim with this study is therefore to contribute to more comprehensive knowledge on the relationship between OR and OL and to further explore the relationship between them by asking the research question: How to improve organizational learning to make organizations more resilient?

Theoretical Framework

OL assumes interaction of its multiple levels of analysis, including the individual, group, organizational, and inter-organizational levels ( Lundberg, 1995 ; Örtenblad, 2004 ; Popova-Nowak and Cseh, 2015 ). Being a social process, OL is embedded in everyday organizational practice when individuals acquire, produce, reproduce, and expand organizational knowledge ( Lave and Wenger, 1991 ; Gherardi et al., 1998 ; Gherardi and Nicolini, 2002 ; Gherardi, 2008 ; Chiva et al., 2014 ). This individual knowledge, either explicit or tacit ( Cook and Yanow, 1993 ), must become part of organizational repository that includes tools, routines, social networks and transactive memory systems ( Huber, 1991 , p. 89–90; Walsh and Ungson, 1991 ; Argote and Ingram, 2000 ; Argote, 2011 ). OL directly affects organizations facing turbulence ( Baker and Sinkula, 1999 ) and involves “the extraction of positive lessons from the negativity of life” ( Giustiniano et al., 2018 , p. 133) that are useful to the whole organization. OL will therefore directly affect how resilient organizational performance is ( Giustiniano et al., 2018 ).

Learning is emergent in nature ( Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer, 2014 ). As a continuous process, OL implies accomplishment of specific steps. However, what those steps are varies, though with certain overlaps, across the literature (see, e.g., Huber, 1991 ; Argyris and Schön, 1996 ; Crossan et al., 1999 ; Lawrence et al., 2005 ; Jones and Macpherson, 2006 ; Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ; Argote et al., 2020 ). Further, OL may vary in complexity and outcomes. At the lower (single-loop) level, OL results in detection and correction of errors “without questioning or altering the underlying values of the system” ( Argyris and Schön, 1978 , p. 8). At the higher (double-loop) level of learning, “errors are corrected by changing the governing values and then the actions” ( Argyris, 2002 , p. 206). Triple-loop learning (deutero-learning) enables organizations to learn about their own learning processes ( Argyris and Schön, 1978 , 1996 ). OL may be exploratory—associated with “search, variation, risk taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery and innovation” ( March, 1991 , p. 71), or exploitive—utilizing the “old certainties” ( March, 1991 , p. 71). The trade-off between the two is a key concern of studies of adaptive processes; organizations need to have an appropriate balance between these strategies ( Levinthal and March, 1993 ) to maintain “ambidexterity” ( Lavie et al., 2010 ). Importantly, OL is not necessarily always a conscious or intentional effort, neither does it imply behavioral change ( Hernes and Irgens, 2013 ) or always increase the learner's effectiveness (even potential effectiveness); finally, it does not always lead to true knowledge, as organizations “can incorrectly learn, and they can correctly learn that which is incorrect” ( Huber, 1991 , p. 89).

Organizations struggle to implement OL ( Lipshitz et al., 2002 ; Reich, 2007 ; Garvin et al., 2008 ; Taylor et al., 2010 ; Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer, 2014 ) due to a wide range of barriers (see, e.g., Schilling and Kluge, 2009 ). Productive OL is complex and relies on the interaction of various facets—cultural, psychological, policy, and contextual ( Lipshitz et al., 2002 ; see also Garvin, 1993 ). These interactions may produce differing configurations and will vary across organizations. Experience has a special role as a key prerequisite for OL, but experience is extremely diverse in nature ( Argote and Todorova, 2007 ; Argote, 2011 ; Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ) and its relevance is only partial ( Weick and Sutcliffe, 2015 ). In order for experience to be a “good teacher” ( March, 2010 ) organizations must understand its nature and how different types of experience interplay ( Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ). The relationship between the experience and learning processes and outcomes is moderated by context ( Argote, 2011 , p. 441). Effective OL relies on a suitable context ( Antonacopoulou and Chiva, 2007 , p. 289) that can be complex and multidimensional ( Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ): inter alia , external organizational environments, organizational culture, strategy and structure, power relationship within the organization and inter-organizational processes and interactions. The contextual components through which learning occurs are active, whereas others that shape the active context are latent (see Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 for details).

Thus, OR is founded on learning processes (assessment, sense making, distilling lessons learned and integration of new understandings into existing practice) that are embedded in organizational routines ( Powley and Cameron, 2020 ) that penetrate all stages of OR ( Duchek, 2020 ). Achieving OR requires commitment and studying this commitment implies an enquiry into organizational learning, knowledge, and capability development ( Weick and Sutcliffe, 2015 , p. 108). Research has noted that different types of resilience associate with different learning strategies: adaptive resilience has been associated with single-loop learning ( Lombardi et al., 2021 , p. 2). In contrast, reactive resilience refers to the ability to view disruptions as sources of learning and growth at various organizational levels, where organizations must adopt new practices based on their experience, resulting in a double-loop learning. Resilience also entails a process of deutero-learning or “learning to learn” ( Andersen, 2016 ), thus requiring a completely new experimentation approach. OR is enhanced when organizations build routines that can facilitate OL. The major challenge for an organization that aims at enabling resilience is to establish the right learning routines (see, e.g., Kayes, 2015 ): that is to say, those that achieve effective/productive OL.

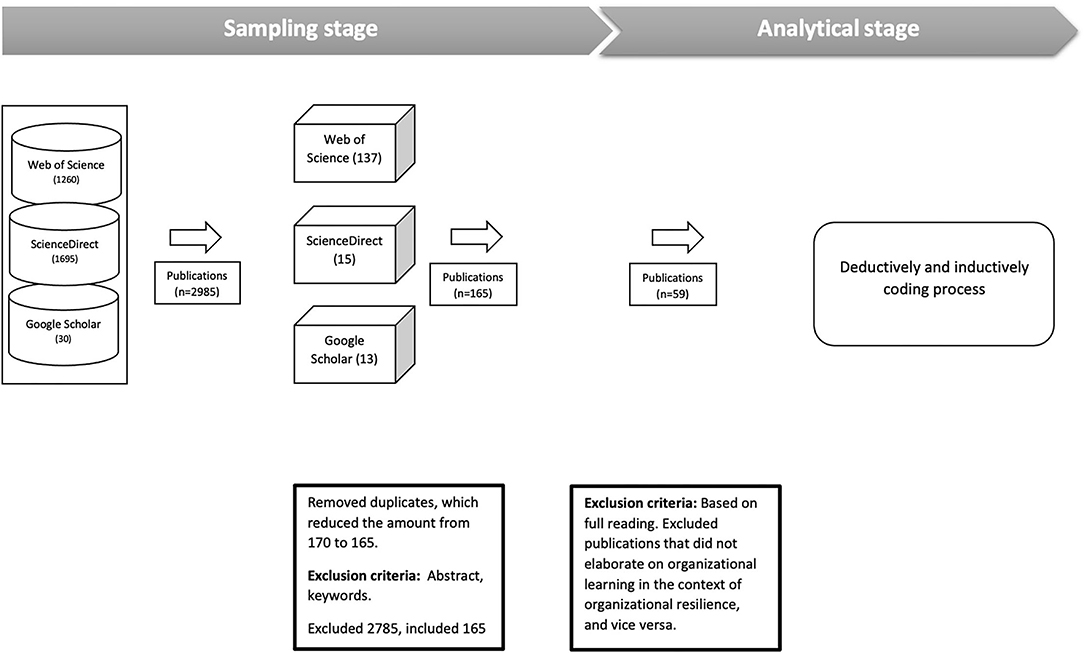

A systematic literature review (SLR) was chosen since it facilitates gathering of a wide range of relevant sources ( Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ) and ensures clarity of inclusion and exclusion criteria ( Mackay and Zundel, 2017 )—important when, as with OR, intellectual coherence or a standard theoretical framework is lacking ( Liñán and Fayolle, 2015 ). Our review was outcomes-oriented, aiming to identify “central issues” ( Cooper, 1988 , p. 109); relevant literature was retrieved through an exhaustive review with selective citation, to consider all relevant publications for the research question. SLR involves two stages: a sampling and an analytical stage ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Methodological steps for literature review (source: the authors).

Conducting the Review

The sampling stage.

Our initial search criteria were broad to include as many relevant results as possible. To obtain an overview of the available literature, the following databases were used: Science Direct, Web of Knowledge (Search in the core collection) and Google Scholar (for the latest publications and gray literature). 1 As Google Scholar is a compilation of records from other databases ( Kugley et al., 2017 ) several articles had already been identified by Science Direct and Web of knowledge. All databases are frequently used by researchers of various disciplines ( Xiao and Watson, 2019 ). The literature search was performed by the first author, in the period March–May 2021, covering publications between 1900 and 2021. A diary was made to keep record of the results, with search dates, search strings and results.

Search strings were developed by applying the keywords “organizational resilience” and “organizational learning”. In Web of Knowledge, the Boolean operator (AND) was applied together with truncation symbol of the asterisk to include all forms of the words [TS = (resilien * AND organi * AND learning)]. The same keywords were applied in Science Direct; as both UK and US spelling variants are supported, there was no need for truncation symbol. Google Scholar offers limited search terms options, and the selection is not as transparent as Web of Knowledge and Science Direct. However, we performed a search in Google Scholar to broaden the number of publications and ensure the latest articles from all fields and disciplines. Only the three first pages were included. The initial search performed by the first author yielded 2,985 articles. Next, the same author went through the abstracts and keywords. In cases where abstracts were not sufficiently informative, the article was read through quickly. Duplicates were removed, which reduced the number of articles from 170 to 165.

The following criteria were used in the screening process resulting in 2,985 publications:

Inclusion Criteria

1. Empirical, conceptual, and theoretically oriented publications about organizational learning within organizational resilience

2. Publications written in English

3. Article type (applied only in Science Direct): Review articles, research articles, book chapters, conference abstracts and data articles

4. Subject areas (only in Science Direct): Social sciences, environmental science, business, management and accounting, engineering

Exclusion Criteria

1. Non-academic journals

2. Publications not issued in English or Norwegian

3. Article type (only in Science Direct): encyclopedias, book reviews, case reports, conference info, correspondence, discussions, editorials, errata; examinations, mini-reviews, news, practice guidelines, short communications, software publications, other

4. Subject areas (only in Science Direct): medicine and dentistry, psychology, agricultural and biological sciences, computer science, energy, neuro-science

Analytical Stage

The articles were randomly distributed to the three authors for a full reading, so that each article could be sorted as follows: (1) How organizational learning contributes to organizational resilience; (2) How OR contributes to organizational learning; (3) Uncertain. Articles placed in the latter category were discussed and given an additional full reading by the first author before a decision on category placement, or exclusion was made. As a result of this analytical screening process, 59 articles were included in the final review. After the phases of thematic analysis ( Braun and Clarke, 2006 ) the articles were coded in NVivo 20 (Release 1.5). A deductive coding scheme was developed, based partly on Boyatzis (1998) approach. Theory on organizational learning informed the following deductive coding categories: experience; practices; strategies; effective learning; mechanisms; knowledge; processes and context. The Duchek (2020) conceptualization of resilience informed the codes: anticipation; coping; adaptation. The coding process started deductively; we inductively created additional codes underway. The first round of coding was performed by the first author and then presented to the co-authors. The second round of coding was performed by the first and second authors, and themes were created when we found “something important in relation to the overall research question” ( Braun and Clarke, 2006 , p. 83). Data were aggregated into clustered codes ( Miles and Huberman, 1994 ). A memo of the coding process was kept in NVivo. Analysis of our findings is presented below.

Literature Review

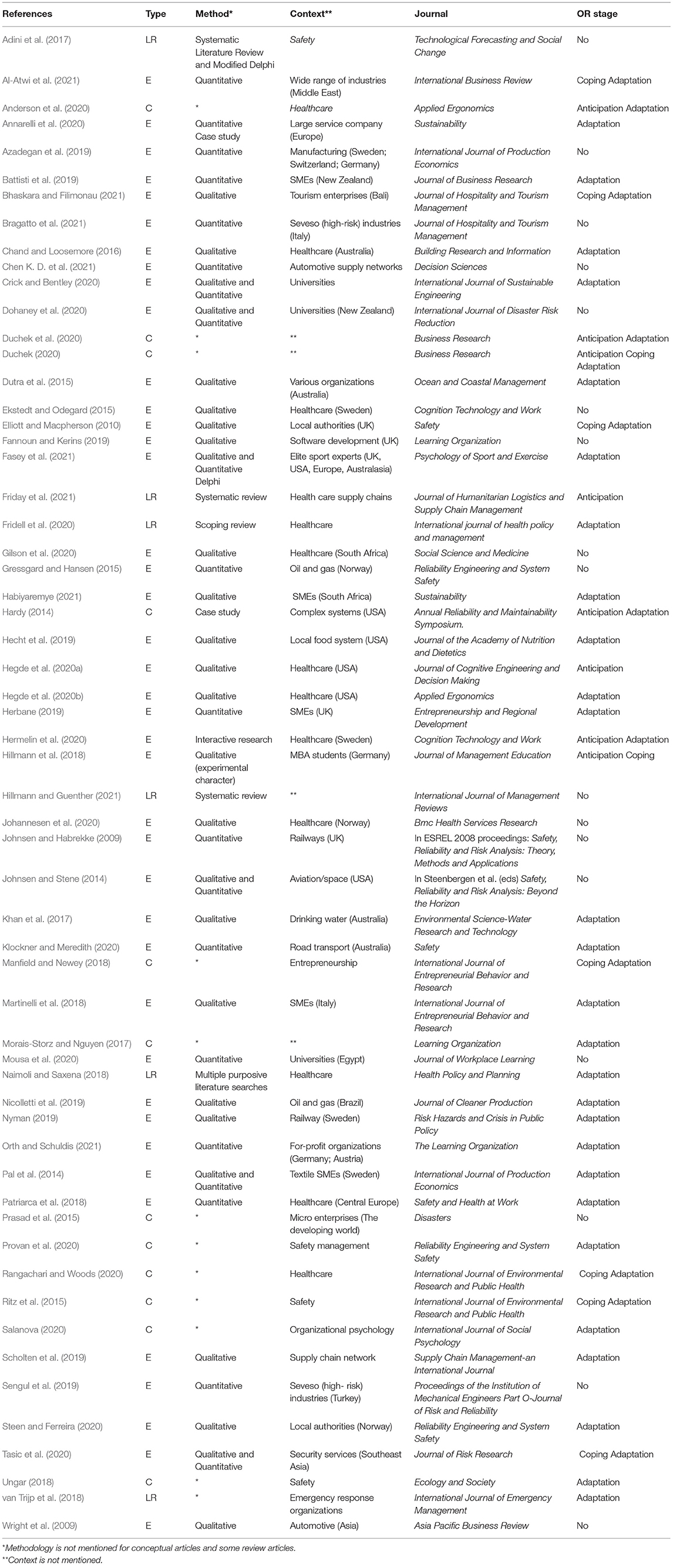

The literature on organizational resilience has expanded massively in recent years, developing from being highly conceptual to containing increasingly more empirical contributions. Our 59-article review is presented in Table 1 : 41 empirical, 12 conceptual and 6 literature-review articles. The empirical articles use various types of data from different contexts; 19 use qualitative data, 13 apply quantitative data and six mixed methods; further, healthcare (13), universities (4), SMEs (5) and transport (4) are the dominant contexts. The articles were published in 45 different journals, in addition to two book volumes and two conference/symposium proceedings; and no single journal dominates. The highest number of contributions within one journal was three, for Reliability Engineering & System Safety . The journals are located within many different fields, with business (11) predominant, followed by safety (7), learning (4) and healthcare (5). Regarding geographical context for the empirical studies, all continents are represented, with Europe dominant (19), followed by Australasia (6) and the USA (5).

Table 1 . Overview of articles and stage of organizational resilience for their organizational learning focus (Source: the authors).

Our review shows that learning is connected to resilience through the capabilities that organizations must possess and develop. Scholten et al. (2019) pointed out that “learning is ongoing across all stages of a disruption” (p. 439); we found that the same can be said about learning in the resilience stages. Our review shows that learning can prepare organizations for future events. Eight articles explicitly address learning as part of the anticipation capability . Overall, we see that anticipation refers to proactive action ( Hardy, 2014 ; Duchek, 2020 ) where organizations detect “emerging problems” ( Anderson et al., 2020 , p. 2), “anticipate what could happen in an actual event” ( Hermelin et al., 2020 , p. 670) and then act on this. Adding experience to the organization's knowledge base is crucial, influencing how successful the organizational ability to anticipate further needs will be. Anticipation is dependent on the organizational ability to learn ( Hillmann et al., 2018 ), which “guides and supports” ( Ritz et al., 2015 , p. 1868) advancement to the next stage of the resilience process: coping. Moreover, learning developed during this stage will inevitably influence capabilities developed in the two other stages ( Anderson et al., 2020 ), and further improve organizational response. Nine articles explicitly address learning as part of capabilities to cope with uncertainty and sudden changes ( Al-Atwi et al., 2021 ). We noted a tendency to address the role of learning in coping as a chance for organizations to expand their cognitive and behavioral perspectives ( Tasic et al., 2020 ) and thus broaden the range of actions ( Duchek, 2020 ) to build resilience to offer “better future protection” ( Manfield and Newey, 2018 , p. 1161). However, our study shows that the literature on OR learning is overwhelmingly concerned with adaptation capabilities. Altogether 38 articles explicitly include learning as part of adaptation , which could be explained by the fact that “adaptation may be what truly defines resilience” ( Hardy, 2014 ). Learning is central to the adaptive capacity of an organization ( Orth and Schuldis, 2021 ) and adaptability is held to be closely related to organizational learning ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ). Organizations must continuously absorb information and adapt to changes in the environment, in turn building on continuous learning ( Battisti et al., 2019 ). Similarly, Crick and Bentley (2020) state that the interaction between absorbing information and the environment that can lead to adaptation is driven by learning; while Dutra et al. (2015) argue that adaptation occurs through learning and transmission of knowledge. In the context of developing organizational resilience, adaptation means more than simply getting the organization back to normal—it also involves developing capabilities to change and learn ( Scholten et al., 2019 ; Duchek et al., 2020 ). As shown by Bragatto et al. (2021) , building resilience involves more than just adapting disaster management plans: it also entails understanding and managing people's behavioral norms and mental models to help them unlearn behaviors which might have led to failure in the first place.

Analysis of Findings

Our findings affirm and strengthen the link between Organizational Learning (OL) and Organizational Resilience (OR). Whereas, Pal et al. (2014) found that learning increased resilient performance, Nyman (2019) argued that learning is a “precondition for resilience”. Mousa et al. (2020) have showed the role that organizational learning plays in predicting OR, while others, like Bhaskara and Filimonau (2021) , highlight this relationship by arguing that limited organizational learning is a disadvantage for developing resilience: it is important to “aim at facilitating organizational learning” (p. 373). Our findings highlight the importance of identifying the determinants of OL in order to improve OR ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ); further, that resilience can be learned and therefore deliberately built ( Manfield and Newey, 2018 ; Salanova, 2020 ). The identified main elements of OL for improving OR are appropriate management of experiential learning, a systemic approach to learning, the organizational ability to unlearn, and the existence of the context that facilitates organizational learning.

Learning From Experience

The importance of experiential learning has been heavily stressed in the OR literature ( Hecht et al., 2019 ; Bragatto et al., 2021 ; Habiyaremye, 2021 ). Chand and Loosemore (2016) point out that such experience can be acquired during real events, training exercises and drills. Several authors address the important role of training and exercises (e.g., Chand and Loosemore, 2016 ; Adini et al., 2017 ; Khan et al., 2017 ; Hecht et al., 2019 ; Hermelin et al., 2020 ; Tasic et al., 2020 ; Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ), including the post-exercise debriefing session as learning-promoting activities that will enhance OR. Moreover, OR may be improved by experience and learning from accidents, with a focus on clear communication and common training to share experiences from “accidents, fatalities and good practices” ( Johnsen and Habrekke, 2009 , p. 8). Both positive and negative learning from own experiences is crucial for showing how to increase positive outcomes and avoid negative ones ( Anderson et al., 2020 ). Learning from failures is among the key capabilities of a resilient organization ( Herbane, 2019 ; Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ); further, some (e.g., Madsen and Desai, 2010 , cited by Manfield and Newey, 2018 ) have argued that organizations can learn more from failure than success, particularly on the case of major failures. There are also important lessons to be learned from successes ( Hardy, 2014 ; Hermelin et al., 2020 ) and from reflecting on positive outcomes. Scholten et al. (2019 , p. 438) point out that organizations that do not “reflect on positive outcomes might inhibit organizations in seizing all the benefits of intentional experiential learning.”

However, past experiences may provide limited learning opportunities ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ). Although experience can enable organizations to replay what has been previously learned, they may fail “to prepare […] for unforeseen and unpredicted events” ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 16). Established “best practices” may not be suitable for other crisis situations ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 16) and knowledge gained from one context cannot always be readily transferred to a different context: “coping with crisis cannot just be about deliberately acquiring a set of transmitted abilities, since to achieve competent practice depends on becoming better by doing” ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 6). The diverse nature of some events may also impede effective OL ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ). Past experiences may be codified into standard practices with “step-by-step” guidelines and operating procedures. However, such “codified learning” is problematic, as “the actual practice evolves as those in charge or involved in circumstances make sense of the ambiguous information, confused circumstances and incomplete data with which they are faced” ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 10). Therefore, codified learning can “only ever be partially successful” ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 11).

Another finding is the importance of how experience is dealt with . To ensure a true learning experience, acquired knowledge should be applied to real situations ( Hillmann et al., 2018 ). Assuming that resilience is built through a combination of specific theoretical input and experiential learning, a combination will positively influence e.g., long-term learning and “thinking in complexity through imagining different futures” ( Hillmann et al., 2018 , p. 481). For example, extreme weather events have been found to “provide the best opportunities for experiential learning about how to improve hospital resilience to such events” and “embedding such experiences into hospital disaster management planning processes” ( Chand and Loosemore, 2016 , p. 885). Although crisis events have been subjected to extensive investigation, it is evident that organizations often fail to learn effectively, even when crises are regular events ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ). One contributing factor for this failure may be the fragmented nature of our understanding, and the resulting piecemeal conceptualization of the learning process ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 ). For example, a disturbance may be familiar to the organization; but, due to bounded rationality, the need for new learning is not always identified, as organizations will often choose to fall back on old practices instead of developing new ones ( Manfield and Newey, 2018 ). This results in lowered reintegration and internationalization of learning and reduced organizational resilience that stops being a growth experience ( Manfield and Newey, 2018 ). Moreover, time lag and spatial distance may challenge the opportunity to learn from experience with a specific situation ( Anderson et al., 2020 ). Therefore, improved organizational learning must involve better understanding of the causes of accidents ( Johnsen and Habrekke, 2009 ), with a focus on triple-loop learning ( Bragatto et al., 2021 ). It is not sufficient merely to collect reports of problems: organizations need to ensure that the reports are studied, and corrective actions implemented ( Hardy, 2014 ). Another cause of unsuccessful OL is in confusing learning with identifying lessons ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 ): “organizations often generate new knowledge (lessons learned) but fail to translate this knowledge into new behaviors” ( Duchek, 2020 , p. 231). It is important to recognize that lessons have not been learned until they are successfully implemented ( Chand and Loosemore, 2016 ; Duchek, 2020 ).

Several authors highlight the value of organizations learning from the practices and experiences of other organizations ( Gressgard and Hansen, 2015 ; Johannesen et al., 2020 ; Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ; Fasey et al., 2021 ; Friday et al., 2021 ; Habiyaremye, 2021 as central to OL ( Khan et al., 2017 ; Herbane, 2019 ). This may also spread further, to a whole network, as suppliers interact with each other, thereby also facilitating network resilience ( Chen K. D. et al., 2021 ). Effective learning involves critical reflection at several levels, with effective communication and information sharing among the involved actors throughout the system ( Johnsen and Habrekke, 2009 ; Dutra et al., 2015 ; Nicolletti et al., 2019 ). Such collaboration should “not only capture lessons learnt but also allow effective use and sharing of information across the multiple stakeholders involved in disaster planning” ( Chand and Loosemore, 2016 , p. 885). Our findings highlight the importance of a holistic approach to understanding this collective learning process among the many stakeholders involved in a disaster response ( Bragatto et al., 2021 ). Lack of appropriate collaboration with other relevant stakeholders inhibits OL by depriving organizations of valuable opportunities to learn from others ( Johnsen and Habrekke, 2009 ; Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ). Moreover, learning from others may be inhibited by differing “resources, objectives and variations in learning experiences” between organizations ( Friday et al., 2021 , p. 262).

Importance of Continuity and Need for a System

Building resilience requires capturing and embodiment of learning into a capability ( Hillmann et al., 2018 ). This in turn implies learning from adversity and codifying this learning into resilience capabilities against specific threats, thereby offering better future protection ( Folke et al., 2004 , cited by Manfield and Newey, 2018 ). Findings also demonstrate the importance of having systems in place for organizational learning to happen , and remaining continuous. Such systems must incorporate a range of learning practices that will ensure better reflection of experienced crises and as an outcome a more effective learning ( Duchek et al., 2020 ). Organizations learn “in, from and for crisis” ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 3). To enhance OR, learning has to be ongoing ( Chand and Loosemore, 2016 ; Bragatto et al., 2021 ), running across “the continuum of situations” from everyday practice to action during critical events ( Hegde et al., 2020a , p. 75). Our findings emphasize that a resilient system continually learns, improves, and adjusts, even when stressed, and improves after a disturbance through adaptation (see also Hardy, 2014 ; Martinelli et al., 2018 ). In contrast to the results of other studies on learning from near misses , Azadegan et al. (2019) found that organizations “do learn significantly from such events” (p. 224). Further, when organizations experience near-misses, they consider long-term issues by “implementing procedural response strategies” ( Azadegan et al., 2019 , p. 221), such as formal protocols, policies, and procedures, in contrast to theoretical suggestions that often indicate consideration of flexible strategies. Such procedural strategies are in line with double-loop learning, whereas flexible strategies are more in line with single-loop learning ( Azadegan et al., 2019 ). Moreover, learning from accidents, or even more extreme events such as emergencies and catastrophes, needs to be integrated with learning from minor consequence events or even from the normal functioning of everyday activities ( Hollnagel, 2011 , cited by Patriarca et al., 2018 , p. 267). The literature reviewed highlights how resilient learning is “ambidextrous,” with a diversity of practices that organizations should explore and exploit ( Al-Atwi et al., 2021 ), balancing flexible and procedural strategies ( Azadegan et al., 2019 ).

Our findings also reveal emphasis on the knowledge base , and how knowledge is managed within the organization (see Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 ; Nicolletti et al., 2019 ; Anderson et al., 2020 ; Duchek, 2020 ; Duchek et al., 2020 ; Steen and Ferreira, 2020 ; Habiyaremye, 2021 ). Knowledge is generated through the stages of resilience—in other words, from the crisis event context that can create the need for change. Some authors hold that the organizational reaction to change is expressed by adaptation ( Naimoli and Saxena, 2018 ; Fridell et al., 2020 ) so organizations must develop their capacity for change, which is predicated on the capacity for continuous learning ( Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ). Adaptive learning is crucial to the ability to bounce back from adverse events that underlie crises ( Habiyaremye, 2021 ). Therefore, we hold that learning is a mechanism for change which is needed in developing organizational resilience in the face of new problems ( Anderson et al., 2020 ; Steen and Ferreira, 2020 ; Fasey et al., 2021 ). Knowledge, as the key antecedent of OR ( Duchek, 2020 ), is also fundamental for resilient system performance irrespective of the activity in focus ( Adini et al., 2017 ). It is, however, important to distinguish among sources of knowledge, as different sources are associated with different performance outcomes ( Battisti et al., 2019 ).

To develop resilience, knowledge must remain in the organization, as employees may come and go ( Dohaney et al., 2020 ). That being said, improved OL relies on the feedback process where individual lessons are shared collectively ( Chand and Loosemore, 2016 ). Gressgard and Hansen (2015) argue that, for learning to contribute to building resilience, diversity of opinions and perspectives is important . Further, that knowledge exchange between and across units in the organization increases the ability to learn from failure, as compared to knowledge exchange within units. This highlights the need to improve the feedback process ( Bragatto et al., 2021 ) and develop an appropriate system for knowledge-sharing from the individual to the organizational level ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 ), relying on various practices (see e.g., Khan et al., 2017 ; Martinelli et al., 2018 ; Hegde et al., 2020a ; Habiyaremye, 2021 ). This system should be based on trust and inclusion, to ensure efficient and appropriate communication ( Rangachari and Woods, 2020 ). Moreover, organizations should develop processes and structures to utilize knowledge and implement this knowledge into future responses ( Chand and Loosemore, 2016 ). In the absence of such systems, OR will remain “reactive (brittle) and restricted to the frontlines, with no way of advancing to team and organizational levels” ( Rangachari and Woods, 2020 , p. 6).

Dimensions of Learning Practices

Our findings also show that organizational learning is established through both formal and informal practices (see Gressgard and Hansen, 2015 ; Hecht et al., 2019 ; Hermelin et al., 2020 ; Orth and Schuldis, 2021 )—and that formal practices are particularly associated with learning from failure ( Hardy, 2014 ). Some studies find that formal practices ensure more thorough transfer of information, highlighting that disruption may undermine informal systems for knowledge exchange ( Orth and Schuldis, 2021 ). Yet, our findings underscore the important role of informal practices—indicating that earlier analyses have been overly focused on formal rules and policies, and that new insights might emerge through a fuller examination of how informal organizational rules, norms and practices work ( Bragatto et al., 2021 ). Finally, Chand and Loosemore (2016) note that informal organizational rules, norms, and practices may “undermine formal rules in determining... resilience” (p. 886).

With regard to the dimensions of learning, the literature reviewed for this study also focuses on investigating how lessons are learned and transferred among the various stakeholders ( Bragatto et al., 2021 ) by examining the specific learning mechanisms that lead to differing resilient performance effects over time ( Battisti et al., 2019 ). Taking as a starting point that learning is ongoing across all stages of a disruption [preparation (anticipation), response (coping) and recovery (adaptation)], Scholten et al. (2019) uncover six specific learning mechanisms and their nine antecedents for building supply-chain resilience. They place these mechanisms in two large categories associated with learning: intentional and unintentional. Intentional mechanisms are anticipative, situational, and vicarious learning. Anticipative learning takes place in anticipation of possible disruptions, aiming at knowledge transfer through formal training, education and collaboration; it results in the establishment of new routines or improvement of existing ones. Situational learning occurs during the coping stage, in the moment of disruption when organizations need to target the challenges that could have been anticipated but were not. Vicarious learning occurs during the adaption stage; it involves knowledge transfer based on the experiences and reflections of others. Unintentional learning mechanisms are processual, collaborative, and experiential learning. Processual learning occurs because of the proactive knowledge creation deduced from inherent organizational processes (e.g., changes in strategy, organizational growth, and operational refinement). Collaborative learning may occur during the response phase of disruption, when an immediate solution is needed, but procedures are lacking. Such instances may trigger collaboration and knowledge transfer across the actors involved. Experiential learning is associated with the recovery phase of disruption; it occurs through transfer of knowledge. Improved future performance relies heavily on rigorous and thorough learning from experience ( Ellis and Shpielberg, 2003 , cited by Scholten et al., 2019 )—as highlighted above. The trap of retrospective simplification of experience ( Christianson et al., 2009 , cited by Scholten et al., 2019 ) can be avoided by focusing on interpreting experience ( Levinthal and March, 1993 , cited by Scholten et al., 2019 ) instead of simplifying it. Finally, Scholten et al. (2019) highlight the largely overlooked value of unintentional learning.

The Role of Unlearning

OL is a cyclical process consisting of unlearning and learning , the “metamorphosis cycle” that is central to strategic resilience ( Starbuck, 1967 p. 113, cited by Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 , p. 4). The deliberate process of unlearning can be approached as a stand-alone process ( Fiol and O'Connor, 2017 ; Grisold et al., 2020 ), but it is a constituent component of this cycle ( Tsang and Zahra, 2008 , cited by Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ). The importance of unlearning has received particular attention in the literature on OR ( Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ; Orth and Schuldis, 2021 ). Unlearning is associated with “a process of getting rid of certain things from an organization” ( Tsang and Zahra, 2008 , p. 1437), often triggered by crisis ( Fiol and O'Connor, 2017 ) that requires organizations to adopt new ways of thinking and abandon old mental models and processes ( Duchek, 2020 ). In a world of turbulence and uncertainty, organizations are expected to act proactively, before action is desperately needed, through their own continual transformation ( Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ). Organizations must be able to identify the early warning signs of when action is needed, as shown through a “web of symptoms” ( Baer et al., 2013 , p. 199; Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ). Ideally, new learning should be created before the need for change has become desperately obvious ( Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ).

Learning and unlearning are mutually supportive in creating knowledge and organizational learning ( Morais-Storz and Nguyen, 2017 ). The most important role of unlearning is to clear away obstacles created from misleading knowledge and obsolete routines, so as to pave the way for future learning, but unlearning can also aid the effective acquisition of new understandings ( Fiol and O'Connor, 2017 ; Grisold et al., 2020 ). For most organizations, learning is impossible without unlearning: it is in fact the precondition for new learning, enhancing the effectiveness of learning in a process of change. It has been proposed that the greater the capacity for unlearning capability, the stronger may the positive effect of OL on OR be ( Orth and Schuldis, 2021 ). The metamorphosis cycle is driven by these two processes, organizational unlearning capability exerting a positive moderating effect on the relationship between organizational learning and organizational resilience ( Orth and Schuldis, 2021 ).

Context for Learning

Our review findings underscore the importance of context, to share and “capture the relevant information and to create a social learning process” ( Prasad et al., 2015 , p. 454) where individuals are committed and motivated to learn, to achieve improved OL ( Gilson et al., 2020 ). The main function of this context, necessary within and between organizations, is to support OL ( Naimoli and Saxena, 2018 ). While organizations learn from their own activities as well as from other organizations activities, there is also a question of different contexts for learning different knowledge. Given the nature and demands of adversity, the context also needs to be active— “not necessarily fully controlled and sequential, but instead open to innovative ways of tackling open problems” ( Hermelin et al., 2020 , p. 670).

Reflecting on the complexity of context (see Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ) our review has identified some contextual components that affect learning. Central here is the role of leadership. Attentive leadership and the wellbeing of employees is seen as “the core of learning and culture” ( Pal et al., 2014 , p. 418). “Listening, being respectful, allowing others to lead and creating spaces for learning from experience are important practices of leadership in complexity and for resilience” ( Belrhiti et al., 2018 ; Petrie and Swanson, 2018 , cited by Gilson et al., 2020 , p. 9). Associated with leadership are empowerment and role clarity that enable the extraction, distribution, and application of information “from failures made in various parts of the organizational system;” they are important to knowledge-exchange and are thus related to creating a context for learning from failure ( Gressgard and Hansen, 2015 , p. 173). Further, organizations need to be able to take in new information and reflect on experiences, in order to cope and adapt to situations of adversity ( Orth and Schuldis, 2021 ). Aspiring to learn and improve entails organizational desire to accept risk and failure, as both are inherent precursors of OL ( Fasey et al., 2021 ). Such exchange can be facilitated though enhanced work engagement and an open collaborative work climate ( Fasey et al., 2021 ). This in turn relies on leadership involvement and requires a more organic structure; where employees feel “responsible for the organization's development, they are more likely open to change” ( Duchek, 2020 , p. 237).

The findings indicate that organizational resistance to change has been noted as the main impediment to organizational transformation, and consequently to successful learning ( Hardy, 2014 ). Such resistance can be found in individuals and in organizations ( Donahue and Tuohy, 2006 , cited by Hardy, 2014 ). Within organizations, “ change fatigue” and lack of employee motivation may inhibit learning ( Manfield and Newey, 2018 , p. 1171). Motivation for learning is important ( Gilson et al., 2020 ), but so are other aspects like policy and administrative demands, often in combination with resource constraints ( Naimoli and Saxena, 2018 ) and the cost of studying reports and implementing actions ( Hardy, 2014 ). Learning from other organizations may be inhibited by “resources, objectives and variations in learning experiences” between organizations ( Friday et al., 2021 , p. 262).

Summary of the Analysis

In sum, our findings indicate that OL is essential to OR. However, the role of learning varies, depending on which stage of the resilience process is in focus. The frequent use of learning in relation to adaptation as opposed to anticipation and coping shows that learning is especially important in this resilience stage. However, as Table 1 shows, learning is also addressed in the two latter stages; and, as underlined by several authors, it is a central part of overall resilience. Resilience can be built by improving the effectiveness of learning. Our results indicate that experiential learning is central to how organizations gain and expand knowledge in order to improve their capabilities. Effective OL relies on a system to ensure its continuity, knowledge-transfer across organizational levels, with organizational processes that allow for formal as well as informal practices. Our review has also shown that unlearning is necessary to facilitate and adopt new and updated learning, thereby ensuring further growth toward OR. Finally, effective learning requires a supportive context.

Our review shows that OR is becoming an important goal for various types of organizations regarding crisis management, but most of all, improved performance in a world of high uncertainty. The dominance of qualitative data may be interpreted as a sign of this being a relatively young field of research. Further, it seems reasonable for empirical studies from high-risk industries like healthcare and transport dominate the field. Interestingly, however, also other fields, like tourism, food, retail, public administration and universities, also are represented as empirical fields. We interpret this as a sign of the growing interest in improving organizational performance under conditions of adversity in all branches and sectors because of the increased global threat picture. The representation of all continents as geographical contexts, and the high number of recent articles (46 out of 59 published the between 2017 and 2021) shows the growing interest in the connection between OR and OL as an emerging field of research worldwide.

Despite some variation in how explicit the studies examined here are in their use of terminology, our review clearly shows the fundamental role of OL in building OR. Some articles specify and highlight learning in connection to anticipation, coping or adaptation; others do not. Regardless, learning is still implicitly present and arguably crucial for improving performance and developing OR. Yet, the literature on resilience would stand to benefit from addressing learning more directl y, rather than as implicit, or in “broad terms only” ( Battisti et al., 2019 , p. 39). In this study, we have focused on the capabilities underlying the above mentioned stages of resilience—specifically on learning as a means for building them. Our findings show that adaptation is recognized as vital for resilience, but that goes for learning as well, as it facilitates the development of the other resilience stages and capabilities. Just as OL relies on multiple levels of interactions within and outside an organization so does OR. The frequent use of learning in relation to the adaptation stage, in comparison to the anticipation and coping stages, shows that learning is especially important in this stage of OR.

From our findings on how learning is addressed in the literature on resilience, we argue that the dynamic nature of learning in resilience is particularly evident in the conceptualizations of coping. Organizations learn “in, from and for crisis” ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 , p. 3) and cope by using past experience (both positive and negative) and knowledge to manage current situations. The interaction between coping and the two other stages of resilience can be said to be strongly driven by learning. In turn, this implies that the capabilities that belong to other stages will be strengthened simultaneously. We hold that organizations can build resilience by focusing on improving their ability to learn. We find it reasonable to suggest that it may be advantageous for organizations to focus on their learning processes in daily organizational life, not only during disturbances and crisis events, if they wish to strengthen resilience.

Our review indicates that learning deserves greater emphasis in relation to how organizations can develop resilience . It also highlights the importance of identifying the determinants of OL in order to build OR. By elaborating the various facets of OL in OR, the value of informal and unintentional learning processes, the need for a system, contextual factors, and the focus on unlearning, our findings and analysis contribute with deeper insights to this field of study also reflecting on the complexity of OL interactions stated in theory. OR is indeed enhanced by facilitating OL, but many aspects influence how effective that learning will be. In practice this implies that organizations may improve learning by first identifying where there is a need for changing their practices and routines.

This study has affirmed and further nuanced OL as intentional and unintentional processes highlighting of the overlooked value of unintentional learning in particular. Effective OL is a matter of transforming relevant knowledge into practice including the transformation of “unintentional learning into explicit learning” ( Scholten et al., 2019 , p. 439). However, unintentional learning might, in fact, require more from the organization in terms of flexibility and attentiveness, to be able to recognize the learning opportunities that can improve performance and create appropriate systems for knowledge transfer. These intentional and unintentional learning processes are closely linked to the discussion of formal and informal learning practices. Practices that focus heavily on formal rules and learning policies are criticized, and the value of analyzing informal organizational rules, norms and practices is highlighted. Recognition of the importance of unlearning is an aspect of the connection between OL and OR that was not included in our theoretical framework. This constitutes one of the most important contributions of our study. Unlearning in developing OR involves abandoning old mental constructs in favor of new, more relevant ones—which in turn implies that organizations must identify which of their current practices and routines obstruct growth, to pave the way for necessary changes. Our findings show that double-loop and triple-loop learning are especially crucial for developing OR. This deeper learning is necessary to avoid pitfalls that hinder effective learning. Further, improved OL depends on a better understanding of root causes of events, with consideration given to long-term issues as opposed to correcting errors. We also found that focusing on learning processes (triple-loop learning), by establishing processes and routines appropriate for learning specific, relevant lessons can foster the development of OR.

We argue that effective learning is facilitated through a learning system that captures the diverse nature of learning practices that are both flexible but also embedded in organizational routines relying on formal protocols, policies, and procedures. A main finding is that such a system is critical for developing OR because learning must be transformed into resilience capabilities. Moreover, a system for effective learning must facilitate communication and allow knowledge, experiences, opinions, and perspectives to be shared, both within and across organizations and stakeholders. We point out that collective inter-organizational learning is central to OR.

Limitations

One limitation of this article concerns the risk of failing to identify relevant contributions during the sampling stage and/or excluding some during the analytical screening process. Moreover, several important contributions have been published after May 2021. The amount of data in the 59 selected articles is huge and the scope of this article limited, so several interesting findings have had to be omitted. Thus, our selection of what to include constitutes another limitation. There is a further risk of missing something, or misinterpreting the findings, during the analytical cycles of the coding process. There exist various OR frameworks; we have chosen the one proposed by Duchek (2020) , but it might be that other frameworks would address OL differently. Learning is truly an inherent part of OR; and, as our focus has been on learning as part of resilience, we have not delved into the various frameworks for OR. We acknowledge the variations of terms and concepts employed to conceptualize resilience, such as monitoring and responding ( Adini et al., 2017 ; Anderson et al., 2020 ), but here we have emphasized what the terms and concept capture and express in terms of learning . We have not addressed the complexity of OL, which, however, should be clear from our data on aspects of unlearning and intended/unintended learning. Finally, we recognize the synergy between OR and OL ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 ; Lombardi et al., 2021 ; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2021 ) the scope of this article has been limited to how OL influences OR; the reverse effect has remained unexplored.

To our knowledge this is the first review to focus solely on the relationship between organizational learning and resilience, a relationship that has been discussed and established by scholars from various fields. More work is needed on how organizations can improve their learning abilities, as learning is essential for organizations to evolve from one resilience stage to another. OR can indeed be learned, so effective learning can serve as a critical driver for building OR. The effectiveness of OL can be increased by a more comprehensive understanding of the link between experiences and improved performance, with more focus on the value of diversity. OR is dependent upon an appropriate system to ensure continuous, inclusive, purposeful OL, capable of facilitating intentional and unintentional learning, and supported by an active context that enables new knowledge to enter the picture. Effective OL toward OR also requires the ability to unlearn previous ways of doing things, to learn and engage in new and improved ways of response. Lastly, organizations do not exist in a vacuum. OL must involve collaboration between organizations, to ensure sharing and exchange of valuable knowledge and experience, to build OR.

This article has theoretical and practical implications. As regards theory, our study contributes with insights on why learning is so central to resilience, through all the stages of capability. Our findings shed light on how learning can be targeted more effectively and how it can facilitate resilience. Second, our work shows the role of unlearning in OR, a point that deserves more attention in further research. In terms of theory, this study offers further insights into aspects of learning from experience and how this should be managed to build resilient organizations. On a practical note, there is still a need for empirical verification of the effects of learning on OR. More understanding is also needed of how learning interacts over time with other multilevel processes that contribute to building OR. Our findings have made clear the importance of establishing a system where organizations can build on the experiences and knowledge of other organizations in building resilience.

Our review also reveals need for further research . Current understanding of the dynamics of effective learning is at a very early stage, so more investment in systematic research on learning in organizations and their link to resilience-building ( Naimoli and Saxena, 2018 ) is called for. Further, there is a need for better understanding the correlation, if any, between disastrous events, their driving hazards, and major consequences; how learning occurs in affected organizations, and how long this organizational learning lasts ( Bhaskara and Filimonau, 2021 , p. 366). A key gap involves the scant attention given to the processes of knowledge transfer ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 ). Also needed is a deeper understanding of how learning interacts over time with other multilevel processes that contribute to building OR ( Fasey et al., 2021 ). Since learning is central if organizations are to evolve from one resilience stage to another, this review reveals the need for more research on how organizations can improve their learning abilities in general. More research, preferably empirical, is needed on the role, and potential, of informal practices and unintentional learning processes to improve OL related to OR, and on the role and practices of unlearning. Our study has also revealed the need for more research on the link between OL and learning at the individual, group and interorganizational levels. Even if it may seem paradoxical to “organize” for informal and unintended processes, this links in with the need for continuity and a coherent learning system.

Author Contributions

LE and MS conceptualized the article and coded and analyzed the material. MS provided the analytical framework. LE performed the data sampling, organized the material, and performed the first round of coding. AG provided Table 1 and contributed with critical editing of the whole manuscript. All authors contributed in the screening process, analytical stage with writing and critical editing, and have approved the submitted text.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ “Grey literature stands for manifold document types produced on all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats that are protected by intellectual property rights, of sufficient quality to be collected and preserved by library holdings or institutional repositories, but not controlled by commercial publishers, i.e., where publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body” ( Schöpfel, 2010 ).

Adini, B., Cohen, O., Eide, A. W., Nilsson, S., Aharonson-Daniel, L., and Herrera, I. A. (2017). Striving to be resilient: what concepts, approaches and practices should be incorporated in resilience management guidelines? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 121, 39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.01.020

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Al-Atwi, A. A., Amankwah-Amoah, J., and Khan, Z. (2021). Micro-foundations of organizational design and sustainability: the mediating role of learning ambidexterity. Int. Bus. Rev. 30, 11. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101656

Andersen, E. (2016). Learning to learn. Harvard Buisness Review , 94. Available online at: https://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/R1603J-PDF-ENG (accessed December 12, 2021).

Anderson, J. E., Ross, A. J., Macrae, C., and Wiig, S. (2020). Defining adaptive capacity in healthcare: a new framework for researching resilient performance. Appl. Ergon. 87, 9. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103111

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Annarelli, A., Battistella, C., and Nonino, F. (2020). A Framework to evaluate the effects of organizational resilience on service quality. Sustainability 12, 958. doi: 10.3390/su12030958

Antonacopoulou, E., and Chiva, R. (2007). The social complexity of organizational learning: the dynamics of learning and organizing. Manage. Learn. 38, 277–295. doi: 10.1177/1350507607079029

Antonacopoulou, E. P., and Sheaffer, Z. (2014). Learning in crisis:rethinking the relationship between organizational learning and crisis management. J. Manage. Inquiry 23, 5–21. doi: 10.1177/1056492612472730

Argote, L. (2011). Organizational learning research: past, present and future. Manage. Learn. 42, 439–446. doi: 10.1177/1350507611408217

Argote, L., and Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: a basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 82, 150–169. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2000.2893

Argote, L., Lee, S., and Park, J. (2020). Organizational learning processes and outcomes: major findings and future research directions. Manage. Sci. 67, 5399–5429. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2020.3693

Argote, L., and Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organizational learning: from experience to knowledge. Organization Sci. 22, 1123–1137. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0621

Argote, L., and Todorova, G. (2007). “Organizational learning: review and future directions,” in International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology , editors G. P. Hodgkinson and J. K. Ford (New York, Ny: John Wiley & Sons Ltd), 193–234.

Google Scholar

Argyris, C. (2002). Double-loop learning, teaching, and research. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 1, 206–218. doi: 10.5465/amle.2002.8509400

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1996). Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Azadegan, A., Srinivasan, R., Blome, C., and Tajeddini, K. (2019). Learning from near-miss events: an organizational learning perspective on supply chain disruption response. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 216, 215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.04.021

Baer, M., Dirks, K. T., and Nickerson, J. A. (2013). Microfoundations of strategic problem formulation. Strategic Manage. J. 34, 197–214. doi: 10.1002/smj.2004

Baker, W. E., and Sinkula, J. M. (1999). The synergistic effect of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 27, 411. doi: 10.1177/0092070399274002

Battisti, M., Beynon, M., Pickernell, D., and Deakins, D. (2019). Surviving or thriving: the role of learning for the resilient performance of small firms. J. Bus. Res. 100, 38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.006

Belrhiti, Z., Nebot Geralt, A., and Marchal, B. (2018). Complex leadership in healthcare: a scoping review. Int. J. Health Policy Manage. 7, 1073–1084. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.75

Bhaskara, G. I., and Filimonau, V. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational learning for disaster planning and management: a perspective of tourism businesses from a destination prone to consecutive disasters. J. Hosp. Tourism Manage. 46, 364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.011

Boin, A., Comfort, L. K., and Demchak, C. C. (2010). “The rise of resilience,” in Designing Resilience: Preparing for Extreme Events , editors L. K. Comfort, A. Boin, and C. C. Demchak (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press).

Boin, A., and Lodge, M. (2016). Designing Resilient Institutions for transboundary crisis management: a time for public administration. Public Adm. 94, 289–298. doi: 10.1111/padm.12264

Boin, A., and van Eeten, M. J. G. (2013). The resilient organization. Public Manage. Rev. 15, 429–445. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.769856

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Bragatto, P., Vairo, T., Milazzo, M. F., and Fabiano, B. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the safety management in Italian Seveso industries. J. Loss Prevent. Process Ind. 70, 104393. doi: 10.1016/j.jlp.2021.104393

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Britt, T. W., Shen, W., Sinclair, R. R., Grossman, M. R., and Klieger, D. M. (2016). How Much do we really know about employee resilience? Ind. Organ. Psychol. 9, 378–404. doi: 10.1017/iop.2015.107

Chand, A. M., and Loosemore, M. (2016). Hospital learning from extreme weather events: using causal loop diagrams. Build. Res. Inform. 44, 875–888. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2016.1097805

Chen, K. D., Li, Y. H., and Linderman, K. (2021). Supply network resilience learning: an exploratory data analytics study. Decision Sci. 20, 1–20. doi: 10.1111/deci.12513

Chen, R., Xie, Y., and Liu, Y. (2021). Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring organizational resilience: a multiple case study. Sustainability 13, 2517. doi: 10.3390/su13052517

Chiva, R., Ghauri, P., and Alegre, J. (2014). Organizational learning, innovation and internationalization: a complex system model. Br. J. Manage. 25, 687–705. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12026

Christianson, M. K., Farkas, M. T., Sutcliffe, K. M., and Weick, K. E. (2009). Learning through rare events: significant interruptions at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum. Organization Sci. 20, 846–860. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0389

Cook, S. D. N., and Yanow, D. (1993). Culture and organizational learning. J. Manage. Inquiry 2, 373–390. doi: 10.1177/105649269324010

Cooper, H. M. (1988). Organizing knowledge syntheses: a taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge Soc. 1, 104. doi: 10.1007/BF03177550

Crick, R., and Bentley, J. (2020). Becoming a resilient organisation: integrating people and practice in infrastructure services. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 13, 423–440. doi: 10.1080/19397038.2020.1750738

Crossan, M. M., and Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: a systematic review of the literature. J. Manage. Stud. 47, 1154–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., and White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution. Acad. Manage. Rev. 24, 522–537. doi: 10.2307/259140

Dohaney, J., de Roiste, M., Salmon, R. A., and Sutherland, K. (2020). Benefits, barriers, and incentives for improved resilience to disruption in university teaching. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 50, 9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101691

Donahue, A., and Tuohy, R. (2006). Lessons we don't learn: a study of the lessons of disasters, why we repeat them, and how we can learn them. Homeland Security Affairs 2, 4. Available online at: https://www.hsaj.org/articles/167 (accessed December 10, 2021).

Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 13, 215–246. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

Duchek, S., Raetze, S., and Scheuch, I. (2020). The role of diversity in organizational resilience: a theoretical framework. Bus. Res. 13, 387–423. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0084-8

Dutra, L. X. C., Bustamante, R. H., Sporne, I., van Putten, I., Dichmont, C. M., Ligtermoet, E., et al. (2015). Organizational drivers that strengthen adaptive capacity in the coastal zone of Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 109, 64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.02.008

Ekstedt, M., and Odegard, S. (2015). Exploring gaps in cancer care using a systems safety perspective. Cogn. Technol. Work 17, 5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10111-014-0311-1

Elliott, D., and Macpherson, A. (2010). Policy and practice: recursive learning from crisis. Group Org. Manage. 35, 572–605. doi: 10.1177/1059601110383406

Ellis, S., and Shpielberg, N. (2003). Organizational learning mechanisms and managers' perceived uncertainty. Hum. Relat. 56, 1233–1254. doi: 10.1177/00187267035610004

Fannoun, S., and Kerins, J. (2019). Towards organisational learning enhancement: assessing software engineering practice. Learn. Org. 26, 44–59. doi: 10.1108/TLO-09-2018-0149

Fasey, K. J., Sarkar, M., Wagstaff, C. R. D., and Johnston, J. (2021). Defining and characterizing organizational resilience in elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 52, 12. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101834

Fiol, M., and O'Connor, E. (2017). Unlearning established organizational routines – Part I. Learn. Org. 24, 13–29. doi: 10.1108/TLO-09-2016-0056

Folke, C., Carpenter, S., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Elmqvist, T., Gunderson, L., et al. (2004). Regime shifts, resilience, and biodiversity in ecosystem management. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 557–581. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.021103.105711

Friday, D., Savage, D. A., Melnyk, S. A., Harrison, N., Ryan, S., and Wechtler, H. (2021). A collaborative approach to maintaining optimal inventory and mitigating stockout risks during a pandemic: capabilities for enabling health-care supply chain resilience. J. Hum. Logistics Supply Chain Manage. 11, 24. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-07-2020-0061

Fridell, M., Edwin, S., von Schreeb, J., and Saulnier, D. D. (2020). Health system resilience: what are we talking about? A scoping review mapping characteristics and keywords. Int. J. Health Policy Manage. 9, 6–16. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.71

Garvin, D. A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 71, 78–91.

Garvin, D. A., Edmondson, A. C., and Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning organization? Harvard Bus. Rev. 86, 109–116, 134. Available online at: https://hbr.org/2008/03/is-yours-a-learning-organization (accessed December 5, 2021).

Gherardi, S. (2008). “Situated knowledge and situated action: What do practice-based studies promise?,” in The SAGE Handbook of New Approaches in Management and Organization , editors D. Barry and H. Hansen (Los Angeles, CA: Sage), 516–525.

Gherardi, S., and Nicolini, D. (2002). Learning in a constellation of interconnected practices: canon or dissonance? J. Manage. Stud. 39, 419–436. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.t01-1-00298

Gherardi, S., Nicolini, D., and Odella, F. (1998). Toward a social understanding of how people learn in organizations:the notion of situated curriculum. Manage. Learn. 29, 273–297. doi: 10.1177/1350507698293002

Gilson, L., Ellokor, S., Lehmann, U., and Brady, L. (2020). Organizational change and everyday health system resilience: lessons from Cape Town, South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 266, 10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113407

Giustiniano, L., Clegg, S. R., Cunha, M. P., and Rego, A. (2018). Elgar Introduction to Theories of Organizational Resilience . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.4337/9781786437044

Gressgard, L. J., and Hansen, K. (2015). Knowledge exchange and learning from failures in distributed environments: the role of contractor relationship management and work characteristics. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 133, 167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2014.09.010

Grisold, T., Klammer, A., and Kragulj, F. (2020). Two forms of organizational unlearning: insights from engaged scholarship research with change consultants. Manage. Learn. 51, 598–619. doi: 10.1177/1350507620916042

Habiyaremye, A. (2021). Co-operative learning and resilience to COVID-19 in a small-sized South African enterprise. Sustainability 13, 17. doi: 10.3390/su13041976

Hardy, T. L. (2014). “Resilience: a holistic safety approach,” in 2014 60th Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (New York).

Hecht, A. A., Biehl, E., Barnett, D. J., and Neff, R. A. (2019). Urban food supply chain resilience for crises threatening food security: a qualitative study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 119, 211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.001

Hegde, S., Hettinger, A. Z., Fairbanks, R. J., Wreathall, J., Krevat, S. A., and Bisantz, A. M. (2020a). Knowledge elicitation to understand resilience: a method and findings from a health care case study. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 14, 75–95. doi: 10.1177/1555343419877719

Hegde, S., Hettinger, A. Z., Fairbanks, R. J., Wreathall, J., Krevat, S. A., Jackson, C. D., et al. (2020b). Qualitative findings from a pilot stage implementation of a novel organizational learning tool toward operationalizing the Safety-II paradigm in health care. Appl. Ergon. 82, 8. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102913

Herbane, B. (2019). Rethinking organizational resilience and strategic renewal in SMEs. Entrepreneurship Regional Dev. 31, 476–495. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2018.1541594

Hermelin, J., Bengtsson, K., Woltjer, R., Trnka, J., Thorstensson, M., Pettersson, J., et al. (2020). Operationalising resilience for disaster medicine practitioners: capability development through training, simulation and reflection. Cogn. Technol. Work 22, 667–683. doi: 10.1007/s10111-019-00587-y

Hernes, T., and Irgens, E. J. (2013). Keeping things mindfully on track: organizational learning under continuity. Manage. Learn. 44, 253–266. doi: 10.1177/1350507612445258

Hillmann, J., Duchek, S., Meyr, J., and Guenther, E. (2018). Educating future managers for developing resilient organizations: the role of scenario planning. J. Manage. Educ. 42, 461–495. doi: 10.1177/1052562918766350

Hillmann, J., and Guenther, E. (2021). Organizational resilience: a valuable construct for management research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 23, 7–44. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12239

Hollnagel, E. (2011). “Prologue: the scope of resilience engineering,” in Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook , editors E. Hollnagel, J. Pariès, D. Woods, and J. Wreathall (England: Surrey: Taylor & Francis Group), 30–41.

Huber, G. P. (1991). Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures. Org. Sci. 2, 88–115. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2.1.88

Johannesen, D. T. S., Lindoe, P. H., and Wiig, S. (2020). Certification as support for resilience? Behind the curtains of a certification body: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20, 14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05608-5

Johnsen, S. O., and Habrekke, S. (2009). Can Organisational Learning Improve Safety and Resilience During Changes? Boca Raton: Crc Press-Taylor & Francis Group.

Johnsen, S. O., and Stene, T. (2014). Improving Human Resilience in Space and Distributed Environments by CRIOP. Boca Raton: CRC, FL Press/Taylor & Francis Group.

Jones, O., and Macpherson, A. (2006). Inter-organizational learning and strategic renewal in SMEs: extending the 4I framework. Long Range Plann. 39, 155–175. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2005.02.012

Kayes, D. C. (2015). Organizational Resilience: How Learning Sustains Organizations in Crisis, Disaster, and Breakdown . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Khan, S. J., Deere, D., Leusch, F. D. L., Humpage, A., Jenkins, M., Cunliffe, D., et al. (2017). Lessons and guidance for the management of safe drinking water during extreme weather events. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 3, 262–277. doi: 10.1039/C6EW00165C

Khan, T. Z. A., Farooq, W., and Rasheed, H. (2019). Organizational resilience: a dynamic capability of complex systems. J. Manage. Res. 6, 1–26. doi: 10.29145//JMR/61/0601001

Klockner, K., and Meredith, P. (2020). Measuring resilience potentials: a pilot program using the resilience assessment grid. Safety 6, 17. doi: 10.3390/safety6040051

Kugley, S., Wade, A., Thomas, J., Mahood, Q., Jørgensen, A.-M. K., Hammerstrøm, K., et al. (2017). Searching for studies: a guide to information retrieval for Campbell systematic reviews. Campbell Syst. Rev. 13, 1–73. doi: 10.4073/cmg.2016.1

CrossRef Full Text

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lavie, D., Stettner, U., and Tushman, M. L. (2010). Exploration and exploitation within and across organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 4, 109–155. doi: 10.5465/19416521003691287

Lawrence, T. B., Mauws, M. K., Dyck, B., and Kleysen, R. F. (2005). The politics of organizational learning: integrating power into the 4I framework. Acad. Manage. Rev. 30, 180–191. doi: 10.5465/amr.2005.15281451

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., and Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resource Manage. Rev. 21, 243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001

Levinthal, D. A., and March, J. G. (1993). The myopia of learning. Strategic Manage. J. 14, 95–112. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250141009