- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Cybersecurity

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, review of prior work, hypotheses development, research method and analysis of findings, interpretation and discussion, conclusions, acknowledgements, appendix 1: profile of participant organizations and corresponding attacks characteristics, appendix 2: sample interview questions (phase 1), appendix 3: impact assessment exercise exemplar, appendix 4: sample interview questions (phase 2), appendix 5: criteria used to assess the security posture of organizations, appendix 6: security posture exemplars, appendix 7: profile of organizations.

- < Previous

An empirical study of ransomware attacks on organizations: an assessment of severity and salient factors affecting vulnerability

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lena Yuryna Connolly, David S Wall, Michael Lang, Bruce Oddson, An empirical study of ransomware attacks on organizations: an assessment of severity and salient factors affecting vulnerability, Journal of Cybersecurity , Volume 6, Issue 1, 2020, tyaa023, https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyaa023

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This study looks at the experiences of organizations that have fallen victim to ransomware attacks. Using quantitative and qualitative data of 55 ransomware cases drawn from 50 organizations in the UK and North America, we assessed the severity of the crypto-ransomware attacks experienced and looked at various factors to test if they had an influence on the degree of severity. An organization’s size was found to have no effect on the degree of severity of the attack, but the sector was found to be relevant, with private sector organizations feeling the pain much more severely than those in the public sector. Moreover, an organization’s security posture influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack. We did not find that the attack target (i.e. human or machine) or the crypto-ransomware propagation class had any significant bearing on the severity of the outcome, but attacks that were purposefully directed at specific victims wreaked more damage than opportunistic ones.

In recent years, Europol’s annual Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment report has consistently identified ransomware as a top priority; their latest bulletin states that ‘ransomware remains one of the, if not the, most dominant threats, especially for public and private organisations within as well as outside Europe’ [ 1 ]. Furthermore, as starkly evidenced by an international survey of 5000 IT managers, the incidence of ransomware attacks is growing exponentially [ 2 ]. Similar trends have been observed by government and law enforcement bodies [ 3 , 4 ]. Ransomware attacks can potentially generate substantial financial rewards for offenders, but the ransom – which in most cases is not paid – is just a fraction of the overall cost of the attack in terms of reputational damage and loss of business [ 3 , 5 ].

Since ransomware first arrived on the scene in a major way about the year 2013, the volume of academic literature produced on this topic has mushroomed. Important advances such as sophisticated detection methods and innovative intrusion prevention systems have been put forward. Organizations are advised to implement effective security education, introduce policies and technical controls, install antivirus software, promote strong e-mail hygiene, upgrade old systems, execute regular patching, apply the ‘least privileges’ approach, segregate the network perimeter and implement effective backup practices [ 6 , 7 ]. Although the aforementioned types of work are of tremendous importance to a preventative strategy, they are not by themselves sufficient. This is because most of the research on ransomware to date has focused primarily on its technical aspects, with comparatively little attention being given to understanding the socio-technical side of the attack or the characteristics of organizations [ 8 ]. So, while there is a strong emphasis on developing ransomware countermeasures, there is a lack of studies that examine the real experiences of organizations that have actually fallen victim to ransomware attacks.

It may be tempting to assume certain things about what makes an organization more or less vulnerable to an attack, but we should not be so presumptuous. Although research on cybercrime victimization has significantly expanded over the past two decades, the majority of studies focus on individual-level offences such as online bullying, harassment and stalking. Holt and Bossler [ 9 ] make the point that for some types of cybercrime, such as malware and ransomware, our understanding of what causes individuals and organizations to fall victim is not well developed. Our work addresses this limitation by focusing on ransomware crime and collecting data from the actual victims of ransomware.

Generally, the risk of cybercrime victimization has been addressed by studying characteristics of the offender [ 10 ], the victim [ 11 ] and the crime itself [ 12 ]. Our article focuses on the latter two and is motivated by several calls in the literature to better understand typical victims of ransomware attacks, with a view towards developing solutions that prevent or mitigate this sinister problem [ 9 , 13 , 14 ].

To date, only a small number of studies have directly looked at the experiences of organizations that have fallen victim to ransomware. Of these few (see Table 1 ), the majority consider things at a rather cursory level. Our study, which is based on a substantial sample of 55 ransomware attacks and draws upon qualitative and quantitative data, helps to address this gap in the literature by presenting detailed findings on the antecedents and consequences of actual ransomware attacks within 50 organizations. Our objectives were to

Previous empirical studies of ransomware attacks on organizations

| Authors . | Country . | Method . | Sample . | Main findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi . [ ] | USA | Quantitative analysis of secondary data | 13 reported attacks on police departments from 2013 to 2016 | Online lifestyle and cybersecurity stance contribute to ransomware victimization |

| Zhao . [ ] | USA | Mixed methods case study: questionnaire and interviews | Medical students and surgeons in a hospital that experienced a SamSam ransomware attack (29 survey respondents; 8 interviewees) | Students who are ‘digital natives’ were seriously stressed by lack of access to electronic resources and were not well adapted to adjust to paper-based workflows |

| Zhang-Kennedy . [ ] | USA | Mixed methods case study: questionnaire and interviews | Staff and students in a large university that experienced a ransomware attack at a critical time (150 survey respondents; 30 interviewees) | It took several days to recover basic services and the after-effects on user productivity were felt for a considerable time afterward. Substantial data loss and emotional effects on staff. |

| Hull . [ ] | UK | Mixed methods: questionnaire and interviews | 46 questionnaire respondents and 8 interviews (university staff, students and SMEs) | Universities are more likely to be attacked than SMEs; ransomware victims only had basic defences in place |

| Shinde . [ ] | The Netherlands | Mixed methods: questionnaire and interviews | Snowball sample of 23 individuals and 2 semi-structured interviews | Most ransomware attacks use an untargeted ‘shotgun’ approach; security awareness among victims was low |

| Ioanid . [ ] | Romania | Questionnaire | Survey of 123 SMEs | Organization size and turnover is positively correlated with number of attacks; manager education is key prevention factor |

| Byrne and Thorpe [ ] | Ireland | Brief interviews | Three organizations that had suffered attacks | E-mail filtering software had been removed because of the overhead it was placing on IT departments; in the wake of attacks, security training and awareness programmes were ramped up. |

| Riglietti [ ] | Not stated | Content analysis of discussions | 301 posts extracted from four online security blogs | Content analysis technique can increase our understanding of security challenges within organizations |

| Authors . | Country . | Method . | Sample . | Main findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi . [ ] | USA | Quantitative analysis of secondary data | 13 reported attacks on police departments from 2013 to 2016 | Online lifestyle and cybersecurity stance contribute to ransomware victimization |

| Zhao . [ ] | USA | Mixed methods case study: questionnaire and interviews | Medical students and surgeons in a hospital that experienced a SamSam ransomware attack (29 survey respondents; 8 interviewees) | Students who are ‘digital natives’ were seriously stressed by lack of access to electronic resources and were not well adapted to adjust to paper-based workflows |

| Zhang-Kennedy . [ ] | USA | Mixed methods case study: questionnaire and interviews | Staff and students in a large university that experienced a ransomware attack at a critical time (150 survey respondents; 30 interviewees) | It took several days to recover basic services and the after-effects on user productivity were felt for a considerable time afterward. Substantial data loss and emotional effects on staff. |

| Hull . [ ] | UK | Mixed methods: questionnaire and interviews | 46 questionnaire respondents and 8 interviews (university staff, students and SMEs) | Universities are more likely to be attacked than SMEs; ransomware victims only had basic defences in place |

| Shinde . [ ] | The Netherlands | Mixed methods: questionnaire and interviews | Snowball sample of 23 individuals and 2 semi-structured interviews | Most ransomware attacks use an untargeted ‘shotgun’ approach; security awareness among victims was low |

| Ioanid . [ ] | Romania | Questionnaire | Survey of 123 SMEs | Organization size and turnover is positively correlated with number of attacks; manager education is key prevention factor |

| Byrne and Thorpe [ ] | Ireland | Brief interviews | Three organizations that had suffered attacks | E-mail filtering software had been removed because of the overhead it was placing on IT departments; in the wake of attacks, security training and awareness programmes were ramped up. |

| Riglietti [ ] | Not stated | Content analysis of discussions | 301 posts extracted from four online security blogs | Content analysis technique can increase our understanding of security challenges within organizations |

Assess the degree of severity of ransomware attacks within organizations;

Explore how characteristics of the organization and characteristics of the attack affect the severity of the outcome.

Within the literature on cybercrime in general, there have been various efforts to understand the factors that make individuals more prone to becoming victims. Drawing upon Lifestyle Theory and Routine Activity Theory, Agustina [ 23 ] proposes several behavioural and environmental factors that should, in theory at least, elevate the risk of being victimized. In practice, however, as found by Ngo and Paternoster [ 24 ], these theories do not hold up to empirical scrutiny. Our work differs from these previous studies in two ways: first, we are looking not at cybercrime in general, but specifically at ransomware attacks; secondly, our focus is not on individual victims, but rather on organizations.

Although several reports [ 1–4 ] suggest that the number of ransomware attacks against businesses continues to rise steadily, it is hard to form any clear sense of the true extent of ransomware attacks. The difficulty of accurately measuring and comparing cybercrime rates has been remarked upon by Furnell et al . [ 25 ]. Statistics about the incidence of ransomware attacks vary wildly. In an international study based on 574 participants across 77 countries, BCI [ 26 ] reported that 31% of respondents had been afflicted by ransomware. In contrast, a large-scale survey of Internet users in Germany revealed that only 3.6% of individuals had suffered a ransomware attack [ 27 ]. Simoiu et al . [ 5 ] estimated that about 2–3% of their sample of 1180 American adults were hit by ransomware between 2016 and 2017. Similarly, Ioanid et al . [ 20 ] reported that 2% of their sample of 103 Romanian small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) were affected by the WannaCry attack that year. Against those low incidence rates, Hull et al . [ 18 ] found that as many as 61% of UK respondents had experienced at least one attack, and Shinde et al . [ 19 ] reported that 20% of respondents to their survey in the Netherlands were victims of ransomware, although it must be acknowledged that both those studies were based on quite small samples. All of these conflicting survey findings create a rather muddled picture. This, of course, can be put down to differences in sampling methods, response rates, temporal factors and units of analysis, but our essential point is this: it is generally agreed that ransomware presents a grave threat and has adversely affected many organizations, yet we know very little about the experiences of organizations that were attacked or the root causes that left them open to a successful violation.

There are very few empirical studies of the impact of ransomware within organizations or the factors that make organizations vulnerable. Al-Rimy et al . [ 28 ] present a literature survey of ransomware threat success factors, but the scope of their work extends only to infection vectors and enabling technologies (i.e. cryptography techniques, payment methods, ransomware development kits). They do not consider any organizational or socio-technical factors.

Our extensive search of the literature revealed just a handful of studies that looked directly at the experiences of organizations that were victims of ransomware (see Table 1 ). To summarize the key findings of these studies: ransomware attacks had major financial and emotional impact on victims, and the common factors that led to the attacks seemed to be a lack of security education or diligence, with organization type and size also emerging as possible factors impacting the likelihood of an attack.

Byrne and Thorpe [ 21 ] observe that ‘there is a gap in the literature with regards to examining the issue [of ransomware] from a company's perspective and that of its user base.’ Our study aims to make a contribution towards addressing this gap. In the next sections, we present a number of factors that we believe might affect the vulnerability of an organization to a ransomware attack, as well as characteristics of the attack weapon and method that could affect the severity of impact.

Organization characteristics: size and sector

As with so much of the reported facts and figures pertaining to ransomware, there is disagreement as to whether an organization’s size makes it more or less susceptible to attack. An international survey conducted by BCI [ 26 ] found that ransomware attacks are a substantially more common problem for large enterprises than they are for SMEs. However, contradictory findings are reported by Beazley [ 27 ] who state that SMEs were disproportionately hit by ransomware attacks in 2018, with 71% of all infections occurring within such organizations.

Many SMEs based in the UK believe that they are not likely to be targeted by ransomware attacks; while they place high value on the importance of IT to their business, they are generally not worried about the threat of data loss [ 29 , 30 ]. SMEs, by their entrepreneurial nature, are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviour [ 31 ]. However, SMEs may underestimate the value to hackers of their information systems and may not realize that they could be targeted as a hop to gain entry into their partners’ networks. As Smith [ 32 ] puts it, ‘even if you think your company has nothing worth stealing, losing access to all your data is no longer an unlikely event.’ Kurpjuhn [ 33 ] makes the point that SMEs must accept that they are exposed to similar levels of risk as large enterprises but have lower budgets and lesser resources to address those risks.

An argument could be made that larger organizations, simply because they employ more people, are at greater risk of infection due to human error; it only takes one reckless act by a single individual to compromise an entire network. Although not quite the same thing, Bergmann et al . [ 34 ] found no correlation between the size of a household and the rate of cybercrime victimization experienced by members of that household. How that finding would scale up to larger units in a non-domestic setting is a matter of conjecture, but it seems reasonable to assume that the potential for human error increases relative to the size of the unit.

Hypothesis 1a: An organization’s size influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack.

Hypothesis 1b : An organization’s sector influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack.

Security posture

Because ransomware combines technical and social characteristics to create its impact, we explore the organizational victim responses to attacks through the lens of ‘security posture’. Security posture is defined as ‘the security status of an enterprise’s networks, information, and systems based on information assurance resources (e.g., people, hardware, software, policies) and capabilities in place to manage the defense of the enterprise and to react as the situation changes’ [ 36 ]. Prior research into ransomware attacks on organizations shows that a lack of basic security practices, or failure to comply with them, was a common failing [ 15 , 18 ]. Organizations that do not have adequate and effective backup strategies are much more likely to end up having to pay the ransom to retrieve their data [ 15 , 28 ]. Connolly and Wall [ 8 ] developed a taxonomy of ransomware countermeasures, emphasizing a multi-layered approach in protecting organizations against ransomware.

While technical defence mechanisms are very important, so too is individual behaviour and good ‘online lifestyle’. Inadequate care by employees when choosing to open e-mail attachments or hyperlinks, downloading ‘free’ versions of software or cracked games, browsing adult content or illegal sports live streams, and installing apps from untrusted sources are all examples of poor online hygiene that can increase the risk of a ransomware infection. Riglietti [ 28 ] observed that ‘looking at what users say, avoiding infection appears to be a matter of spreading the right security culture within an organisation rather than a technical issue.’ A key part of this is education and awareness [ 37 , 38 ]. In their studies of ransomware victims, Shinde et al . [ 19 ] and Zhang-Kennedy et al . [ 27 ] both observed a tendency by employees to assume that cybersecurity was essentially the responsibility of the IT Department. While it is to be expected that the IT Department should take the lead on security and actively promote a strong posture, there is an onus on individuals to utilize good personal security practices and not engage in irresponsible behaviour.

Hypothesis 1c: An organization’s security posture influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack.

Crypto-ransomware propagation class

Since crypto-ransomware was incapable of propagating on networks prior to 2013, we decided to create a simple taxonomy according to the degree of infectiousness (see Table 2 ). Different propagation classes of crypto-ransomware may have a lesser or greater effect on the outcome of a crypto-ransomware attack as a result of the volume of infection spread.

Classification by crypto-ransomware propagation

| Crypto-ransomware propagation class . | Description . | Examples . |

|---|---|---|

| Generation I | Early variants of crypto-ransomware were not able to spread on networks and had limited propagation capabilities even within an infected machine (prior 2013). | AIDS Information GPCoder |

| Generation II | First emerged in 2013, this type can propagate by taking advantage of network paths. Generation II crypto-ransomware can encrypt devices that are physically and logically (e.g. ‘write’ access to server shares) connected to the infected machine. A common attack vector of Generation II crypto-ransomware is a malicious e-mail. | CryptoLocker CryptoWall CryptoDefence |

| Generation III.a (Trojans) | First emerged in 2016, this type uses various tools (e.g. password-stealer Mimikatz) and takes advantage of network weaknesses to propagate on infected networks. These variants can infect entire networks, completely crippling an organization’s ability to function. Generation III.a crypto-ransomware normally penetrates network via vulnerable servers. | Samas BitPaymer |

| Generation III.b (Worms) | First emerged in 2017, Generation III.b crypto-ransomware, also commonly referred as ‘crypto-worms’, takes advantage of software vulnerabilities. Similar to variants like Samas and BitPaymer, crypto-worms can infect entire networks. | WannaCry NotPetya |

| Crypto-ransomware propagation class . | Description . | Examples . |

|---|---|---|

| Generation I | Early variants of crypto-ransomware were not able to spread on networks and had limited propagation capabilities even within an infected machine (prior 2013). | AIDS Information GPCoder |

| Generation II | First emerged in 2013, this type can propagate by taking advantage of network paths. Generation II crypto-ransomware can encrypt devices that are physically and logically (e.g. ‘write’ access to server shares) connected to the infected machine. A common attack vector of Generation II crypto-ransomware is a malicious e-mail. | CryptoLocker CryptoWall CryptoDefence |

| Generation III.a (Trojans) | First emerged in 2016, this type uses various tools (e.g. password-stealer Mimikatz) and takes advantage of network weaknesses to propagate on infected networks. These variants can infect entire networks, completely crippling an organization’s ability to function. Generation III.a crypto-ransomware normally penetrates network via vulnerable servers. | Samas BitPaymer |

| Generation III.b (Worms) | First emerged in 2017, Generation III.b crypto-ransomware, also commonly referred as ‘crypto-worms’, takes advantage of software vulnerabilities. Similar to variants like Samas and BitPaymer, crypto-worms can infect entire networks. | WannaCry NotPetya |

What we term ‘Generation I’ crypto-ransomware was not particularly effective in extorting money due to several technological shortcomings, such as the use of easy-to-break encryption, inefficient management of decryption keys and limited propagation capabilities. It is highly likely that Generation I variants are obsolete.

We refer to variants such as CryptoWall, CryptoLocker and CryptoDefence as ‘Generation II’. These forms of ransomware initially penetrate networks via desktops or laptops and subsequently take advantage of the local user security context to spread via network paths, encrypting network shares that the user has ‘write’ access to. They can also encrypt devices physically connected to the infected machine.

What we refer to as ‘Generation III.a’ malware are those such as Samas and BitPaymer that tend to breach networks via vulnerabilities found in servers [e.g. a weak password in Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP)]. Once inside the server, attackers manually and/or automatically search for various weaknesses within the network (e.g. poor authentication controls, a flat network structure, the lack of network visibility and detection mechanisms). Such vulnerabilities permit attackers to stay undetected and hijack multiple devices and the entire network in some cases. Crypto-worms like WannaCry (‘Generation III.b’ in our classification) have a similar devastating effect, the chief difference being that they take advantage exclusively of software vulnerabilities in order to propagate.

Hypothesis 2a: The crypto-ransomware propagation class influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack.

Attack type and target

Hypothesis 2b : The attack type, i.e. opportunistic or targeted, influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack.

Hypothesis 2c : The attack target, i.e. human or machine, influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack

This study used a mixed methods approach following an exploratory sequential design [ 43 ]. Phase 1 was qualitative. In order to assess the degree of severity of ransomware attacks (our first objective), we required a measurement instrument. A literature search revealed that there are no readily available tools for this particular purpose. Since crypto-ransomware incidents entail some unique consequences (e.g. encrypted data, disabled systems), we could not use substitutes from other cybercrime studies; the assessment instrument had to be specific to crypto-ransomware attacks. Hence, the aim of Phase 1 was to inductively develop an Impact Assessment Instrument (grounded in empirical data) that can be used to effectively evaluate the severity of crypto-ransomware attacks on organizations in our sample. In Phase 2, we gathered additional quantitative data so as to be able to statistically test our hypotheses.

The Ethics Committee at the University of Leeds approved this research. Consent forms were signed by all study participants. All necessary precautions were followed to ensure the anonymity of study participants and the confidentiality of collected data. The majority of participants were from the UK but there were also a few from North America. Where the names of organizations are subsequently referred to in this article, aliases are used to protect the anonymity of respondents (see Appendix 1 ). Additionally, interviewees from UK Police Cybercrime Units are given the aliases of CyberRM, CyberLM, CyberTL, CyberBR, CyberBL, CyberTR and CyberCU. Incidents took place between 2014 and 2018.

Sampling strategy and data collection

A purposeful sampling approach was employed to collect data in Phase 1. We conducted 10 semi-structured interviews with professionals from organizations that became victims of ransomware attacks. Interviewees were IT/Security Managers and Executive Managers with an average of 17 years of professional experience. There was one respondent per organization. Since some organizations were attacked more than once, accounts of 15 ransomware incidents were elicited from 10 organizations. Appendix 1 (please refer to first 15 incidents) contains information about the characteristics of attacks and organizations that were interviewed in Phase 1.

In order to enhance the reliability and richness of data, we sought access to individuals who had direct experience of responding to crypto-ransomware incidents. As for crypto-ransomware attacks, the key selection criteria was to include a range of consequences for the victims, varying from low severity (e.g. minimum disruption to business, minimum loss of information, swift recovery) to high impact (e.g. business disruption that lasted for several months, significant loss of critical information, slow recovery).

An interview guide was designed with the aim to learn about participants’ perceptions of the attacks’ impact and the factors that aggravated or moderated the consequences of these incidents. This exercise guided the development of the Impact Assessment Instrument. Since we planned to use these initial 15 cases in Phase 2 of data analyses, we also ensured to collect profile information about organizations (e.g. size, sector and industry), causes of crypto-ransomware attacks, information about security postures and characteristics of attacks (e.g. attack type, crypto-ransomware propagation class and attack vector). Sample interview questions are provided in Appendix 2 . Six interviews were conducted face-to-face, three via Skype with overseas respondents and one via e-mail correspondence.

The decision to stop data collection in qualitative research is made when additional insights are not emerging with new observations. This point is typically achieved after a dozen or so observations [ 44 ]. We felt that after examining about 10 ransomware incidents, the incremental learning stopped. But to ensure that the point of ‘theoretical saturation’ is sufficiently reached, we collected data on 15 cases in total.

Impact Assessment Instrument development (qualitative data analysis)

An inductive content analysis method was used to analyse data and develop the Impact Assessment Instrument. Within the interview transcripts, the impact of crypto-ransomware incidents emerged as a major topic. Interviewees eagerly described their experiences of being attacked, particularly focusing on the consequences of crypto-ransomware attacks. For example, respondents from GovSecJN, EducInstFB, LawEnfM, GovSecA and HealthSerJU spoke in great detail about the despair and distress they experienced. An IT/Security Manager from GovSecJN, a large public sector organization, explained how business continuity disruption affected them:

There was an impact on service delivery – we could not do what we were supposed to do. It was significant for us. Besides, all our resources were directed towards the incident instead of doing our job.

An IT/Security Manager from LawEnfJU reported a similar experience:

Ransomware encrypted all of our data files, which, in effect, took the agency offline for about 10 days. This was extremely critical as we could not do our job. We had the server up-and-running in 10 days and then it took another 10 days to manually re-enter all data. So, the attack critically affected the operations of the department for about 20 days … . The overall impact of this attack was severe, definitely.

An Executive Manager from EducInstFB, a large public organization, shared with us that a Generation III.a crypto-ransomware encrypted hundreds of machines (desktops, laptops and servers). As a result, several critical business functions were disabled and important data were inaccessible. The victim disclosed that various security holes – including ineffective backups, poor patching regimes, the lack of network visibility and feeble access control management practices – led to infection and subsequent dramatic consequences.

GovSecA, a large public organization, suffered an unprecedented attack by Generation III.a crypto-ransomware, where close on 100 servers got encrypted, affecting the operations of the organization for months. Most importantly, the victim lost a lot of critical data because they only had partial backups. At the time of the interview, GovSecA was already in post-attack recovery for 8 months. The interviewee shared that the recovery was still not completed at this point. An IT/Security Manager from GovSecA described their experience as follows:

We all came back to work on Tuesday morning after a bank holiday weekend and the sun was streaming in through the windows. The cleaners have been in, the office looked great. Everyone felt refreshed after the long weekend. And it took a while for us to realise what happened; that all computing had been turned to stone [encrypted]. Virtually nothing was left untouched. If half of the building had fallen off, you would understand that something has happened. But everything looked great. But it was not – the organisation could not operate.

An Executive Police Officer from LawEnfM, a public SME, described how the organization suffered two ransomware attacks within 2 weeks, affecting critical data:

We are a full-service law enforcement agency and we have a wide variety of data, some of which is very sensitive. For example, data relevant to criminal incidents like manslaughter cases, child pornography, child sex cases. Several months worth of this data was encrypted, which was pretty significant to us … . While we were recovering after the first attack, we were very unfortunate to get infected by ransomware again.

Comments such as in these few selected excerpts featured regularly in the interviews. We observed that when victims described the impact of ransomware attacks, they focused on factors such as business continuity disruption, recovery time, the number of devices affected, how critical encrypted information was to business and information loss.

On the contrary, interviewees from LawEnfJ and GovSecJ talked about factors that effectively saved the organization from far worse outcomes and emphasized that organizations must be prepared for these attacks or suffer severe consequences. For example, an IT/Security Manager from LawEnfJ, a public SME, shared the following:

We practice good basic security principles. We have backups in multiple locations … . It comes down to basics like staying up to date with industry. Just recently we went through this massive patching for Intel processors and other processes that could be leveraged into a whole host of attacks … . We were well-prepared for the attack … . We restored everything over a weekend. We were infected on Friday and back up-and-running on Monday.

Similarly, an IT/Security Manager from GovSecJ, a large public organization, explained how they were able to recover with little inconvenience:

An Incident Management Plan is crucial during cyber-attacks. Instead of running around with our hands up in the area, screaming for help, our response was logical and structured … . We lost some data due to incremental backups but nothing significant that would have stopped an organisation from functioning … . The infection took place at approximately 9 in the morning. By the end of the day, data was restored, and everything was back to normal.

As a result of our data analysis in Phase 1, five categories of negative outcomes emerged from the data, namely ‘business continuity disruption timeline’, ‘recovery time’, ‘affected devices’, ‘encrypted information critical to business’ and ‘information loss’. Under each of these categories, the data enabled us to build impact descriptors ranging across three degrees of severity (low, medium and high). In Table 3 , we present the severity descriptors for the five impact categories and corresponding attacks.

Impact Assessment Instrument and corresponding victims

| Impact item . | Degree of severity (3-point ordinal scale) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 = Low . | 2 = Medium . | 3 = High . | |

| Business continuity disruption timeframe | Up to 1 week | Up to 2 weeks | More than 2 weeks |

| Recovery time | Up to 1 week | Up to 1 month | Several months or more, if at all |

| Affected devices | One or more user devices, possibly including shares on one or more servers | Several devices and more than one server; or where a central server is encrypted affecting not just individual users but the functioning of a whole department | All or majority of devices, completely or almost completely crippling IT systems |

| Encrypted information critical to business | Some data compromised, but nothing critical | Data critical to some business functions of low to medium priority | Data critical to majority of business functions, or some high priority function(s) |

| Information loss | No loss, or some loss acceptable with incremental backups | Loss affecting some critical business functions | Loss affecting all or majority of critical business functions |

| Impact item . | Degree of severity (3-point ordinal scale) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 = Low . | 2 = Medium . | 3 = High . | |

| Business continuity disruption timeframe | Up to 1 week | Up to 2 weeks | More than 2 weeks |

| Recovery time | Up to 1 week | Up to 1 month | Several months or more, if at all |

| Affected devices | One or more user devices, possibly including shares on one or more servers | Several devices and more than one server; or where a central server is encrypted affecting not just individual users but the functioning of a whole department | All or majority of devices, completely or almost completely crippling IT systems |

| Encrypted information critical to business | Some data compromised, but nothing critical | Data critical to some business functions of low to medium priority | Data critical to majority of business functions, or some high priority function(s) |

| Information loss | No loss, or some loss acceptable with incremental backups | Loss affecting some critical business functions | Loss affecting all or majority of critical business functions |

Given the broad range of organization types and sectors in our sample, we anticipated that it would be difficult to arrive at a consensus on what constitutes ‘Low’, ‘Medium’ and ‘High’ levels of severity. For example, an outcome that might be regarded as being of ‘Low’ severity by one respondent could possibly be regarded as ‘High’ by another, depending on the nature of their business and level of dependency on critical IT systems. However, there was a remarkable degree of consistency among the respondents. There is a general acceptance that any ransomware attack, however minor, is likely to result in an interruption of at least a few days rather than hours. Thus, recovery times and business continuity disruption of a number of days (up to a week) were rated as being on the ‘Low’ end of the spectrum because, although any disruption is traumatic, in relative terms that is the least amount of time that is expected to be lost. As one interviewee put it,

Considering the impact and seriousness of the ransomware, it is going to sound strange, but I think that to only lose twelve hours worth of data is an acceptable outcome. If we had not backed up, we would have lost 47,000 files, clearly that would have been a far more significant issue. (IT/Security Manager, GovSecJN)

The Impact Assessment Instrument presented in Table 3 is derived from empirical data and reflects the actual consequences of crypto-ransomware attacks as described by the victims. All five of the items shown in the table are components of the overall severity of a ransomware attack. Because the five items are measured on a three-point ordinal scale, as opposed to a multiple-point continuous scale, we used the ordinal alpha coefficient [ 45 ] to test for internal reliability. The value for ordinal α = 0.96 which indicates a high degree of agreement between the five items.

To compute a composite score for overall severity, we considered using the average or median of the five items but decided to use the maximum. The logic behind this reasoning is that if any of the items is evaluated as ‘High’, it means that the attack represented a serious shock to the organization with major consequences. Therefore, a ‘High’ severity value for any single item trumps all the others, even if they all have lesser values. This also gets around the aforementioned problem whereby the assessment instrument might misevaluate a particular item as ‘Low’ when in fact, because of the organization’s circumstances, it should be ‘High’; in such cases, the likelihood is that at least one other item would have a ‘High’ rating and hence the overall severity would correctly be evaluated as ‘High’.

Next, using the Impact Assessment Instrument shown in Table 3 , we analysed all of the initial 15 cases (interview transcripts) to determine the extent of the attack impact. We assigned the degree of severity for all five categories for each impact item. An exemplar of this assessment exercise is provided in Appendix 3 .

We were conscious of the limitation that the initial version of the Impact Assessment Instrument was based on data collected from 10 public organizations, with no private businesses. To remedy this, as we collected data on a further 45 cases, including both public and private organizations, we asked interviewees to assess the severity of ransomware attacks using our scale (i.e. low, medium, high) and comment on the reasons for their answer. The purpose of this exercise was to validate our instrument and confirm that the categories that emerged initially were relevant across the whole sample. We also validated the instrument by consulting with experienced police officers. We found that the instrument gave a reliable measure of the severity of an incident as perceived by the victim.

In order to test our hypotheses, we required to collect more data on crypto-ransomware incidents. It has been widely acknowledged that collecting data on cyberattacks is extremely difficult. In Phase 1, it took us over 6 months to find organizations that were willing to share sensitive matters relevant to the attacks. Therefore, we made a decision to approach the data collection matter differently in Phase 2. Instead, we sought out police officers from UK Cybercrime Units who had extensive experience in dealing with crypto-ransomware attacks. Mainly, such experience included helping organizations to effectively respond to the attacks, understanding what caused them, providing emotional support to victims if necessary and offering post-attack advice. Our expectation was that each police officer would be able to provide relevant information on several ransomware incidents at the time, which would make the process of data collection more manageable.

We succeeded to connect with 10 police officers (four Detective Sergeants and six Detective Constables) and 1 Civilian Cybercrime Investigator, who provided information on 22 usable ransomware incidents via semi-structured interviews and one focus group. Two police officers were interviewed twice as they were able to add new information. The average professional experience of the study respondents was 19 years. We also managed to collect data on 22 more cases with a Detective Inspector, who, unfortunately, was not able to meet with us face-to-face but agreed to provide data via a structured questionnaire (sent over e-mail). Additionally, we interviewed an IT/Security Manager with over 20 years of professional experience, which added one final case to our database of ransomware incidents. Relevant information is available in Appendix 1 (Cases 16–60). Due to the aforementioned access constraints, a snowballing technique was used to collect data for Phase 2.

The questionnaire and second phase interview guide (see Appendix 4 ) were based on the Impact Assessment Instrument and hypotheses. We asked questions that would help us to assess the impact of an attack. We also collected profile information on organizations (e.g. size, sector and industry) and characteristics of attacks (e.g. attack type, crypto-ransomware propagation class and attack target). Additionally, we included questions that would help us classify the security posture of each organization. For this purpose, we used the taxonomy of crypto-ransomware countermeasures developed in our previous work [ 8 ]. The headings from this taxonomy served as a guide for questions. Therefore, in order to assess a security posture of organization victims, we asked interviewees about security education, policies and practices, technical measures and network security, the incident response strategy and the attitudes of management towards cybersecurity (see Appendix 5 ).

Overall, 45 additional cases of ransomware attacks were examined in Phase 2, bringing the total to 60 cases. For five of the 60 cases, there was insufficient data to be able to determine the overall impact severity, so those cases were discarded as being unusable, leaving us with 55 usable cases. Although a snowballing technique was used to collect data in Phase 2, our overall sample included organizations of different sizes and from different sectors. Attacks were recorded against both humans and machines by different crypto-ransomware propagation classes. Different levels of security posture were noted among participants, ranging from weak to strong. Finally, the sample contained opportunistic attacks as well as targeted ones.

For a few of the cases, we did not have values for all of the five items in the Impact Assessment; in those cases, we evaluated the overall impact based on the maximum of the items for which we had values, supported by an inspection of qualitative data from those cases. We found that this method of computing the composite score for overall severity gave the most accurate results, as validated using participants’ personal assessment of the attack impact and our own judgement based on what we gleaned from interviews. Results of the assessment exercise are available in Table 4 .

Impact Assessment Instrument and observed frequencies among respondents ( n = 55)

| Impact item . | Degree of severity (3-point ordinal scale) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 = Low . | 2 = Medium . | 3 = High . | |

| Business continuity disruption timeframe ( = 52) | Up to 1 week (65%) | Up to 2 weeks (14%) | More than 2 weeks (21%) |

| Recovery time ( = 51) | Up to 1 week (59%) | Up to 1 month (22%) | Several months or more, if at all (19%) |

| Affected devices ( = 53) | One or more user devices, possibly including shares on one or more servers (53%) | Several devices and more than one server; or where a central server is encrypted affecting not just individual users but the functioning of a whole department (19%) | All or majority of devices, completely or almost completely crippling IT systems (28%) |

| Encrypted information critical to business ( = 51) | Some data compromised, but nothing critical (29%) | Data critical to some business functions of low to medium priority (24%) | Data critical to majority of business functions, or some high priority function(s) (47%) |

| Information loss ( = 47) | No loss or some loss acceptable with incremental backups (57%) | Loss affecting some critical business functions (32%) | Loss affecting all or majority of critical business functions (11%) |

| Overall impact severity (composite score) ( = 55) | Low (27%) | Medium (20%) | High (53%) |

| Impact item . | Degree of severity (3-point ordinal scale) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 = Low . | 2 = Medium . | 3 = High . | |

| Business continuity disruption timeframe ( = 52) | Up to 1 week (65%) | Up to 2 weeks (14%) | More than 2 weeks (21%) |

| Recovery time ( = 51) | Up to 1 week (59%) | Up to 1 month (22%) | Several months or more, if at all (19%) |

| Affected devices ( = 53) | One or more user devices, possibly including shares on one or more servers (53%) | Several devices and more than one server; or where a central server is encrypted affecting not just individual users but the functioning of a whole department (19%) | All or majority of devices, completely or almost completely crippling IT systems (28%) |

| Encrypted information critical to business ( = 51) | Some data compromised, but nothing critical (29%) | Data critical to some business functions of low to medium priority (24%) | Data critical to majority of business functions, or some high priority function(s) (47%) |

| Information loss ( = 47) | No loss or some loss acceptable with incremental backups (57%) | Loss affecting some critical business functions (32%) | Loss affecting all or majority of critical business functions (11%) |

| Overall impact severity (composite score) ( = 55) | Low (27%) | Medium (20%) | High (53%) |

Note: Overall n = 55 but item response rates ranged from 85% (47) to 96% (53).

Quantitative data analysis

Overall, our sample included 50 organizations of different sizes, sectors (i.e. public or private) and industries (55 usable cases of crypto-ransomware attacks). Totally, 35 (70%) of the organizations were SMEs, while 15 (30%) were large organizations. We used the European Commission guidance to define the organization’s size [ 46 ]. The industries were broad and varied, including IT, government, law enforcement, education, healthcare, financial services, construction, retail, logistics, utility providers and several other categories. Of the 50 organizations, 19 (38%) were in the public sector and 31 (62%) were in the private sector. Five (10%) were located in the North America and 45 (90%) in the UK (see Appendix 7 ). Security postures were determined for 34 of the 50 organizations (see Table 5 ). Twenty organizations (59%) had a weak security posture, 13 (38%) had a medium-security posture and only one had a strong posture. We used the criteria outlined in Appendices 5 and 6 to assess the security postures of organizations.

Cross-tabulations for Hypotheses 1a, 1 b and 1c

| . | Attack severity, (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Medium . | High . | |

| H1a: Organization size ( = 50) | |||

| SME | 7 (20) | 8 (23) | 20 (57) |

| Large | 5 (33) | 2 (13) | 8 (53) |

| H1b: Sector ( = 50) | |||

| Public | 5 (26) | 7 (37) | 7 (37) |

| Private | 7 (23) | 3 (10) | 21 (68) |

| H1c: Security posture ( = 34) | |||

| Weak | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 16 (80) |

| Medium | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | 3 (23) |

| Strong | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| . | Attack severity, (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Medium . | High . | |

| H1a: Organization size ( = 50) | |||

| SME | 7 (20) | 8 (23) | 20 (57) |

| Large | 5 (33) | 2 (13) | 8 (53) |

| H1b: Sector ( = 50) | |||

| Public | 5 (26) | 7 (37) | 7 (37) |

| Private | 7 (23) | 3 (10) | 21 (68) |

| H1c: Security posture ( = 34) | |||

| Weak | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 16 (80) |

| Medium | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | 3 (23) |

| Strong | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001.

Except where otherwise stated, the hypotheses were assessed using two-sided Fisher’s Exact tests. The size of our sample provides acceptable power to detect moderate-to-large relationships between categorical variables using this technique. Where data was missing, cases were excluded; the number of relevant cases ( n ) is stated in the results of each test.

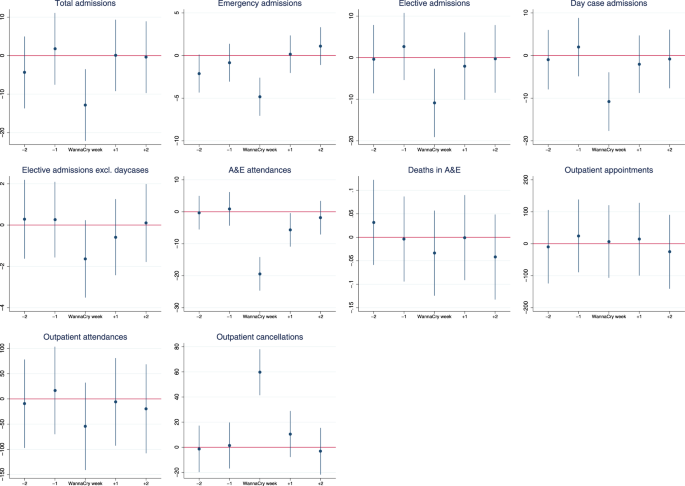

We found that the degree of severity of a ransomware attack did not vary by organizational size, P = 0.542. Indeed, the majority of attacks in both SMEs and large organizations were of high severity (57% and 53%, respectively).

The severity did, however, vary according to organizational sector. Private organizations were considerably more likely than public organizations to experience serious negative consequences as a result of ransomware attacks, P = 0.044. Of the private organizations, 68% were hit by attacks of the highest severity, whereas a much lower percentage (37%) of public organizations were as badly affected. This finding supports Hypothesis 1b.

Most tellingly, impacts also varied with organizational security posture, such that those organizations with weak security postures were far more likely to experience a severe impact than were those with medium or strong postures, n = 34, P < 0.001. Of the organizations that had a weak posture, 80% had been hit by ransomware attacks of high severity. Thus, Hypothesis 1c is also supported.

Post hoc, we found that security posture did not differ according to organization size, with the majority of organizations – 57% of SMEs and 64% of large organizations – having a weak security posture. However, when looking at the relationship between organization sector and security posture, a significant difference ( P = 0.035) was observed. Public organizations had considerably stronger security postures than those in the private sector. This may partly explain why the impact of attacks on public sector organizations was not as severe.

As can be seen in Appendix 1 , the 50 organizations spanned 23 different industries (i.e. financial services, healthcare, retail, etc.) so it was not meaningful to conduct correlation analysis on this variable as the numbers were spread too thin. However, one observation that stands out is that of the seven respondents from the IT industry, six of them (86%) experienced attacks of high severity. This is above average and somewhat surprising, although with such a small sub-sample it is not possible to draw reliable inferences.

Looking then at the crypto-ransomware propagation classes, 32 (58%) were of type Generation II, while 23 (42%) were of type Generation III (Generation III.a and Generation III.b classes were merged in data analysis due to similar propagation characteristics). Totally, 38 attacks (72%) were opportunistic and 15 (28%) were targeted. Twenty-five attacks (47%) were targeted at humans and 28 (53%) aimed at machines (see Table 6 ).

Cross-tabulations for Hypotheses 2a, 2 b and 2c

| . | Attack severity, (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Medium . | High . | |

| H2a: Crypto-ransomware type ( = 55) | |||

| Generation II | 10 (31) | 8 (25) | 14 (44) |

| Generation III | 5 (22) | 3 (13) | 15 (65) |

| H2b: Attack target ( = 53) | |||

| Human | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | 14 (56) |

| Machine | 8 (29) | 5 (18) | 15 (54) |

| H2c: Attack type ( = 53) | |||

| Opportunistic | 12 (32) | 9 (24) | 17 (45) |

| Targeted | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 12 (80) |

| . | Attack severity, (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Medium . | High . | |

| H2a: Crypto-ransomware type ( = 55) | |||

| Generation II | 10 (31) | 8 (25) | 14 (44) |

| Generation III | 5 (22) | 3 (13) | 15 (65) |

| H2b: Attack target ( = 53) | |||

| Human | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | 14 (56) |

| Machine | 8 (29) | 5 (18) | 15 (54) |

| H2c: Attack type ( = 53) | |||

| Opportunistic | 12 (32) | 9 (24) | 17 (45) |

| Targeted | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 12 (80) |

P < 0.1.

The degree of severity did not vary with the crypto-ransomware propagation class (i.e. Generation II vs. Generation III) n = 55, P = 0.334, nor with the attack target (i.e. human vs. machine), n = 53, P = 0.813.

The type of the attack (opportunistic vs. targeted) was also considered. Targeted attacks were more likely than opportunistic ones to lead to severe consequences, n = 53, P = 0.063. 80% of targeted attacks gave rise to impacts of high severity, whereas a considerably lower proportion of opportunistic attacks (45%) had high negative consequences. This difference is statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 177, P = 0.02) so we are inclined to accept Hypothesis 2b.

Post hoc, companies with a weak posture were much more likely to be targeted via machine vulnerabilities as a point of entry, whereas companies with medium or strong security postures were more likely to be attacked via social engineering tricks ( n = 34, P = 0.019). We also observed that 91% of targeted attacks were against organizations that had weak security posture. Table 7 demonstrates results of hypotheses tests.

Results of hypothesis tests

| Hypothesis . | Result . |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1a: An organization’s size influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 1b: An organization’s sector influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 1c: An organization’s security posture influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 2a: The crypto-ransomware propagation class influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 2b: The attack type, i.e. opportunistic or targeted, influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 2c: The attack target, i.e. human or machine, influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Rejected |

| Hypothesis . | Result . |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1a: An organization’s size influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 1b: An organization’s sector influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 1c: An organization’s security posture influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 2a: The crypto-ransomware propagation class influences the impact severity of a ransomware attack | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 2b: The attack type, i.e. opportunistic or targeted, influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Accepted |

| Hypothesis 2c: The attack target, i.e. human or machine, influences the degree of severity of a ransomware attack | Rejected |

| Attack ID . | Crypto-ransomware propagation class; attack target; attack type . | Organization alias . | Industry; size; sector . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | LawEnfJ | Law enforcement; SME; public |

| 2 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | GovSecJN | Government; large; public |

| 3 | Generation II; machine; opportunistic | GovSecJ | Government; large; public |

| 4 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | ||

| 5 | Generation II; machine; opportunistic | ||

| 6 | Generation II; machine; opportunistic | ||

| 7 | Generation II; machine; opportunistic | EducInstF | Education; large; public |

| 8 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | EducInstFB | Education; large; public |

| 9 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | LawEnfM | Law enforcement; SME; public |

| 10 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | ||

| 11 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | GovSecA | Government; large; public |

| 12 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | LawEnfJU | Law enforcement; SME; public |

| 13 | Generation III.b; machine; opportunistic | HealthSerJU | Health service; large; public |

| 14 | Generation III.a; human; targeted | ||

| 15 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | LawEnfF | Law enforcement; SME; public |

| 16 | Generation II; machine; opportunistic | ITOrgA | IT; SME; private |

| 17 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | ConstrSupA | Construction; SME; private |

| 18 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | EducOrgA | Education; SME; public |

| 19 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | SecOrgM | IT; SME; private |

| 20 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | ITOrgJL | IT; SME; private |

| 21 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | CloudProvJL | IT; SME; private |

| 22 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | InfOrgJL | Infrastructure; SME; private |

| 23 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | ConstrSupJ | Construction; SME; private |

| 24 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | RelOrgJ | Religion; SME; private |

| 25 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | SportClubJ | Entertainment; large; private |

| 26 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | UtilOrgD | Utilities; large; private |

| 27 | Generation III.a; e-mail; targeted | VirtOrgD | IT; SME; private |

| 28 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | CleanOrgD | Cleaning; SME; private |

| 29 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | EducOrgD | Education; SME; public |

| 30 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | SerOrgD | Waste; SME; private |

| 31 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | EducCompD | Education; SME; public |

| 32 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | PrimOrgD | Education; SME; public |

| 33 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | LogOrgD | Logistics; SME; private |

| 34 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | ITCompD | IT; SME; private |

| 35 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | LogWarJ | Logistics; large; private |

| 36 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | TranspOrgJ | Transport; large; private |

| 37 | Generation II; human; targeted | CharOrgJ | Charity; SME; public |

| 38 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | EducInstJ | Education; large; public |

| 39 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | DigMedM | Retailer; SME; private |

| 40 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | ConstrSupAP | Construction; SME; private |

| 41 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | FinOrgAP | Finance; SME; private |

| 42 | Generation II; unknown; unknown | ConstrOrgAP | Construction; SME; private |

| 43 | Generation II; unknown; unknown | LetAgenAP | Letting agency; SME; private |

| 44 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | EducOrgAP | Education; large; public |

| 45 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | ConstrArcAP | Construction; SME; private |

| 46 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | LegalOrgAP | Legal; SME; private |

| 47 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | BevOrgAP | Beverages; SME; private |

| 48 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | ChCarAP | Childcare; SME; public |

| 49 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | EducPrimAP | Education; large; public |

| 50 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | RetOrgAP | Retailer; large; private |

| 51 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | ||

| 52 | Generation III.a; machine; targeted | ITOrgAP | IT; SME; private |

| 53 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | MarkOrgAP | Marketing; SME; private |

| 54 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | ChemOrgAP | Chemical; SME; private |

| 55 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | EducHscAP | Education; large; public |

| 56 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | HospOrgAP | Hospitality; large; private |

| 57 | Generation II; human; opportunistic | WasteOrgAP | Waste; SME; private |

| 58 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | FinCompAP | Finance; large; private |

| 59 | Generation II; human; targeted | LegAdvAP | Legal; SME; private |

| 60 | Generation III.a; machine; opportunistic | LegSolcAP | Legal; SME; private |

| Questions . |

|---|

| Can you please tell me about the attack? |

| How would you rate the attack in terms of the level of severity? |

| Was your business affected by the ransomware attack? |

| If yes, then to what extent? |

| What functions were affected? |

| Were your data affected by the ransomware attack? |

| If yes, then to what extent? |

| Did you manage to restore the data that were encrypted? |

| In your opinion, are there any other negative impacts the ransomware attack had on your organization? |

| In your opinion, was the ransomware attack effective? |

| If yes, why do you think ransomware was effective? |

| What factors contributed to the effectiveness of this attack? |

| Crypto attacks . | Category . | Item → corresponding impact level → corresponding digit . |

|---|---|---|

| Attack 1 . | Business continuity disruption timeframe . | Up to 1 week → ‘Low’ → 1 . |

| Encrypted information critical to business . | Not critical → ‘Low’ → 1 . | |

| Information loss . | Some loss acceptable with incremental backups → ‘Low’ → 1 . | |

| Affected devices . | One desktop and shares on a server → ‘Low’ → 1 . | |

| Recovery time . | Up to 2 weeks → ‘Low’ → 1 . | |

| Maximum value | 1 | |

| Attack impact level | Low | |

| Attack 9 | Business continuity disruption timeframe | Up to 1 week → ‘Low’ → 1 |

| Encrypted information critical to business | Critical to high priority functions → ‘High’ → 3 | |

| Information loss | Some loss acceptable with incremental backups → ‘Low’ → 1 | |

| Affected devices | Several desktops and shares on servers → ‘Low’ → 1 | |

| Recovery time | Up to 1 month → ‘Medium’ → 2 | |

| Maximum value | 3 | |

| Attack impact level | High | |

Organization size does not matter, ransomware is indiscriminate

Within the observed sample, organization size, by itself, did not affect the severity of attacks. As outlined in ‘Organisation characteristics: size and sector’ section, prior findings and opinions on the relationship between organization size and the incidence of ransomware attacks are rather inconsistent, with some saying that ransomware is mainly a problem for large enterprises and others saying that SMEs make up the bulk of the victims. Of the organizations that we observed, SMEs and large organizations were similarly impacted by ransomware attacks and in most cases the impact felt was of high severity. This result is consistent with interpretations expressed by police officers from UK Cybercrime Units:

Ransomware is indiscriminate. It does not choose its victims. It chooses computers and those computers can be owned by anybody. (Detective Sergeant, CyberBL)

Ransomware does not target organisations of a particular size. All organisations, small, medium and large, are equally affected. (Detective Sergeant, CyberRM)

We observed several large organizations that experienced severe consequences of crypto-ransomware attacks (e.g. EducInstFB, GovSecA, HealthSerJU, SportClubJ, etc.) as well as SMEs (e.g. LawEnfJU, LawEnfF, ITOrgA, ConstrSupA, etc.). Therefore, regardless of how large or small an organization is, there is no room for complacency. SMEs often baulk at spending their limited funds on IT security measures, weighing things up on the basis of the financial cost of countermeasures vs. the expected probability and expected impact of an attack [ 30 ]. While we cannot offer any insights into the probability of an attack, we can speak about impact. Our findings show that if an organization has weak defence mechanisms, then regardless of whether it is an indigenous start-up or a large multi-national corporation, it is likely to experience very severe consequences in the event of a ransomware attack, such as having critical systems knocked out, heavy data losses and major disruptions of several weeks or more.

Private sector organizations are more likely to experience severe effects

Private sector organizations were more likely to report severe impacts than were those in the public sector in the sample observed in this study. This finding can be explained by the very nature of public organizations as compared to private businesses. Public sector organizations are generally state-owned with an obligation to provide some universal service such as healthcare, education, policing, or civic administration. The private sector, on the contrary, is mainly composed of organizations whose ultimate purpose is not to serve the public but to generate profit. Cyberattacks on profit-driven organizations normally lead to substantial financial losses, reputational damage and loss of customers; the series of security breaches on TalkTalk is one such example [ 47 ]. If public organizations such as councils, state agencies and police departments experience a cyberattack, they may lose public confidence, but as sole suppliers they are not going to lose customers or revenue as they are publicly funded. As an IT/Security Manager from GovSecJN (a public organization fully funded by the UK government) explained:

Yes, there was a financial impact because resources were directed towards dealing with the cyber-attack. But it is difficult for us to quantify the financial impact … . The impact is different for us. It is the impact on service delivery to public. How we care for children. How we care for adults. Even road potholes – people could not report potholes because our systems were down.

Information from interviews with police officers working in the UK Cybercrime Units confirmed our impression that private sector organizations suffer more severe consequences; e.g. a specialist detective within the CyberTL unit told us based on his extensive experience that:

Cybercriminals know that the private sector depends on customer service. They know that these organisations will pay. Especially, we find that a lot of IT companies have been hit. I do not think this is because IT companies are more prone to targeting. It is just because when they are hit by ransomware, it is so much more devastating for them due to their dependency on customers.

This observation is in line with our finding that 86% of respondents from the IT industry experienced attacks of high severity. However, it should be noted that our sample is based on attack victims only and is not representative of the number of potential organizations in each industry. Additionally, public or semi-public institutions may experience an equivalent attack as being less critical simply because they are not in competition with other providers.

Against the threat of ransomware, a vigilant security posture is vital

Our hypothesis that there is a relationship between organizational security posture and attack severity was supported. Most specifically, a weak security posture leads to a preponderance of very severe attacks. This suggests that the attacks were detected late, handled badly, or inadequately isolated. Although this observation is relevant to any type of cybercrime, successful ransomware attacks entail unique and rather devastating consequences such as disabled systems, encrypted data and, subsequently, halted business operations. A security weakness that could be easily fixed might cause substantial damage to the victim and even bankruptcy. For example, LogOrgD was infected via a server vulnerability that was widely documented by academics, security vendors and government bodies. Subsequently, the organization lost access to all critical data, including backups. The victim was rapidly losing its customer base and the business was close to bankruptcy. The business owner was particularly distressed and at some point, even had suicidal thoughts – a lifetime of hard work was about to turn into ashes. Ultimately, the company managed to survive but the recovery was timely, costly and extremely challenging. Therefore, IT/Security professionals must be extremely vigilant when it comes to protecting their organizations against ransomware. There is no simple technological ‘silver bullet’ that will wipe out the crypto-ransomware threat. Rather, a multi-layered approach is needed which consists of socio-technical measures, zealous front-line managers and active support from senior management [ 8 ]. As an IT/Security Manager from LawEnfJ puts it:

You have to have the fundamentals in place. If you are talking about backups after the event, you are dead in the water. You must have your system set up in a way that actively thwarts these attacks. If you are playing catch-up, then I am sorry, but the game is over at that point. You must stay up-to-date. If you are not staying current in the industry, you are going to get in trouble really quick.

Several respondents commented that if vulnerabilities are not closed down following ransomware attacks, organizations will get attacked again. For example, GovSecJ was attacked 4 times within 6 months. Although the IT/Security Manager wrote a report recommending organizational changes, senior management did not act upon it. Subsequently, three more attacks followed.

Though LawEnfM made a decision to implement all appropriate changes following the first ransomware attack, ransomware struck second time during the recovery process, taking advantage of the same vulnerabilities. Since the organization suffered considerably as a result of two consequent attacks, the external IT provider made a decision to pay the ransom as they felt responsible. Following this devastating experience (two attacks within 2 weeks), LawEnfM made several important changes in its approach to cybersecurity. HealthSerJU had to experience two very severe attacks before senior management realized the importance of security controls and measures:

I think both attacks fundamentally came down to the fact that there was an under-appreciation of the importance of IT and, therefore, the focus on ensuring that those systems were properly protected was not there … . If we wanted to take a positive from the attacks, it would be that finally executive management gave IT a profile that it has never had before. (IT/Security Manager, HealthSerJU)

Within our sample, public organizations had considerably stronger security postures than those in the private sector. Totally, 78% of the private organizations that we looked at had weak security postures, as opposed to 38% in the public sector. This may be because public institutions have a stronger regulatory mandate to have IT security policies in place. In the UK, the Cyber Essentials scheme was introduced in 2014 and is required for all central government contracts [ 48 ]. In contrast, in the private sector, the majority of organizations do not mandate their suppliers to have cybersecurity standards in operation [ 4 ].

Of course, the promotion of security standards is one matter, adoption is another and actual compliance yet another again. In the past 12 months, 17 452 Cyber Essentials certificates were issued by the UK government [ 49 ] which, going by the estimated 2.6 million businesses in the country [ 50 ] represents just 0.7% of the population. Within higher education institutions – from which division 29% of our public sector sample was drawn – there has been considerable resistance to the uptake of the Cyber Essentials standard [ 51 ]. The ISO27001 standard has been more widely adopted in the UK, but less so in public administration and educational organizations than elsewhere [ 52 ]. The annual UK Cyber Breaches Surveys of recent years reveal that a growing number of businesses are adopting Cyber Essentials, ISO27001, or other similar policies, but it still remains at about half who have no such measures in place [ 4 ].

Ransomware attacks, even of the less sophisticated type, can wreak havoc

There was no pronounced effect of the crypto-ransomware propagation class upon attack impact in the sample examined in this study. This is an interesting finding because Generation III crypto-ransomware has the ability to propagate across large networks and completely paralyse organizational operations. As a Detective Sergeant from CyberTR pointed out:

When I first started, the virus was very specific to the machine. The machine that clicked on the email was the machine that got the virus and the ransomware and that was it. More recent variants of ransomware have the ability to spread. There is definitely a distinction between ransomware that will hit a computer and encrypt any physically connected devices such as USBs, storage devices, and it is a lot more simple, and the likes of WannaCry that will travel across networks and spread to all computers. We have seen this evolution, where suspects are using vulnerabilities to spread across networks. This type of ransomware is more prevalent than it ever was because it gives hackers an advantage.

Rationally, Generation III should bring more devastation. However, our data show otherwise. For example, SecOrgM was infected with the less sophisticated Generation II crypto-ransomware. The victim declared bankruptcy shortly after the attack because the organization did not have backups, could not operate without hijacked data and at the same time was not able to meet ransom demands. Similarly, GovSecJN was hit with the Generation II ransomware class but it had a detrimental effect on the victim. Although GovSecJN recovered relatively quickly, data critical to high priority functions was encrypted, affecting essential functions of the organization. Such organizations provide vital services to the local community and many people depend on these services.

On the contrary, EducInstFB was attacked with Generation III crypto-ransomware that infected hundreds of devices. EducInstFB and its staff lost access to an enormous volume of data, which had scientific value. Several critical systems were disabled that stopped the victim from performing their normal daily tasks. The management made a decision to pay the ransom. Although the recovery was lengthy and challenging, EducInstFB eventually repaired its systems and recovered the majority of data. Another victim of Generation III crypto-ransomware – HealthSerJU – was attacked twice and on both occasions over a thousand devices were infected. Although these attacks had a significant negative effect on the delivery of services, HealthSerJU had effective backups and, therefore, promptly restored its systems. EducOrgA was also infected with Generation III crypto-ransomware, affecting the whole network. However, due to the nature of its business, EducOrgA continued its work as a primary school and teaching activities were not interrupted (while administrative data were gradually restored).

Following these observations, we concluded that the crypto-ransomware propagation class alone may not have a direct impact on the consequences of these attacks. Rather, a combination of factors (e.g. the nature of business, availability of resources to recover data or pay the ransom, the type of systems affected, level of preparedness, etc.) are at play.

Beware the ‘weakest link’

Although Hypothesis 2c was rejected, indicating that the severity of a ransomware attack is not influenced by the attack target (i.e. human or machine), we observed that organizations with a weak posture were much more likely to be targeted via machine vulnerabilities as a point of entry, whereas those with medium or strong security postures were more likely to be attacked via social engineering tricks. This finding could be explained by the fact that many of our study participants trust that technical controls provide an adequate defence against cyberthreats, which is also a commonly accepted belief among industry professionals. Consequently, IT/Security professionals focus on implementing measures like e-mail hygiene, vulnerability and upgrade management and sophisticated monitoring and detection systems, but seemed to neglect the ‘human factor’ problem and do not have strong security education and training, the importance of which as a security countermeasure is well established [ 6 , 37 , 38 ]. Therefore, these organizations are attacked via ‘the weakest link’ – they may have an adequate defence from a technical perspective, but weak employee security practices. As the IT/Security Manager from GovSecJ put it:

Effective defence always starts with a user. You need to make sure that along with teaching people how to use your applications, IT systems, you incorporate in there a good amount of cyber security.